Our Dalton turned 16 last week.

Like some of his former birthdays, this one could have been given short shrift, being squished, as it is, between Christmas, our wedding anniversary, and New Year’s.

But this was The Big 1-6, and for months Dalton had been counting down the days. So we promised we’d really mark it this time. We’d holler to the heavens for joy at the marvel of our son’s life. We’d dance and sing and generally jubilate about life.

Vividly.

How?

Well, for starters, we’d invite the whole tribe.

Literally.

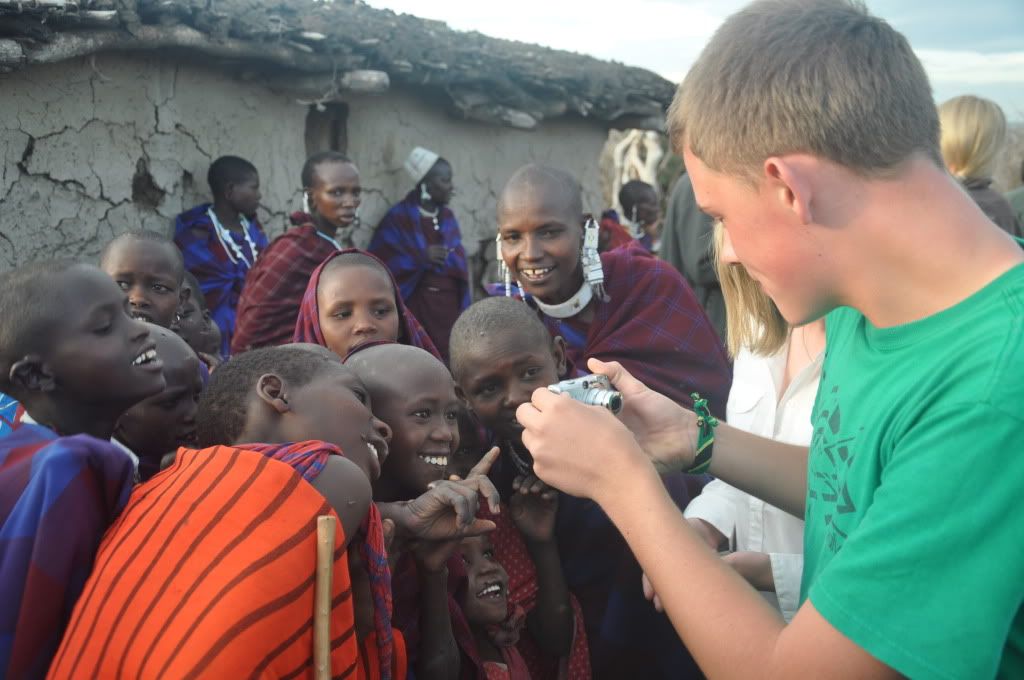

This is Dalton with some of his party guests, members of the Maasai tribe of Tanzania.

**************************************

We happened upon their boma (“boma”: Maa language for community/settlement), which lies between the Ngorongoro Crater (a 2,000 ft deep, 100 sq. mile large caldera—a virtual petri dish of African wildlife) and the borders of the Serengeti.

Oh, all right. We didn’t just “happen” upon Africa. In truth, we’d planned this trip to Tanzania specifically to pick up Claire, our daughter, who had just finished her fall internship as an assistant in a juvenile detention center in Moshi, near the Kenyan border.

While there, Claire fell fiercely in love with the people and their corner of the earth which science calls “The Cradle of Humankind”. It was from here, we learned, that mankind is to have sprung; the earliest signs of human life, in fact—dating to 3.7 million years ago—have been discovered and preserved within miles of where our very safari tents were pitched. Spending our son’s birthday (not to mention the birthday of the Son of God) in the “The Cradle of Humankind” felt significant to me, and in more than just a nice ‘n’ tidy poetic kind of way.

But you see I’m already getting ahead of the story.

Let’s get back to the boma. . .

Late in the afternoon of the eve of Dalton’s 16th, we and our travel friends were invited by Masenga Lukeine, a bilingual Maasai guide, to visit a local boma and interview its inhabitants. The Maasai, as you may already know, are a dominant tribe indigenous to eastern Africa. Nomadic pastoralists, the Maasai populate sizable swaths of Kenya and Tanzania where they herd cattle, (which they consider both sacred and theirs by divine right), sheep and goats, subsisting almost exclusively on their meat, milk and blood. For centuries, they’ve lived in polygamous clans governed by strict patriarchal rule, which weaves a tight fabric of social stratification. As a result, the boma is a formidably fortressed refuge from modernity.

It’s also fantastic stuff for a photo essay.

When our Jeeps approached the thorny thistle hedge boundary of this particular boma of a dozen or so huts, the first to greet us was this senior chief, followed by men from all six ranks of elders including the young spear-carrying warriors.

These Maasai had never had western visitors like us: odd, creamy-fleshed androids with light eyes and blonde hair, fitted pants with zips and buttons, and bulky digital cameras slung around our necks like strange black calabashes. Trailing Masenga, we came face-to-face with about four-dozen Maasai, all draped in brilliant reds and blues, their distinguishing tribal colors. I smelled farm. I saw the stretched earlobes, the yellowed eyes, the perfectly round heads, and everywhere in adults the two missing bottom teeth. (Removed in a childhood “maturation” ceremony. With a single jab of a blade. Without anesthetic. Or tears.) And though everyone was swatting flies from their faces, (everyone, that is, but the children, who seemed inured to them), I felt their regal bearing, their dignity.

I’d done my research, of course. Their polygamy? Because of my Mormon pioneer heritage, I remotely comprehended it. But their resistance to educating their girls? I growled inside. And their bloody rites of passage, especially the cruel (and continuing and incomprehensible) enforcement of female circumcision performed, in many cases, in early childhood? My very bones groaned. Could these people see the indignation I was trying to hide behind my eyes? Could they see my reprehension, my judgment, my sorrow, my seething? And as important, could I see anything in their eyes but all that essential yet messy cultural packaging? Could I see into those eyes, past the unpalatable facts? Most importantly, could I, if only for a moment, see with their eyes into their world, into my world?

Old women. I eyed them. Young wives. I tightened my aperture. Several younger soon-to-be brides toting other mothers’ and sisters’ and aunts’ toddlers on their hips. I searched their faces, adjusted my focus, zeroed in on what lay behind their eyes. There, I thought I saw pluck, intensity, wisdom. And loads of light.

And beauty.

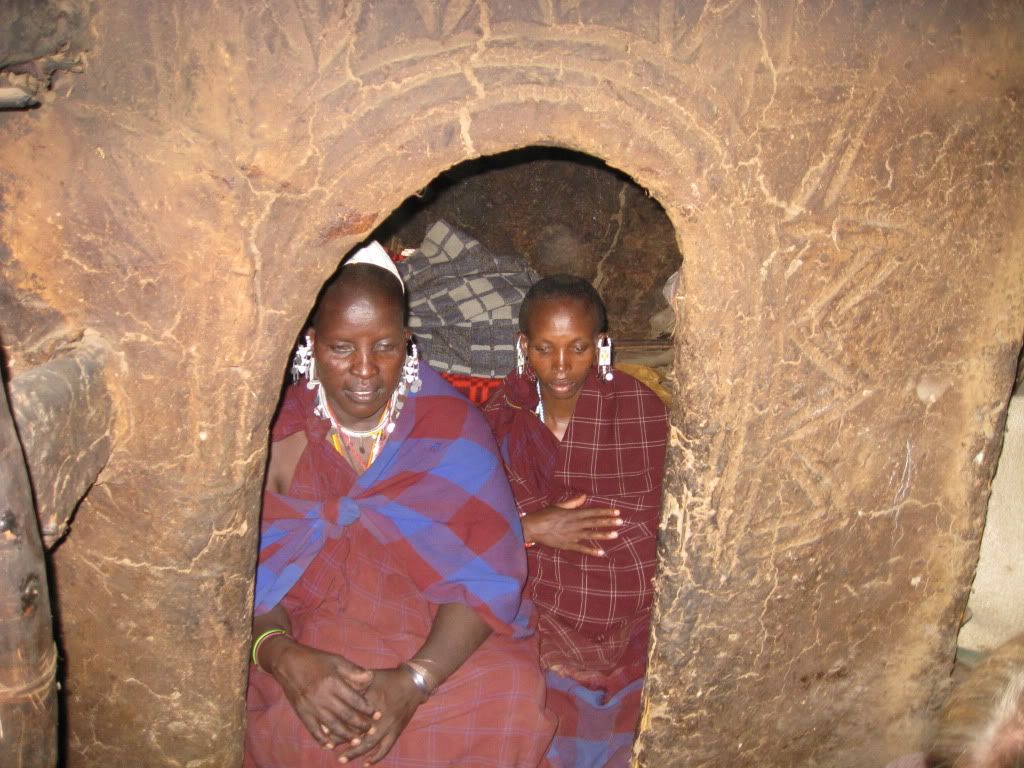

And darkness. At least when I entered one of their huts. There, I found lightlessness so complete, it froze me. Once I’d crouched through the 4-foot entrance and had gotten past the acrid sting of walls made of cow-dung plaster and the realization of live-in farm animals, (I nearly tripped over a goat then bumped into a sickly calf), I brailled my way to a corner. There, I squatted and, reaching to position myself, realized it wasn’t a knob of wood I was clenching, but someone’s knee. It was the younger of two women huddled beneath an archway, and with the light of my cell phone, I made out an older woman in a checkered robe. Next to her, a younger woman (the second wife, I was told), waited, holding the older wife’s newborn infant under her robes. She would stay at the delivered wife’s side for three consecutive months of rest and confinement. I instinctively reached to stroke both wives’ shoulders and pat the round of the very small baby’s back. The significance of the moment wasn’t lost on me, or on Dalton, who bent to me, whispering, “Is this anything like a Biblical manger?”

These women, I was taught, were the sole architects and engineers of their personal huts. Twelve huts comprised this boma, one for each wife. It wouldn’t be long before the younger wife—she couldn’t have been much older than Dalton— would deliver the first of her children. From each wife, as many children as physically possible, Masenga told me. A man’s identity was determined first by bravery, and then by the number of cows, wives and children he maintained. A woman’s identity was derived from a similar kind of bravery — toughness and grit—proved by maintaining the boma and all its inhabitants: house-building; wood-gathering; cow-milking; goat-slaughtering; hide-tanning; meal-preparing; child-bearing; child-burying; child-rearing. All such burdens were necessarily delegated among the several wives.

And so there were many wives, (and many children, and many cows) in the boma, the former two wading barefoot in the raw soupy manure of the latter. Stench and muck filled every walkable space, and I realized quickly that I’d probably never survive a night there due to the bacteria alone.

But I’ll tell you. Man, did I want to.

That initial visit—stunning, enlivening, exhilarating, tender—was cut short when Masenga rushed toward us. “The river is flooding. It’s over its banks,” he hissed, short of breath, wide-eyed. “And it’s getting higher every minute. We must leave now and drive very quickly.”

I clasped the hands of the two young girls and the blind elderly man I’d been hunched closest to, the ones I’d hoped to interview. And I ran away, empty notebook in hand.

That same river which had been hub-cap shallow an hour earlier was, when we finally reached its banks, far too deep and swift for any Jeep to cross. By this time, it was heavy evening in the African wild, and our headlights were the only source of illumination for miles. Weaving along the river for an hour or more, we drove, trying without success to find a place to cross, our lights glinting off of the eyes of 50 or more head of migrating wildebeest and the occasional jackal or warthog. After running out of options, we knew we’d be stuck on the wrong side of the river until waters receded, which could be several hours. Our guides told us to plan on morning. Here are some blankets. Would we mind sleeping in the Jeep?

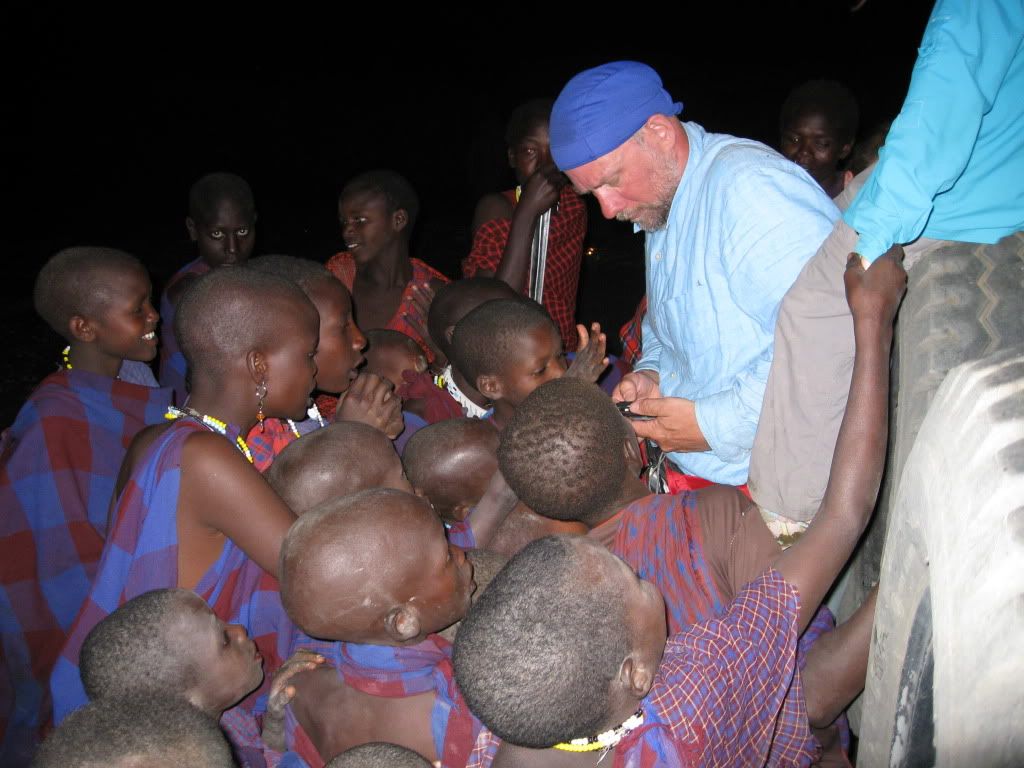

But what about crashing, I suggested nonchalantly, at the boma?

Our Jeep’s low beams framed the boney outline of the familiar thistle hedge, and from the pitch black interior of a corner hut emerged a few dark faces, children I recognized from our daylight visit. Within minutes we were completely surrounded by our Maasai friends, and soon the entire boma and the neighboring boma, too, spilled out into the diffuse pool of headlights. Children’s pearly eyes circled us in the darkness. Their teeth filled their smiles and their smiles filled their faces and their faces filled the night and before we knew it, music filled the air.

As soon as I began “He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands”, the children, at least 25 of them crushing around us, caught right on to singing “in His hands” (or something that sounded like it) over and over again. This turned into a shrill Maasai chant where random children took a solo part and the rest of us shouted (something, but I can’t say what) in response.

We had LDS Primary songs going from atop the Jeep, (imagine a throng of Maasai kids trying to “Do As I’m Doing”), the whole time warm heads nuzzled up to our ribs, small black hands reached and clasped, stroking our shockingly white arms.

A natural splitting-off made for four groups. Group One orbited around our youngest, who had introduced a bunch of boys to the new wonder of Tickle Tag. The flash of his Life Is Good T-shirt raced past, chased by Maasai children, naked arms flailing, bare torsos cloaked in reds and blues. A cloud of laughter and giggling gibberish floated into the sky.

Group Two formed around the Jeep where children and teens discovered Peek-a-Boo, another fabulous game that left a symmetrical series of nostril fog smudges on every window.

Group Three was the beat boxing contingent where Dalton drew an audience with his strange oral rhythmic gifts. They caught right on. And Group Four gathered where our friend Glen from Salt Lake City explained the mysterious amusement that was his digital camera. From where I stood, it looked like he might as well have been unveiling the arc of the covenant. Its radiance lit up the faces of a pressing crowd of kids, who seemed transfixed as this man narrated, in his strange tongue, “Our Year in Pictures.” I caught bits of what he said, since he spoke louder and louder until he was practically barking, (a surefire way to make yourself understood in your tongue when speaking to those who don’t speak a lick of it, by the way.)

The crescent of unblinking eyes locked on the shining images. Glen’s running narration went something like this:

“And this is our skin cancer clinic in Salt Lake City, Utah! Uuuuuuu. Taaaaah.”

“And this is snow. SNOW. White and cold. COLD. Do you know cold?”

“And this is Yosemite. YO. SEH. MEH. TEEEEE.”

It was right about then that Group Five took shape. Behind me, from the darkest part of the darkness, warriors filed in with their spears, coiling into a circle. Their bodies pulsated, the points of their spears rode up and down as they breathed their low, monotone chants. Two young women took me by each arm and led me, singing along with their piercing wails, into the spiral. One slipped two of her bracelets, green and red, onto my wrist. The other girl took the broad, ornate beaded neck disc from her mother dancing nearby, lifted my hair, and fastened the collar around my neck. Some surrounding women, stroking my long hair, (freakishly slick to them, I’m sure), tried to teach me how to make the disc roll and rock up and down to my chanting and the awkward flapping rhythm of my shoulders. (Just a note: White girls can’t flap. Not this one, at least.)

I couldn’t flap, but I could belt, and right then I just couldn’t suppress the singing. So I cut loose, wearing my vocal chords raw, while I wailed a string of their sounds to the moon. It came from the soles of my feet, this wholly joyous wave of celebration, this unison movement and exultation, this mix of darkness and light, fear and belonging, awkwardness and fluidity.

I glanced to the left to see a kelly green T-shirt sidling up next to me. Had my son ever looked so fair, so dimpled, so illumined? Next to him was the tallest, lankiest of all the warriors, who soon pulled Dalton right into the center of the circle, shoved a spear into his hand, and with less than a nod and a half-smile, motioned that he should jump. Jump. The famous Maasai vertical jump. The legendary initiation jump.

Hours later, right up to midnight, we were still jumping. All of us.

So you see we weren’t actually the ones who invited the entire tribe. As it turned out, the entire tribe invited us. Or was it heaven itself that invited us? Heaven and earth, perhaps, invited us to rock, as it were, in the Cradle of Humankind. Shoulder-to-sweaty-shoulder, parch-throated yet intoxicated, heads pitched back singing to Pleiades dangling in that high dome of the infinite with its spin-dizzying splash of fiery stars and pulsing planets, heaving and hollering and hopping, we, the black and white, the ancient and the modern, the Maasai and Mormon, joined in the irrefutable, inexplicable, rollicking and vivid exultation of life.

What Coming of Age moments are most vivid in your memory?

Related posts:

Continue reading at the original source →