The Know

After briefly reporting on 24 continuous years of war and wickedness, Mormon said that the Nephites entered into a treaty with the Lamanites in the 350th year (Mormon 2:28).1 The terms of the treaty required the Nephites to forfeit all their territory in the land southward (v. 29), but it brought peace for ten full years in return (Mormon 3:1).

Assuming that the Nephites festival schedule reset when they started counting their years from Christ’s birth, this would have been a jubilee year.2 The jubilee year was an additional sabbatical year observed at the end of the seventh seven-year sabbatical period.3

According Robin J. DeWitt Knauth, “The Year of Jubilee … is the last layer in the extension of the Sabbath principle.”4 Being the pinnacle of the sabbatical system, the jubilee year came every fifty years.5 It is easy to imagine that a people who saw significance in calendrical cycles of seven would surely have noticed that this jubilee year in the 350th year was not just any jubilee—it was the seventh jubilee since the birth of Christ (350 being 7 x 50).6

Given the decadence and wickedness among both the Nephites and the Lamanites, it is hard to say if the symbolic importance of that year was widely recognized.7 Mormon, no doubt, was aware, and as the Chief Captain of the Nephite armies, he was probably instrumental in negotiating the terms and timing of the treaty.

Resting the land was central to both the jubilee law in general and to this treaty in particular. The jubilee was intended to be “a year of ‘rest’ for the land.” It was also a time when “land was to be restored to its original inherited line of ownership.”8

It therefore seems significant that at a time when land was supposed to be restored to its proper owner, large portions of Nephite and Lamanite lands were reallocated under the terms of this ten-year treaty, as they “did get the lands of their inheritance divided” (Mormon 2:28). Any Nephites who still celebrated the jubilee could not have missed the significance: in the Lord’s eyes, they were no longer the proper owners of any land south of the narrow neck.

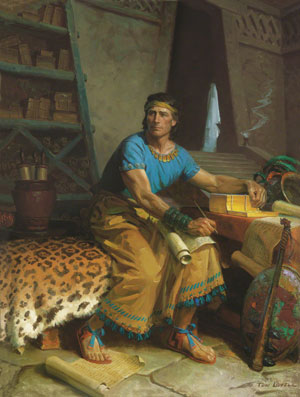

This reality probably wasn’t what Mormon would have hoped for in an ideal world, though he still likely welcomed the respite from combat that this extended jubilee season and treaty afforded. Mormon had taken command of the Nephite armies in his mid-teens (Mormon 2:2). He was now 40 years old, and battle worn after spending the better part of his life at war. Somewhere amid all the warfare and wickedness, Mormon must have found time to marry and father a son, Moroni. As the 350th year approached, he was likely eager to celebrate the jubilee season in peace with his family and other righteous followers.

The extended period of peace also afforded him other opportunities. For one, Mormon took advantage of the time to preach repentance unto the people, although it was to no avail (Mormon 3:2–3). It was probably during this time that Mormon wrote his epistle on faith, hope, and charity (Moroni 7), and also did the bulk of his work on the Nephite record, exploring the vast historical archive with which he had been entrusted, formulating the narrative he wanted to tell, and abridging and condensing that material into much of the Book of Mormon.

Moroni was probably a teenager during this time of peace, working under his father as an apprentice, learning the history of his people, and preparing for his role as the final Nephite record keeper and abridger. Given that Mormon was busy commanding the armies before the treaty, and Mormon and Moroni would both become embroiled again in war after the peace treaty expired, these were likely important, formative years for Moroni.

The Why

This ten-year treaty is a subtle detail, considering how rapidly Mormon passed over those years. The casual Book of Mormon reader can easily feel overwhelmed by the horrific accounts of war and wonder how Mormon, the leading military commander, would have had time to write such an extensive record of his people’s history.

The treaty provided an important—perhaps even essential—window of opportunity for Mormon to focus on his record keeping. Given the importance of the Book of Mormon in inspiring millions to come unto Christ, the Lord Himself may have been instrumental in bringing about this vital period of peace.

The treaty was also a testament to the good that righteous leaders can do, even in times of wickedness. As commander of the army, Mormon managed to bring peace to his people for ten full years—and at an important juncture in their history, namely the seventh jubilee since the coming of Christ. Though the people ultimately failed to take advantage of the opportunity to repent that this period of peace afforded them, it would be a mistake to dismiss it as a failure.

Although the peace did not last, in the face of perpetual war and total annihilation, to obtain a full decade of peace was a major accomplishment. No doubt it served as a blessing that strengthened Mormon’s people. The efforts of Mormon and potentially other righteous Nephite leaders involved in the negotiations should not be devalued, as they underscore the unremitting importance of choosing righteous leaders.

The timing—in the seventh jubilee year—was also significant. The jubilee year was a time of peace, rest, prosperity, forgiveness, and blessings.9 For their final jubilee before their complete destruction, the Nephites were granted an extended period of peace. Yet that peace came at the cost of all their territory in the land southward. The loss of land at a time when the land should be redeemed should serve as a powerful warning for modern day readers: just as the Nephites lost their land, so can mighty nations of today fall if they turn away from God and succumb to evil.

Perhaps most impressively, the treaty was also evidence of the Lord’s mercy. Despite the Nephites’ wickedness and their prophesied fate of destruction drawing nearer, it was not too late for them to change course. In this special jubilee year, the Lord “had spared them, and granted unto them a chance for repentance” (Mormon 3:3) and thereby obtain forgiveness.

Unfortunately, “the people failed to recognize that the period of peace they had experienced had come to them … as a merciful blessing from God to give them an opportunity to repent.”10 Today, even as the world drifts further away from the Lord’s standards, the opportunity for individuals and society as a whole to repent and change course is not lost, but time may be growing short.

Further Reading

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Alma Wish to Speak ‘With the Trump of God’? (Alma 29:1),” KnoWhy 136 (July 5, 2016).

John W. Welch and J. Gregory Welch, “Benjamin’s Themes Related to Sabbatical and Jubilee Years,” in Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), chart 91.

Terrence L. Szink and John W. Welch, “King Benjamin’s Speech in the Context of Ancient Israelite Festivals,” in King Benjamin’s Speech: “That Ye May Learn Wisdom”, ed. John W. Welch and Stephen D. Ricks (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 193–199.

- 1. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Mormon Write So Little About His Own Time Period? (Mormon 2:18)” KnoWhy 227 (November 9, 2016).

- 2. For discussion of the Jubilee in the Book of Mormon, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Alma Wish to Speak ‘With the Trump of God’? (Alma 29:1),” KnoWhy 136 (July 5, 2016).

- 3. See Robin J. DeWitt Knauth, “Sabbatical Year,” in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, ed. David Noel Freedman (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2003), 1147.

- 4. Robin J. DeWitt Knauth, “Jubilee, Year of,” in Eerdmans Dictionary, 743.

- 5. Knauth, “Jubilee, Year of,” 743 defined the Jubilee as the “50th year in a series of seven Sabbatical Years.” However, there is some ambiguity as to whether the jubilee was the 49th year (the seventh sabbatical year) or the 50th. Christopher J. H. Wright, “Jubilee, Year of,” in Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman, 6 vols. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992), 3: 1025, explained: “Lev 25:8–10 specifies it as the 50th year, though some scholars believe it may have been actually the 49th—i.e., the 7th Sabbatical Year.” Terrence L. Szink and John W. Welch, “King Benjamin’s Speech in the Context of Ancient Israelite Festivals,” in King Benjamin’s Speech: “That Ye May Learn Wisdom”, ed. John W. Welch and Stephen D. Ricks (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 222 n.162 reasoned: “The inclusive mode of sometimes counting the last year as the first of the next jubilee cycle accounts for the frequent confusion between 49- and 50-year jubilee counts.”

- 6. There may be evidence for something similar happening at Qumran in the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Calendric Signs (Otot) scrolls (4Q319) documents a 294-year cycle of 6 jubilees (of 49 years each), correlated to a separate, priestly cycle of 6 years. See Geza Vermes, trans., The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English, revised edition (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2004), 365. According to Roger T. Beckwith, Calendar and Chronology, Jewish and Christian (Boston, MA: Brill, 2001), 92, “in some manuscripts it was extended to seven jubilees.” 4Q319 does mention “[The signs of the] seventh [Jubilee].” (Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 369.)

- 7. Though few may have known of the significance, the jubilee may have still been widely celebrated as a cultural tradition, much like Christmas today is often celebrated not only by Christians commemorating the birth of Christ, but also others who typically see it as a time of for family and gift giving.

- 8. Knauth, “Jubilee, Year of,” 743.

- 9. For themes of the jubilee year, see John W. Welch and J. Gregory Welch, “Benjamin’s Themes Related to Sabbatical and Jubilee Years,” in Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), chart 91.

- 10. Joseph Fielding McConkie, Robert L. Millet, and Brent L. Top, Doctrinal Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 4 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1987–1992), 4:222.

Continue reading at the original source →