The Know

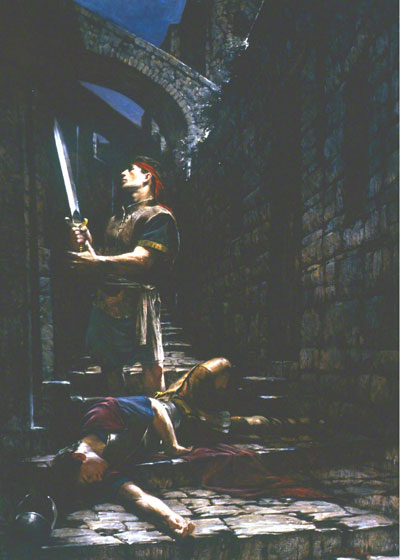

The Book of Mormon contains a number of passages that condemn drunkenness or intoxication, or otherwise portray drunkards as foolish or easily exploitable. At the very beginning of the Book of Mormon, for example, Nephi slayed the treacherous Laban when the latter was found drunk and passed out in the dark streets of Jerusalem (1 Nephi 4:5–7). King Noah and his priests were depicted as immoral and lazy “wine-bibbers” who preyed upon and oppressed their subjects (Mosiah 11:13–15).1 A group of Captain Moroni's Nephite soldiers was freed when he tricked their Lamanite guards into getting drunk (Alma 55:7–16), and the army of Coriantumr was ambushed by the brother of Shared “as they were drunken” (Ether 14:5; cf. 15:22).

The account in Mosiah 22 depicts how the people of Limhi escaped Lamanite bondage by exploiting Lamanite drunkenness. After consulting on the situation (Mosiah 22:1–4),2 Limhi approved Gideon's scheme to deliver a tribute of wine to the Lamanite guards to incapacitate them (Mosiah 22:6–10). Once the guards were drunk, “the people of King Limhi did depart by night into the wilderness” by slipping through “the back wall, on the back side of the city” (Mosiah 22:6).

In this narrative, Limhi’s people are depicted as outsmarting the Lamanites by getting them drunk and taking advantage of the situation. As Brant Gardner elaborated, “The fact that the Lamanites seem to have frequently, or even habitually, gotten drunk is interesting and may have been interpreted, even among the Lamanites, as a moral failing.” Their frequent intoxication impaired these foolish guards’ judgment so much that they “apparently anticipated no efforts that their captives would escape, and especially not at night.”3

In this way the Book of Mormon is consistent with the biblical record. The Hebrew Bible portrays drunkenness as sinful, foolish, and irresponsible.4 In the words of one scholar, drunkenness in the Hebrew Bible is condemned as something that “rendered one insensible and imperceptive, a social nuisance, an economic ruin, and a moral and spiritual reprobate.”5

The Bible stories of Noah (Genesis 9:20–27), Lot (Genesis 19:30–38), Elah (1 Kings 16:8–10), Ben-Hadad (1 Kings 20:13–21), and Nabal (1 Samuel 25:36–38) illustrate the negative consequences of drunkenness. The apocryphal story of Judith and Holofernes shows, much like the story of Nephi and Laban, how a great military leader was killed by the protagonist exploiting his drunken stupor (Judith 10–13). The Book of Proverbs lists drunkenness as a folly, admonishing, “Be not among winebibbers; among riotous eaters of flesh: For the drunkard and the glutton shall come to poverty: and drowsiness shall clothe a man with rags” (Proverbs 23:20–21; cf. 31:4–7). The New Testament likewise views drunkenness negatively (Luke 21:34; Romans 13:13; 1 Corinthians 6:10; 1 Peter 4:3).

The Why

Liimhi had many reasons to think that Gideon's idea would work. His religious and cultural backgrounds gave him many reasons to see how the Nephites might be able to take advantage of the weak propensities of the Lamanite guards.

Beyond that factor, Limhi trusted Gideon’s loyalty, courage, and good judgment. The people of Limhi were highly motivated by their covenants and wanted to escape in order to be baptized (Mosiah 21:32–34). Faith and reason combined to increase Limhi's confidence that the Lord would open a way for the deliverance of His people. The escape was executed only after a careful study of all the possible ways of deliverance (Mosiah 21:36) and after careful planning in advance with Ammon (Mosiah 22:1).

Thus, getting the Lamanites drunk served a practical purpose in the facts of this event. It worked especially well as a narrative tool in Limhi's retelling of this great escape and Mormon’s final formulation of the story to emphasize the cunning of Limhi’s people. Seeing its literary value in this story is not to say that Limhi or Mormon somehow fabricated the detail of the Lamanites getting drunk, but rather that these writers would have readily utilized it as a strong literary tool to retell the story in a way that would echo biblical portrayals of drunkenness.

Ultimately, Limhi thought Gideon’s escape plan would work because of several interplaying factors, not just because the Lamanites got drunk. By taking note of all these factors, readers of the Book of Mormon can appreciate the richness of the text’s narrative and character depictions.

Further Reading

Clyde J. Williams, “Deliverance from Bondage” in The Book of Mormon: Mosiah, Salvation Only Through Christ eds. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate, Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1991), 261–274.

Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 3:380–381.

- 1. Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does the Book of Mormon Mention Wine, Vineyards, and Wine-Presses? (Mosiah 11:15),” KnoWhy 88 (April 28, 2016).

- 2. For Limhi’s council as a sort of type-scene for the divine council, see Stephen O. Smoot, “The Divine Council in the Hebrew Bible and the Book of Mormon,” Studia Antiqua 12, no. 2 (Fall 2013): 16–17.

- 3. Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 3:380–381. Gardner, Second Witness, 3:381, documents drunkenness being condemned in later Aztec culture, as it was “considered a widespread problem.”

- 4. See the discussions in Edgar W. Conrad, “Drunkenness,” in The Oxford Companion to the Bible, ed. Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1993), 171–172; Carol A. Dray, “Ethical Stance as an Authorial Issue in the Targums,” in Ethical and Unethical in the Old Testament: God and Humans in Dialogue, ed. Katharine J. Dell, Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 528 (London: T & T Clark, 2010), 236–240.

- 5. J. Gerald Janzen, “Drunkenness,” in Harper’s Bible Dictionary, ed. Paul J. Achtemeier (San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row, 1985), 229.

Continue reading at the original source →