The Know

For many people, family is the most important thing in life. The same can likely be said for the peoples of the Book of Mormon. Despite their sometimes complex origins, they organized themselves into several core family relationships, just like many other societies in the ancient world.1

It is nearly certain that the Jaredites, Lehites, and Mulekites all encountered other people when they arrived in the New World, and that some of these “others” joined with the new immigrants.2 And it appears that most of those who joined took upon them the tribal names of their new societies.3 This practice, where people not closely related to each other claim to have a family connection, is known as “fictive kinship” and was common in the ancient world.4

One of the best examples of fictive kinship practiced on a large scale comes from ancient Israel. The Israelites were divided into twelve tribes. Each of these tribes was named after one of the sons of Jacob or Joseph, the great patriarchs of the Old Testament.5 However, there were more people in ancient Israel than just those who descended from these early ancestors.6

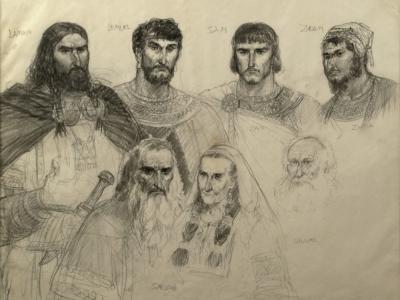

Illustration of the children of Israel offering sacrifices to the Lord. Image by Philip Medhurst via Wikimedia Commons

When the Israelites left Egypt, many non-Israelites went with them, which led to their group being described as a “mixed multitude” (Exodus 12:38).7 And when the Israelites arrived in their Promised Land, many of the people who were already living there, called Canaanites, also seem to have joined them.8 Yet no matter their origins, these newcomers seem to have been adopted into one of Israel’s twelve tribes, even though they were not technically part of these extended family groups.9

Fictive kinship in the Old Testament may help to shed light on fictive kinship in the Book of Mormon, which was also common in pre-Columbian America.10 For example, Lamanites who converted to Christianity called themselves Anti-Nephi-Lehies, (Alma 23:17) directly associating themselves with the ancestor of the Nephites, and by extension, with the Nephites as well. Hundreds of years after the coming of Christ, there were “people who had revolted from the church and taken upon them the name of Lamanites” (4 Nephi 1:20). Events like these show the lasting importance of the Book of Mormon’s original family-based tribes. 11

There are more indirect examples of this as well. Just as there were twelve Israelite tribes that made up Israel, there appear to have been seven Lehite tribes.12 And just as non-Israelites appear to have been assimilated into the tribes of Israel, non-Lehites appear to have been assimilated into the Nephite and Lamanite tribes. One can see this fictive kinship in the first few books of the Book of Mormon. Nephi, for example, built a temple like the temple of Solomon, a feat which would likely have required far more people than the comparatively small portion of Nephi’s immediate family that were loyal to him (2 Nephi 5:16).13

Later on, Jacob stated that “there came a man among the people of Nephi, whose name was Sherem” (Jacob 7:1). Sherem “was learned, that he had a perfect knowledge of the language of the people” (Jacob 7:4). As John Tvedtnes has noted, if Sherem were a Nephite, it would not make sense for him to “come among the people of Nephi,” since he already would have been living among them.

Additionally, one wonders why the text would specifically note that he had a “perfect knowledge of the language of the people” if he were a Nephite. One would expect a Nephite to have a working knowledge of his own language.14 These examples strongly suggest that “others” integrated with the Nephites and Lamanites and identified themselves according to these family names.

The Why

The strong tendency of Book of Mormon peoples to organize according to family units, whether they were originally part of these families or not, shows how fundamental family relationships were to their society. Even when the government failed in 3 Nephi, the family structure did not (3 Nephi 7:2). This is a reminder of the importance family can play for us today.15

However, the Book of Mormon also shows that adopting righteous family relationships sometimes requires sacrifice. It is very likely that some of the people that decided to identify themselves as part of the family of the Nephites left blood relatives behind when they did so. Neil L. Andersen explained the difficulties faced by people in this situation today:

My plea today is for the hundreds of thousands of children, youth, and young adults who do not come from these, for lack of a better term, “picture-perfect” families. I speak not only of the youth who have experienced the death, divorce, or diminishing faith of their parents but also of the tens of thousands of young men and young women from all around the world who embrace the gospel without a mother or father to come into the Church with them. These young Latter-day Saints enter the Church with great faith.16

Ultimately, as Elder Anderson went on to note,

We will continue to teach the Lord’s pattern for families, but now with millions of members and the diversity we have in the children of the Church, we need to be even more thoughtful and sensitive. Our Church culture and vernacular are at times quite unique. The Primary children are not going to stop singing “Families Can Be Together Forever,” but when they sing, “I’m so glad when daddy comes home” or “with father and mother leading the way,” not all children will be singing about their own family.17

Strengthening the family is absolutely essential in today’s world.18 Those whose family situations are not currently ideal can have confidence that, through sacred covenants, they can enter into righteous family relationships. As King Benjamin promised, “And now, because of the covenant which ye have made ye shall be called the children of Christ, his sons, and his daughters” (Mosiah 5:7). Just as the people in the Book of Mormon identified themselves with the family of Nephi, we can all identify ourselves as the children of Christ through our covenants with Him.19

Further Reading

John L. Sorenson, “When Lehi’s Party Arrived in the Land, Did They Find Others There?” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 1, no. 1 (1992): 1–34.

Matthew Roper, “Nephi’s Neighbors: Book of Mormon Peoples and Pre-Columbian Populations,” FARMS Review 15, no. 2 (2003): 89–128; reprinted in The Book of Mormon and DNA Research: Essays from The FARMS Review and the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, ed. Daniel C. Peterson (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 185–218.

The Book of Mormon: It Begins with a Family (Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1993).

- 1. See Arthur R. Bassett, “It Begins with a Family,” in The Book of Mormon: It Begins with a Family (Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1993), 7–19.

- 2. See Book of Mormon Central, “Did Interactions with ‘Others’ Influence Nephi’s Selection of Isaiah? (2 Nephi 24:1),” KnoWhy 45 (March 2, 2016). See also John L. Sorenson, “When Lehi’s Party Arrived in the Land, Did They Find Others There?” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 1, no. 1 (1992): 1–34; John Gee and Matthew Roper, “‘I Did Liken All Scriptures Unto Us’: Early Nephite Understandings of Isaiah and Implications for ‘Others’ in the Land,” in The Fulness of the Gospel: Foundational Teachings from the Book of Mormon, ed. Camille Fronk, Brain M. Hauglid, Patty A. Smith, Thomas A. Wayment (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2003), 51–65; Brant A. Gardner, “The Other Stuff: Reading the Book of Mormon for Cultural Information,” FARMS Review of Books 13, no. 2 (2001): 21–52; Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 154–158.

- 3. For a thorough exploration of this, see Matthew Roper, “Nephi’s Neighbors: Book of Mormon Peoples and Pre-Columbian Populations,” FARMS Review 15, no. 2 (2003): 89–128; reprinted in The Book of Mormon and DNA Research: Essays from The FARMS Review and the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, ed. Daniel C. Peterson (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 185–218.

- 4. Tracy Maria Lemos, “Kinship, Community, and Society,” in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Ancient Israel, ed. Susan Niditch (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2016), 380.

- 5. Even though Jacob only had twelve sons, there are actually thirteen tribes. This is because Joseph’s two sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, were given an inheritance with Jacob’s sons, as noted in Genesis 48:5.

- 6. Kenton L. Sparks, Ethnicity and Identity in Ancient Israel: Prolegomena to the Study of Ethnic Sentiments and Their Expression in the Hebrew Bible (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1998), 328–329.

- 7. For more on this, see Shaul Bar, “Who Were the ‘Mixed Multitude’?” Hebrew Studies 49, (2008): 27–39.

- 8. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did the “Pride Cycle” Destroy the Nephite Nation? (3 Nephi 6:10),” KnoWhy 195 (September 26, 2016).

- 9. Joseph A. Callaway and Hershel Shanks, “The Settlement in Canaan: The Period of the Judges” in Ancient Israel: From Abraham to the Roman Destruction of the Temple, 3rd edition, ed. Hershel Shanks (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 2011), 59–83. See also Hershel Shanks, William G. Dever, Baruch Halpern, and P. Kyle McCarter Jr., The Rise of Ancient Israel (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1992).

- 10. Patricia A. McAnany, Living with the Ancestors: Kinship and Kingship in Ancient Maya Society, 2nd edition (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013), xxviii.

- 11. See Book of Mormon Central, “Where Did Joseph Smith Get His Teachings on the Family? (3 Nephi 18:21),” KnoWhy 285 (March 10, 2017).

- 12. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Lehi Divide His People into Seven Tribes? (Jacob 1:13),” KnoWhy 319 (May 29, 2017).

- 13. See Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 1:351–356; 2:6–13, 102–103.

- 14. John A. Tvedtnes, “New Approaches to the Book of Mormon: Explorations in Critical Methodology,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 6, no. 1 (1994): 28–29.

- 15. For a general treatment of the importance of the family in society, see Reed H. Bradford, “Family: Teachings About the Family,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4 vols., ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1992), 2:486–488.

- 16. Neil L. Andersen, “‘Whoso Receiveth Them, Receiveth Me,’” Ensign, May 2016, 49–50, online at lds.org.

- 17. Andersen, “‘Whoso Receiveth Them, Receiveth Me,’” 50, online at lds.org.

- 18. For more information on how the Book of Mormon teaches us to do this, see Kenneth W. Anderson, “What Parents Should Teach Their Children from the Book of Mosiah” in Mosiah, Salvation Only Through Christ, The Book of Mormon Symposium Series, Volume 5, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate, Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1991), 23–36.

- 19. See Book of Mormon Central, “How Can the Book of Mormon Strengthen Marriages and Families? (Jacob 3:7),” KnoWhy 302 (April 19, 2017).

Continue reading at the original source →