The Know

Beginning with the pioneering work of Hugh Nibley,1 scholars have noticed that the Book of Mormon contains what are called colophons (from the Greek word kolofōn, meaning “summit,” “top,” or “finishing”). “In antiquity,” one scholar explained, “the beginning and/or the end of a literary text was often marked by colophons. The colophons as superscriptions and subscriptions contained various information about the published text (addressee, author, scribe, subject, chronological information, etc.).”2 Nephi’s introductory colophon is arguably the most notable example of its use in the Book of Mormon. After summarizing the contents of his record and identifying himself as both scribe and author of the text, Nephi began his account by affirming: (1) his good parentage and upbringing, (2) his education and scribal training, and (3) his reliability as an author (1 Nephi 1:1–3).

But Nephi was not the only Book of Mormon author to use colophons. Enos (Enos 1:1–2) and Mormon (Mormon 1:1) both begin their accounts with a colophon, while Jacob (Jacob 7:27) included a colophon at the conclusion of his record. Mormon also used colophons throughout his abridgement in order to introduce verbatim or near-verbatim quotations of various source texts.

Alma 5, for example, is prefaced with this introductory colophon: “The words which Alma, the High Priest according to the holy order of God, delivered to the people in their cities and villages throughout the land.” Likewise, Samuel the Lamanite’s prophecies to the Nephites recorded in Helaman 7–16 are introduced with a simple colophon identifying the author behind the text (Samuel) and a short summary of its contents.3

The use of colophons to signal the beginning or end of a text is widely found in biblical, Egyptian, and Mesopotamian sources. The prophetic books of the Bible often begin with colophons which identify the prophet and briefly introduce the historical setting in which he was prophesying. For instance, the book of Isaiah begins: “The vision of Isaiah the son of Amoz, which he saw concerning Judah and Jerusalem in the days of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, kings of Judah” (Isaiah 1:1).4

Sometimes biblical colophons describe the prophecies as coming literally “by the hand” (bĕ yad) of the prophet (cf. Malachi 1:1; Haggai 1:1), a feature shared in Mesopotamian texts to identify the copyist (“by the hand of so-and-so”) and in later Egyptian texts to indicate authorship (“written by his own hand”; cf. 1 Nephi 1:3).5

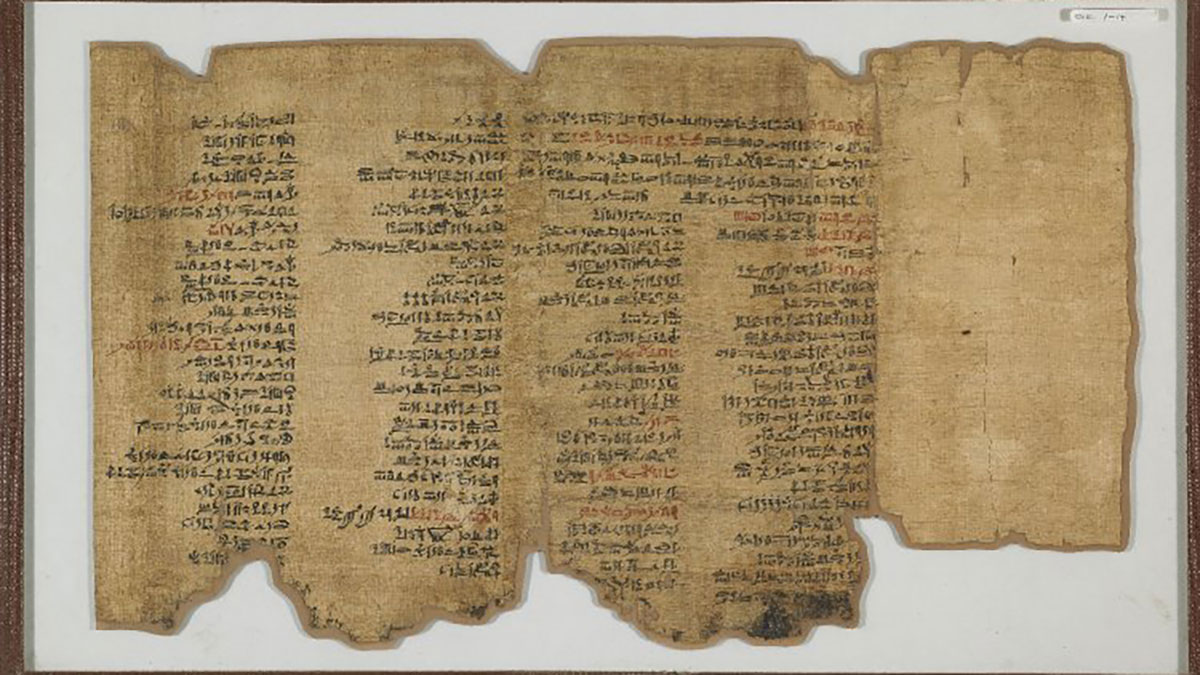

As Nibley recognized, Nephi’s colophon at the beginning of his account shares striking similarities to the colophon found in an ancient Egyptian manuscript called the Bremner-Rhind Papyrus.6 Further similarities with Egyptian texts could be cited. Indeed, Egyptian literary texts very often end in either a short, formulaic colophon certifying that the text has been copied correctly or a longer colophon which also includes the identity of the scribe.7 Introductory prefaces to Egyptian literary texts likewise often include the name and titles of the writer or subject of the narrative.8 These and other considerations led Nibley to conclude that the type of colophon seen in 1 Nephi 1:1–3 is “highly characteristic of Egyptian compositions.”9

The Why

Nephi said he wrote his record “in the language of [his] father, which consists of the learning of the Jews and the language of the Egyptians” (1 Nephi 1:2). This being the case, it is reasonable to expect that his writings should bear the marks of an ancient Judeo-Egyptian literary culture. Nephi’s use of colophons fulfills this expectation remarkably well. Inasmuch as there is clear evidence (unavailable in Joseph Smith’s day) for Egyptian influence on Jewish literary and scribal culture before and during Nephi’s time,10 this in turn reinforces the book’s historicity.

Besides this, learning to recognize colophons may assist readers in making sense of the Book of Mormon’s complex narratives. This is because colophons were used at strategic points in the text to help readers identify when certain sources are being cited, or when authorial voices are shifting from one to another (such as Mormon’s to Alma’s in Alma 5). As explained by LDS scholar John A. Tvedtnes, colophons “provide valuable clues to the process of writing and compiling the [Book of Mormon].”11

The presence of colophons in the Book of Mormon forcefully testifies of the “great efforts made by its writers and editors to make the record as clear as possible.”12 As one whose soul “delight[ed] in plainness” (2 Nephi 25:4), it’s completely understandable, then, why Nephi would use colophons in his record, and why his prophetic and scribal descendants would follow suit.

Further Reading

Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert/The World of the Jaredites/There Were Jaredites (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 17–19.

John A. Tvedtnes, “Colophons in the Book of Mormon,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1991), 32–37.

John A. Tvedtnes, “Colophons in the Book of Mormon,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 13–16.

Thomas W. Mackay, “Mormon as Editor: A Study of Colophons, Headers, and Source Indicators,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2, no. 2 (1993): 90–109.

John A. Tvedtnes and David E. Bokovoy, “Colophons and Superscripts,” in Testaments: Links Between the Book of Mormon and the Hebrew Bible (Toelle, UT: Heritage Press, 2003), 107–116.

- 1. Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert/The World of the Jaredites/There Were Jaredites (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 17–19.

- 2. Csaba Barlogh, The Stele of YHWH in Egypt: The Prophecies of Isaiah 18–20 concerning Egypt and Kush (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 69. Compare this definition with that of Leila Avrin, Scribes, Script, and Books: The Book Arts from Antiquity to the Renaissance (Chicago and London: American Library Association and The British Library, 1991), 79. “The tradition of the colophon . . . flourished in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. The colophon’s information and composition varied. It gave the standard title, that is, the book’s opening words, and the name of the scribe, at times with his patronym. Seldom was the book’s author named. Sometimes the colophon verified that this edition was a true copy of the original book, giving the name of the scribe of the prototype and its date and owner. Then the date of the copy would be given along with the name of the patron who commissioned the book and the nature of the work.”

- 3. See these and other examples identified by John A. Tvedtnes, “Colophons in the Book of Mormon,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1991), 32–37; “Colophons in the Book of Mormon,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 13–17; Thomas W. Mackay, “Mormon as Editor: A Study of Colophons, Headers, and Source Indicators,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2, no. 2 (1993): 90–109; John A. Tvedtnes and David E. Bokovoy, “Colophons and Superscripts,” in Testaments: Links Between the Book of Mormon and the Hebrew Bible (Toelle, UT: Heritage Press, 2003), 107–116.

- 4. See also Jeremiah 1:1–3; Amos 1:1; Micah 1:1; Zephaniah 1:1.

- 5. Karel van der Toorn, Scribal Culture and the Making of the Hebrew Bible (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 32; John Gee, “Were Egyptian Texts Divinely Written?” in Proceedings of the Ninth International Congress of Egyptologists, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 150 (Leuvens: Peeters, 2007), 1:809. On biblical colophons generally, see H. M. I. Gervaryahu, “Biblical Colophons: A Source for the ‘Biography’ of Authors, Texts and Books,” in Congress Volume Edinburgh, VTSup 28 (Leiden: Brill, 1975), 42–59; D. W. Baker, “Biblical Colophons: Gevaryahu and Beyond,” in Studies in the Succession Narrative: OTWSA 27 (1984) and OTWSA 28 (1985), ed. W. C. van Wyk (Pretoria: OTWSA, 1986), 29–61; Michael Fishbane, “Biblical Colophons, Textual Criticism and Legal Analogies,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 42, no. 4 (1980): 438–449; Tvedtnes and Bokovoy, “Colophons and Superscripts,” 109–114.

- 6. Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, 17. The authority cited by Nibley (Raymond O. Faulkner, “The Bremner-Rhind Papyrus,” JEA 23 [1937]: 10) indicates that, “strictly speaking,” calling the opening of the text a colophon in this case is a “misnomer” since the colophon itself appears to be a later addition to the manuscript and is not an original composition. Nevertheless, Faulkner does allow for it to be called a “colophon” in a broad sense. Compare Faulkner’s views with those of Mark Smith, who sees no impropriety in calling the concluding lines of the manuscript a colophon even though the they were added after the rest of the text. See Mark Smith, Traversing Eternity: Texts for the Afterlife from Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2009), 120–121.

- 7. The most common formulaic colophon reads that the text “is finished from its beginning to its end as found in writing,” or simply “it is finished.” In P. Leningrad 1115 (the Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor) the colophon includes the name of the scribe: “it is finished from its beginning to its end as found in writing. The scribe, excellent in his fingers, Imeni, son of Imena.” See the examples collected and discussed in Michela Luiselli, “The Colophons as an Indication of the Attitudes Towards the Literary Tradition in Egypt and Mesopotamia,” in Basel Egyptology Prize 1: Junior Research in Egyptian History, Archaeology, and Philology, ed. Susanne Bickel and Antonio Loprieno (Basel: Schwabe & Co., 2003), 346–347.

- 8. Thus the opening lines of the venerable Story of Sinuhe. “The hereditary noble and commander, warden and district officer of the estates of the sovereign in the lands of the Asiatics, this truly beloved royal acquaintance, the follower Sinuhe, said: I was a follower who followed his lord, a servant of the king’s harem and of the hereditary princess, greatest of praise, wife of [King] Senwosret in Khnumet-sut and daughter of [King] Amenemhet in Ka-nofru, Nofru, the possessor of an honored state.” William K. Simpson, “The Story of Sinuhe,” in The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry, ed. William Kelly Simpson, 3rd ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 55.

- 9. Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, 17.

- 10. See generally Adolf Erman, “Eine ägyptische Quelle der »Sprüche Salomos«,” Sitzungsberichte der preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 15 (1924): 86–93; D. C. Simpson, “The Hebrew Book of Proverbs and the Teachings of Amenophis,” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 12, no. 3/4 (Oct. 1926): 232–239; Ronald J. Williams, “Some Egyptianisms in the Old Testament,” in Studies in Honor of John A. Wilson, ed. E. B. Hauser, Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 35 (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1969), 93–98; “‘A People Come Out of Egypt’: An Egyptologist looks at the Old Testament,” in Congress Volume Edinburgh, 231–252; Glendon E. Bryce, A Legacy of Wisdom: The Egyptian Contribution to the Wisdom of Israel (Lewisburg: Bucknell University, 1979). Orly Goldwasser, “An Egyptian Scribe from Lachish and the Hieratic Tradition of the Hebrew Kingdoms,” Tel Aviv 18 (1991): 248–253; David Calabro, “The Hieratic Scribal Tradition in Preexilic Judah,” in Evolving Egypt: Innovation, Appropriation, and Reinterpretation in Ancient Egypt, BAR International Series 2397, ed. Kerry Muhlestein and John Gee (Oxford, Eng.: Archaeopress, 2012), 77–85. On Nephi’s scribal training in general, including his use of Egyptian, see Brant A. Gardner, “Nephi as Scribe,” Mormon Studies Review 23, no. 1 (2011): 45–55.

- 11. John A. Tvedtnes, “Colophons in the Book of Mormon,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon, 37. What’s more, “the large number of these statements in such intricate relations both with each other and in the overall structure of the book teach us something else. They make it obvious that they came from ancient writers, not from Joseph Smith.”

- 12. Tvedtnes, “Colophons in the Book of Mormon,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon, 16.

Continue reading at the original source →