The Know

The Book of Mormon has much to say about priesthood authority, especially in the book of Mosiah.1 The words “priest” or “priesthood” appear only four times in the books that come before Mosiah, a total of only 3.2 percent of the total mentions in a section of the book that makes up 27 percent of the whole.2 In Mosiah, the text repeatedly asserts that Alma the Elder, and his son Alma after him, acts in his church duties with “authority from God.”3 Why this emphasis on priesthood authority? Where did this authority come from?

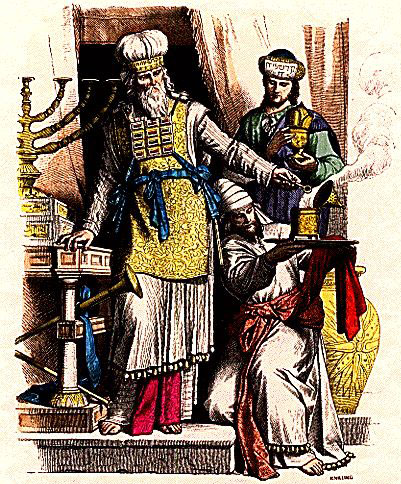

These questions become especially poignant when we remember that there were no Levites among the children of Lehi. The Levites were the tribe of Israel who, by lineal descent, were official bearers of the priesthood. They had the right, by birth, to officiate in the lesser, or Aaronic, priesthood, which is why it is often called the Levitical Priesthood.

This priesthood was passed from father to son within the tribe of Levi, down to the time of Christ, and beyond. However, this was not the only way for a man to be given authority by God. Prophets such as Abraham and Elijah, and the priest Melchizedek, spoke and acted in the name of God, although they were not Levites.

The Book of Mormon begins essentially with two families, that of Lehi and Ishmael. Both were descendants of Joseph (1 Nephi 5:14; 2 Nephi 3:4; Ether 13:7), with Lehi being a descendant of Manasseh (Alma 10:3) and Ishmael said to be of Ephraim.4 Thus, none of the descendants of Lehi could have had access to the Levitical Priesthood that officiated in the temple and performed sacrifices in Jerusalem at the time of Lehi. However, the Book of Mormon narrative depicts, early on, the Nephites building temples (2 Nephi 5:16) and living the Law of Moses, with all its rituals and ordinances (2 Nephi 5:10; 25:24–25, 30).5

Although the Book of Mormon says nothing about Lehi or Nephi being ordained to the priesthood, the Nephites apparnetly did have a priesthood order with authority that they believed was given to them by God. Nephi consecrated his younger brothers as priests (2 Nephi 5:26), and Jacob clearly considered his consecration as priest to be “after [God’s] holy order” (2 Nephi 6:2). The Book of Mosiah presents a similar situation when Alma the Elder as high priest, specified “that none received authority to preach or to teach except it were by him from God” (Mosiah 23:16–17).

Alma the Younger later taught that this priesthood order was the high priesthood “after the order of [God’s] Son,” an order the great priest-king Melchizedek exemplified (Alma 13:1–19). The Melchizedek Priesthood did not need to be passed in succession from father to son, as did the Levitical Priesthood, although it often was (see, e.g., Mosiah 2:11; 6:3). The Levitical Priesthood was passed on from generation to generation within the tribe of Levi. The Melchizedek Priesthood, however, was given only to “just men” (Mosiah 23:17), “on account of their exceeding faith and good works” (Alma 13:3). Lehi, a just man and prophet of God, apparently brought this priesthood authority with him from Jerusalem and passed it on to Nephi, who subsequently ordained his brothers, Jacob and Joseph.6

The Why

With this factual background, one can understand why the book of Mosiah talks so much about priesthood authority. Mormon’s abridgment of the Nephite record in Mosiah depicts a variety of political conflicts and priestly situations. As these events progress, the questions of who has authority and the proper use of priesthood authority come to the foreground. For this reason, Mormon seeks opportunities to emphasize the way in which the Nephite priesthood, being based on the example of Melchizedek, functioned in righteousness.

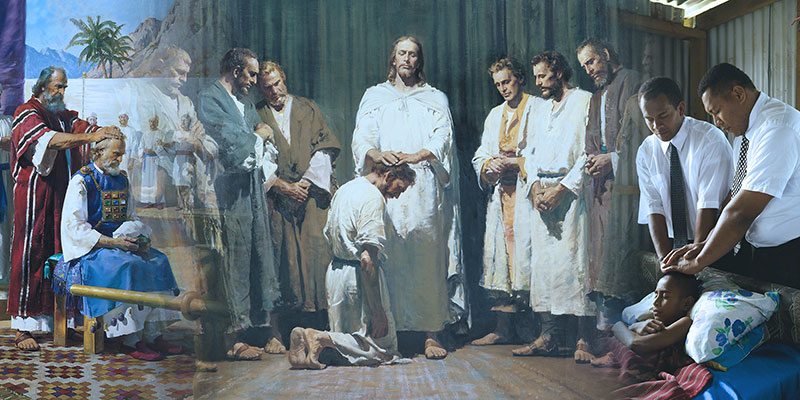

As he looked back over the history of his people, Mormon knew of the importance of being ordained by those in authority, as he knew how the Savior had ordained priesthood leaders in 3 Nephi 11:21, and gave them power in 3 Nephi 18:37 and Moroni 2:1-3:4.

The fact that the Nephites possessed the Melchizedek priesthood proved to be a blessing to them. The Israelites sometimes suffered under wicked and corrupt priests of the Levitical order because these had a lineal right to their office.7In Nephite history, however, the priesthood authority of one wicked lineage or leader woud end and pass to a more righteous and faithful one. For example, priesthood authority passed through the lineage of Jacob, which ended when Jacob's lineage had become "wicked" (Omni 1:2). It was then transfered to Benjamin, because he was “a just man before the Lord” (Omni 1:25).

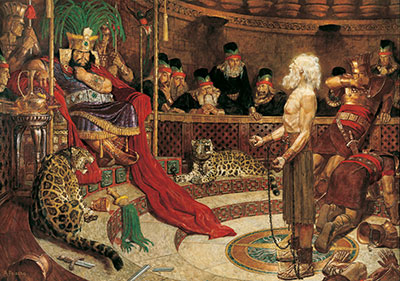

In the middle of the book of Mosiah, although the righteous leader Zeniff had apparently been given authority to consecrate priests, his son Noah abused that privilege, dismissing his father’s priests and appointing corrupt ones in their stead (Mosiah 11:5). The narrative depicts, on the one hand, the swift downfall of the Zeniffite line of authority, with Limhi considering himself without authority to baptize, and on the other hand, the god-protected rise of a righteous lineage in the person of Alma and his descendants. Although Alma had been part of Noah’s council of wicked priests, he repented and God validated the priesthood to which he had legitimately been ordained (Mosiah 18:13, 17–18). The book of Mosiah also makes a point of mentioning that Alma's authority to organize and regulate the covenant communities in Zarahemla was recognized by King Mosiah (Mosiah 26:12) and confirmed by the voice of the Lord (Mosiah 26:14).

The record found throughout the Book of Mosiah, especially the story of King Noah and his priests, add a powerful witness to the lament expressed in Doctrine and Covenants 121:39:

We have learned by sad experience that it is the nature and disposition of almost all men, as soon as they get a little authority, as they suppose, they will immediately begin to exercise unrighteous dominion.

When wicked men rule, the people mourn. As the book of Mosiah notes, when long lines of wicked Jaredite kings kept indefinite political or ecclesiastical authority, the people will inevitably suffer. At the end of the book of Mosiah, King Mosiah justified ending his kingship in Zarahemla saying, “because all men are not just it is not expedient that ye should have a king or kings to rule over you. For behold, how much iniquity doth one wicked king cause to be committed, yea, and what great destruction!” (Mosiah 29:16–18; cf. 29:30–31). Mosiah having been both a king and a priest, these words apply to all who are given authority and exercise it unrighteously.

The book of Mosiah highlights the necessity of righteous living for the exercise of priesthood power and authority. Both King Benjamin and his son, Mosiah, were chosen and able to act with the authority of God because they were righteous leaders who obeyed God’s commandments. Alma the Elder and also his son, Alma, were only able to do God’s work as high priests after they had repented and recommitted themselves to His service. These are powerful examples to us today, and the establishment of the foundational doctrine that men must be given priesthood power to act in God's name is one of the overriding themes of the book of Mosiah, which in turn sets the stage for all that will follow in the book of Alma and all the rest of the Book of Mormon.

Further Reading

Daniel C. Peterson, “Authority in the Book of Mosiah,” The FARMS Review 18/1 (2006).

Daniel C. Peterson, “Priesthood in Mosiah,” in The Book of Mormon: Mosiah, Salvation Only through Christ, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1991), 187–210.

- 1. The term “priest” appears 125 times in the book, either by itself or as part of a compound word, such as “priesthood.” Eldin Ricks’s Thorough Concordance of the LDS Standard Works (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1995), 597–99. The word "authority" appears 44 times, often referring to priesthood, or ecclesiastical, authority.

- 2. Not counting Isaiah’s usage in 2 Nephi 18:2 and the four uses of the word “priestcraft.” Daniel C. Peterson, “Authority in the Book of Mosiah,” The FARMS Review 18/1 (2006).

- 3. See, e.g., Mosiah 13:6; 18:13, 17, 18, 26; 21:33; 23:16–17; 26:7–8; 29:42.

- 4. Erastus Snow, Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 23:184–185.

- 5. The following KnoWhys illustrate some specific examples: Book of Mormon Central, “How Could Lehi Offer Sacrifices outside of Jerusalem? (1 Nephi 7:22),” KnoWhy 9 (January 12, 2016); ibid., “Did Ancient Israelites Build Temples outside of Jerusalem? (2 Nephi 5:16),” KnoWhy 31 (February 11, 2016); ibid., “Did Jacob Refer to Ancient Israelite Autumn Festivals? (2 Nephi 6:4),” KnoWhy 32 (February 12, 2016); ibid., “Why Did the Nephites Stay in Their Tents during King Benjamin’s Speech? (Mosiah 2:6),” KnoWhy 80 (April 18, 2016); ibid., “Why Does King Benjamin Emphasize the Blood of Christ? (Mosiah 4:2),” KnoWhy 82 (April 20, 2016).

- 6. See Rodney Turner, “Three Nephite Churches of Christ,” in The Book of Mormon: The Keystone Scripture, edited by Paul R. Cheesman (Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1988), 100–126, at 101.

- 7. See, for example, 1 Samuel 2:12–17; Jeremiah 5:30–31; Ezekiel 22:26; Zephaniah 3:4; Malachi 1:6–14.

Continue reading at the original source →