The Know

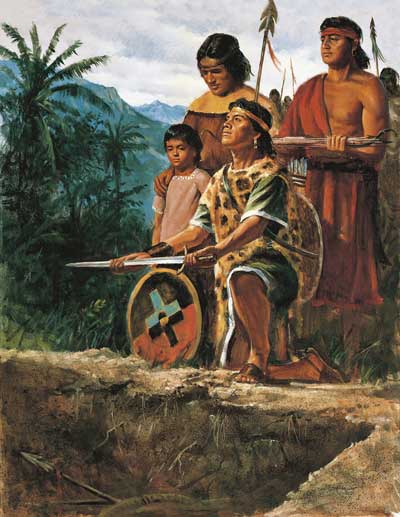

In the wake of the Anti-Nephi-Lehies’ conversion to the Gospel and newfound political affiliation with the Nephites (Alma 23),1 the Amulonites and the Amlicites,2 their former political allies, made preparations for war (Alma 24:1–2).3 The Anti-Nephi-Lehies, however, refused to take up arms, even in self-defense (v. 6). Instead, they buried their weapons deep into the earth as “a testimony to God, and also to men, that they never would use weapons again for the shedding of man’s blood” (vv. 17–18).

Given the setting of the assembled people making a covenant with God, Corbin Volluz concluded that “this text must be understood in a ceremonial context.”4 Dedication and termination ceremonies, representing the end of an old or the starting of a new way of life, are known in many cultures, and in Preclassic Mesoamerica these date from as early as 1500 BC. They often included burials of tools or other objects as a metaphor for sacrifice. This type of occasion would be fitting for the covenant and actions made by the Anti-Nephi-Lehies.5

As part of their new life going forward, the people began to live the law of Moses (Alma 25:15–16). Part of this law identified those who killed with instruments or weapons of iron, stone, and wood as “murderers” (Numbers 35:16–18). Thus, by getting rid of “all the weapons which were used for the shedding of man’s blood” (Alma 24:17), the Anti-Nephi-Lehi’s assured themselves and God that they would never again commit an unlawful, intentional murder.

On this occasion, King Anti-Nephi-Lehi gave a speech in which he repeated various forms of the term stain and also the words our swords seven times each.6 In addition, blood is repeated seven times in the narrative about the covenant.7 These repeated terms are tied tightly together: it is blood that stains swords, which are then made “bright” again through the cleansing power of the atonement (Alma 24:12–13, 15). If the swords were the Mesoamerican macuahuitl, this imagery could be even more powerful, since blood would literally stain and discolor the wooden shafts.8

The Why

It is possible that the symbolism of the number seven had been maintained over the years in Lamanite traditions, or it could have entered this covenantal ceremony from Ammon’s teachings based on the frequent use of the number seven in the plates of brass. Either way, it would have communicated to the God of Israel the seven-fold completeness of the commitment of these Ammonites to never again stain their swords with blood.

Ritual actions of the Mosaic law often employed sevenfold repetitions, as on the Day of Atonement with the ritual of sprinkling blood seven times upon the altar and the mercy seat in the temple (Leviticus 16:14–19, 27). Volluz reasoned:

The sevenfold repetition of these words in these five verses [in Alma] invokes the memory of the sevenfold blood sacrifices, dippings, and sprinklings that accompanied purification and cleansing rituals and covenants under the law of Moses, which these Ammonites were especially careful to keep as they looked forward to the coming of Christ (Alma 25:15).9

In the Anti-Nephi-Lehi narrative, blood is described as something that can be shed (Alma 24:17–18), something that stains (vv. 12–13, 15), and washes clean through atonement (v. 13). This language and the rhetorical repetition and interaction of stains, swords, and blood provides poignant atonement imagery. Three occurrences of stains appear in a context where the reader expects sins. They “repent[ed] sufficiently before God that he would take away [their] stains” (v. 11; cf. vv. 12, 15).10 God removed their “stains,” making their “swords … [to] become bright” (v. 12) and the stain of their swords was “washed bright through the blood of the Son of our great God” (v. 15).

Just as ritual blood sprinkling on the Day of Atonement symbolized the atoning blood of Christ,11 the blood-stained swords of the Anti-Nephi-Lehi’s became symbolic of their sin-stained souls. Just as their swords were described as washed clean and made bright, so too were their sins washed away by the infinite atonement of Jesus Christ, and their lives were now brightened by the eternal light of the everlasting gospel.

They so treasured the purity gained through the atonement, they refused to take any chance that it might be lost again. So, as Elder Richard G. Scott observed, “The now-faithful people chose to succumb to the sword rather than risk their spiritual lives by taking up arms.”12 All who repent and come unto Christ may likewise have the stains of sin removed and cherish the blessings and purity of being washed clean by the blood of the Lamb.

Further Reading

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does King Benjamin Emphasize the Blood of Christ? (Mosiah 4:2),” KnoWhy 82 (April 20, 2016).

Corbin Volluz, “A Study in Seven: Hebrew Numerology in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies Quarterly 53, no. 2 (2014): 57–83.

Elder Richard G. Scott, “Personal Strength through the Atonement of Jesus Christ,” Ensign, November 2013, 82–84.

- 1. On the political ties that were formed, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why did Converted Lamanites call Themselves Anti-Nephi-Lehis? (Alma 23:17),” KnoWhy 131 (June 28, 2016).

- 2. Evidence from the original and printer’s manuscripts suggests that the Amalekites were the Amlicites. See Book of Mormon Central, “How Were the Amlicites and the Amalekites Related? (Alma 2:11),” KnoWhy 109 (May 27, 2016). Also see Royal Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon: Part Three, Mosiah 17–Alma 20 (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2006), 1605–1609; J. Christopher Conkling, “Alma’s Enemies: The Case of the Lamanites, Amlicites, and Mysterious Amalekites,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 1 (2005): 108–117, 130–132.

- 3. To see these verses with “Amlicites” instead of “Amalekites,” see Royal Skousen, ed., The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 365.

- 4. Corbin Volluz, “A Study in Seven: Hebrew Numerology in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies Quarterly 53, no. 2 (2014): 81.

- 5. See Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 307–308. See also Jonathan B. Pagliaro, James F. Garber, and Travis W. Stanton, “Evaluating the Archaeological Signatures of Maya Ritual and Conflict, ” in Ancient Mesoamerican Warfare, ed. M. Kathryn Brown and Travis W. Stanton (Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMire Press, 2003), 75–89.

- 6. For stain: Alma 24:11, 12 (2x), 13 (2x), 15 (2x). For our swords: Alma 24:12 (2x), 13 (2x), 15 (2x), and 16

- 7. Alma 24:12, 13 (2x), 15, 17, 18 (2x). Volluz, “A Study in Seven,” 81, points out the repetition of stain and our swords, but not blood.

- 8. See William J. Hamblin and A. Brent Merrill, “Swords in the Book of Mormon,” in Warfare in the Book of Mormon, ed. Stephen D. Ricks and William J. Hamblin (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 342–343. Also see Matthew Roper, “On Cynics and Swords,” FARMS Review of Books 9, no. 1 (1997): 151–152; Matthew Roper, “Swords and ‘Cimeters’ in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 8, no. 1 (1999): 39.

- 9. Volluz, “A Study in Seven,” 81.

- 10. Skousen, The Earliest Text, 366.

- 11. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does King Benjamin Emphasize the Blood of Christ? (Mosiah 4:2),” KnoWhy 82 (April 20, 2016).

- 12. Elder Richard G. Scott, “Personal Strength through the Atonement of Jesus Christ,” Ensign, November 2013, 82.

Continue reading at the original source →