The Know

The accounts of both the missionary efforts of the sons of Mosiah (Alma 17–26) and the earlier account of the Zeniffite colony (Mosiah 9–24) give readers a glimpse of Lamanite politics. In the Lamanite political system, there was a “king over all the land” (Alma 18:9; 20:8) who “appointed kings over all … lands” under his rule (Mosiah 24:2).

As political scientist Noel B. Reynolds noticed, the Lamanite government was “a very different system” than that of the Nephites, “one of tributary kings appointed by the superior monarch, not by a prophet.” Reynolds commented that this was “more like the system that appears to have prevailed in ancient Mesoamerica.”1 In fact, both Mesoamerica and the ancient Near East had systems of kings similar to that described among the Lamanites.

In the ancient Near East, this patron-client or suzerain-vassal relationship was typical when larger empires conquered smaller states,2 as happened to Israel and Judah (2 Kings 17:3; Lamentations 1:1 NRSV). According to ancient Near Eastern legal scholar Raymond Westbrook, “Vassalage can entail many different degrees of political control, from province to sphere of influence.”3 This resulted in networks of subordinate kings (vassals) who had pledged allegiance to a “great king,” or suzerain.

Familial language is commonly used to describe the nature of these relationships—the suzerain is “father” to the subordinate king, who is described as his “son.”4 The relationship usually involved tribute payments to the suzerain. During the reigns of David and Solomon, for instance, Israel had vassals which “were expected to pay tribute to the Israelite king” and “even the simple failure to pay the yearly tribute, would be regarded … [as] a direct challenge to the imperial claims” of the God of Israel.5

The Lamanite political hierarchy, in the words of John L. Sorenson, also “rings a Mesoamerican bell.”6 In describing the political system of the Classic period (ca. AD 250–900), Mayanists Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube argued that the evidence “points to a pervasive and enduring system of ‘overkingship’ that shaped almost every facet of the Classic landscape.”7

Political ties binding overkings with subordinate kings were at once very personal, yet highly tenuous.8 Professor Sergio Quezada explained, “Multiple factors may have led one Maya to accept another’s lordship …. Such factors included protection, kinship, convenience, war, or the simple quest for recognition of a title."9 Vassal rulers were expected to make tribute payments to their overlords,10 and overkings did not hesitate to appoint rulers when local dynasties were uncooperative.11

The Why

In 2013, John L. Sorenson concluded, “At least for a century or more for the Mesoamerican Late Pre-Classic period (ca. 100 BC–AD 50) the Book of Mormon record portrays its peoples in a political situation that sounds very much like” that of major Mesoamerican centers at the time.12 Indeed, Martin and Grube affirmed that at least “elements” of the Classic Maya political system, “took root in various parts of Mesoamerica between 100 BC and AD 100.”13 The Lamanites’ hierarchy of kings, as one scholar concluded, “fit[s] very comfortably into a Mesoamerican context.”14

This context, along with the ancient Near Eastern background, illuminates the account of the confrontation between Lamoni and his father (Alma 20:8–16). Although typically understood as just a familial quarrel,15 the ancient reality is that it was a political dispute.16 It is likely that the “great feast” Lamoni was supposed to attend was an occasion for him to pay tribute. Failure to attend was seen as both a breach of etiquette and a sign of rebellion.17

When the “king over all the land” saw that Lamoni was traveling with the prince of an enemy state, on his way to use his political clout to liberate others of Nephite nobility in captivity,18 his suspicions were intensified (Alma 20:10–13). He insisted that Lamoni prove his loyalty by slaying the enemy prince (v. 14). Lamoni’s refusal was nothing short of treason, in the high king’s mind, leaving him with no other choice but to exact capital punishment (v. 16).19

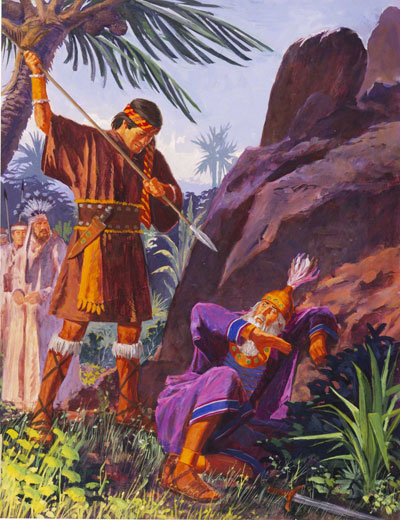

Further indication of the political nature of the altercation can be seen when Ammon arose to defend Lamoni (Alma 20:17). In the king’s eyes, Ammon was no doubt fulfilling the role of Lamoni’s new suzerain. Upon his defeat, the king made several political concessions. He was prepared to relinquish half his kingdom to his new conqueror (v. 23), but all Ammon required was that he release his political control over Lamoni (v. 24–26). The king also granted the release of Ammon’s brethren (v. 27).

The king likely expected that if he lived, he would be Ammon’s prisoner, and be subject to torture and public humiliation. Yet, the “old king was escaping with not only his life but his political power intact—a complete reversal of his expectations after defeat.”20 This turned a highly volatile political moment into an opportunity for the Lord to use Ammon and Lamoni as “tools of positive change.”21

Ammon’s refusal to seek power and take advantage of the situation, and instead show loyalty, love, and mercy softened the high king’s heart. He was “greatly astonished” (Alma 20:27) and had a strong desire to learn what could make a man pass up such great political power. When the opportunity came, he too was willing to give up all the political power he had attained to “receive [the] great joy” that comes from the gospel of Jesus Christ (Alma 22:15).

Further Reading

Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 300–302.

John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 362–380.

Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 4:311–319.

John L. Sorenson, An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1985), 227–232.

- 1. Noel B. Reynolds, “Nephite Kingship Reconsidered,” in Mormons, Scripture, and the Ancient World: Studies in Honor of John L. Sorenson, ed. Davis Bitton (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 164.

- 2. Raymond Westbrook, “Patronage in the Ancient Near East,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 48, no. 2 (2005): 210–233.

- 3. Westbrook, “Patronage in the Ancient Near East,” 223.

- 4. F. Charles Fensham, “Father and Son Terminology for Treaty and Covenant,” in Near Eastern Studies in Honor of William Foxwell Albright, ed. by Hans Goedicke (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971), 121–135; J. David Schloen, The House of the Father as Fact and Symbol: Patrimonialism in Ugarit and the Ancient Near East (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2001), 255–262. This is also mentioned in Westbrook, “Patronage in the Ancient Near East,” 212–214. J. J. M. Roberts, Bible and the Ancient Near East: Collected Essays (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2002), 149: “To refer to a suzerain as ‘father,’ a vassal as ‘son,’ or an ally as ‘brother’ characterizes in familial terms the nature of the power relationship between the two treaty partners.” T. Benjamin Spackman, “The Israelite Roots of Atonement Terminology,” BYU Studies Quarterly 55, no. 1 (2016): 53–57 discusses this language in the context of covenants with deity, which are themselves patterned off of the suzerain-vassal treaties.

- 5. Roberts, Bible and the Ancient Near East, 328–329.

- 6. John L. Sorenson, An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1985), 230.

- 7. Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube, Chronical of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya, 2nd edition (London, Eng.: Thames and Hudson, 2008), 19.

- 8. Martin and Grube, Chronical of the Maya Kings and Queens, 20.

- 9. Sergio Quezada, Maya Lords and Lordship: The Formation of Colonial Society in Yucatán, 1350–1600, trans. Terry Rugeley (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014), 9.

- 10. Martin and Grube, Chronical of the Maya Kings and Queens, 21; Quezada, Maya Lords and Lordship, 13 affirms that tribute played a role in the postclassic era as well.

- 11. On appointment of rulers, see the example of the conquest of Uaxactún and Tikal in the late fourth century AD, where new rulers who are family to the high-king are appointed to the thrones in Linda Schele and David Freidel, A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya (New York, NY: William Morrow, 1990), 157–158. Also see the discussion in Sorenson, An Ancient American Setting, 230–231; Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 3:405–406.

- 12. John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 365.

- 13. Martin and Grube, Chronical of the Maya Kings and Queens, 17.

- 14. Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 302.

- 15. See, for example, D. Kelly Ogden and Andrew C. Skinner, Verse by Verse: The Book of Mormon, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2011), 1:427, which describes the even strictly in familial terms: “Lamoni’s father … became so furious at his son for being with a Nephite that he tried to kill him.”

- 16. Gardner, Second Witness, 4:315: “Lamoni’s father is not making only a paternal or personal request but issuing a political order as Lamoni’s overlord.” Given that the terms of kinship such as “father” and “son” could be used to represent the relationship of suzerain to vassal, it is possible that Lamoni and his “father” the overking were not actually family at all. Mesoamerican examples where the family of the high king are appointed as subordinate kings (see n.11), however, certainly make it possible that a real father-son relationship existed between Lamoni and the unnamed overking.

- 17. See Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers, 301–302; Gardner, Second Witness, 4:313–314.

- 18. Gardner, Second Witness, 4:312: “By calling Antiomno of Middoni ‘a friend,’ Lamoni is not just speaking of an associate who has cordial feelings toward him. They are both kings, and ‘friend’ here means ally. City-states in Mesoamerica were frequently at war with other cities. Alliances were forged and broken. Allied kings, however, paid each other frequent inter-city visits with strong political overtones. Thus, Lamoni is indicating that Antiomno is an ally of whom he has some expectations, just as Antiomno would also have expectations of him. Such formal state visits, during the Maya Classic period, would be recorded in stone. The ‘flattery’ Lamoni proposes is not just a friendly conversation but a delicate political negotiation aimed at persuading a fellow king to reverse his decision.” Also see Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers, 301. On Friend meaning ally, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Converted Lamanites Call Themselves Anti-Nephi-Lehies? (Alma 23:17),” KnoWhy 131 (June 28, 2016). S. Kent Brown, Voices from the Dust: Book of Mormon Insights (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communication, 2004), 104–106 pointed out that Lamoni and Ammon are following standard protocol for freeing enslaved persons aboard in the ancient Near East.

- 19. Gardner, Second Witness, 4:315: “Lamoni’s father is not making only a paternal or personal request but issuing a political order as Lamoni’s overlord. He is forcing Lamoni to choose an allegiance—either to his overlord and father, or to this Nephite. Refusal would be rebellion against his father and all of his father’s allies. He would declare antagonism toward former allies and renounce political, kinship, and economic connections without having replaced them. In an ancient society, such a move could be literally fatal.”

- 20. Gardner, Second Witness, 4:317. Gardner noted, “Even if a king did not die in combat, someone of his status in Maya society would be kept for ritual display, periodic torture, and eventual sacrifice.”

- 21. Ogden and Skinner, Verse by Verse: The Book of Mormon, 427.

Continue reading at the original source →