The Know

After delivering the important prophecy concerning the signs which would herald Christ’s birth,1 Samuel the Lamanite explained that he was preaching among the Nephites that they might “know of the coming of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the Father of heaven and of earth, the Creator of all things from the beginning; and that ye might know of the signs of his coming, to the intent that ye might believe on his name” (Helaman 14:12, emphasis added).

The lengthy name-title of Christ contained in this verse is a verbatim quote from King Benjamin‘s prophecy concerning Christ’s birth. John W. Welch has noted, “The twenty-one words in italics appear to be standard Nephite religious terminology derived from the words given to Benjamin by an angel from God: ‘He shall be called Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the Father of heaven and of earth, the Creator of all things from the beginning’” (Mosiah 3:8).2

Moreover, this quotation is not the only reference to an earlier prophet found in Samuel’s prophecies. Contributions from several scholars demonstrate that Samuel’s prophecies—when looked at in their entirety—significantly relied on a variety of prior prophetic teachings, biblical phrases, and prophetic speech patterns.

S. Kent Brown, for example, found that Samuel’s prophecies contain poetic laments which noticeably “mirror traits found in Hebrew poetry.”3 Donald W. Parry has noted, “Six prophetic speech forms” are “present in Samuel’s speech.”4 Quinten Barney has argued that Samuel’s prophecy drew “heavily upon the words of Zenos as he prophesied concerning the death of Christ.”5 And according to Shon Hopkin and John Hilton III,

Samuel’s use of selected biblical phrases—“saith the Lord,” “Lord of Hosts,” “signs and wonders,” and “anger of the Lord” being “kindled”—in his discourse is consistently found at a higher frequency than for any other speaker in the Book of Mormon (besides biblical authors quoted in the Book of Mormon).6

The Why

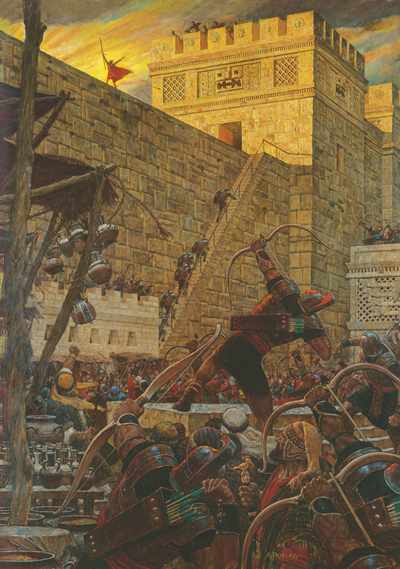

Although previous Lamanite missionaries had success preaching in Zarahemla a few years earlier (see Helaman 6:4–5), the Nephites were not as humble and teachable when Samuel, as an excluded visitor, spoke to them from the walls of that very city. Recognizing that they viewed him as an outsider, Samuel declared, “And now, because I am a Lamanite, and have spoken unto you the words which the Lord hath commanded me … ye are angry with me and do seek to destroy me” (Helaman 14:10).

Thus, in explaining Samuel’s significant use of biblical language, Hopkin and Hilton suggested, “It may be that as an ‘outsider’ Samuel sought to bolster his authority by using language similar to that found on the brass plates.”7 Along a similar line of thought, Samuel’s use of various traditional prophetic speech forms is evidence of his conscious desire to speak in a voice that, according to Parry, was “indicative of prophetic authority and prerogative.”8 These modes of expression gave his words a ring of power and truth.

It is also likely that Samuel’s reliance on scriptural language and concepts was intended to evoke certain themes or ideas which were immediately relevant to his own prophecies. For example, Samuel’s quotation of the lengthy name-title of Christ in Mosiah 3:8 could have helped his Nephite listeners recall that Christ’s coming had been prophesied by King Benjamin over a century earlier (see Mosiah 3:5–10).

They would also have remembered that this particular formulaic name had been given to their predecessors as part of an enduring covenant, in order to distinguish them from all other people (see Mosiah 1:11; 5:7–10). Samuel’s utterance of that holy covenantal name may well have surprised and even enraged his hostile listeners.

After having identified seven distinct literary sections in King Benjamin’s famous speech, John W. Welch noted, “The all-important sacred name is given at the very center of section 3 (see Mosiah 3:8), and the crucial terms on which the efficacy of the atonement depend are stated at the precise center of section 4 (Mosiah 3:18–19).”9 Thus the central importance of this sacred name-title likely held deep religious significance to the Nephites in Zarahemla, whose ancestors unitedly centered their lives on Jesus Christ and covenanted to become His sons and daughters through His atoning sacrifice. Echoing Benjamin’s rhetorical placement of this name at the center of his coronation speech, Samuel placed Christ’s special name-title near the midpoint of his own prophetic judgment speech.

Like Samuel, modern readers of the Book of Mormon can greatly benefit from studying, memorizing, and using the sacred language contained in the canon of LDS scripture.10 Quoting prophetic language readily lends authority and power to applicable teachings of central importance. Elder Richard G. Scott has taught,

The scriptures provide the strength of authority to our declarations when they are cited correctly. They can become stalwart friends that are not limited by geography or calendar. They are always available when needed. Their use provides a foundation of truth that can be awakened by the Holy Ghost. Learning, pondering, searching, and memorizing scriptures is like filling a filing cabinet with friends, values, and truths that can be called upon anytime, anywhere in the world.11

Further Reading

Shon Hopkin and John Hilton III, “Samuel’s Reliance on Biblical Language,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 24 (2015): 31–52.

S. Kent Brown, “The Prophetic Laments of Samuel the Lamanite,” in From Jerusalem to Zarahemla: Literary and Historical Studies of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1998), 163–180.

John W. Welch, “Textual Consistency,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 21–23.

Donald W. Parry, “‘Thus Saith the Lord’: Prophetic Language in Samuel’s Speech,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 1, no. 1 (1992): 181–183.

- 1. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Samuel Make Such Chronologically Precise Prophecies? (Helaman 13:5),” KnoWhy 184 (September 8, 2016).

- 2. John W. Welch, “Textual Consistency,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 22. See also, John W. Welch and J. Gregory Welch, Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching, (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), chart 105; John W. Welch and Stephen D. Ricks, eds. “Appendix: Complete Text of Benjamin's Speech with Notes and Comments,” in King Benjamin’s Speech: “That Ye May Learn Widsom” (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 549 Although there is a small discrepancy between these verses in the current (2013) LDS edition of the Book of Mormon, evidence from the Printer’s Manuscript indicates that they were precisely identical in the original text. See Royal Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon, Part Two: 2 Nephi 11 – Mosiah 16, The Book of Mormon Critical Text Project, Volume 4 (Provo, UT: FARMS and Brigham Young University, 2014), 1167–1168. See also Royal Skousen, “Restoring the Original Text of the Book of Mormon,” a presentation given at the 2010 FairMormon conference, online at fairmormon.org: “Interestingly, in Mosiah 3:8, the 1830 typesetter accidentally deleted the preposition of before the noun earth, giving ‘the Father of heaven and earth’ rather than the correct ‘the Father of heaven and of earth.’”

- 3. S. Kent Brown, “The Prophetic Laments of Samuel the Lamanite,” in From Jerusalem to Zarahemla: Literary and Historical Studies of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1998), 141.

- 4. Donald W. Parry, “‘Thus Saith the Lord’: Prophetic Language in Samuel’s Speech,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 1, no. 1 (1992): 183. Parry labeled the six prophetic forms as (1) the messenger formula, (2) the proclamation formula, (3) the oath formula, (4) the woe oracle, (5) the announcement formula, and (6) the revelation formula. (pp. 181–183).

- 5. Quinten Barney, “Samuel the Lamanite, Christ, and Zenos: A Study of Intertextuality,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 18 (2016): 168.

- 6. Shon Hopkin and John Hilton III, “Samuel’s Reliance on Biblical Language,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 24 (2015): 50.

- 7. Hopkin and Hilton, “Samuel’s Biblical Language,” 51.

- 8. Parry, “Thus Saith the Lord,” 183.

- 9. John W. Welch, “Benjamin's Speech: A Masterful Oration,” in King Benjamin’s Speech, 69.

- 10. Modern prophets also frequently use prophetic language. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why do Certain ‘Treasured Words’ Appear So Repeatedly in General Conference Talks? (2 Nephi 25:26),” KnoWhy 69 (April 2, 2016).

- 11. Richard G. Scott, “The Power of Scripture,” Ensign, November 2011, 6, online at lds.org.

Continue reading at the original source →