The Know

No other event had a greater impact on Alma’s life than the transformative three days he spent racked with torment after being rebuked by an angel.1 The themes of that experience permeate his sermons,2 and at least three different accounts of it survive in the Book of Mormon (Mosiah 27; Alma 36, 38). Detailed comparison of these accounts strongly suggests that all three are, in significant part, first person accounts from Alma himself.3 Of these accounts, Alma 36 stands out as the most complete and well-composed.

John W. Welch noted, “The abrupt antithetical parallelisms” of Alma’s original words in Mosiah 27:29–30, “have been rearranged into one masterfully crafted chiastic composition in Alma 36.”4 This repurposing of the spontaneous phrases spoken by the young Alma as he retold the story of his conversion to his son Helaman a number of years later offers strong evidence that the structure of Alma 36 was deliberate and purposeful.

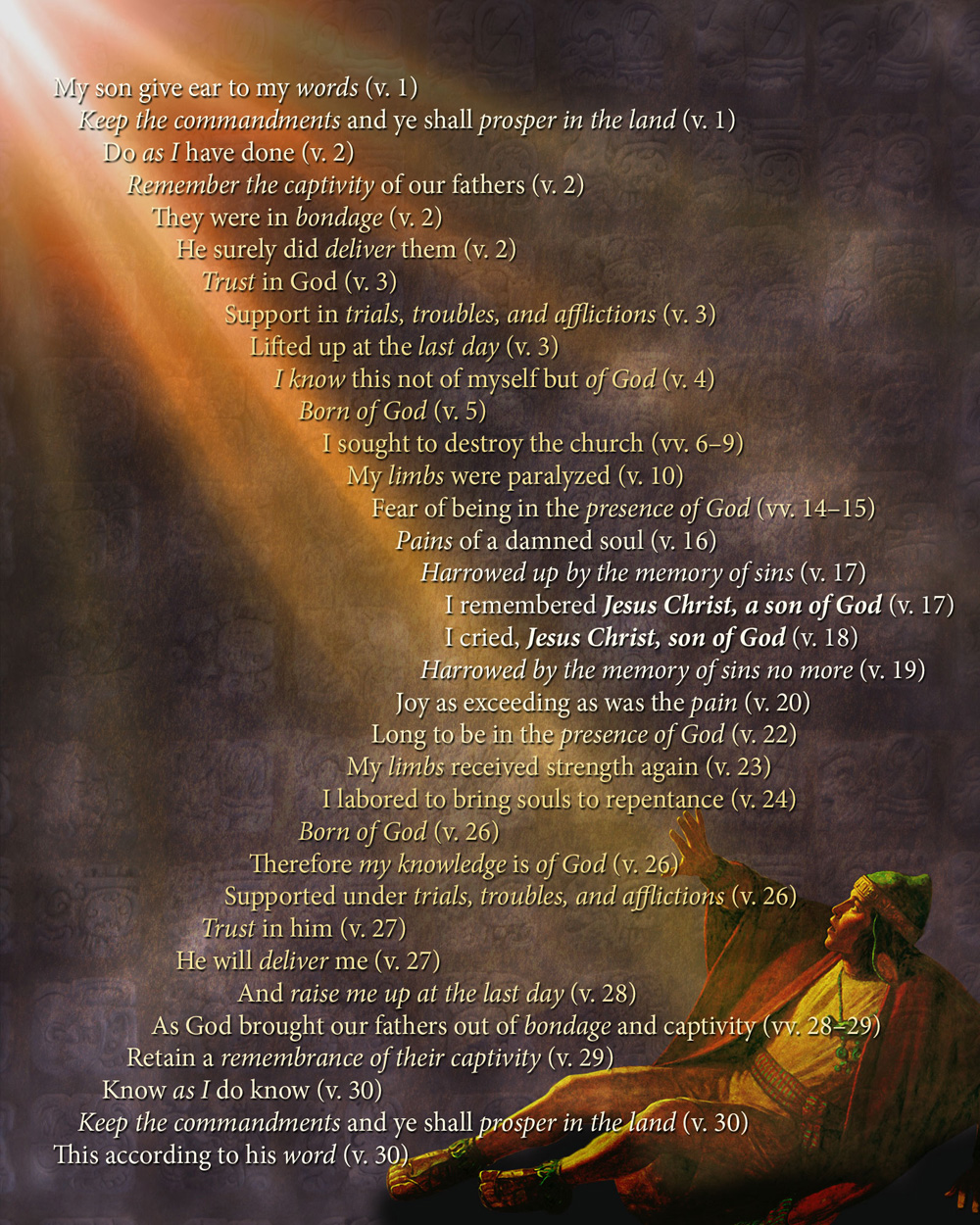

Welch, who discovered chiasmus in the Book of Mormon as a missionary in Germany in 1967,5 first published the chiastic structure of Alma 36 in 1969 (see chart).6 Since that time, the structure of Alma 36 has received continued attention and analysis, detailing not only the overall chiasm, but also laying out several substructures.7

Of interpretive importance, careful observers have found that the climax of a strong chiastic structure is usually found at its midpoint. As Nils Lund set forth, “The centre is always the turning point. . . . At the centre there is often a change in the trend of thought, and an antithetic idea is introduced, [which is a] shift at the centre. . . . Thus, the climax is at the centre, not at the end, where we should expect it.”8 This feature of a deliberately composed chiasm, clearly present in Alma 36, helps readers to discern the the key point of the whole passage.

Though some have questioned the absolute chiasticity of the account,9 both criteria-based evaluations and statistical analyses further indicate that the chiastic structure in Alma 36 is unlikely to be an accident.10 Welch concluded, “After evaluating hundreds of proposed chiasms in a wide variety of lengthy texts, I have found that only a few texts unmistakably rate as planned, successful chiasms. Alma 36 is one of the best.”11

The Why

Producing a well written, elegant chiasm is challenging and difficult. According Welch, “If an author uses chiasmus mechanically, it can produce rigid, stilted writing (a poor result from an author misusing or poorly implementing any artistic device).”12 This is not the case with Alma 36, which smoothly transitions from one point to the next until reaching its climatic center point and then effortlessly unwinding down the same path.13

Alma … does not simply stick a list of ideas together in one order and then awkwardly and slavishly retrace his steps through that list in the opposite order. His work has the markings of a skillful, painstaking writer, one completely comfortable with using this difficult mode of expression well.14

Grant Hardy noted, Alma’s “account moves from public to personal to private and then back again.”15 Throughout the whole account, Hardy noticed the remarkable detail that “God is present in every phase.” Hardy thus thought “the order and purposeful design of Alma 36 suggests a world in which God … is in control, where the lives of individuals fit into some overarching … plan.”16

Central to that plan is Jesus Christ and his atoning power. While Alma on some occasions placed emphasis on the angelic encounter,17 it was not the appearance of the angel that caused Alma’s change of heart. Indeed, the chiastic structure in Alma 36 eloquently and effectively guides the reader most centrally and emphatically toward Alma’s direct, personal encounter with Jesus Christ. Welch noted:

The structure of the chapter powerfully communicates Alma’s personal experience, for the central turning point of his conversion came precisely when he called upon the name of Jesus Christ and asked for mercy. Nothing was more important than this in Alma’s conversion—neither the appearance of the angel, nor the prayers of his father and the priests. Just as this was the turning point of Alma’s life, he makes it the center of this magnificent composition.18

The point of this remarkable literary structure underscores the dramatic turnaround in Alma’s life, answering most assuredly the question, why was Alma converted? That conversion occurred when he remembered his father speaking of “the coming of one Jesus Christ, a Son of God, to atone for the sins of the world,” which caused him to call out, “O Jesus, thou Son of God, have mercy on me, who am in the gall of bitterness, and am encircled about the by everlasting chains of death” (Alma 36:17–18).

From that turning point, the chiastic pattern takes on what Noel B. Reynolds termed a “reverse polarity between the parallel units of text.”19 While once “harrowed up by the memory of [his] many sins” (Alma 36:17), he was “harrowed up by the memory of [his] sins no more” (v. 19). Where once there was “the pains of a damned soul” (v. 16), there now a “soul … filled with joy as exceeding as was [the] pain!” (v. 20).

The reversal here proceeds out from the central point until Alma’s effort “to destroy the church of God” (Alma 36:6) is juxtaposed with his new, unceasing effort to “bring souls unto repentance” (v. 24). From this reversal, Welch reasoned, “The message is clear: Christ’s atonement and man’s responding sacrifice of a broken heart and willing mind are central to receiving forgiveness from God.”20

It is hard to imagine any literary form being used more effectively than this extended chiasm to articulate the transformative effect of the Atonement in the lives of individuals all around the world. Many have felt as Alma felt. As a result, Alma 36 naturally and powerfully resonates with readers everywhere.21 After reading Alma 36 with Welch, prominent biblical scholar David Noel Freedman remarked, “Mormons are very lucky. Their book is very beautiful.”22 After extensive study of Alma 36, Welch concluded:

This text ranks as one of the best uses of chiasmus one can imagine. It merits high acclaim and recognition. Despite its complexity, the meaning of the chapter is both simple and profound. Alma’s words are both inspired and inspiring, religious and literary, historical and timeless, clear yet complex—a text that deserves to be pondered for years to come.23

Further Reading

John W. Welch, “A Masterpiece: Alma 36,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1991), 114–131.

John W. Welch, “Chiasmus in Alma 36,” FARMS Preliminary Report (1989).

John W. Welch, “Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” in Book of Mormon Authorship: New Light on Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1982; reprint, FARMS, 1996), 33–52.

- 1. Alma’s experience is strikingly similar to the ordeals that Mesoamerican ritual specialists undergo in order to become healers and religious leaders. See Mark Alan Wright, “‘According to Their Language, unto Their Understanding’: The Cultural Context of Hierophanies and Theophanies in Latter-day Saint Canon,” Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 3 (2011): 58–64; Mark Alan Wright, “Nephite Daykeepers: Ritual Specialists in Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon,” in Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of the Expound Symposium, 14 May 2011, ed. Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks, and John S. Thompson (Salt Lake City and Orem, UT: Eborn Books and Interpreter Foundation, 2014), 247–252.

- 2. S. Kent Brown, “Alma’s Conversion: Reminiscences in His Sermons,” in The Book of Mormon: Alma, The Testimony of the Word, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 141–156; reprinted in S. Kent Brown, From Jerusalem to Zarahemla: Literary and Historical Studies of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1998), 113–127. Also see Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), 134–137.

- 3. John W. Welch, “Three Accounts of Alma’s Conversion,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 150–153; John W. Welch and J. Gregory Welch, Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching (Provo, UT: FARMS, 199), charts 106–107.

- 4. Welch, “Three Accounts of Alma’s Conversion,” 152.

- 5. See John W. Welch, “The Discovery of Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon: Forty Years Later,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 16, no. 2 (2007): 74–87, 99; John W. Welch, “Forty-Five Years of Chiasmus Conversations: Correspondence, Criteria, and Creativity,” presentation given at the 2012 FAIR Conference; J. Gregory Welch, “The Amazing True Story of How Chiasmus was Discovered in the Book of Mormon,” online video, September 1, 2015, online at bookofmormoncentral.org.

- 6. John W. Welch, “Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies 10, no. 3 (1969): 69–83. Also see John W. Welch, “Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” in Book of Mormon Authorship: New Light on Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1982; reprint, FARMS, 1996), 33–52; John W. Welch, “Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” in Chiasmus in Antiquity: Structures, Analysis, Exegesis, ed. John W. Welch (Provo, UT: Research Press, 1999), 198–210. Chart taken from Welch and Welch, Charting the Book of Mormon, 132.

- 7. See John W. Welch, “Chiasmus in Alma 36,” FARMS Preliminary Report (1989); John W. Welch, “A Masterpiece: Alma 36,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1991), 114–131; Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), 137–142; Noel B. Reynolds, “Rethinking Alma 36,” unpublished paper in our possession. The full structure of Alma 36 is also laid out in Donald W. Parry, ed., Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon: The Complete Text Reformatted (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2007), 318–321.

- 8. Nils Wilhelm Lund, Chiasmus in the New Testament (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1942), 40–41, 46.

- 9. See Earl M. Wunderli, “Criteria of Alma 36 as an Extended Chiasm,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 38, no. 4 (2005): 97–112; Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 4:495–497. Joseph M. Spencer, An Other Testament: On Typology, 2nd edition (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2016), 1–32 argues that while “the text appears to be structured as a chiastically framed narrative” (p. 4), only the beginning and end (vv. 1–5, 26–30) are chiastic, while the core (vv. 13–22) is guided by an entirely different structure.

- 10. For a criteria evaluation, see Welch, “A Masterpiece,” 129–130; Welch, “Chiasmus in Alma 36,” 26–35. For an explanation of criteria for judging a chiasm, see John W. Welch, “Criteria for Identifying and Evaluating the Presence of Chiasmus,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 4, no. 2 (1995): 1–14. Also see the “Criteria Chart,” at Chiasmus Resources, online at http://chiasmusresources.johnwwelchresources.com/. For statistical evaluation, see Boyd F. Edwards and Farrell W. Edwards, “Does Chiasmus Appear in the Book of Mormon by Chance?,” BYU Studies 43, no. 2 (2004): 103–130; Boyd F. Edwards and Farrell W. Edwards, “Response to Earl Wunderli’s ‘Critique of Alma 36 as an Extended Chiasm’,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 39, no. 3 (2006): 164–169.

- 11. Welch, “A Masterpiece,” 116.

- 12. Welch, “A Masterpiece,” 128.

- 13. Welch, “A Masterpiece,” 127–128; Welch, “Chiasmus in Alma 36,” 24–25.

- 14. Welch, “A Masterpiece,” 128.

- 15. Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 140.

- 16. Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 140–141.

- 17. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did the Angel Speak to Alma with a Voice of Thunder? (Mosiah 27:11),” KnoWhy 105 (May 23, 2015).

- 18. Welch, “A Masterpiece,” 118. Welch, “Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon” (1982), 51: “Chiasmus allows Alma to place the very turning point of his entire life exactly at the turning point of this chapter: Christ, because of the effects of the future atonement, belongs at the center of both. Compared with the abrupt antithetic parallelisms found in the recounting of this incident recorded in Mosiah 27, the chiasmus in Alma 36 is monumental and meaningful. The chiastic structure amplifies the significance of Alma’s conversion and the centrality of spiritual realities around which it turned.” Welch, “Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” (1999), 207: “it says much for Alma’s artistic sensitivities that he succeeds in placing the turning point of his life at the turning point of this chapter. Such effects, it would appear, do not occur without design.”

- 19. Reynolds, “Rethinking Alma 36,” 6.

- 20. Welch, “A Masterpiece,” 127.

- 21. In a similar way, another classic conversion story that has enjoyed very wide appeal is that of Jonah, who resisted the Lord’s call for him serve as a messenger of the gospel of repentance to the city of Nineveh. As has been recently observed, “the chiastic structure of the book of Jonah suggests that it was intentionally composed to center on Jonah’s exclamation of salvation (2:4–6), the physical midpoint as well as spiritual crux of this text.” See David Randall Scott, “The Book of Jonah: Foreshadowings of Jesus as the Christ,” BYU Studies Quarterly 53, no. 3 (2014): 173–174.

- 22. As quoted in John W. Welch, “What Does Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon Prove?” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited: The Evidence for Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 206.

- 23. Welch, “A Masterpiece,” 131.

Continue reading at the original source →