The Know

While journeying “from the land of Gideon southward, away to the land of Manti,” Alma was astonished to be reunited with the sons of Mosiah, who were journeying “towards the land of Zarahemla” (Alma 17:1). After reaffirming that the sons of Mosiah had remained true to the faith since their conversion (vv. 2–4), Mormon’s narrative spans the next ten chapters in recounting their experiences through a flashback sequence (Alma 17:5–27:15).

What was especially remarkable is that Alma 17–27 actually contains a flashback within a flashback—or what Grant Hardy calls “a subsidiary flashback”(Alma 20:30–Alma 21:14).1 The end of Alma 20 recounts how Ammon and Lamoni rescued Aaron and his missionary companions from the king of the land of Middoni (Alma 20:28–30). Then, Mormon immediately presents Aaron’s record of his preaching, imprisonment, and rescue (Alma 21:1–17).

These flashbacks are structured the way they are to allow “for the retelling of another crucial event—the destruction of the border city of Ammonihah by the Lamanites—from two perspectives (Alma 16:1–11/25:1–2).”2 In Alma 16, readers see this event from Alma’s perspective inside the land of Zarahemla,3 while Alma 24–25 gives the backstory, illuminating why the Lamanites were so angry and had gone to wipe out Ammonihah.

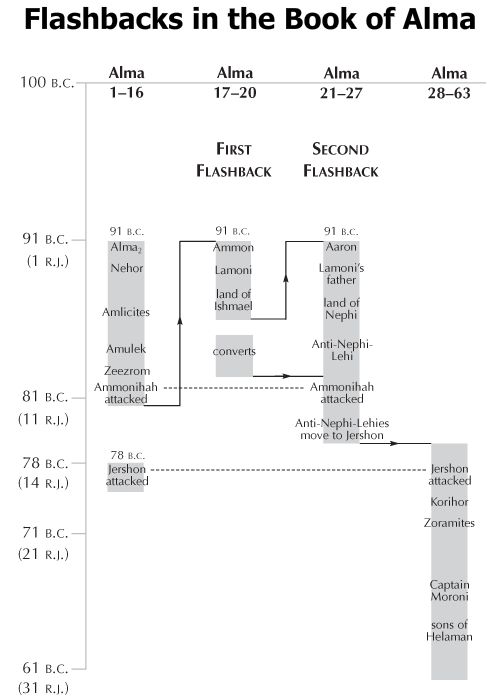

As seen in the accompanying chart,4 Mormon’s structuring of these chapters seamlessly transitions readers into the remainder of the book of Alma. This includes the rise of the Anti-Nephi-Lehies (Alma 23–24, 27),5 Alma’s ministry among the Zoramites (Alma 31–35), and the so-called “war chapters,” including the exploits of chief captain Moroni (Alma 43–63).

The Why

The sophistication and intricacy of Mormon’s record can easily be discerned in these chapters. Briefly said, “These flashbacks are yet another evidence of the complexity of the Book of Mormon. It is quite remarkable how these historical accounts fit so neatly together.”6 There is no fumbling or confusion on Mormon’s part, who, despite the “twists and turns of [the] narrative . . . handles them smoothly.”7

These chapters are also significant because they offer a compelling view of the ideal image of what it means to be a righteous missionary.8 It seems that Mormon was skillfully integrating valuable information and teachings from each missionary's perspective as part of a larger sketch which sought to fully explain Ammonihah's complete annihilation. This he did by carefully embedding flashbacks, including, most impressively, a flashback within a flashback, into the narrative.

Further Reading

Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), 104–105.

Clyde J. Williams, “Instruments in the Hands of God,” in The Book of Mormon: Alma, the Testimony of the Word, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 89–105.

- 1. Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), 104.

- 2. Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 104.

- 3. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why was the City of Ammonihah Destroyed and Left Desolate? (Alma 16:9–11),” KnoWhy 123 (June 16, 2016).

- 4. From John W. Welch and J. Gregory Welch, Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), chart 30.

- 5. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Converted Lamanites Call Themselves Anti-Nephi-Lehies? (Alma 23:17)” KnoWhy 131 (June 28, 2016).

- 6. Welch and Welch, Charting the Book of Mormon, chart 30.

- 7. Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 104–105.

- 8. Clyde J. Williams, “Instruments in the Hands of God,” in The Book of Mormon: Alma, the Testimony of the Word, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 89–105.

Continue reading at the original source →