The Know

Several important doctrines that are incomplete or ambiguous in the Bible are taught with clarity and detail in the Book of Mormon. One such doctrine is the Fall of Adam and Eve, a central component of the Plan of Salvation. Without an understanding of the Fall, no understanding of the Atonement can be complete.

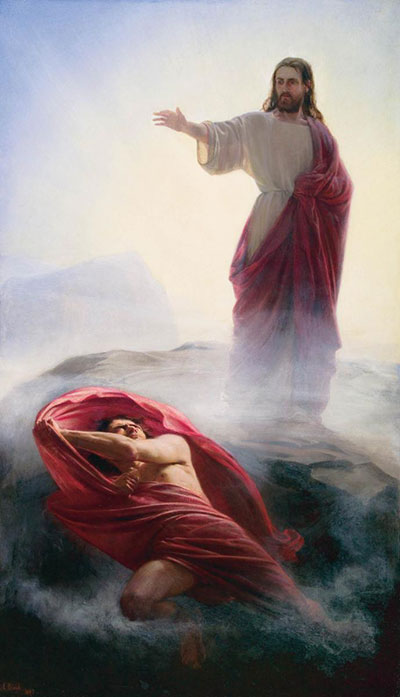

In his instruction to his young son Jacob, Lehi gave a detailed exposition of this doctrine and lays the foundation on which later Book of Mormon prophets would build. Lehi’s teaching connects the Fall of Satan from heaven to the Fall of man on earth (2 Nephi 2:17–18) and indicates that the Fall brought on the conditions of mortality, death, and opposition.

Lehi also stressed a positive side to the Fall, teaching that it is only through the Fall that Adam and Eve could have children, allowing us all to come into the world and experience joy (2 Nephi 2:22–25).

Lehi taught that while man inherited a fallen nature, we nonetheless are not “totally depraved,” as opposed to what has been generally understood and preached concerning of the Fall since the time of Augustine. Instead, we understand from Lehi's teachings that we all now have the freedom to choose “liberty and eternal life, through the great Mediator of all men, or to choose captivity and death, according to the captivity and power of the devil” (2 Nephi 2:27).

For many readers today, Lehi’s teachings may well seem unique and original, but he told Jacob that his teachings about the Fall are based on “the things which I have read” (2 Nephi 2:17), presumably from the plates of brass. The origins of Lehi’s understanding, therefore, came from sources already available to him.

In trying to understand the background to the Book of Mormon’s teachings on the Fall, one LDS scholar, Stephen D. Ricks, examined portrayals of Adam and the Fall in ancient Jewish writings that were not included in the Bible.1 After giving several examples, Ricks provided the following summary of teachings common to both the Book of Mormon and later Jewish texts:

1. Satan’s expulsion from the presence of God was a necessary precondition for the temptation and Fall (see 2 Nephi 2:17–18; Life of Adam and Eve 12–17).

2. Adam’s fall resulted in the conditions of mortality (see 2 Nephi 2:19; 2 Baruch).

3. Man becomes “natural,” i.e., predisposed to sin, but he remains free (2 Nephi 2:26–27; Mosiah 3:19).

4. Adam’s transgression resulted in expulsion from paradise (see Alma 42 [also see 2 Nephi 2:19]; Apocalypse of Moses 28:3).2

These extra-biblical texts come from the era scholars call the Second Temple Period, which is after the time Lehi left Jerusalem. This commonality between Lehi’s teachings and later Jewish texts on the Fall suggests that these doctrines may indeed have been present several hundred years earlier than is previously thought.

Indeed, Bruce M. Pritchett Jr. has found that careful investigation shows that hints of the doctrine can be found in Old Testament writings that likely come from before or around Lehi’s time.3 Pritchett specifically examined Psalms 82:7, Hosea 6:7, Job 31:33, and Ezekiel 28:11–19 as references to the Fall, noting that the Hebrew ke-ʾādām, translated as “like man” in the KJV, could just as easily be read as “like Adam.” Based on his analysis, Pritchett concluded:

Though the Old Testament never refers to Adam’s sin by using the word fall, it does teach or reflect the following basic elements of this doctrine in various scriptures: (1) that Adam’s sin resulted in a metamorphosis from immortality to mortality, (2) that mankind inherited its mortal state from Adam, (3) that all mankind has fallen into sin, and (4) that evil and suffering in the world could be for man’s benefit as well as his punishment.4

Pritchett also noted that “three of these four scriptures (excluding Hosea 6:7) mention the fall of Adam in close connection with the fall of Satan.”5

While these are merely bread crumbs compared to the doctrinal feast that Lehi lays out, it does suggest that there was a foundational understanding of the Fall upon which Lehi could expound.

Moreover, Lehi’s understanding of the Fall may have ultimately stemmed from ancient temple teachings. Kevin Christensen has pointed out that several ideas presented in 2 Nephi 2 are considered to be part of ancient “temple theology,” as proposed by biblical scholar Margaret Barker. This notion includes “not only a discussion of Eden and the creation, but also of the fall of Adam … the fallen angels, the atonement of the Messiah, the Holy One, and coming judgment.”6

John W. Welch notes, “Several of the main doctrines taught by Lehi seem to echo and presage temple types and teachings.” Welch finds that is not only true about 2 Nephi 2, but throughout Lehi’s various discourses found in 2 Nephi 1–4. Lehi’s central themes “are readily at home in the context of the ancient temple typologies.”7 Significantly, three of the four Old Testament passages used by Pritchett—from the Psalms, Job, and Ezekiel—are believed by some scholars to be connected to the temple.8

The Why

As people try to understand better the origins of Lehi’s doctrines relating to the Fall, several interesting things come to light. First, it is worth pointing out that the concepts Lehi teaches in this connection are at home in ancient Israelite and early Jewish beliefs. While Lehi brings these ideas together and expounds on them like no one else before or since, the core ideas were present and available within the Hebrew tradition.

Second, as a byproduct of the first, it becomes apparent that this fuller doctrine of the Fall is not an innovation of either Lehi or Joseph Smith. Rather, it is part of the many plain and precious truths that were lost and find restoration in the Book of Mormon (see 1 Nephi 13:26–42).

Third, recognizing its roots in the Israelite temple tradition is an important clue about the nature of Nephi’s record. It is shortly after this discourse that Nephi reports that his people began making a temple (see 2 Nephi 5:16), and not long afterwards Nephi begins writing his record (see 2 Nephi 5:30–32).

Finally, knowing the connection to ancient temples helps us see the relationship to modern temple worship and the essential elements of the plan of salvation. Like Lehi’s discourse, contemporary Latter-day Saint temple practices relate to themes of creation, fall, and atonement. Altogether, these insights offer all readers precious perspectives that enhance one’s appreciation of the beauty and power of Lehi’s sacred words to his son Jacob.

Further Reading

Kevin Christensen, “The Temple, the Monarchy, and Wisdom: Lehi’s World and the Scholarship of Margaret Barker,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, ed. John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely, and Jo Ann H. Seely (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 2004), 449–522.

Stephen D. Ricks, “Adam’s Fall in the Book of Mormon, Second Temple Judaism, and Early Christianity,” in The Disciple as Scholar: Essays on Scripture and the Ancient World in Honor of Richard Lloyd Anderson, ed. Stephen D. Ricks, Donald W. Parry, and Andrew Hedges (Provo: FARMS, 2000), 595–606.

John W. Welch, “The Temple in the Book of Mormon: The Temples at the Cities of Nephi, Zarahemla, and Bountiful,” in Temples of the Ancient World: Ritual and Symbolism, ed. Donald W. Parry (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Books and FARMS, 1994), 297–387.

Bruce M. Pritchett Jr., “Lehi’s Theology of the Fall in Its Preexilic/Exilic Context,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 3/2 (1994): 49–83.

- 1. Stephen D. Ricks, “Adam’s Fall in the Book of Mormon, Second Temple Judaism, and Early Christianity,” in The Disciple as Scholar: Essays on Scripture and the Ancient World in Honor of Richard Lloyd Anderson, ed. Stephen D. Ricks, Donald W. Parry, and Andrew Hedges (Provo: FARMS, 2000), 595–606.

- 2. Ricks, “Adam’s Fall in the Book of Mormon,” 601.

- 3. Bruce M. Pritchett Jr., “Lehi’s Theology of the Fall in Its Preexilic/Exilic Context,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 3/2 (1994): 49–83. This article was based on Pritchett’s honors thesis. See Bruce Michael Pritchett Jr., Lehi’s Theology of the Fall in its Pre-Exilic/Exilic Context (honors thesis, Brigham Young University, 1989).

- 4. Pritchett, “Lehi’s Theology of the Fall,” 77.

- 5. Pritchett, “Lehi’s Theology of the Fall,” 58.

- 6. Kevin Christensen, “The Temple, the Monarchy, and Wisdom: Lehi’s World and the Scholarship of Margaret Barker,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, ed. John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely, and Jo Ann H. Seely (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 2004), 461.

- 7. John W. Welch, “The Temple in the Book of Mormon: The Temples at the Cities of Nephi, Zarahemla, and Bountiful,” in Temples of the Ancient World: Ritual and Symbolism, ed. Donald W. Parry (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Books and FARMS, 1994), 322.

- 8. For the Psalms, see David J. Larsen, “Ascending into the Hill of the Lord: What the Psalms Can Tell Us About the Rituals of the First Temple,” in Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of the Expound Symposium 14 May 2011, ed. Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks, and John S. Thompson (Orem, UT and Salt Lake City, UT: Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014), 171–188. For Job, see Mack C. Stirling, “Job: An LDS Reading,” in Temple Insights: Proceedings of the Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference—The Temple on Mount Zion, 22 September 2012, ed. William B. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely (Orem, Utah: Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014), 99–143. Ezekiel was a temple priest. See Kevin Christensen, “Prophets and Kings in Lehi’s Jerusalem and Margaret Barker’s Temple Theology,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 4 (2013): 187.

Continue reading at the original source →