The Know

With none of his sons available to succeed him as king, Mosiah instituted governmental reforms. He abolished kingship and established a system of judges, elected, in some form, by “the voice of the people” (Mosiah 29:25).1 The most detailed description of this process is the first election, where it says “they assembled themselves together in bodies throughout the land, to cast in their voices concerning who should be their judges” (Mosiah 29:39; cf. Alma 2:5–6).

Modern readers, however, should not make the mistake of assuming that “the voice of the people” was the equivalent to modern democratic processes. The "voice of the people" played some role in selecting or confirming the king.2 With Judges, successors were still “selected” (Alma 4:16), “appointed” heirs (Alma 50:39; Helaman 2:2), or limited to the previous judge’s sons (Helaman 1:2–4). Mosiah took all the emblems of kingship and “conferred them upon Alma” before he was selected by the people, suggesting he was actually pre-selected by Mosiah (Mosiah 28:20).

In short, the changes were “more nominal and cosmetic that substantive,” as John W. Welch has put it.3 Judges and kings appear to be chosen by, more or less, the same process. Richard Bushman, an expert in early American history, pointed out, "The institution of judgeships, rather than beginning a republican era in Book of Mormon history, slid back at once toward monarchy."4 He added, “The chief judge much more resembled a king than an American president.”5

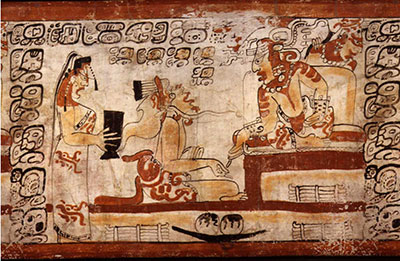

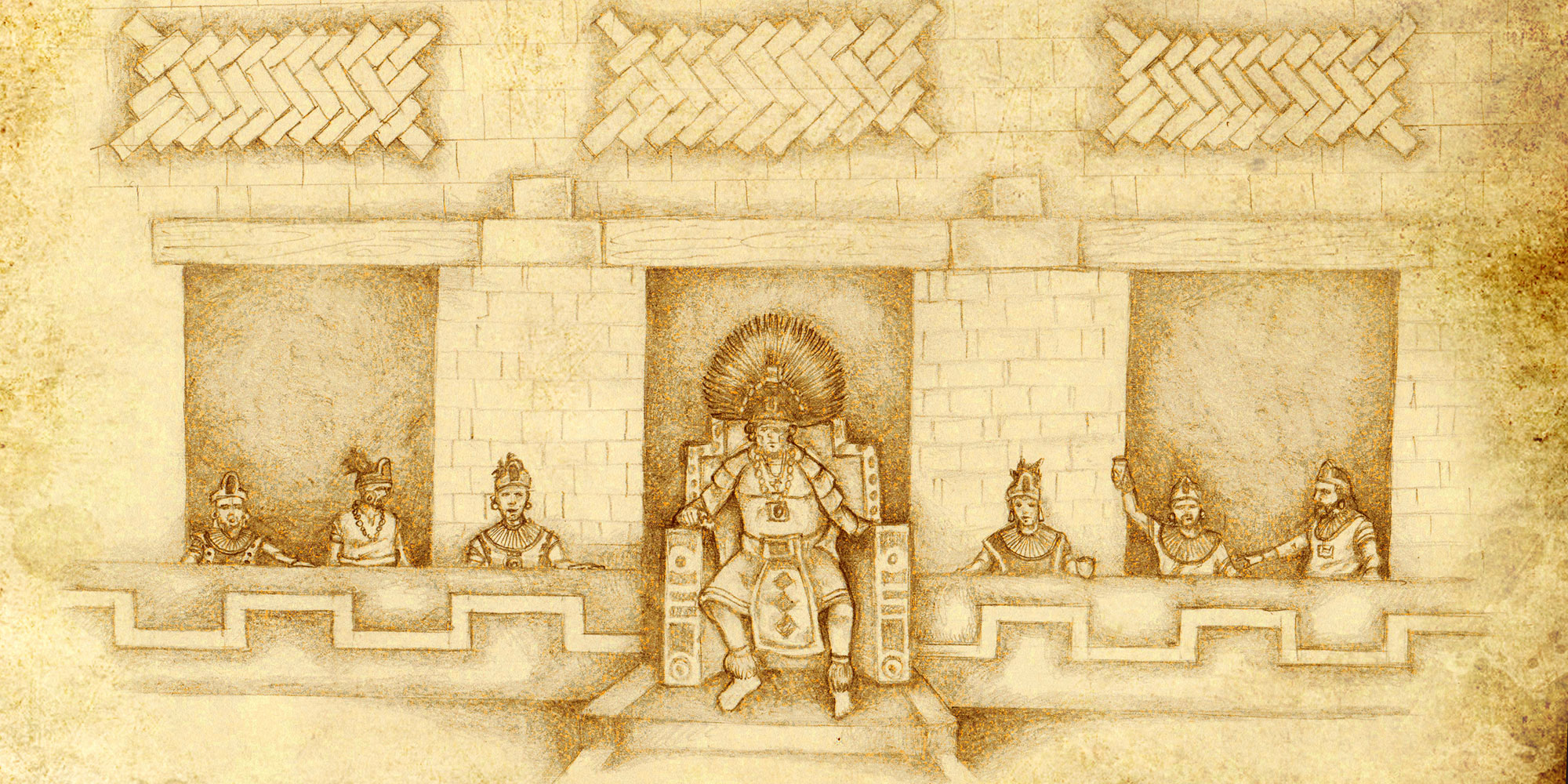

So what, then, were Judges and how were they chosen? Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican political systems may provide some insight. John L. Sorenson explained, “When they ‘cast their voices,’ the expressions would have come from the senior male of a family or sub-lineage.”6 Another scholar declared, “The voice of the people worked itself out in lineages and representatives of lineages.”7 Many ancient societies followed a similar pattern.

The system of judges itself seems to fit Mesoamerican governmental structures. “Mesoamerican monarchies existed on top of a system of rule that divided power among kin-based lineages, each with their own organizational structure.”8 Many cities had a popol nah (“council house”) “where non-ruling elite lineages might meet.” Archaeology “places this type of government in precisely the time period of Mosiah’s shift to the rule of judges.”9 As such, one Book of Mormon scholar proposed:

What Mosiah did was remove the top layer of political authority by abolishing the position of king. This act easily moved rule to the next functioning level [the council of non-ruling elites, or “judges”] … It did not require the creation of any new level of government or even concept of government. It exalted an existing structure to the next higher level.10

Such a shift is not unparalleled in Mesoamerican archaeology, though the evidence comes from post-Book of Mormon times. Inscriptions indicate that in the ninth century AD, instead of a king, at Chichén Itzá had “rule by council, by the heads of different lineages.”11

The Why

Knowing something about how the Nephite judges were probably elected is useful for several reasons. It helps in comparing and contrasting the Nephite system of government with other political regimes, and it illuminates significant causes and effects in the internal narrative of Nephite history.

Although some modern readers have assumed that judges in the Book of Mormon were democratically elected in ways no different than those of contemporary America. However, the careful analysis by Bushman and others suggests otherwise.12 “In the context of nineteenth-century political thought," Bushman concluded, "the Book of Mormon people are difficult to place.”13 It therefore naturally followed, “The Book of Mormon is not a conventional American book. Too much Americana is missing.”14

While 19th-century concepts and forms of democracy are missing, Maya civilization provides a closer comparison with the Nephite political system instituted by King Mosiah. The Maya experience also knew transitions from kingship to judgeship, and also saw the “voice of the people” operating both during and after the monarchy. Taken together, these details point away from 19th-century America and toward pre-Columbian counterparts for Mosiah’s reforms.

Moreover, understanding Mosiah’s political reforms and the social factors which led to them is important for understanding the conflicts that emerge in the books of Alma and Helaman.15 With a system of ruling (and often times, competing) lineages providing “judges” that must lead together in council, the setting was ripe for some to seek greater control. Powerful lineages which had been repressed during the reign of Mosiah’s lineage now sought to capitalize (Alma 2:1–7; 51:5–8). These tensions would define much of Nephite political history for the next four decades.

Further Reading

Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 242–253.

Ryan W. Davis, “For the Peace of the People: War and Democracy in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 16, no. 1 (2007): 42–55, 85–86.

Richard L. Bushman, “The Book of Mormon and the American Revolution,” BYU Studies 17, no. 1 (1976): 1-17, reprinted in Book of Mormon Authorship: New Light on Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1982; reprinted by FARMS, 1996), 201–205.

- 1. For discussion of this transition, se John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: BYU Press and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 215–218.

- 2. See Mosiah 7:9; 19:26; 29:2; cf. 2 Nephi 5:18; Omni 1:12, 19; Mosiah 2:11; 23:6.

- 3. Welch, Legal Cases, 215.

- 4. Richard L. Bushman, “The Book of Mormon and the American Revolution,” in Book of Mormon Authorship: New Light on Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1982; reprinted by FARMS, 1996), 201. This was originally published in BYU Studies 17, no. 1 (1976).

- 5. Bushman, “The Book of Mormon and the American Revolution,” 201.

- 6. John L. Sorenson, An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1985), 314. Sorenson added, “To be sure, those patriarchs would first assess the feelings of those they represented before presuming to speak for their unit. Thus was the political process carried on over much of the world until very recent times.”

- 7. Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 252.

- 8. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers, 251.

- 9. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers, 252. Subscript “2” next to Mosiah (indication that he is Mosiah the Second) silently omitted.

- 10. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers, 252. Subscript “2” next to Mosiah (indication that he is Mosiah the Second) silently omitted.

- 11. David Drew, The Lost Chronicles of the Maya Kings (Berkley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1999), 372. This parallel is pointed out by Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers, 251–252.

- 12. Richard Bushman has pointed out many ways in which the “reign of the judges” was “a far cry from the republican government Joseph Smith knew.” Bushman, “The Book of Mormon and the American Revolution,” 201.

- 13. Bushman, “The Book of Mormon and the American Revolution,” 202–203. Bushman added, “The Book of Mormon was an anomaly on the political scene of 1830” (p. 203).

- 14. Bushman, “The Book of Mormon and the American Revolution,” 205.

- 15. One influencing factor appears to be Mosiah’s recent translation of the Jaredite record. See Book of Mormon Central, “What Do the Jaredites Have to Do with the Reign of the Judges? (Mosiah 28:11),” KnoWhy 106 (May 23, 2016). Other influencing factors are explored by Welch, Legal Cases, 211–215.

Continue reading at the original source →