The Know

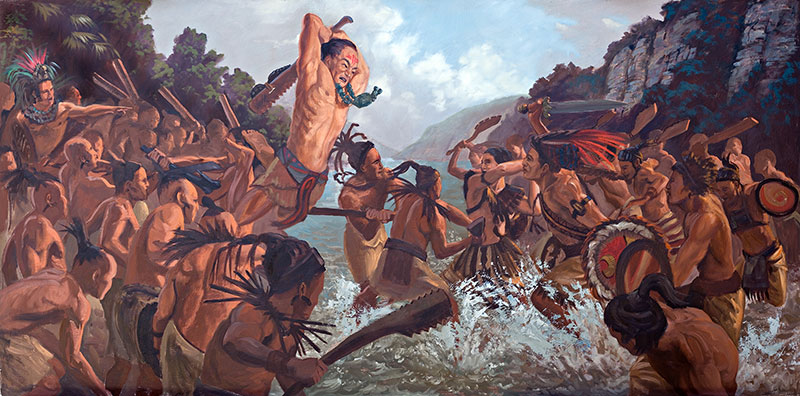

Apostasy and rebellion mark the opening of the book of Alma. In Alma 2–3 a dissenter named Amlici “had, by his cunning, drawn away much people after him.” This group “began to endeavor to establish Amlici to be a king over the people” (Alma 2:2). Amlici was a follower of the apostate teachings of Nehor, “the man that slew Gideon by the sword” (v. 1).

Through his cunning, Amlici drew many Nephites into apostasy and political rebellion, resulting in a national crisis. The Nephites, under the command of Alma the Younger, suddenly faced a bloodthirsty Lamanite-Amlicite alliance in open warfare (v. 24). The Nephites ultimately prevailed, but only after a “great slaughter” which included Amlici’s demise at the hands of Alma (vv. 18–38).

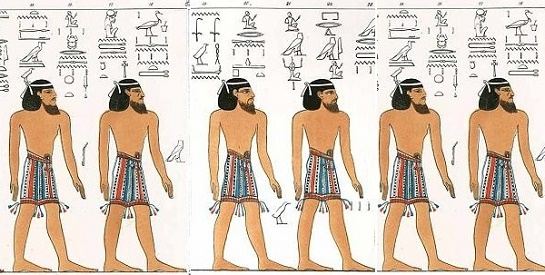

In this context, Mormon expounds on the nature of the Lamanite “curse” in Alma 3. After detailing Lamanite war regalia, Mormon explained, “The skins of the Lamanites were dark, according to the mark which was set upon their fathers, which was a curse upon them because of their transgression and their rebellion against their brethren, who consisted of Nephi, Jacob, and Joseph, and Sam, who were just and holy men” (Alma 3:5–6).

Mormon clarified that this curse was the result of their violent and rebellious dispositions (v. 7). This was done, Mormon specified, so that the Nephites “seed might be distinguished from the seed of their brethren, that thereby the Lord God might preserve his people, that they might not mix and believe in incorrect traditions which would prove their destruction” (v. 8).

As such, Mormon appeared to couch the issue of the Lamanite mark and curse in terms of religious and cultural identity, not skin pigmentation. “Whosoever suffered himself to be led away by the Lamanites,” or otherwise identified as a Lamanite, had the same “mark set upon him” (v. 10). On the other hand, “whosoever would not believe in the tradition of the Lamanites, . . . were called the Nephites, or the people of Nephi” (v. 11).

The curse would linger on the Lamanites “except they repent of their wickedness” and turn to the Lord (v. 14). Indeed, there is flexibility in Nephite-Lamanite religious and cultural identity and the blessings and curses associated with it. Thus, the Lord promised, “He that departeth from thee [Nephi] shall no more be called thy seed; and I will bless thee, and whomsoever shall be called thy seed, henceforth and forever” (v. 17).

Taken in its entirety, Alma 3 appears to illuminate the following about the nature of the Lamanite curse. First, the “curse” of the Lamanites included not just the distinguishing “mark” of darkened “skins” but the ultimate outcome that they would believe “in incorrect traditions which would prove their destruction” (i.e. divine judgment).

Second, the dark “skins” in question were possibly clothing, not flesh. This is seen in Mormon’s apparent description of the “skins” being garments the Lamanites wore.1

Third, the curse was not indefinitely fixed, but was as fluid as the religious and cultural identity of both “Nephite” and “Lamanite.” Those who turned away from the Nephites and became Lamanites, either through intermarriage or apostasy, inherited the curse, while those Lamanites who repented and turned to the Lord were saved from the curse.

The Why

As explored in a previous KnoWhy, the issue of racial identity and ethnicity in the Book of Mormon is complex.2 Readers should avoid simplistic approaches that fail to appreciate the nuances of ancient cultural, religious, racial, and ethnic sensibilities. Readers are vulnerable to misread completely the Nephite record if uncritically assumed modern attitudes or outlooks on race and multiculturalism go unchecked. Poor readings do a great disservice to those who want a fuller and more accurate picture of both Nephite and Lamanite culture.

For instance, it would be easy enough to claim the Book of Mormon is racist, or exhibiting antipathy towards a person or group based on skin pigmentation. If read uncritically, Alma 3 could be seen as saying dark skin pigmentation is a sign of divine punishment, or as disapproving of any kind of exogamy (marriage outside of a cultural or racial group) or interracial marriage. However, this fails to take into consideration the context of Alma 3.

At this point in Nephite history, ethnic and religious strife between the Nephites and Lamanites-Amlicites was so severe that war and bloodshed resulted. It was a politically vulnerable moment for the Nephite people, who were transitioning from a monarchy to an unprecedented rule of judges (Mosiah 29).3 The murderous Nehor and his followers exacerbated the insecurities of a regime change by exploiting the situation to further their apostate ends, plaguing the Nephites with persecution, priestcrafts, and other crimes (Alma 1). Having inherited Nehor’s teachings and penchant for violence, and wanting to overthrow the Nephite judges and revert to a monarchy, Amlici and his followers pushed Nephite tolerance to the breaking point by joining forces with the Lamanites.

From a Nephite perspective, then, intermarriage with the Lamanites or Amlicites at a time of war would’ve been unthinkable. It may have even been perceived as a form of treason, or seen as showing support to Amlici and his attempted coup of the Nephite government. In order to ensure national survival, exogamy was out of the question. The Nephites would have to coalesce and unite to defeat this new threat.

The Nephite reluctance towards exogamy also makes sense in light of ancient Israelite marriage culture. At an equally volatile time in their history, the children of Israel were forbidden from intermarrying with Canaanites as they came to repossesses the land of promise, lest they abandon their covenants with the Lord. “Thou shalt smite them, and . . . make no covenant with them, nor shew mercy unto them,” the Lord commanded, as the Israelites and Canaanites were at war. “Neither shalt thou make marriages with them; thy daughter thou shalt not give unto his son, nor his daughter shalt thou take unto thy son” (Deuteronomy 7:2–3).

Moses’ successor Joshua repeated this prohibition, warning that intermarriage with Canaanites or other non-Israelites would result in “snares and traps” for the Israelites (Joshua 23:11–13). This warning was given even long before the Israelite conquest of Canaan, as the Lord undoubtedly foresaw the potential problems that would face Abraham’s seed (Genesis 24:3; 26:34–35; 27:46; 28:6–9).

To be clear, this is not to say that interracial or intercultural marriage is inherently sinful or dangerous.4 If this were so, then the Lord’s promises to repentant Lamanites who rejoined the Nephites would be self-defeating. Rather, readers should recognize that the Book of Mormon describes instances where intermarriage was not expedient because of specific moments of political tension, ethnic strife, inter-cultural contention, and outright warfare between the Nephites and Lamanites.

As one Book of Mormon scholar put it, “The prohibition against intermarriage” in Alma 3 was “to protect the Nephites from these dangerous false traditions.” It is clear that “the danger the Book of Mormon prophets preach[ed] against [was] not the problem of origins, but the attractiveness of culture. Adopting what ha[d] become Lamanite lifestyles would destroy Nephite cultural ideals.” This included the Lamanite values involving “kings, social stratification, and fine clothing,” which would have undermined “the egalitarian Nephite” ideal.5

While the principles of the gospel of Jesus Christ found in the Book of Mormon are timeless, some of its other teachings are largely couched in specific historical contexts. These contexts should serve as interpretive guides, especially for teachings that may trouble modern readers. After all, Mormon as a record keeper was trying to make sense of Nephite history by reacting to specific historical occurrences and interjecting theological and moral rationales to make sense of those occurrences. In order to discern what the Book of Mormon teaches on any number of topics, including race and ethnic identity, it is, therefore, essential for readers to carefully look at the context underlying Mormon’s reconstruction of his people’s history.

Further Reading

Book of Mormon Central, “What Does it Mean To Be a White and Delightsome People? (2 Nephi 30:6),” KnoWhy 57 (March 18, 2016).

Ethan Sprout, “Skins as Garments in the Book of Mormon: A Textual Exegesis,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 24 (2015): 138–165.

Hugh Nibley, Since Cumorah, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley: Volume 7 (Salt Lake City, UT and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 215–220.

- 1. Ethan Sprout, “Skins as Garments in the Book of Mormon: A Textual Exegesis,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 24 (2015): 138–165, esp. 158–163.

- 2. Book of Mormon Central, “What Does it Mean To Be a White and Delightsome People? (2 Nephi 30:6),” KnoWhy 57 (March 18, 2016).

- 3. On this transition, see Book of Mormon Central, “How Were Judges Elected in the Book of Mormon? (Mosiah 29:39),” KnoWhy 107 (May 25, 3016).

- 4. The Church today “disavows” any teachings that “mixed-race marriages are a sin.” See “Race and the Priesthood,” online at LDS.org.

- 5. Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 4:74.

Continue reading at the original source →