The Know

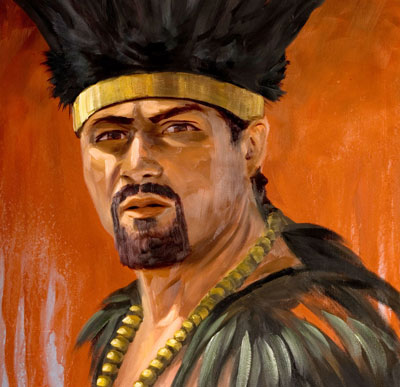

The Nephite defector Amalickiah is infamous for his treachery, fraud, and deceit. A descendant of Zoram (Alma 49:25; 54:23), Amalickiah “used flattery and played on the ambitions of others to obtain a substantial following” before eventually assassinating the Lamanite king and launching war on the Nephites (Alma 46–50).1 Amalickiah met his end when the Nephite warrior Teancum snuck into his camp and “put a javelin to his heart” while he slept (Alma 51:34).2

Amalickiah’s legacy did not die with him, however. Amalickiah’s brother Ammoron succeeded him as king of the Lamanites and did not hesitate in continuing his fallen brother’s warfare against the Nephites (Alma 52). Like his brother, Ammoron had no love for his former brethren, and demanded no less than total surrender or annihilation. “We will wage a war which shall be eternal, either to the subjecting the Nephites to our authority or to their eternal extinction,” boasted Ammoron (Alma 54:20).

Ammoron’s hatred for the Nephites also ran on a deeply personal level. In a heated letter to Moroni, the new Lamanite king vowed,

“I am Ammoron, the king of the Lamanites; I am the brother of Amalickiah whom ye have murdered. Behold, I will avenge his blood upon you, yea, and I will come upon you with my armies for I fear not your threatenings” (Alma 54:16).

Ironically, Amalickiah had sworn that he would drink the blood of Moroni (Alma 49:27; 51:9), but now it was Amalickiah’s blood that needed to be avenged.

Besides feeling personally obligated to avenge the blood of his brother, Ammoron went back to the origins of tribal conflict in the earliest days of the Nephite–Lamanite split. “For behold, your fathers did wrong their brethren, insomuch that they did rob them of their right to the government when it rightly belonged unto them” (Alma 54:17). “I am a bold Lamanite,” declared Ammoron, a former Zoramite, thus making it clear he had switched sides, adopting a new political and cultural identity (v. 54).

The dynamics fueling Ammoron’s worldview and objectives are complex. At a most basic level, this is a rather obvious example of tribalism and ethnic tension. While political aspirations were undoubtedly tied up in Ammoron’s declaration, it is important to note that he appealed to a deeply rooted tribal or clan rivalry as the motivation for his political goals. In perpetuating this tribal antagonism, Ammoron promoted an ideology fundamentally at odds with the egalitarian and anti-tribal ideals of Nephite prophets (cf. 2 Nephi 26:33; Mosiah 4:19; 4 Nephi 1:2, 17).3

An additional motivating factor for Ammoron may be related to the Hebrew judicial concept of “blood vengeance.” In a world with no real equivalent to modern law enforcement, “one of the most important clan duties” in many ancient cultures was “for the nearest of kin to hunt down and carry out the death-penalty on a person that had slain a member of the sept or family.”4 Ancient Hebrew law allowed for this, granting the legal right and duty for a kinsman to avenge the blood of a murdered family or clan member (Exodus 21:12–14; Numbers 35:16–28; Deuteronomy 19:4–13).5

This avenger of blood is called a goel in biblical Hebrew. Conventionally translated as “redeemer,”6 one of the responsibilities of being an avenging kinsman (a goel) was to bring about justice, rectifying the intentional and hateful murder of a near family member by killing the murderer or a substitute.7 At the same time, one suspected of wrongful homicide had the right to flee to a city of refuge, where a disinterested body of elders and Levites would hear the case (Numbers 35:9–24; Deuteronomy 4:41–44).

Extending this legal procedure into the theological realm, Jehovah was, naturally, considered the divine goel (redeemer, avenger) of Israel as a whole (Exodus 6:6; 15:13; Psalm 74:2; 94). He was expected to avenge Israel’s blood shed by her physical and spiritual enemies and also to redeem Israel or buy her back from bondage, slavery, or debt servitude.

The language in Alma 54 surely suggests that Ammoron was familiar with this underlying institution of blood redemption. He saw himself as acting in a redemptive capacity. His threat to Moroni that he would specifically “avenge [his brother Amalickiah’s] blood upon you” invokes and captures the thrust of the blood vengeance mechanism stemming from the earliest days of ancient Israelite history.

Recalling that both Amalickiah and Ammoron were former Nephites, it makes sense that Ammoron would invoke the concept of Hebraic blood vengeance in his threat against Moroni. Moreover, since the Zoramites rejected the law of Moses (Alma 31:9), it is not surprising that Ammoron failed to extend to Moroni the protections of refuge and a trial that the law of Moses would have guaranteed to him.

The Why

In a straightforward reaction, Ammoron threatened to hold Moroni personally accountable for the death of his brother, Amalickiah. Teancum was one of Moroni’s warriors, and although he apparently acted on his own initiative, Ammoron would have naturally invoked his traditional rights and duties to avenge the death of his brother. He tried to do this by putting Moroni on notice that he was a hunted man.

Yet Ammoron himself acted rashly in making this threat. His motives were not based in measured legal steps. Why, for example, did he not seek the blood of the slayer, Teancum, who was still alive? The answer to this question probably lies in Ammoron’s desire to escalate the situation, using the death of King Amalickiah as justifying a call for the death of a higher ranking Nephite, like Moroni. This, however, was not a call for legal justice. Ammoron, assuming unto himself the role of divine avenger, would hardly have allowed Moroni to flee to an altar of refuge for protection and justice.8

Ammoron’s reaction typifies one more way in which the war chapters in the book of Alma are composed as a portrait of stark opposites. The righteous heroes Moroni and Helaman stand in contrast with the villains Amalickiah and Ammoron. Where Moroni was honorable, just, and righteous (Alma 48:17–18), Amalickiah was power-hungry, treasonous, and deceitful (Alma 46:4–5; 47:30, 35). Where Moroni treated his enemies nobly (Alma 44:1–7), Ammoron treated his enemies spitefully, and in this case vindictively (Alma 54:16–24). This point was included by Mormon in his final record in order to paint for modern readers a clear picture of what good and bad leaders look like.

By studying Ammoron’s personality, including his literal thirst for blood and vengeance, readers of the Book of Mormon are also warned to avoid allowing past grievances and old wounds to consume one with hatred and malice. Had Ammoron sought the true Redeemer’s way of reconciliation instead of raw vengeance, it’s very likely that thousands of lives, including his own (Alma 62:35–36), would have been spared from years of bloody and senseless conflict.

Further Reading

Richard McClendon, “Captain Moroni’s Wartime Strategies: An Application for the Spiritual Battles of Our Day,” Religious Educator 3, no. 3 (2002): 99–114.

Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 4:689–694.

- 1. Clyde James Williams, “Amalickiah,” in Book of Mormon Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2003), 45.

- 2. Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Teancum Slay Amalickiah on New Year’s Eve? (Alma 51:37),” KnoWhy 160 (August 8, 2016).

- 3. See Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 188–189.

- 4. Morris Jastrow, Jr., “Avenger of Blood,” in Jewish Encyclopedia, online at jewishencyclopedia.com; A “sept” is an archaic term synonymous with “clan” or “family.” Compare “Blood-Avenger,” in Encyclopedia Judaica, online at jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- 5. Ze’ev W. Falk, Hebrew Law in Biblical Times (Provo, UT and Winona Lake, IN: BYU Press and Eisenbrauns, 2001), 72.

- 6. Ludwig Koehler and Walter Baumgartner, The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament, 2 vols. (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 1:169.

- 7. David Ewert, “Avenger of Blood,” in The Oxford Companion to the Bible, ed. Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1993), 68; Bernhard W. Anderson, Understanding the Old Testament, abridged 4th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice–Hall, 1998), 430–431. Other duties of a goel included redeeming property, including family sold into debt slavery (Leviticus 25:25, 47–55; Jeremiah 32:6–12), and marrying the widow of a close family member (Deuteronomy 25:5–10; Ruth 3–4).

- 8. For altars as places of refuge, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did the People of Sidom Go to the Altar for Deliverance? (Alma 15:17),” KnoWhy 122 (June 15, 2016).

Continue reading at the original source →