I hadn't thought about it for years...decades, even. I was pondering something completely unrelated, and this image flashed before my eyes of an old, wrinkled Portuguese man sitting in front of a basket of wicker reeds smiling at me. I know who he was. He was the man my mother purchased wicker from. This was back in the mid-eighties and we were living on a tiny island called Terceira in the Açores, Portugal.

I was only a child, somewhere between eight and ten. My memories are not crystal clear, and of course I'm interpreting them now through an adult lens. I don't even know how accurate my memories are. But I remember his brown, wrinkled skin contorted into a smile. I remember his hands, callused from hours of working the tough reeds, softened by hours of soaking in water. All you had to do was take a picture of something made from wicker, give him dimensions, and he would make it for you. He was smiling because I had tried to speak to him in Portuguese, a language of which I remember practically nothing, now.

We had a maid when we lived there. She washed our clothes, cleaned our house, and tended us children. We didn't have a maid because my mom needed a maid, though I'm sure she appreciated the help. We had a maid because we were Americans, and the people of Terceira were poor. Not American poor, with food stamps provided by the government and large vehicles parked out front. They were third-world country poor.

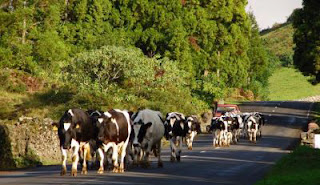

On Terceira, they raised cattle and grew "pig corn." And grapes for wine. The most delicious grapes I've ever eaten, I tasted there. They cooked goat for hours in wine and clay pots buried in the earth. I remember a rubber tree growing in the garden attached to the house we rented for our Church services. We older Primary girls sometimes met in the attic with the Young Women. There were only four of us, on good days. I remember thinking how mature they were.

Our ward spoke both Portuguese and English. We communicated through the few native translators and heavy use of gestures.

My dad took us deep sea fishing, which could be done off the cliffs of the island. A Portuguese man watched us tolerantly and laughingly as we tried to fish with the handmade fishing poles which we found. He laughed at our efforts until I managed to catch a net with a bright purple blob in it. He leapt down from the little rock he had been standing on and stopped my dad from being stung by the Portuguese Man o' War.

To a child who loves the natural world, the cold tropical climate of the Azores was a heaven. I saw blue whale migrations, raised butterflies and picked blackberries. I learned about soil acidity and its affects on the wild hydrangeas. It was there that I learned that my idyllic life was not shared by everyone in the world. And I learned the duties that I, as someone fairly temporally blessed, have towards those who are not as well blessed.

I learned that if an American kills a cow, that American paid for seven generations of cows that would have come from that cow. The law for the Portuguese was not as strict. I learned that sometimes you hire a maid when you don't need one, but do not give handouts. I learned that you open your arms and share what you have. I saw a purple cow, and stacks of corn higher than the houses. I learned about community consciousness. I learned how to slide down a grass hill on a piece of cardboard.

I learned that a falling stone that smashes your brother's finger may nearly kill him from a bone infection months later. I learned about the tiny little Holy Ghost houses on every corner, that worship can be colorful, ubiquitous, and still utterly private. I learned how to hide from a angry bull. I saw people with barely two pennies to rub together scrimping and saving until they could afford to buy a portable baptismal font so they no longer needed to be baptized in the often-frigid ocean. I learned to know that ocean, which once loved never really leaves your heart no matter how many years you live inland. I learned art and beauty flourish even from poverty. Perhaps especially from poverty. I looked into the mouth of a dormant volcano and learned the smell of sulphur.

The people of Terceira were poor, and they were beautiful. I'm grateful for that experience in my life. I'm grateful that, for no particular reason, I once again saw the face of a smiling old man, surrounded by reeds, and wearing the calluses of a thousand baskets on his fingers.