The Know

Jacob, NephiÔÇÖs younger brother, in his epic discourse recorded in 2 Nephi chapters 6 through 10, used some powerful imagery to describe the formidable obstacles that face mortals on their path to eternal life. In 2 Nephi 9:10, 19 and 26, he repeatedly used the imagery of an ÔÇťawful monsterÔÇŁ to refer to death and hell, or, more straightforwardly, the death of the body and spiritual death. ┬á┬á

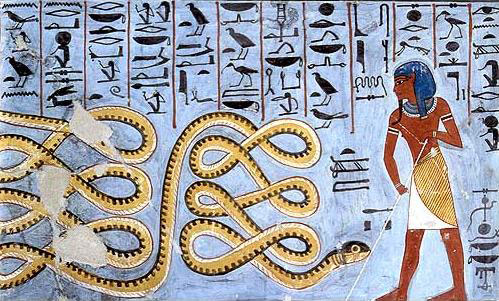

Although the use of the term "monster" is rare in the Bible, Daniel Belnap, BYU Professor of Ancient Scripture, stated, ÔÇťThe personification of death as a monstrous entity is not unique to the Book of Mormon, but found throughout the Bible.ÔÇŁ1 Jacob recited IsaiahÔÇÖs use ┬áof similar imagery to depict the victory of God over ÔÇťRahab,ÔÇŁ ÔÇťthe dragon,ÔÇŁ and the Red Sea, ÔÇťthe waters of the great deep,ÔÇŁ in order to demonstrate the LordÔÇÖs power to redeem his people from Isaiah 51:9ÔÇô10 (2 Nephi 8:9ÔÇô10).

Isaiah uses similar terms elsewhere to likewise portray the future triumph of Jehovah as He delivers Israel from the forces of evil. Isaiah 27:1 reads:

In that day the LORD with his sore and great and strong sword shall punish leviathan the piercing serpent, even leviathan that crooked serpent; and he shall slay the dragon that is in the sea.

Another poignant example is in Psalms 89:8ÔÇô10:

O LORD God of hosts, who is a strong LORD like unto thee? or to thy faithfulness round about thee

Thou rulest the raging of the sea: when the waves thereof arise, thou stillest them.

Thou hast broken Rahab in pieces, as one that is slain; thou hast scattered thine enemies with thy strong arm.

In Psalm 18, the psalmist compares ÔÇťthe snaresÔÇŁ of death and hell to drowning in ÔÇťmany waters.ÔÇŁ He recounted how only the Lord could save him.

The sorrows of death compassed me, and the floods of ungodly men made me afraid.

The sorrows of hell compassed me about: the snares of death prevented me.

In my distress I called upon the Lord, and cried unto my God: he heard my voice out of his temple, and my cry came before him, even into his ears.

ÔÇŽ

He sent from above, he took me, he drew me out of many waters. (Ps 18:4ÔÇô6, 16)

The word of the Lord recorded in Hosea 13:14, an early Israelite text, comes close to the language Jacob employed regarding what the ÔÇťawful monsterÔÇŁ represents:

I will ransom them from the power of the grave (Heb. sheol, ÔÇťhellÔÇŁ); I will redeem them from death: O death, I will be thy plagues; O grave, I will be thy destruction ÔÇŽ┬á

These symbols of Rahab, the (Sea) Dragon, Leviathan (a sea monster), the raging waves of the sea, and other similar imagery are found not only in the Old Testament but also in ancient Near Eastern literature generally.2 Together, they all symbolized the powers of chaos, or those forces that endanger the lives of mortal beings, and are personifications or symbols of death and hell.

A version of the ancient Near Eastern myth of divine combat known as the Canaanite Baal-Cycle, as recorded in writings on tablets found at Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra, Syria), depicts Mot (Death) and Yamm (Sea) as the demonic enemies of Baal, the king of the gods. Although at one point in the story Baal is swallowed up by Death, his ultimate victory over Death and the Sea ensures his reign as king.3

Finally, it can also be noted that there are Mesoamerican parallels to the idea of the ÔÇťchaos monster.ÔÇŁ John Sorenson has elaborated on the fact that ancient Mayan and Aztec myths depict ÔÇťa monster and the waters in which it existedÔÇŁ that ÔÇťsymbolized chaos.ÔÇŁ He noted that the ÔÇťmonstrous creature therein had been fought, defeated, and tamed by a beneficent divinity when the earth was created.ÔÇŁ Sorenson compared this Mesoamerican ÔÇťearth monsterÔÇŁ to similar imagery in the ancient Near East.4

The Why

So, why did Jacob choose a ÔÇťmonsterÔÇŁ as a symbol of death and hell, and why is this important for modern readers to contemplate?┬á

Contextually, Jacob knew that the people in his immediate listening audience would understand this analogy because it was common imagery in the Israelite and wider ancient Near Eastern culture from whence the family of Lehi had come not long before.

Culturally, it is noteworthy that similar imagery is also found in Mesoamerica. The widespread use of this symbolism in the Old and New Worlds emphasizes a point of continuity between the imagery used by biblical prophets such as Isaiah and Hosea and the new setting of LehiÔÇÖs people in their land of promise.

Typically over time, the usage of such images in various civilizations tends to rise and fall in currency. Having survived as an impressionable youth the raging torrents of the ÔÇťgreat deep,ÔÇŁ Jacob himself would have been drawn emotionally to brooding menace of chaos, destruction, and death. Once vivid, however, this imagery seems to have faded somewhat as the Nephites settled in their new land, for this specific language never reappears in the Book of Mormon.

Distinctively, although not uncommon in the Bible and ancient world, what is unique about the use of this imagery in the Book of Mormon is the clarity with which Jacob explained how these symbols apply to the mortal human experience. Jacob left no doubt as he spelled out the significance of the analogy by explaining that these symbols represented both the physical and spiritual deaths ÔÇô two universal obstacles that each person must face and overcome on the path to eternal life. Furthermore, Jacob went on to equate the monster with the devil and with the endless torment of the wicked (2 Nephi 9:19).┬á

Gratefully and optimistically, Jacob also described the reality of the victory of Jehovah over the Monster. He exclaimed: ÔÇťO the greatness of the mercy of our God, the Holy One of Israel! For he delivereth his saints,ÔÇŁ through the Atonement and the Resurrection, freeing all mankind from the power of death and hell, making it possible for everyone to overcome these disastrous barriers.

This understanding of JacobÔÇÖs use of the imagery of the chaos monster adds credence to the doctrine and historicity of the Book of Mormon. Modern readers can well appreciate this powerful depiction of how Christ, our Redeemer and Savior, helps us conquer and overcome our greatest challenges and every obstacle to our eternal salvation.┬á

Further Reading

Allan D. Rau, ÔÇťCheer Up Your Hearts: Jacob's Message of Hope in Christ,ÔÇŁ Religious Educator 14 no. 3 (2013): 49ÔÇô63.

Daniel Belnap, ÔÇťÔÇśI Will Contend with Them That Contendeth with TheeÔÇÖ: The Divine Warrior in JacobÔÇÖs Speech of 2 Nephi 6ÔÇô10,ÔÇŁ Journal of the Book of Mormon and Restoration Scripture 17, no. 1ÔÇô2 (2008): 20ÔÇô39.

David E. Bokovoy and John A. Tvedtnes,┬áTestaments: Links between the Book of Mormon and the Hebrew Bible (Tooele, UT: Heritage Press, 2003), 79ÔÇô87.

Alonzo L. Gaskill, The Lost Language of Symbolism (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003).

Donald W. Parry, Jay A. Parry, and Tina M. Peterson,┬áUnderstanding Isaiah (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1998), 241, 453ÔÇô54.

Robert L. Millet, ÔÇťRedemption through the Holy Messiah (2 Nephi 6ÔÇô10),ÔÇŁ in┬áStudies in Scripture, vol. 7: 1 Nephi to Alma 29, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1987), 119.

- 1. Daniel Belnap, ÔÇťÔÇśI Will Contend with Them That Contendeth with TheeÔÇÖ: The Divine Warrior in JacobÔÇÖs Speech of 2 Nephi 6ÔÇô10,ÔÇŁ Journal of the Book of Mormon and Restoration Scripture 17/1ÔÇô2 (2008): 30.

- 2. Othmar Keel, The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms (London: SPCK, 1972), 47&ndasah;56, 73ÔÇô75.

- 3. See Belnap, ÔÇťI Will Contend,ÔÇŁ 30-31. Also David E. Bokovoy and John A. Tvedtnes, Testaments: Links between the Book of Mormon and the Hebrew Bible (Tooele, UT: Heritage Press, 2003), 79-87; English translations of the Ugaritic tablets may be found in Simon B. Parker, ed., Ugaritic Narrative Poetry (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1994).

- 4. John L. Sorenson, MormonÔÇÖs Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and NAMI, 2013), 455-458. See also idem., An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1985), 187ÔÇô188.

Continue reading at the original source Ôćĺ