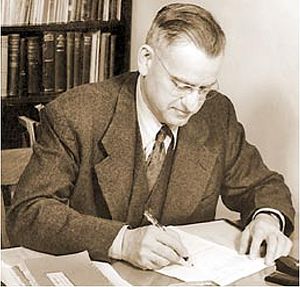

The late Edwin R. Thiele (d. 1986) was a biblical scholar of the mid-20th century. His work in biblical chronology was groundbreaking and ahead of its time.[1] Although some challenge the premises of his chronology for the Israelite and Judahite kings,[2] it remains widely accepted today as the foundation for further study and clarification of biblical chronology during monarchic times.[3] Clearly, Thiele was a gifted scholar and thinker.

Throughout his lifelong pursuit of a rather complicated topic, Thiele learned that you can’t start out by thinking you know what the text already says. In the preface to the second edition of his still important book, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, he explained that beginning with set views about what the text says “is not the attitude of true scholarship, nor is it in accord with biblical principles of religious faith.” He went on to explain:

Scholars impelled solely by a sincere desire for truth and an earnest effort to find it, and religious believers who find in God the very embodiment of truth and in the Hebrew Scriptures its most absolute expression, find little difficulty in putting aside early notions and accepting new light whenever and however it may come.[4]

In response to critics who scoffed that his chronology was “highly complicated,” Thiele aptly replied:

But even if complicated, would that constitute proof that the dates are wrong? The facts of history and science are often far from simple. Life is complicated, but it must be lived. Chemistry and physics are highly complicated but their involved truths must be ascertained if they are to be of service to man. The great achievements of our age were not attained by appeals to simplicity.[5]

As I recently read these words of wisdom from Thiele, I couldn’t help but think of the many silly and immature criticism of Book of Mormon historicity that proliferate online. Far too often, I see people complain that the “apologists” reject the “plain sense” of the text, engage in “mental gymnastics,” and that their arguments amount to “translation not being translation,” “horse not meaning horse,” or, since we are talking about chronology, “year doesn’t mean year.”

One recent commenter listed off a whole host of such trite oversimplifications and then expressed his distaste for the complicated and nuanced approaches to Book of Mormon historicity, “Yuck. Do not want.”

Surely, such distaste does not actually count as much of a counterargument, nor do the strings of statements like those given above, which grossly oversimplify the issue. Take, for example, the statement “a year does not really mean year.” The reality is, the concept of a “year” has not been universally consistent throughout time and across cultures. As Thiele explained, “Months and years among the ancients were not always the same.”[6] The Maya didn’t have a true “year” at all, though they had two time cycles (360-days and 365-days) which approximated it, and both of which are called a “year.”

A similar point could be made with all the other examples. Sure, this might seem complicated. It might require some effort and thinking on our part to understand and wrap our heads around it, but to paraphrase Thiele, does the very fact that it is complicated somehow constitute evidence that it is wrong? As Thiele points out, science and history are complicated, which should come as no surprise to any of us—after all, life itself is complicated.

We simply cannot expect to be able to place the Book of Mormon in an ancient historical context and not have to adjust some of our preconceived notions about what the text says and means. Any historian or scholar will tell you that context is important precisely because it helps us better understand the people, events, and texts from the past. But our understanding can only improve if we are willing to admit that we lack understanding in the first place.

We need to be a little less certain we know what everything means in the Book of Mormon; a little less sure that Nephites were “just like us,” that they saw the way we see, thought the way we think, and understood things the same way we do. In short, we need to read with a little more humility—humility to learn anew from its pages, through both better understanding of the ancient context in which it is set, and from the spirit within its pages. You could almost say we need to have the humility to learn by both study and also by faith (cf. D&C 88:118; 109:7, 14).

For me personally, the Book of Mormon says some pretty different things than what I believed it said 8–9 years ago. And I certainly hope that I understand it differently still in another 8–9 years. Oddly enough, the very thing that keeps bringing me back to the text and leading me to reaffirm it as both history and scripture is precisely the things I don’tunderstand about the book—the questions I still have. It’ll become a rather boring book the day I no longer have questions about it. I pray that day never comes. I hope we all can continue to learn from its pages.

[1]Kenneth A. Strand, “Thiele’s Biblical Chronology as a Corrective for Extrabiblical Dates,” Andrews University Seminary Studies 34, no. 2 (1996): 295–317.

[2]For a couple of alternative chronologies, see Gershon Galil, The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah (New York, NY: Brill, 1996); John H. Hayes and Paul K. Hooker, A New Chronology for the Kings of Israel and Judah and Its Implications for Biblical History (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox, 1988); M. Christine Tetley, The Reconstructed Chronology of the Divided Kingdom (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2005).

[3]See Leslie McFall, “Some Missing Coregencies in Thiele’s Chronology,” Andrews University Seminary Studies 30, no. 1 (1992): 35–58.

[4]Edwin R. Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, new revised edition (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 1983), 20. Originally published in 1951.

[5] Thiele, Mysterious Numbers, 21.

[6] Thiele, Mysterious Numbers, 20.

Continue reading at the original source →