The Know

Neither the Old nor New Testaments make any mention of the Plan of Salvation by name, nor is there any detailed description of this plan anywhere in the Bible. Indeed, the word “plan” never occurs in the King James Bible. Although, the term may have come from the original Greek text's phrase “counsel and foreknowledge of God” in Acts 2:23.

The Book of Mormon, however, has several detailed outlines of the Father's foundational and eternal plan. For example, the plan frequently appears in the book of Alma, where Alma the Younger teaches “the plan of redemption” to Zeezrom (see Alma 12), Ammon laid out this “plan” to King Lamoni (Alma 18:39), and Aaron teaches “the plan of redemption” to Lamoni’s father (Alma 22:13).

Later, Alma’s companion Amulek explained “the great plan of the Eternal God” to the Zoramites (Alma 34:9), and Alma testifies of the “plan” to his son Corianton (mentioning the word “plan” ten times in Alma 39–42).1

While Alma, the High Priest of Zarahamla, made great use of the doctrine of the plan, he was not the first Nephite priest to do so. The first explicit exposition of the plan was made much earlier by Jacob, Nephi’s younger brother and first priest of the temple in the city of Nephi. Jacob calls it “the merciful plan of the great Creator,” and “the plan of our God” (2 Nephi 9:6, 13).

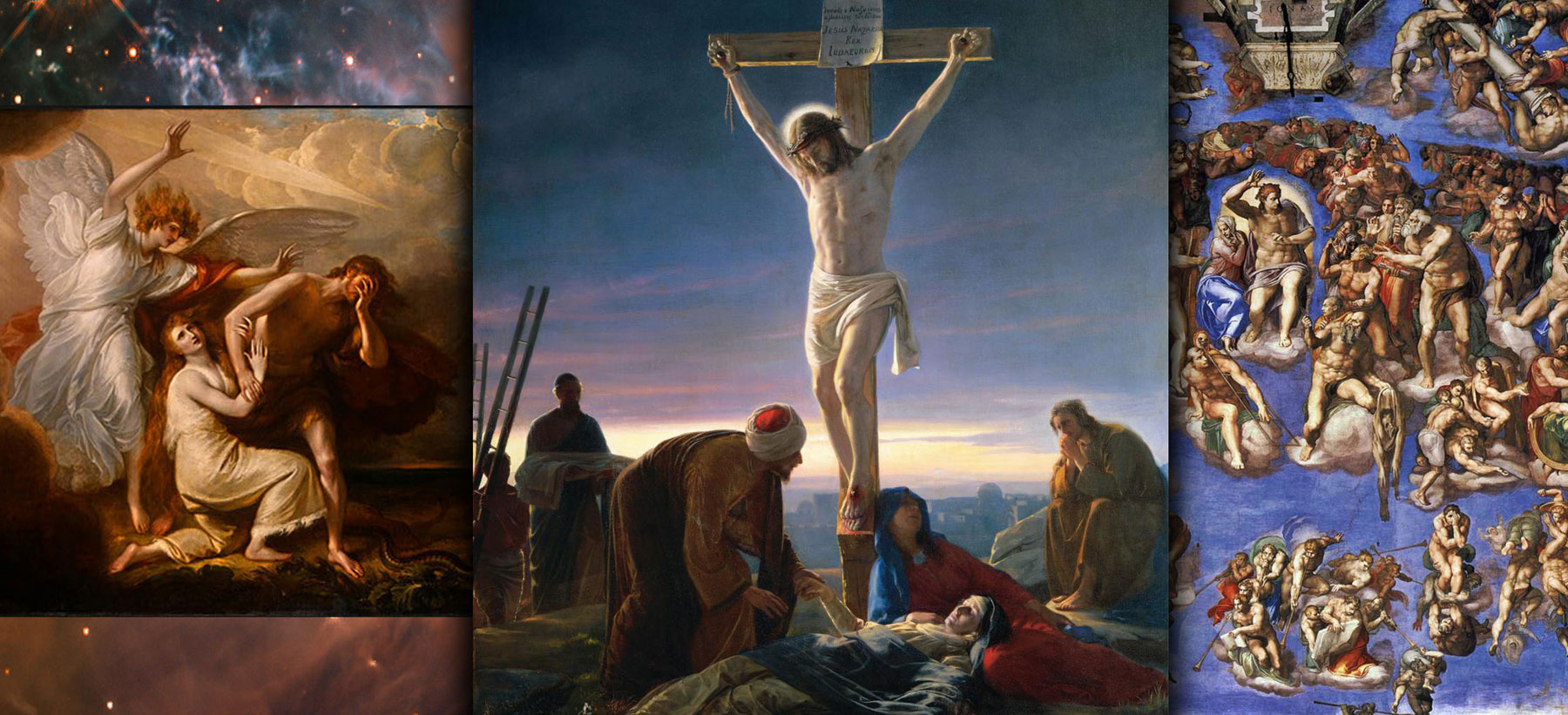

As Jacob described, the plan goes back to the very beginning, centering around “the great Creator” who would allow “himself to become subject unto man in the flesh, and die for all men, that all men might become subject unto him” (2 Nephi 9:5). This would be “an infinite atonement” because “save it should be an infinite atonement this corruption could not put on incorruption” (2 Nephi 9:7).

This atonement is necessary, Jacob explained, because “death hath passed upon all men” and thus, “there must needs be a power of resurrection.” This mortal state came about “by reason of the fall” (2 Nephi 9:6).

Without an atonement, the effects of the fall would have remained to an endless duration” meaning, "flesh must have laid down to rot and...to rise no more” (2 Nephi 9:7). Jacob further explained that without a means of redemption would leave “our spirits … subject to that angel who fell from before the presence of the Eternal God, and became the devil.” In other words, without the atonement we would have become like that fallen angel (2 Nephi 9:8–9).

But God’s merciful plan of salvation, redemption, and happiness provides “a way for our escape from the grasp of this awful monster; yea, that monster, death and hell” (2 Nephi 9:10). That escape is through the atonement, which forces death and hell to “deliver up their dead” “by the power of the resurrection of the Holy One of Israel” (2 Nephi 9:12).

After this, “they must appear before the judgment-seat of the Holy One of Israel; and then cometh the judgment, and then must they be judged according to the holy judgment of God” (2 Nephi 9:15).

As Jacob concluded this part of his covenant speech, he explained that at the judgment, “they who are righteous shall be righteous still, and they who are filthy shall be filthy still.” The filthy “shall go away into everlasting fire, prepared for them” (2 Nephi 9:16). Meanwhile, “the righteous, the saints of the Holy One of Israel, they who have believed in the Holy One of Israel, they who have endured the crosses of the world, and despised the shame of it, they shall inherit the kingdom of God, which was prepared for them from the foundation of the world, and their joy shall be full forever” (2 Nephi 9:18).

Tracing Jacob’s understanding of the plan back one generation earlier, it appears that his inspired summation carried forth the influence of his father’s instructions to him in 2 Nephi 2. Although Lehi never called it a “plan,” he taught these same doctrines in his final blessing to Jacob. In that father’s blessing, Lehi taught, “the way is prepared from the fall of man, and salvation is free” (2 Nephi 2:4). He explained the atonement, that the Holy Messiah “offereth himself a sacrifice for sin” and “layeth down his life according to the flesh, and taketh it again by the power of the Spirit, that he may bring to pass the resurrection of the dead, being the first that should rise” (2 Nephi 2:7–8).

Lehi further explained the coming judgment, noting that after the resurrection, “all men come unto God; wherefore, they stand in the presence of him, to be judged of him according to the truth and holiness which is in him” (2 Nephi 2:10). Lehi taught that there are ultimately two outcomes, “liberty and eternal life, through the great Mediator of all men” or “captivity and death, according to the captivity and power of the devil” (2 Nephi 2:27).

Lehi is also the one who taught Jacob “that an angel of God, according to that which is written, had fallen from heaven; wherefore, he became a devil, having sought that which was evil before God” (2 Nephi 2:17), and that “he seeketh that all men might be miserable like unto himself” (2 Nephi 2:27). These, and others, are the same doctrines taught by Jacob as “the merciful plan of the great Creator” (2 Nephi 9:6).

Though they taught the same doctrines, Lehi’s emphasis was focused more on the fall, opposition, and the agency afforded to all to choose between good and evil. Jacob, meanwhile, put more emphasis on the atonement, resurrection, and the eternal outcome from choosing either righteousness or filthiness. Alma, reflecting the needs of his time, emphasized repentance, redemption, justice and mercy, and the resultant happiness that the righteous will enjoy in the rest of the Lord.

The Why

Comparing the teachings of Lehi, Jacob, Alma and other Nephite leaders is instructive. We learn that, although Jacob was the first to use the word plan to describe the relationship between the creation, fall, and atonement, he was not the first to understand that relationship.

Understanding this interrelationship came to Lehi through revelation, especially as he was admitted into the heavenly council and was allowed to read the heavenly book setting forth the plan, the judgments, and the mercies of God (see 1 Nephi 1:8–19). Jacob passed this sacred knowledge on, just as his father Lehi had blessed him to (see 2 Nephi 2:8).

The doctrines of the great plan may have been especially important to Jacob. These teachings were the final testament he personally received from his father before he passed away.2 Jacob would still have been relatively young when he lost his father to death, and for this reason he may well have especially treasured these precious teachings and took greatest care to pass them along to his people.

Moreover, the awareness and portrayal of the plan are also related to the temple. The temple in Jerusalem was the background for Lehi’s prophetic counsel to his sons;3 and Jacob and Alma were responsible for the temples in the cities of Nephi and Zarahemla, closely aligning their teachings with their high priestly duties.

Latter-day Saint temples today continue to be places that teach God’s eternal plan his children. Everything in the temple—from the architecture, to the instructive dramatizations, to the covenantal ordinances performed there—teaches and makes effective the Plan of Salvation. Jacob’s role as priest gave him special insights and responsibilities to administer these doctrines.

At the same time, we recognize that different Book of Mormon writers taught the plan differently. Even when comparing the teachings of a son with the counsel given to him by his father, we find that each has different emphasis. The differences likely stem from the circumstances in which their respective blessings or discourses were given.

For instance, Lehi’s blessing was given to a son whose older brothers had provided completely opposing models for how to live. No wonder Lehi focused on agency, opposition, and the consequences of sin. Jacob, meanwhile, was a temple priest, likely speaking to his people on the Day of Atonement.4 His emphasis on the Messiah’s atonement, therefore, is also only natural.

In sum, we get a more complete view of the plan when we study Lehi and Jacob together. Adding Alma, Amulek, Ammon, Aaron, and others provides yet a fuller picture of the Lord’s eternal plan of mercy, justice, redemption, salvation, love, and happiness. This continues as we move on into modern revelation and other restoration texts which clarify important parts of the plan, such as the premortal life and the degrees of glory (see Doctrine and Covenants 76; Moses 4; Abraham 3).

Having access to the fullness of the Plan of Salvation is one of the most profound and distinctive blessings that sets Latter-day Saints apart from the world. And it is the Book of Mormon that, first and foremost, repeatedly lays out the foundational doctrines of the Father’s plan. Making this Plan of Salvation known is one of the things the Book of Mormon does best.

Further Reading

Book of Mormon Central, “How Did Lehi Learn So Much About the Fall? (2 Nephi 2:25),” KnoWhy 28 (February 8, 2016).

Book of Mormon Central, “Did Jacob Refer to Ancient Israelite Autumn Festivals? (2 Nephi 6:4),” KnoWhy 32 (February 12, 2016).

M. Catherine Thomas, “Plan,” in Book of Mormon Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2003), 642–643.

Gerald N. Lund, “Plan of Salvation, Plan of Redemption,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow, 4 vols. (New York, NY: Macmillian Publishing, 1992), 3:1088–1091.

Robert J. Matthews, “The Atonement of Jesus Christ: 2 Nephi 9,” in Second Nephi, The Doctrinal Structure, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1989), 177–199.

- 1. See Alma 39:18; 41:2; 42:5; 42:8, 11, 13, 15 (2x), 16, 31. Ten was an important number in both the Bible and the Book of Mormon, where it often signified perfection or completeness. See John W. Welch, “Counting to Ten,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 12, no. 2 (2003): 42–57, 113–114.

- 2. or Lehi’s blessings as a “testament,” see Book of Mormon Central, “Should 2 Nephi Chapters 1–4:12 be Called the ‘Testament of Lehi’? (2 Nephi 3:3)” KnoWhy 29 (February 9, 2016).

- 3. See Book of Mormon Central, “How Did Lehi Learn So Much About the Fall? (2 Nephi 2:25),” KnoWhy 28 (February 8, 2016).

- 4. See Book of Mormon Central, “Did Jacob Refer to Ancient Israelite Autumn Festivals? (2 Nephi 6:4),” KnoWhy 32 (February 12, 2016).

Continue reading at the original source →