The Know

Just before the so-called “war chapters” of the book of Alma (Alma 45–62) is the account of a clash between the Nephite and Lamanite military commanders Moroni and Zerahemnah, respectively (Alma 43–44). After affirming that the Nephites did “not desire to be men of blood” (Alma 44:1), Moroni commanded their foe “in the name of that all-powerful God” (v. 5) to “deliver up [their] weapons of war unto” the victorious Nephites (v. 6). If Zerahemnah would do this his life and the lives of his men would be spared (v. 6).

Zerahemnah’s response was terse and adamant: “Behold, here are our weapons of war; we will deliver them up unto you, but we will not suffer ourselves to take an oath unto you, which we know that we shall break, and also our children; but take our weapons of war, and suffer that we may depart into the wilderness; otherwise we will retain our swords, and we will perish or conquer” (Alma 44:8). Believing he had been defeated through Nephite ingenuity rather than divine intervention, Zerahemnah was willing to cede the immediate battle but refused perpetual surrender (v. 9).

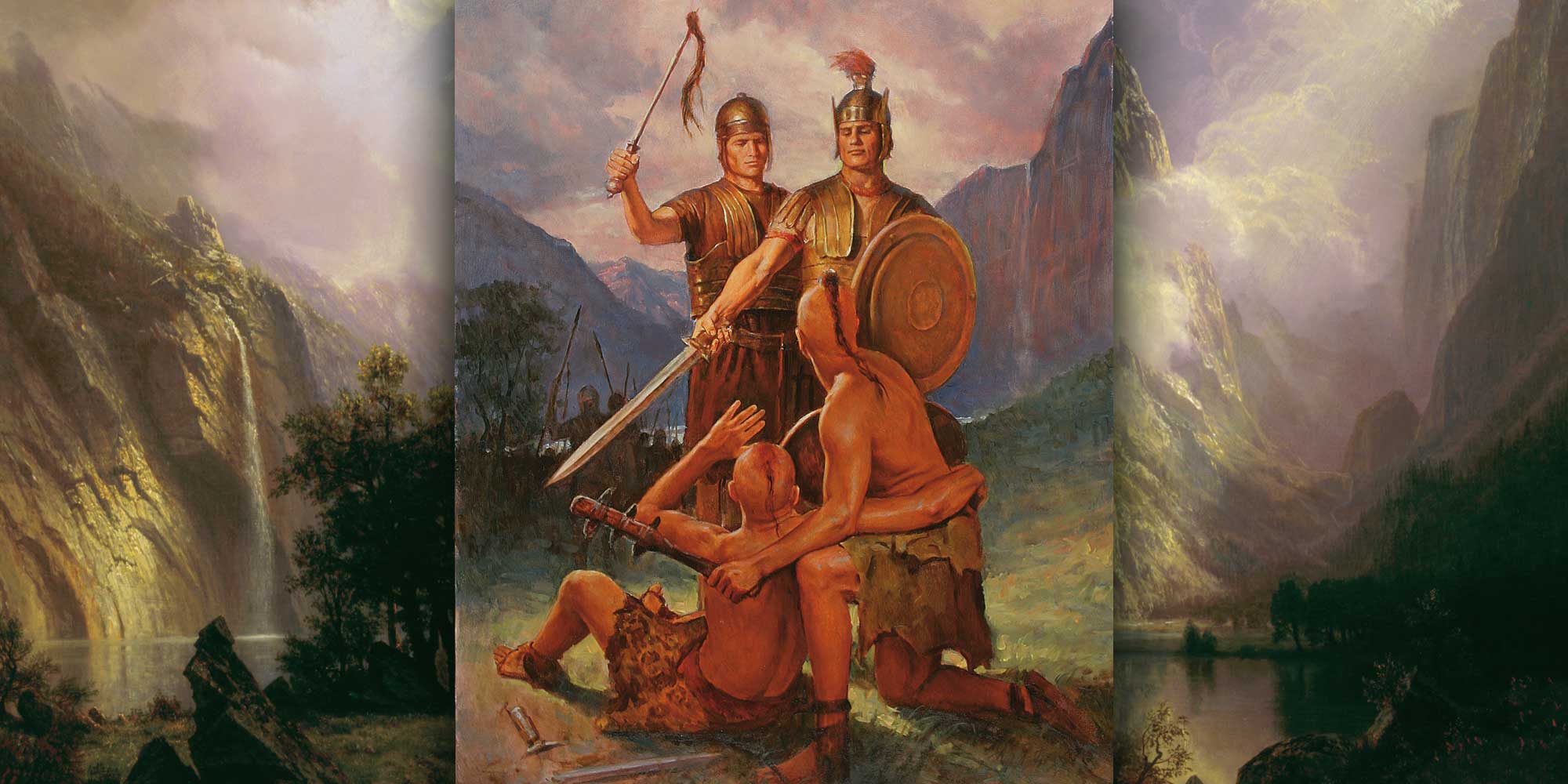

After another round of negotiations (Alma 44:10–11), Zerahemnah suddenly attacked when Moroni briefly let his guard down. However, the Lamanite commander was halted when “one of Moroni’s soldiers . . . smote Zerahemnah that he took off his scalp and it fell to the earth” (v. 12). Immediately thereafter.

the soldier who stood by, who smote off the scalp of Zerahemnah, took up the scalp from off the ground by the hair, and laid it upon the point of his sword, and stretched it forth unto them, saying unto them with a loud voice: Even as this scalp has fallen to the earth, which is the scalp of your chief, so shall ye fall to the earth except ye will deliver up your weapons of war and depart with a covenant of peace. (Alma 44:13–14)

Utterly defeated, and moments away from death, Zerahemnah finally covenanted with Moroni and withdrew what was left of his now unarmed and humiliated army, never to be heard of again (Alma 44:19–24).

It is important to note that Moroni invoked the name of God in the brief covenant-making ceremony he enacted with Zerahemnah (Alma 44:4). Invoking the name of a deity to witness and ratify a covenant or oath was standard procedure in ancient Near Eastern oath-making ceremonies. The understanding anciently was that if a party failed to keep the covenant, then that party would face divine retribution. This might explain why Zerahemnah initially refused to make an oath he knew he couldn’t (or wouldn’t) keep. He may have feared God at least enough to anticipate divine wrath should he fail to keep the covenant, even if he disbelieved it was God who granted the Nephites victory (Alma 44:9).

Whatever the case on Zerahemnah’s part, the subsequent action of Moroni’s soldier who lifted up the Lamanite commander’s scalp makes perfect sense from an ancient perspective. Scholars have identified a pattern of oath-making in the ancient Near East that involves what is commonly called a simile curse.1 As found in Hittite and Semitic cultures, simile curses involved one party in a covenant forewarning the precise penalties that should befall the other parties if they were ever to break the pact.

These penalties were framed in the form of a simile: “If so-and-so does not keep this covenant, then may he be destroyed just or even as this object shall be destroyed.” Simile curses were sometimes accompanied by the party giving the terms dramatically destroying some kind of object, animal, or figure that symbolized the doomed party.

For example, an eighth century BC Aramaic treaty contains a clear example of a simile curse. “Just as this wax is burned by fire, so shall Mati[el be burned by fi]re. Just as (this) bow and these arrows are broken, so may Anahita and Hadad break [the bow of Matiel] and the bow of his nobles. And just as a man of wax is blinded, so may Mati[el] be blinded.”2

The Hebrew Bible also contains an example of a simile curse. In 1 Kings 14 the prophet Ahijah was commanded by God to foretell divine retribution for the wicked king Jeroboam. “Therefore, behold, I will bring evil upon the house of Jeroboam,” God promised, “and will take away the remnant of the house of Jeroboam, as a man taketh away dung, till it be all gone” (1 Kings 14:10; compare 2 Kings 21:13). Simile curses are found in a number of Hittite texts, such as a series of oaths Hittite soldiers made as part of their military service.3 Curses against those who break or alter the terms of suzerain-vassal treaties are also included in some Hittite texts written on bronze plates.4

The Why

As explored in a previous KnoWhy, the nature of oaths and oath-making in the Book of Mormon closely follows an ancient Near Eastern pattern.5 This includes a sometimes life-or-death seriousness when it comes to making and keeping covenants and oaths. A close reading of Alma 44 reveals that Moroni’s interaction with Zerahemnah followed the same pattern.

Latter-day Saint scholars have noted that the pronouncement of the Nephite soldier who scapled Zerahemnah follows the simile curse formula almost perfectly: “Even as this scalp has fallen to the earth, which is the scalp of your chief, so shall ye fall to the earth except ye will deliver up your weapons of war and depart with a covenant of peace” (Alma 44:14).6 From an ancient perspective this simile curse would have greatly reinforced the life-and-death seriousness of the covenant Moroni had commanded Zerahemnah to enter, and would have given Zerahemnah even more reason not to agree with Moroni’s demand without absolute certainty of keeping it.

The elements of Alma 44 combine to show that both the Nephites and Lamanites, including even the wrathful Zerahemnah, respected the seriousness of oaths, especially oaths sworn in God’s name. This in turn demonstrates “the rich complexity of the Book of Mormon” as well as its ancient provenance.7

Further Reading

RoseAnn Benson and Stephen D. Ricks, “Treaties and Covenants: Ancient Near Eastern Legal Terminology in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 1 (2005): 48–61, 128–29.

Mark J. Morrise, “Simile Curses in the Ancient Near East, Old Testament, and Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2, no. 1 (1993): 124–138.

Terrence L. Szink, “Oath of Allegiance in the Book of Mormon,” in Warfare in the Book of Mormon, ed. Stephen D. Ricks and William J. Hamblin (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 35–45

- 1. See generally Delbert R. Hillers, Treaty–Curses and the Old Testament Prophets, Biblica et Orientalia 16 (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1964); Noel Weeks, Admonition and Curse: The Ancient Near Eastern Treaty/Covenant Form as a Problem in Inter-Cultural Relationships, The Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 407 (London: T&T Clark, 2004); Anne Marie Kitz, “An Oath, It’s Curse and Anointing Ritual,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 124, no. 2 (April–June 2004): 315–321; “Effective Simile and Effective Act: Psalm 109, Numbers 5, and KUB 26,” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 69, no. 3 (July 2007): 440–456; Mary R. Bachvarova, “Oath and Allusion in Alcaeus FR. 129,” in Horkos: The Oath in Greek Society, ed. Alan H. Sommerstein and Judith Fletcher (Exeter: Bristol Phoenix Press, 2007), 179–188.

- 2. Joseph A. Fitzmyer, “The Aramaic Inscriptions of Sefire I and II,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 81, no. 3 (August–September 1961): 185. Brackets indicate instances where the original text has been broken in the manuscript, and so the translation has been restored by the translator. Compare also the treaty between Ashurnirari V and Mati’ilu in James B. Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures, rev. ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), 210–212.

- 3. These texts, which contain multiple explicit simile curses for soldiers who fail their military duties, are very interesting in light of the military context of Alma 44. See Billie Jean Collins, “The First Soldiers’ Oath” and “The Second Soldier’s Oath,” in The Context of Scripture, Volume I: Canonical Compositions from the Biblical World, ed. William W. Halo (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 165–168.

- 4. See Weeks, Admonition and Curse, 75–77; Jared L. Miller, trans., Royal Hittite Inscriptions and Related Administrative Texts, ed. Mauro Giorgieri (Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013), 3.

- 5. Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did the Lamanites Break Their Treaty with King Limhi? (Mosiah 20:18),” KnoWhy 98 (May 12, 2016). Compare RoseAnn Benson and Stephen D. Ricks, “Treaties and Covenants: Ancient Near Eastern Legal Terminology in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 1 (2005): 48–61, 128–29.

- 6. See Terrence L. Szink, “Oath of Allegiance in the Book of Mormon,” in Warfare in the Book of Mormon, ed. Stephen D. Ricks and William J. Hamblin (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 35–45; Mark J. Morrise, “Simile Curses in the Ancient Near East, Old Testament, and Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2, no. 1 (1993): 124–138; Donald W. Parry, “Hebraisms and Other Ancient Peculiarities in the Book of Mormon,” in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2002), 156–159.

- 7. Benson and Ricks, “Treaties and Covenants,” 61.

Continue reading at the original source →