The Know

As Alma led his people in a covenant renewal ceremony, perhaps in association with the autumn New Year’s festival season, he asked them 50 penetrating questions to aid in their introspection and spiritual self-evaluations (Alma 5).1 In a pair of particularly pointed questions, Alma asked his people, “Have ye received [God’s] image in your countenances?” (Alma 5:14, emphasis added). Then, inviting them to imagine the judgment day (vv. 15–18), Alma asked if, on that day they could “look up, having the image of God engraven upon you countenances?” (v. 19, emphasis added).

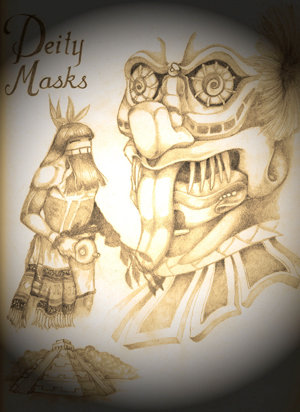

According to Brant Gardner, “Having the image of God engraven on the countenances of the righteous appears to be unique to Alma.”2 By using the terms engraven and image together as he did, Alma might have been making a deliberate allusion to rituals and practices found in pre-Columbian America. As explained by Brant Gardner and Mark Wright, many Mesoamerican cultures participated in rituals of deity impersonation, where “a ritual specialist, typically the ruler, puts on an engraved mask or elaborate headdress and transforms himself into the god whose mask or headdress is being worn.”3

According to Cecelia Klein, participation in the Mesoamerican rituals was limited to the upper class. “The right to impersonate a deity … was not available to everyone; the costumes were signs of rank, office, privilege, and the right to riches.”4 Such rituals were often part of the celebration of fixed calendar dates, such as the New Year,5 with those of lower social status watching the ritual performance.

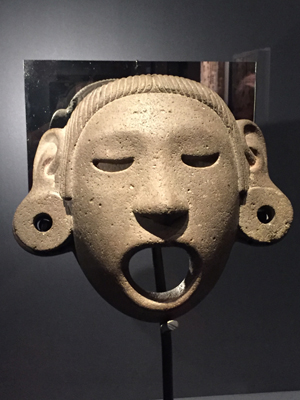

The masks worn by deity impersonators were themselves believed to be “intelligent objects in their own right, embodying the cognitive essence and powers of the [divine] being they represent.”6 As Gardner and Wright explained, “The masks and headdresses that deity impersonators wore were literally graven.”7 Pre-columbian masks were carved or engraved out of turquoise, jade, greenstone, gold, silver, obsidian, wood, and even human skulls.8 In the available artwork, masks “usually appear worn by rulers, priests, and leading warriors.”9

Both deity impersonation and the masks worn for that purpose were linked to the image of deity in pre-Columbian times. According to Klein, the Aztec term referring to a god impersonator literally means “god’s image,”10 and Gardner and Wright noted that Maya inscriptions refer to deity impersonators having u-b’aah-il, “his [the deity’s] holy image.”11 In addition, “the Maya word for mask, koh, means ‘image’ or ‘representative.’”12 Similar rituals and concepts involving masks existed among many pre-Columbian cultures throughout both North and South America.13

Deity mask of Xipe Totec (c 1400-1521, Mexico) from the British Museum. Image via Wikimedia commons.

In Mesoamerica, these masks and rituals are well documented back into Book of Mormon times. Gardner and Wright explained, “This practice goes back to the Formative period (1500 BC–AD 200), as cave paintings in Oxtotitlan dating to the eighth century BC attest.”14 Klein affirmed that carved masks, “appeared in Mesoamerica beginning in the Early Pre-Classic period, after about 1500 BCE.”15 She further declared, “Mesoamericans have been impersonating their gods since … the Middle to Late Formative periods,” or in other words, from about 1000 BC on.16

The Why

“Against that context,” Gardner and Wright concluded, Alma’s questions about receiving and then engraving God’s image upon one’s countenance “become highly nuanced.”17 At this point in time, the church in Zarahemla was dealing with a recent influx of new converts (Alma 4:4–5) who probably brought with them some cultural baggage from their previous religious beliefs and practices. Furthermore, the church was dealing with internal apostasy likely influenced by the Nephites’ surrounding culture (Alma 4:6–14).

As Gardner and Wright proposed, “Alma may have been referencing a concept that he expected his listeners to understand and attempted to shift that understanding into a more appropriate gospel context.”18 Alma was speaking at a covenant renewal ceremony where some in his audience might have expected him to put on an engraved mask and assume the “image” of a god. Instead, Alma taught his people what it truly means to engrave God’s image on one’s countenance.

To Alma, receiving God’s image was akin to being “spiritually … born of God” and having a “mighty change of heart” (Alma 5:14). Andrew C. Skinner explained, “to receive Christ’s image in one’s countenance means to acquire the Savior’s likeness in behavior, to be a copy or reflection of the Master’s life,” which “requires … a change in feelings, attitudes, desires, and spiritual commitment.”19

Receiving God’s image ultimately leads to having God’s image engraved upon one’s countenance. This use of engraven adds rhetorical force to the importance of gaining God’s image, especially in light of the efforts by Book of Mormon authors, who “engraved that which is pleasing unto God” onto metal plates (2 Nephi 5:32).20

Alma compared having God’s image engraved upon oneself to having “a pure heart and clean hands” (Alma 5:19)—a phrase that comes from a temple entry psalm (Psalm 24:4). This psalm was meant to assess a person’s worthiness to pass through the gates of the temple and thereby enter into the presence of God.21 Thus, Alma taught that the righteous who enter into God’s presence will have God’s image engraved upon their countenance. In other words, they “shall be like him” (1 John 3:2; Moroni 7:48).

Achieving this takes more than just dressing up in a costume and performing an “impersonation” ritual. As a pair of LDS scholars put it, receiving the image of God involves genuinely “imitating and emulating … others who have set an example in righteousness, especially Jesus Christ.”22 Ultimately, engraving God’s image onto one’s own countenance is made possible “through the blood of Christ” (Alma 5:27)—because the Lord has “graven thee upon the palms of [His] hands” (Isaiah 49:16; 1 Nephi 21:16).

As Alma taught, this true reception of God’s image was an opportunity available to all—not just the ruler and other social elite. In that way, Alma was continuing the democratizing process begun by King Benjamin and carried further by Mosiah.23 Today, Alma’s penetrating questions continue to urge readers to face up to genuine and probing self-examination. Such introspection opens up the opportunity to repent and become like Christ—to have his image engraven upon one’s countenance—an opportunity open to all who truly seek to emulate the Savior.

Further Reading

Brant A. Gardner and Mark Alan Wright, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 1 (2012): 25–55.

C. Max Caldwell, “‘A Mighty Change of Heart’,” in Alma, The Testimony of the Word, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr., The Book of Mormon Symposium Series, Volume 6 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 27–42.

Andrew C. Skinner, “Alma’s ‘Pure Testimony’ (Alma 5–8),” in Book of Mormon, Part 1: 1 Nephi to Alma 29, ed. Kent P. Jackson, Studies in Scripture, Volume 7 (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1987), 294–306.

- 1. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Alma Ask Church Members Fifty Probing Questions? (Alma 5:14–15),” KnoWhy 112 (June 1, 2016). For a listing of all 50 questions, see John W. Welch and J. Gregory Welch, Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), charts 61–65. For a discussion of Alma 5 in light of ancient Israelite autumn festivals, see Hugh W. Nibley, Teachings of the Book of Mormon: Transcripts of Lectures Presented to an Honors Book of Mormon Class at Brigham Young University, 1988–1990, 4 vols. (American Fork and Provo, UT: Covenant Communications and FARMS, 2004), 2:210–218.

- 2. Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 4:97. Alma’s engraven image of God should not be confused with the graven images universally condemned in the scriptures. See Exodus 20:4; Leviticus 26:1; Deuteronomy 4:16, 23, 25; 5:8; 7:5, 25; 12:3; Judges 17:3–4; 18:14, 17, 20, 30–31; 2 Kings 17:41; 21:7; 2 Chronicles 34:4, 7; Psalms 78:58; 97:7; Isaiah 10:10; 21:9; 30:22; 40:19–20; 42:17; 44:9–10, 15, 17; 45:20; 48:5; Jeremiah 8:19; 10:14; 51:17, 47, 52; Hosea 11:2; Micah 1:7; 5:13; Nahum 1:14; Habakkuk 2:18; 1 Nephi 20:5; 2 Nephi 20:10; Mosiah 12:36; 13:12; 3 Nephi 21:17.

- 3. Brant A. Gardner and Mark Alan Wright, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 1 (2012): 49. See also David L. Webster, “Maya Religion: Deities,” in Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: An Encyclopedia, ed. Susan Toby Evans and David L. Webster (New York, NY: Routledge, 2001), 449: “Rulers or other individuals could wear god costumes, and the Maya apparently believed that the deity manifested itself in the impersonator.”

- 4. Cecelia F. Klein, “Impersonation of Deities,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures, 3 vols., ed. Davíd Carrasco (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2001), 2:36. Klein also explained, “the majority of these masked persons were rulers or high-ranking officials” (p. 33). Walter R. T. Witschey, “Theater,” in Encyclopedia of the Ancient Maya, 341, similarly explained that “performance art, including god-impersonators, masks of deities and spirits,” was “performed by costumed ruling elites of society, divine rulers repeating for all to see the actions and interests of the gods by ‘becoming’ those gods in a spectacle often loaded with religious significance.”

- 5. Mary Miller and Karl Taube, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya (New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 76–77 discuss deity impersonation at various Aztec festivals tied to specific calendar dates. Walter R. T. Witschey, “Rites and Rituals,” in Encyclopedia of the Ancient Maya, ed. Walter R. T. Witschey (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016), 295 discusses “acts of performing art” where Maya “kings impersonated the god they called upon” as part of rituals which were “repeated at fixed intervals determined by the calendar.”

- 6. Cecelia F. Klein, “Masks,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures, 2:175.

- 7. Gardner and Wright, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” 50.

- 8. Klein, “Masks,” 2:176. For examples of masks found in Mesoamerica, see Mary Ellen Miller, The Art of Mesoamerica: From Olmec to Aztec, 5th edition (New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 2012), 8, 19, 94, 233, 268.

- 9. Klein, “Masks,” 2:175.

- 10. Klein, “Masks,” 2:175. Klein, “Impersonation of Deities,” 2:34 explained that the Spanish used nouns like “image,” “likeness,” “surrogate,” and “substitute” to translate the term.

- 11. Gardner and Wright, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” 49. Klein, “Impersonation of Deities,” 2:35 also explained: “Carved stone portraits of Maya dynasts dressed as a god are identified in accompanying inscriptions as u bah, the ‘likeness, image, person, self’ of the god.” See also Stephen Houston and David Stuart, “The Ancient Maya Self: Personhood and Portraiture in the Classic Period,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 33 (1998): 81, 93–94; Stephen Houston, David Stuart, and Karl Taube, The Memory of Bones: Body, Being, and Experience among the Classic Maya (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2006), 66–67, 270.

- 12. Klein, “Masks,” 2:175. Alfredo Barrera Vásquez, et al, Diccionario Maya Cordemex, maya-espanol, espanol-maya (Merida, Mex.: Ediciones Cordemex, 1980), 409, s.v., koh: “el que representa la figura, imagen o persona de otro” (that which represents the form, image or person of another).

- 13. For the Eastern North American (especially Iroquois) cultures, see Raymond D. Fogelson, “Person, Self, and Identity: Some Anthropological Retrospects, Circumspects, and Prospects,” in Psychoscial Theories of the Self, ed. Benjamin Lee (New York, NY: Plenum Press, 1982), 75–77; Harold Blau, “Function and the False Faces: A Classification of Onodaga Masked Rituals and Themes,” Journal of American Folklore 79, no. 314 (1966): 564–580. For the American Southwest, see Virginia More Roediger, Ceremonial Costumes of the Pueblo Indians: Their Evolution, Fabrication, and Significance in the Prayer Drama (Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1991), 158–163. For South America, see Christopher B. Donnan, “Moche Masking Traditions,” in The Art and Archaeology of the Moche: An Ancient Andean Society of the Peruvian North Coast, ed. Steve Bourget and Kimberly L. Jones (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2008), 67–72.

- 14. Gardner and Wright, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” 49. On the Oxtotitlan cave painting, see Miller, The Art of Mesoamerica, 46–47.

- 15. Klein, “Masks,” 2:175.

- 16. Klein, “Impersonation of Deities,” 2:34. As evidence of this, Klein also cited the “cave mural at Oxtotitlan” that Gardner and Wright referenced.

- 17. Gardner and Wright, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” 49–50.

- 18. Gardner and Wright, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” 50.

- 19. Andrew C. Skinner, “Alma’s ‘Pure Testimony’ (Alma 5–8),” in Book of Mormon, Part 1: 1 Nephi to Alma 29, Studies in Scripture, Volume 7, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1987), 301.

- 20. The engraving of the plates was in some sense literally an act of engraving God’s images—characters that form the words of God. Book of Mormon authors wrote using a form of Egyptian writing (1 Nephi 1:2; Mormon 9:32). Egyptian hieroglyphs were literally images of Egyptian deities, and even if the script used was one of the more cursive scripts, such as hieratic or demotic, the characters in these scripts were still based on the original images used in the hieroglyphs. Any syncretism of their Old World scripts with New World scripts likely would have added further hieroglyphic elements since nearly all scripts in Mesoamerica (the only place in the New World with pre-Columbian writing systems) are hieroglyphic.

- 21. Craig C. Broyles, “Psalms Concerning the Liturgies of Temple Entry,” in The Book of Psalms: Composition and Reception, ed. Peter W. Flint and Patrick D. Miller Jr. (Boston, MA: Brill, 2005), 252. See also Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does Nephi Quote a Temple Psalm While Commenting on Isaiah? (2 Nephi 25:16),” KnoWhy 51 (March 10, 2016).

- 22. Joseph Fielding McConkie and Robert L. Millet, Doctrinal Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 4 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1987–1992), 3:30.

- 23. John W. Welch, “Democratizing Forces in King Benjamin’s Speech,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 110–126.

Continue reading at the original source →