Job 1-2; 13; 19; 27; 42

The first thing that caught my attention when I looked at the Sunday School study guide for this lesson on Job was that the prescribed lesson plan jumps around the book of Job, skipping many chapters in between. This is, I’m sure, par for Sunday School study of Job as we obviously can’t cover 42 chapters in any detail in one lesson. But I wonder if most of us are even aware that there are so many chapters in this book. Whatever could the story be on about for so long? I was curious as to why these chapters were chosen while so many others were skipped. Of course the main reason why these chapters were chosen is because they have the most significant theological content, but also, I believe, because they are some of the more upbeat chapters, and the ones that move the narrative along. I’ll go into what I mean by that more in a moment.

I’d like to discuss some of the background information of the book of Job. As you may have noticed from the title of the post, Job is generally categorized by scholars as part of the same genre of Wisdom literature that we discussed last week with the books of Proverbs and Ecclesiastes. The overall style and purpose of the book of Job can be compared to these other examples of the genre, but you will notice one major difference: Job reads much more like a narrative story than do the other two — at least the beginning and conclusion of the book are set up in narrative style. However, generally speaking, the middle chapters are poetic dialogues that are more in line with Proverbs and, especially, Ecclesiastes. The Job of these dialogues doesn’t seem as heroic or optimistic as the Job in the opening and closing narratives. My hunch is that this is one of the main reasons why the lesson plan doesn’t cover much of this “middle” material. Whereas the book of Proverbs contains mostly positive, encouraging advice, the dialogues that run through the middle of Job are much more pessimistic — more similar to the style of Ecclesiastes. John J. Collins expounds on this disparity.

The Book of Proverbs represents “normal” wisdom in ancient Israel. It has much in common with the instructional literature of the ancient Near East, and it is characterized by a positive view of the world and confidence in its order and justice. This worldview was open to criticism, however, and already in antiquity some scribes found the traditional claims of wisdom problematic. The Wisdom tradition gave rise to two great works that questioned the assumptions on which the world of Proverbs was built. These works are the books of Job and Qoheleth (Ecclesiastes).1

But what does he mean by Job questioning the wisdom tradition as found in Proverbs? Well, in Proverbs the idea is that if you do the right thing, you will be blessed. If you keep the commandments, then God will cause you to prosper. Job, however, addresses the question of why the righteous sometimes suffer while the wicked seem to prosper. This is an age-old question that is difficult to answer. It is up to you to decide whether the book of Job answers this question, but we do see in the narrative that Job does (not, however, without some degree of moaning and complaining) endure his trials faithfully, and is blessed abundantly by the Lord.

Just to add a few more details of the book’s background, we should note that we don’t know when or by whom this book was written. There is no indication in the story as to who the author was, but some tractates of the Talmud indicate that the book was thought to have been written by Moses. Some Rabbinic sources claim that Job lived before Moses and that Moses found the story of Job in an ancient Semitic tongue and translated it into Hebrew. There are a number of expressions in the book which lead some to believe that it is quite ancient. For example, the mention of the “sons of God” that gather together for the heavenly council (Job 1:6) is an early belief that is later usually replaced by reference to “angels” rather than “sons”. This feature could, but not necessarily, place the book before the Babylonian exile. The fact that Job offers sacrifice is taken by some to indicate that the story is meant to be set in pre-Mosaic times, but this is not necessarily the case as the Bible depicts many post-Mosaic figures, including Israel’s kings, as offering legitimate sacrifices (note: it is possible that the story is meant to take place in patriarchal times, but need not have been written then). The reference in that same verse to Satan (Heb. “the Satan” = the adversary, the accuser), and the role that he plays in the story, is considered by many scholars to indicate that the text is post-exilic. In general, the modern scholarly opinion is that the book was likely written around the 5th century B.C., after the book of Proverbs and before the book of Ecclesiastes. Notwithstanding the date that it may have finally been written down, Job preserves an ancient theology that is similar in many ways to much of the material in the Psalms, Isaiah, and other pre-exilic writings.

Again, it is difficult to know who wrote the book and whether or not it is purely a work of fiction — a parable. However, the New Testament (James 5:11) speaks of Job as if he were real enough and in the Doctrine and Covenants (D&C 121:10), the Lord himself refers to the suffering of Job. Also, significantly, Job is mentioned in Ezekiel 14:14 as one of three great men who had ministered to the house of Israel.

On to the content of the book…

The lesson study guide lays out the content of the chosen passages thus:

- a. Job 1–2. Job experiences severe trials. He remains faithful to the Lord despite losing his possessions, children, and health.

- b. Job 13:13–16; 19:23–27. Job finds strength in trusting the Lord and in his testimony of the Savior.

- c. Job 27:2–6. Job finds strength in his personal righteousness and integrity.

- d. Job 42:10–17. After Job has faithfully endured his trials, the Lord blesses him.

The Introduction (chapters 1-2)

The narrative begins by presenting Job as a very blessed man. He lived in the land of Uz (somewhere in the “east”) and was the richest guy around. He had ten children and an absolutely incredible number of sheep, camels, oxen, donkeys, and numerous servants to take care of them. We are told that he was a perfect and upright man, one that feared God and eschewed evil. We are probably meant to assume that this is why he was so abundantly blessed.

However, Job’s luck changes when the Adversary makes his way into the Divine Council to fulfill his role as “prosecuting attorney”. Satan stands before Jehovah and informs him that he has been going to and fro and up and down the earth — likely just looking for someone to accuse of something, because that’s his job. The Lord presents Job as a perfect and upright man unlike any other on the face of the earth. Satan is quick to argue that this piety is only due to how blessed and protected he has been of God and that if the Lord took it all away, Job would immediately “curse thee to thy face” (Job 1:11). The Lord agrees to let Satan try Job’s faithfulness by permitting him to have power over all of Job’s possessions.

In rapid succession, all of Job’s belongings, including his ten children, are totally destroyed. Job is left with nothing! However, he did not react by cursing God as Satan had predicted. Despite his great sorrow at the loss, he worshiped God and said:

(Job 1:21) Naked came I out of my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return thither: the LORD gave, and the LORD hath taken away; blessed be the name of the LORD.

Satan, not wanting to be proven wrong, comes to the next council meeting, where the Lord announces to him that Job “still … holdeth fast his integrity, although thou movedst me against him, to destroy him without cause” (Job 2:3). But Satan pushed further, declaring that if the Lord would inflict Job’s own body, his personal health, then Job would curse him to his face. The Lord agrees to allow this further test of Job’s loyalty, but advising Satan to spare Job’s life.

Job is then tortured with painful boils and sores that covered the entirety of his body. His suffering is unbearable, to the point that his wife recommends that he “curse God and die.”

(Job 2:10) But he said unto her, Thou speakest as one of the foolish (as opposed to wise) women speaketh. What? shall we receive good at the hand of God, and shall we not receive evil? In all this did not Job sin with his lips.

It is important to remember that although we know of the deal between the Lord and Satan, Job has no idea why he is being put through all this. This is what makes his endurance so significant — he has always been a righteous man and has always been blessed for it — he has no reason to expect these trials that would normally expected to be God’s punishment for the wicked.

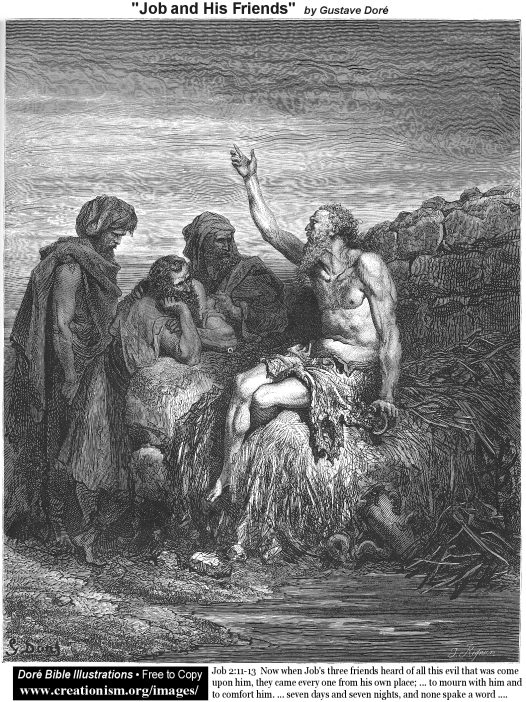

Three men, who are supposed to be his friends — Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar — come to comfort him, but end up just rubbing it in. Their assumption is the traditional expectation that the righteous will always be blessed, and if you are suffering it must be because you have sinned. As the story proceeds, they try to pressure Job into confessing his sins which obviously brought on this great suffering. Job, however, maintains his innocence. The lesson plan, however, does not cover these intermediary chapters, likely because Job really begins complaining about his situation, cursing the day he was born and wondering why God has decided to become his enemy. While there are certainly some interesting philosophical discussions in these sections, some might say that they are not especially inspiring or faith-promoting.

Just a note on these three friends — Eliphaz the Temanite, Bildad the Shuhite and Zophar the Naamathite. You may notice that their genealogy — their family name– is always mentioned with their given name, while we are not told from what family Job comes from. Why is this? Looking into the geneaolgies of these three friends, we can conclude that all three are meant to be descendents of Abraham. Some traditions held that the three friends were three kings. They also seem to have the right and authority, likely due to their relation to Abraham, to offer sacrifice (see Job 42:8, although it is difficult to know if it is they who are to make the offerings or if it is Job). We do not know that Job was not of Abrahamic heritage, but the emphasis on the Abrahamic families of the friends is likely deliberate — they represent a pious lineage and thus are in danger of falling into the holier-than-thou, hypocritical attitude that is characteristic of the Pharisees in the New Testament. We see that in the end of the story, although they assumed superiority over Job, he is the one who is, contrary to their expectations, finally accepted. When they bring their burnt offerings, it is Job that is to offer an intercessory prayer on their behalf.

Chapters 13, 19

Job notes, in chapter 13, that in all their accusations against him, the three friends have presumed to speak for God. They have been trying to insist that God is just and would not cause suffering to come upon a righteous man. But Job accuses them of speaking “deceitfully” for God (Job 13:7–8) by maintaining that God would always preserve the obedient from harm, implying that Job must be a sinner. Job predicts that God will, in the end, rebuke them for this approach. I don’t think that Job sees God as malevolent, but Job is willing to be faithful to God no matter what He decides to do. He declares, in verse 15, “Though he slay me, yet will I trust in him” and continues to assert that he knows that God will be his salvation. He then says, and this is likely a jab at his friends, that hypocrites shall not come before God. We see here in Job a faith that includes trusting in God although we may not know his purposes.

Chapter 19 presents a similar theme. Although his friends have turned against him, and it appears that even God has turned against him, he still maintains his faith. Although he does not understand why God is doing this to him, he knows that he must remain faithful through it all in the hope that one day he will be redeemed from this suffering and enjoy the glorious presence of God. He declares in the famous passage:

25 For I know that my redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth:

26 And though after my skin worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God:

27 Whom I shall see for myself, and mine eyes shall behold, and not another; though my reins be consumed within me.

Although many biblical scholars attempt to dismiss such notions, these verses attest to a belief in a divine redeemer who would come from heaven to earth at some future time (see also Job 9:33; 16:19; 33:23). It also demonstrates that Job believed that he would see God with his own eyes, apparently at some point after his death. We should take phrases such as ”yet in my flesh” and “mine own eyes shall behold, and not another” to be references to a belief in a future bodily resurrection (although this topic is very much debated and many scholars likewise do not accept this interpretation). It is the hope in this future redemption that permits Job to maintain his famous patience.

Chapter 27

Because of his hope of future redemption, Job sees great value in continued obedience to God, although he believes that it is God who is willingly afflicting him at present. Although he doesn’t understand why God is doing this, he recognizes God’s sovereignty and the importance of keeping his commandments and living righteously. He declares:

4 My lips shall not speak wickedness, nor my tongue utter deceit.

5 God forbid that I should justify you: till I die I will not remove mine integrity from me.

6 My righteousness I hold fast, and will not let it go: my heart shall not reproach me so long as I live.

Job knows that although the righteous are not always spared suffering and pain, the wicked have no hope whatsoever. Because of their evil ways, their soul will not be saved at the last day; God will not hear their cries in their time of need. Those who possess wisdom know that they must fear/obey God.

Conclusion (Chapter 42)

Before commenting on the epilogue to this story — the happy ending — I want to touch on how we got there. Throughout the book, we have Job being in the dark as to why God is apparently punishing him (he doesn’t realize that this is all just a test of his faith), and we have his “pious” friends basically persecuting him, telling him that he must be a sinner because God doesn’t afflict the righteous. The reality, in the story, is that none of them understand God’s purposes. The friends were mistaken in that they assumed that God would never allow evil to come upon good people. Job was wrong to think that God was punishing him for no reason or that God had become his enemy. It is the fourth visitor, Elihu (ch. 34 — note the similarity in name to Elijah), who makes this clear. Although he, too, seems to think that Job is in the wrong, it is what Job has thought and said rather than what he has done. Job has failed to understand that God is not unjust — that God does not err in his judgments or deliberately deal wickedly with mankind. Elihu informs Job that he has “spoken without knowledge, and his words were without wisdom” (Job 34:35); he did “open his mouth in vain; he multiplieth words without knowledge” (Job 35:16). Job failed to understand how God does things.

At the end of chapter 37, Elihu emphasizes Job’s lack of understanding of divine things be positing a series of questions regarding “the wondrous works of God” that are simply unfathomable to human beings. The ways of God are mysterious and beyond man’s comprehension.

As if to testify of the correctness of Elihu’s approach here, in chapter 38 the Lord himself appears to Job in a whirlwind and continues Elihu’s line of questioning. He asks many questions that He, God, would know, but that Job, the human would not (at least would not remember). Where was Job when the Lord laid the foundations of the earth, measured it and stretched the line upon it (masonry talk), and when the morning stars/sons of God sang and shouted for joy (the Creation imagery of these chapters deserves a post of its own). He goes on to question Job regarding the secrets of governing the heavens and the earth, secrets that only God would know. He demonstrates God’s great power in having created the greath behemoth and leviathan — beasts that can only be subdued by Jehovah himself. He asks Job (ch. 40):

8 Wilt thou also disannul my judgment? wilt thou condemn me, that thou mayest be righteous?

9 Hast thou an arm like God? or canst thou thunder with a voice like him?

Job had strived this whole time to maintain his innocence, assuming that his suffering must have been due to God being in the wrong. Job was still faithful to God, but he had misjudged God’s character. He thought that he knew better and that his own judgment was superior to God’s. But God clearly demonstrates to Job that man is nothing, that he understands nothing, especially not the purposes of God.

In the end, God proves that He is just and merciful to the righteous. When Job recognizes his inferiority to God’s power and knowledge, and that he had misunderstood God’s ways, he quickly repents of the error in his thinking and for the incorrect things he said about God. The Lord forgives him promptly and appears to him. Job’s faith becames full knowledge as he sees the Lord, announcing: (Job 42:5) “I have heard of thee by the hearing of the ear: but now mine eye seeth thee.” The three friends, who also thought they knew God’s will and ways, are then chastized by the Lord, because “ye have not spoken of me the thing that is right, as my servant Job hath” (Job 42:7). Because of their unworthiness in comparison to Job, God appoints Job as their intecessor between Him and them. Job’s prayers on their behalf are acceptable to God. Job is subsequently blessed with twice as much as he previously had.

The lesson that I feel is to be learned from the book of Job is that we simply do not know God’s purposes. Our duty is to remain faithful to him and endure to the end with patience. Look at Joseph Smith, who was compared to Job by the Lord, and all that he suffered through in his life. He was a righteous prophet of the Lord, yet he had to go through so many difficult and terrible things — the suffering never seemed to end. Do we ever think of that? Do we question why God would put him through all that? And why did God let someone close to me die? And why do these terrible things always happen to me? The story of Job illustrates that we simply do not know what God’s purposes are for us. Does God hate us or simply ignore us? Is God responsible for all the evil in the world? We must admit that we simply do not understand God’s ways or what he plans for our lives. We must simply trust in Him and have hope for that future redemption when we will be saved from all pain and sorrow and will be able to see God with our own eyes, in our own glorified flesh, and be able to abide in his loving presence. God loves us and knows what’s best for us. He promises that if we are faithful, we will return to Him in his Kingdom. He didn’t say that there would be no pain, but that there could be a bright, happy ending with blessings more abundant than we could ever imagine — but for now we must have the patience of Job.

- John J. Collins, Introduction to the Hebrew Bible (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004), 505

Continue reading at the original source →