The Know

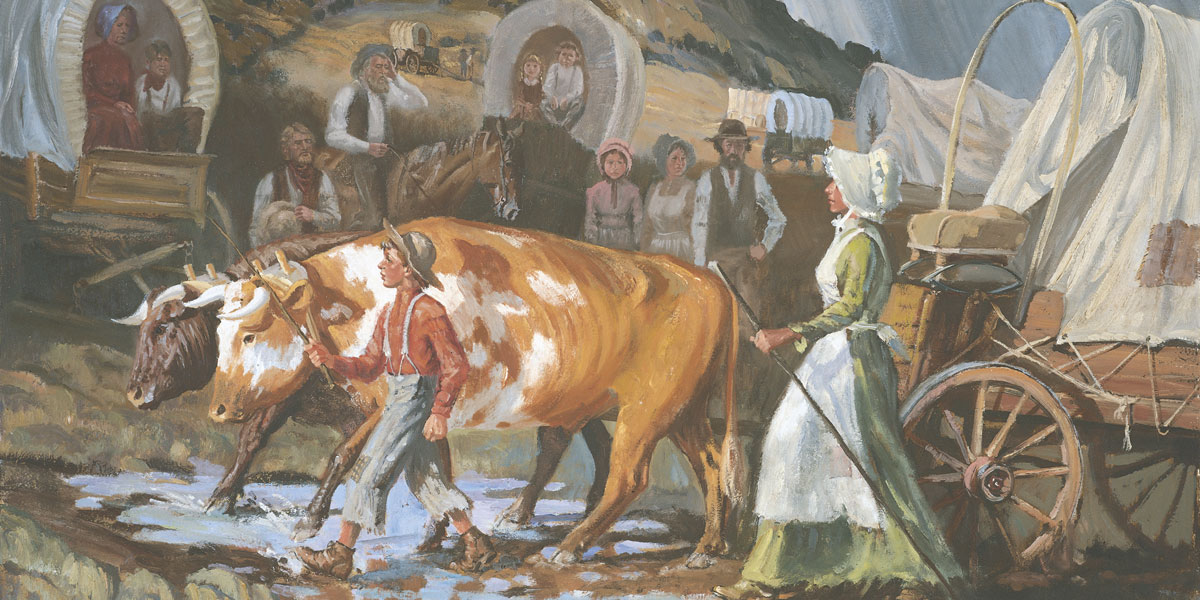

Early in 1846, Brigham Young and 300 others left their beautiful city Nauvoo behind them and crossed the Mississippi river heading west.[1] This was the beginning of an exodus that would take the Mormons all the way across the Great Plains and into the Rocky Mountains. God’s people have often had to relocate to avoid oppression and destruction, and the Saints westward trek is reminiscent of past exoduses, such as the journey that Lehi and his family had taken over 2,000 years earlier.

Both Left their Cities Shortly Before they Were Invaded

Most Mormons left Nauvoo during the first half of 1846. But in September, the small number of Mormons who remained worked together with others who had moved into the area to defend Nauvoo from invaders.[2] In the end, the invasion was successful and the remaining Mormons were forced from the city.[3] In the same way that the saints left Nauvoo shortly before the city was invaded, Lehi and his family left Jerusalem shortly before it was invaded and destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BC.[4]

Both Left Temples Behind, and Built New Ones after Arriving at their Destination

When they left for lands farther west, the Saints had to leave the Nauvoo temple behind, a temple that they had just finished building the year before.[5] This temple was soon burned to the ground. However, on July 28, 1847, after arriving at their new location in the Salt Lake Valley, Brigham Young announced that they would build a new temple there in the Rocky Mountains.[6] They would soon build many temples in their new home. In the same way, Lehi and his family left the temple in Jerusalem behind them when they set off for the New World. This temple was similarly burned to the ground. Also, like the Mormons, Nephi and his people built multiple temples in the New World after their arrival (2 Nephi 5:16).[7]

Both Traveled Along an Established Route and then Changed Direction Part of the Way Through

The Mormons traveled mostly along the famous Oregon Trail until they reached the area near Fort Bridger in present-day Wyoming.[8] They then veered off this trail and traveled south-west into the Salt Lake Valley. In the same way, Lehi and his family spent much of their time traveling along the well-established incense trail heading south from Jerusalem.[9] However, some evidence suggest that at Nahom, they veered off this trail and went “nearly eastward” until they arrived at Bountiful (1 Nephi 17:1).[10]

Both Established a Base Camp Early in the Journey

Initially, Brigham Young had planned on making it all the way from Nauvoo to the Rocky Mountains by the summer of 1846.[11] However, unusual rainfall made the roads so muddy that he had to establish a winter quarters in Nebraska, just across the Iowa border.[12] They stayed here during the winter of 1846–1847, leaving for the Great Basin in the spring.[13] Lehi and his family similarly established a base camp part of the way through the journey: the valley of Lemuel (1 Nephi 2:10). They appear to have stayed at the valley of Lemuel for some time, at least long enough to make two trips back to Jerusalem from this base camp.[14]

Both Had Groups Temporarily Break off to Engage in a Military Action after Leaving

On July 1, 1846, Captain James Allen intercepted the Mormons on their way west at their camp on Mosquito Creek near Council Bluffs, Iowa.[15] He brought a message from President James K. Polk asking that the Mormons provide 500 volunteers to fight in the Mexican-American war.[16] These volunteers broke off from the rest of the group and became the Mormon Battalion. Lehi’s sons also left the rest of the group for a time when they returned to Jerusalem to get the plates.[17] While there, Nephi killed Laban, who was a military commander in Jerusalem.[18] Thus, although this was never their intention, the group was involved in a military action when they were back in Jerusalem.[19]

Both Traveled from a Wetter Urban Area Through a Drier More Sparsely Populated Area

When the Mormons left Nauvoo, they were leaving a wet, green area, surrounded by towns and cities, to travel through the much drier plains and mountain deserts that were much more sparsely populated.[20] In the same way, Lehi and his family left the greenery of Jerusalem and the surrounding areas, which had a comparatively large population, for the mostly uninhabited incense trail (1 Nephi 16:35).[21]

Both Ate “Raw Meat” Along the Trail

During their trek, the Saints would hunt buffalo and other wild game to supplement their food supply. They would eat some of the meat right away, but they would cut the rest of the meat into strips and dry it in the sun to make jerky.[22] They ate this often along the trail. In the same way, the raw meat (1 Nephi 17:2) that Lehi’s family ate in the wilderness was also likely dried into jerky.[23]

Both Were Promised by God that He Would Help Them if they Kept His Commandments

The Lord told the Saints that if they were faithful, “my arm is stretched out in the last days, to save my people Israel” (Doctrine and Covenants 136:22). This is similar to God’s promise in the Book of Mormon,

Inasmuch as ye shall keep my commandments, ye shall prosper, and shall be led to a land of promise; . . . I will prepare the way before you, if it so be that ye shall keep my commandments; wherefore, inasmuch as ye shall keep my commandments ye shall be led towards the promised land; and ye shall know that it is by me that ye are led. Yea, . . . and that I, the Lord, did deliver you” (1 Nephi 2:20; 17:13–14).[24]

The Why

The similarities between the Mormons’ journey to the Great Basin and Lehi’s journey to Bountiful remind the reader of how often the Saints found themselves living out events that were similar to those experienced by the ancient Saints in the Bible and Book of Mormon.[25] In addition, the similarities should remind us that God will deliver us today, just as He delivered the saints in the past. However, these parallels do something else as well: they provide insight into how the Book of Mormon was written.

As Terrence L. Szink stated, “This journey compares with the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt and the Saints' trek to the intermountain region in difficulty, importance, and miraculous nature.”[26] So if someone wanted to write a history of the Mormon journey across the plains that was modeled after Lehi’s journey through Arabia, this would not be difficult to do. He or she would simply have to emphasize the similarities between the events. This would not make either account untrue, it would simply mean that the author was emphasizing certain events in the crossing of the plains to remind the reader of Lehi’s crossing of the desert. As one can see, all the details mentioned in this comparison are historically accurate. They have simply been emphasized to show the similarities between the events.[27]

There are many occasions when the authors of the Book of Mormon did something like this—not the least of which being the way Nephi’s account of their journey parallels the biblical Exodus.[28] They would describe an event in such a way that it would remind the reader of a similar event from the Old Testament or another part of the Book of Mormon. This method of storytelling helps readers notice important connections between the two stories.[29]

This does not mean that either account is somehow incorrect or historically invalid; it simply means that the author wanted the reader to connect the two narratives so they would get deeper meaning from the narrative.[30] Reading the Book of Mormon in this way allows the reader to understand the book better from a literary perspective while still being able to appreciate it as sacred history.

Further Reading

Chad M. Orton, “‘This Shall Be Our Covenant’,” in Revelations in Context: The Stories Behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants, ed. Matthew McBride and James Goldberg (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016), 307–314.

Matthew Bowen, “‘And There Wrestled a Man with Him’ (Genesis 32:24): Enos’s Adaptations of the Onomastic Wordplay of Genesis,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 10 (2014): 151–159.

Noel B. Reynolds, “Lehi as Moses,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 9, no. 2 (2000): 26–35.

S. Kent Brown, “The Exodus Pattern in the Book of Mormon,” in From Jerusalem to Zarahemla: Literary and Historical Studies of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1998), 75–98.

[1] Chad M. Orton, “‘This Shall Be Our Covenant’,” in Revelations in Context: The Stories Behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants, ed. Matthew McBride and James Goldberg (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016), 307.

[2] Richard Bennett, “Barbarously Expelled: The Infamous Nauvoo War of September 1846,” in The Mormon Wars, ed. Glenn Rawson and Dennis Lyman (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2014), 85.

[3] Bennett, “Barbarously Expelled,” 85.

[4] Mordechai Cogan, “Into Exile: From the Assyrian Conquest of Israel to the Fall of Babylon,” in The Oxford History of the Biblical World, ed. Michael D. Coogan (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1998), 266.

[5] Janiece Johnson and Jennifer Reeder, The Witness of Women: Firsthand Experiences and Testimonies from the Restoration (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2016), 122.

[6] Marion D. Hanks, “Salt Lake Temple” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4 vols., ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1992), 3:1253.

[7] For further insights concerning Nephite temples, see Mark Alan Wright, “Axes Mundi: Ritual Complexes in Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 12 (2014): 79–96; John W. Welch, “The Temple in the Book of Mormon: The Temples at the Cities of Nephi, Zarahemla, and Bountiful,” in Temples of the Ancient World, ed. Donald W. Parry (Salt Lake and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1994), 297–387.

[8] Fred R. Gowans and Andrea G. Radke, “Oregon Trail,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowen (Salt Lake City, UT: Desert Book, 2000), 876.

[9] For more on this, see Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 1:81. See also S. Kent Brown, “New Light From Arabia on Lehi’s Trail,” in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson, and John W. Welch (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 2002), 64–69.

[10] See Book of Mormon Central, “Who Called Ishmael’s Burial Place Nahom? (1 Nephi 16:34),” KnoWhy 19 (January 26, 2016).

[11] Orton, “‘This Shall Be Our Covenant’,” 307.

[12] Orton, “‘This Shall Be Our Covenant’,” 307.

[13] Orton, “‘This Shall Be Our Covenant’,” 307.

[14] See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Nephi Believe the Lord Would Prepare a Way? (1 Nephi 3:7),” KnoWhy 263 (January 18, 2017).

[15] Larry C. Porter, Clark V. Johnson, and Susan Easton Black, “Mormon Battalion,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 783–785.

[16] Brian Kelly and Petrea Kelly, Latter-day History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2004), 284–286.

[17] For more on this, see Ben McGuire, “Nephi and Goliath: A Case Study of Literary Allusion in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 18, no. 1 (2009): 16–31.

[18] Book of Mormon Central, “Was Nephi’s Slaying Of Laban Legal? (1 Nephi 4:18),” KnoWhy 256 (January 2, 2017).

[19] Val Larsen, “Killing Laban: The Birth of Sovereignty in the Nephite Constitutional Order,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 16, no. 1 (2007): 26–41, 84–85.

[20] However, Lehi’s group traveled much farther than the Saints did. See H. Donl Peterson, “Father Lehi,” in First Nephi, The Doctrinal Foundation, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr., Book of Mormon Symposium Series, Volume 2 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1988), 63.

[21] George Potter and Richard Wellington, Lehi in the Wilderness: 81 New, Documented Evidences That the Book of Mormon is a True History (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 2003), 22, 41.

[22] Ann Jewell Rowley, “Autobiography,” in Some Early Pioneers of Huntington, Utah and Surrounding Area, ed. James Albert Jones (Emery County, UT: D.H. Mansfield, 1980), 244–246.

[23] Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert/The World of the Jaredites/There Were Jaredites, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley: Volume 5 (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 62, talks about ethnographic reports of people eating strips of raw meat, presumably jerky. In the modern Middle East, people still preserve meat in a way similar to jerky and call it “raw meat.” See Lynn M. Hilton and Hope A. Hilton, Discovering Lehi: New Evidence of Lehi and Nephi in Arabia (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 1996), 139–140; Jeffrey R. Chadwick, “An Archeologist’s View,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 15, no.2 (2006): 74.

[24] Orton, “‘This Shall Be Our Covenant’,” 313.

[25] See, for example, Book of Mormon Central, “Why Is the Sabbath Day Needed? (Mosiah 18:25),” KnoWhy 303 (April 21, 2017).

[26] Terrence L. Szink, “To a Land of Promise (1 Nephi 16–18),” in Book of Mormon, Part 1: 1 Nephi to Alma 29, Studies in Scripture, Volume 7, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1987), 60.

[27] For an example of this in the Book of Mormon, see, Book of Mormon Central, “How Did Enos Liken the Scriptures to His Own Life? (Enos 1:27),” KnoWhy 265 (January 23, 2017).

[28] See, for example, Noel B. Reynolds, “Lehi as Moses,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 9, no. 2 (2000): 26–35.

[29] For an example of this, see Matthew Bowen, “‘And There Wrestled a Man with Him’ (Genesis 32:24): Enos’s Adaptations of the Onomastic Wordplay of Genesis,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 10 (2014): 151–159.

[30] This can be done with the Abinadi narrative and the Moses narrative. See S. Kent Brown, “Moses,” in Book of Mormon Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2003), 568.

Continue reading at the original source →