Editor’s Note: This is the first part of the second contribution to my new series Nephite History in Context: Artifacts, Inscriptions, and Texts Relevant to the Book of Mormon. Check out the really cool (and official, citable) PDF version here. To learn more about this series, read the introduction here. To find other posts in the series, see here.

Apocryphon of Jeremiah (4Q385a)

Background

|

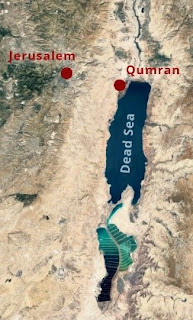

| The Dead Sea Scrolls were found in 11 different caves near Qumran between 1947-1956. Map by Jasmin Gimenez. |

Between 1947 and 1956, a few well preserved scrolls and tens of thousands of broken fragments were found scattered across eleven different caves along the northwest shores of the Dead Sea near Qumran. Now known as the Dead Sea Scrolls, they are arguably the most significant discovery ever made for the study of the Bible and the origins of Judaism and Christianity. Among the writings found are the earliest copies of nearly every Old Testament book, many of the known apocryphal and pseudepigraphic works, and several other texts discovered for the first time at Qumran. Altogether, more than 900 different compositions were found, most of which are written in Hebrew, though some are in Aramaic and Greek. Various dating methods indicate that they were written over time between the late third century BC and the mid-first century AD.1

One of the fragmentary, non-biblical texts found is a story about the prophet Jeremiah commonly called the “Apocryphon of Jeremiah,” although it has sometimes been called “A Jeremiah Apocryphon,” and “Pseudo-Jeremiah.” According to Geza Vermes, the text is “written in well-imitated biblical Hebrew,” and appears to date to around the first century BC.2 The exact composition of the story is uncertain, and debate remains about which fragments belong to this text and which belong to a different story about Ezekiel, Jeremiah’s contemporary.3 In general, though, the story seems to focus around Jeremiah prophesying that a remnant of exiled Israel will return to their homeland only to be destroyed 490 years (ten jubilees) later for once again turning away from the Lord.4

Translation

The following excerpt is from 4Q385a frg. 18a–b col. i.5 The translation is from Kipp Davis, The Cave 4 Apocryphon of Jeremiah and the Qumran Jeremianic Traditions: Prophetic Persona and the Construction of Community Identity (Boston, MA: Brill, 2014), 132 (a transcription of the Hebrew can be seen on the same page),6with annotations added:

Jeremiah the prophet from yhwh’s presence.7 [And the ]captives who were led captive [went up] from the land of Jerusalem,8and they came [to Riblah,9 to ]the king of Babylon[, ]when Nebuzaradan, the overseer of the bodyguard had slaughtered [the people of G]od.10And he took the furnishings from the house of God with the priests,11[ … ]12 the sons of Israel, and brought them to Babylon. And Jeremiah the prophet walked [with them as far as ]the river,13 and he instructed them concerning what they ought to do in the land of[ their ]captivity.14 [And they listened] to the voice of Jeremiah,15to the words that God had instructed to him [for them to do.16 So ]they kept the covenant of the God of their fathers in the land of [their captivity. They turned ]from what they, their kings, priests, [and their princes ]had done[ ] … [ … ]profane[d the na]me of God, to [sin].17

Book of Mormon Relevance

|

| Cave 4 (pictured) held the majority of the scrolls, including 4Q385a and others containing the Apocryphon of Jeremiah. Photo: Effie Scweizer, Wikipedia.org |

This passage is generally believed to be part of either the introduction or the conclusion of the extant text.18 In it, Jeremiah travels to a river with the captives “from the land of Jerusalem” (ירושלים מארץ) in the wake of the Babylonian invasion ca. 587–586 bc, counseling them along the way on how they should live while in captivity. The designation of the captives’ homeland as the “land of Jerusalem,” which may actually occur twice in this Jeremiah apocryphon (cf. 4Q389 frg. i),19 is distinct from biblical references to Jerusalem and Judah. The phrase is not used anywhere in biblical texts, although fourteenth century BC tablets written in Akkadian use variations of an equivalent phrase (see NHC 2b), indicating the great antiquity of this term for the region around Jerusalem.

Here in the Apocryphon of Jeremiah, Kipp Davis believes the phrase “land of Jerusalem” fits the overall “portrayal of ‘the land’ throughout the text,” which “is restricted only to the holy city.”20 While the text likely dates to the first century BC, this more restricted portrayal of the region as “the land of Jerusalem,” according to Robert Eisenman and Michael Wise, “greatly enhances the sense of historicity of the whole, since Judah … by this time consisted of little more than Jerusalem and its immediate environs.”21

The setting of 1 Nephi is very similar to that of the Apocryphon of Jeremiah. Not only are the events in 1 Nephi contemporary to Jeremiah’s ministry (1 Nephi 7:14), but the story is about Jerusalem natives who departed from the land in the wake of a Babylonian invasion about a decade earlier (ca. 598–597 bc), in which the temple was ransacked and captives were taken (see 1 Nephi 1–2; cf. 2 Kings 24:9–17; 2 Chronicles 36:9–10; Jeremiah 37:1), and Judah was likely reduced to essentially a city-state centered in Jerusalem, the once “great city” (cf. 1 Nephi 1:4; 2:13; 10:3; 11:13).22 Then, like the captives in the Jeremiah apocryphon, Nephi and his family travel through the wilderness until reaching a river where they were given further instructions and commandments through a prophet (Lehi), and received covenant promises from the Lord (see 1 Nephi 2–7). However, Nephi learned through prophetic means that in several hundred years his people would ultimately be destroyed for turning away from the Lord (1 Nephi 12:13–19).

Significantly, the phrase “land of Jerusalem” also shows up several times in 1 and 2 Nephi (see table). Furthermore, travel in and out of the city is always between “(the land of) Jerusalem” and the “wilderness,” with no mention of other settled territory in between (see 1 Nephi 2:2–4, 11; 3:2–4, 9–10, 17–18, 23–27; 4:1–4, 24–30, 38; 5:6; 7:1–7), indicating a similarly restricted portrayal of “the land” as little more than a city-state centered on the holy city itself. Given the similarities between the settings in both texts, we can reasonably say this “greatly enhances the sense of historicity” of Nephi’s narrative as well.23

Uses of “Land of Jerusalem” in 1 and 2 Nephi* | |

1 Nephi, headnote | “The Lord warns Lehi to depart out of the land of Jerusalem … Nephi taketh his brethren and returns to the land of Jerusalem” |

1 Nephi 2:11 | “he had led them out of the land of Jerusalem” |

1 Nephi 3:9–10 | “go up to the land of Jerusalem … we had gone up to the land of Jerusalem” |

1 Nephi 5:6 | “journeyed in the wilderness up to the land of Jerusalem” |

1 Nephi 7:2, 7 | “again return into the land of Jerusalem … desirous to return unto the land of Jerusalem” |

1 Nephi 16:35 | “brought them out of the land of Jerusalem” |

1 Nephi 17:14, 20, 22 | “did bring you out of the land of Jerusalem … hath led us out of the land of Jerusalem … were in the land of Jerusalem” |

1 Nephi 18:24 | “brought from the land of Jerusalem” |

2 Nephi 1:1, 3, 9, 30 | “bringing them out of the land of Jerusalem … flee out of the land of Jerusalem … shall bring out of the land of Jerusalem … brought out of the land of Jerusalem” |

2 Nephi 25:11 | “return again and possess the land of Jerusalem” |

*The phrase continued to be used by later writers in reference to their ancestral homeland. See Jacob 2:25, 31–32; Omni 1:6; Mosiah 1:11; 2:4; 7:20; 10:12; Alma 3:11; 9:22; 10:3; 22:9; 36:29; Helaman 5:6; 7:7; 8:21; 16:19; 3 Nephi 5:20; 16:1; 20:29; Mormon 3:18–19; Ether 13:7. Alma 24:1 uses in the phrase in reference to a new land called Jerusalem by later Lamanites. | |

Notes

1. For background on the Dead Sea Scrolls, see James VanderKam and Peter Flint, The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Their Significance for Understanding the Bible, Judaism, Jesus, and Christianity (San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 2002). See also Eugene Ulrich, “Dead Seas Scrolls,” in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, ed. David Noel Freedman (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000), 326–329; Joseph A. Fitzmyer, “The Dead Sea Scrolls,” in HarperCollims Bible Dictionary, rev. and updated, ed. Mark Allan Powell (New York, NY: HarperOne, 2011), 183–188.

2. Geza Vermes, trans., The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English, rev. ed. (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2004), 602.

3. See VanderKam and Flint, Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls, 231.

4. See Michael Wise, Martin Abegg Jr., and Edward Cook, trans., The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation (New York, NY: HarperOne, 2005), 439–446. Out of all the translations I’ve consulted, this one’s arrangement of the fragments produces the most readable narrative.

5. In the early publications of this fragment, which predated the “official” publication in the Discoveries in the Judaean Desert series, it was referred to as “fragment 1” of “Pseudo-Jeremiah” from scroll 4Q385 (or 4Q385b). See Robert Eisenman and Michael Wise, trans., The Dead Sea Scrolls Uncovered: The First Complete Translation and Interpretation of 50 Key Documents withheld for over 35 Years (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1992), 57–58; Florentino García Martínez, trans. The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, 2nd ed. (New York, NY and Grand Rapids, MI: Brill and Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1996), 285. Later it was classified as 4Q385b frg. 16 col. i, as seen in Florentino García Martínez and Eibert J. C. Tigchelaar, trans., The Dead Sea Scrolls: Study Edition, 2 vols. (New York, NY: Brill, 1999), 2:772–773. It’s now referred to as 4Q385a frg. 18 col. i or 4Q385a frg. 18a–b col. i, as seen in Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 602; Wise, et al., New Translation, 446; Donald W. Parry and Emanuel Tov, The Dead Sea Scrolls Reader, 6 vols., 2nd ed. (Boston, MA: Brill, 2013), 2:802–803; and Davis, Cave 4 Apocryphon of Jeremiah, 132.

6. All brackets and ellipses are in the original. I have omitted representation of the blank first line, and the lacuna at the beginning of the text.

7. The sense here may be that Jeremiah was leaving the Lord’s presence, as indicated in several translations. Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 602: “Jeremiah the Prophet [departed] from before the Lord (YHWH)”; Wise, et al., New Translation, “[… And] Jeremiah the prophet, [went out] from before the Lord”; Devorah Dimant, trans., in Parry and Tov, Reader, 2:803: “[and] Jeremiah the Prophet [went out] from before the Lord”; Martínez and Tigchelaar, Study Edition, 2:773: “[… and] Jeremiah the Prophet [went] from before yhwh.” More consistent with Davis is Eisenman and Wise, Uncovered, 58: “Jeremiah the Prophet before the Lord” and Martínez, Qumran Texts, 285: “Jeremiah the prophet before yhwh.”

8. Several translators restore the lacuna at the beginning of this line as indicating that Jeremiah came and joined the captives. Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 602: “… [to accompany the] captives who were taken captive from the land of Jerusalem”; Wise, et al., New Translation, 446: “[and went with the] captives who were taken captive from the land of Jerusalem”; Dimant, in Parry and Tov, Reader, 2:803: “[and he went with the] captives who were led captive from the land of Jerusalem.” More consistent with Davis are Martínez and Tigchelaar, Study Edition, 2:773: “[… the] exiles who were brought into exile from the land of Jerusalem”; Eisenman and Wise, Uncovered, 58: “[… wh]o were taken captive from the land of Jerusalem”; Martínez, Qumran Texts, 285: “[…w]ho were made prisoners of Jerusalem.”

9. Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 602 restores “[to … Nebuchnezzar]” (who was the king of Babylon at the time) here instead of “[to Riblah, to,]” while Eisenman and Wise, Uncovered, 58; Martínez, Qumran Texts, 285; Martínez and Tigchelaar, Study Edition, 2:773 just leave this space blank. Wise, et al., New Translation, 446 and Dimant, in Parry and Tov, Reader, 2:803 are both consistent with Davis.

10. This differs from all other translations I’ve consulted, which typically leave this lacuna blank and opt for a less extreme term in the place of “slaughtered.” Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 602 and Dimant, in Parry and Tov, Reader, 2:803 have “smote”; Wise, et al., New Translation, 446 and Martínez and Tigchelaar, Study Edition, 2:773 each have “struck.” Eisenman and Wise, Uncovered, 58 and Martínez, Qumran Texts, 285 each stop after “guard” or “escort.”

11. Most translations use “vessels” rather than “furnishings,” suggesting that this refers to the sacred relics of the temple. See Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 602; Martínez and Tigchelaar, Study Edition, 2:773; Dimant, in Parry and Tov, Reader, 2:803; Eisenman and Wise, Uncovered, 58; Martínez, Qumran Texts, 285. Wise, et al., New Translation, 446 has “utensils.”

12. Dimant, in Parry and Tov, Reader, 2:803 and Wise, et al., New Translation, 446 restore “the nobles” here. Consistent with Davis, Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 602; Martínez and Tigchelaar, Study Edition, 2:773; Eisenman and Wise, Uncovered, 58; Martínez, Qumran Texts, 285 all leave this lacuna blank.

13. Martínez and Tigchelaar, Study Edition, 2:773 and Eisenman and Wise, Uncovered, 58 leave the lacuna before “the river” blank, while Martínez, Qumran Texts, 285 is even missing “the river.” Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 602; Wise, et al., New Translation, 446; and Dimant, in Parry and Tov, Reader, 2:803 are all consistent with Davis.

14. Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 602; Martínez and Tigchelaar, Study Edition, 2:773; Dimant, in Parry and Tov, Reader, 2:803; Eisenman and Wise, Uncovered, 58; Wise, et al., New Translation, 446 all indicate that Jeremiah “commanded” rather than merely “instructed” the captives. This is true in both instances of “instructed” in this passage. Martínez, Qumran Texts, 285 curiously has “laughed and told” here, and has “decreed” in the second instance of “instructed.”

15. There is some variation in how the lacuna in this section is dealt with and translated. Vermes agrees with Davis that this indicates something the captives did, while Wise, et al. and Dimant both make it another of Jeremiah’s commands. Martínez and Tigchelaar; Eisenman and Wise; Martínez all leave it blank. Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 602: “[And they obeyed] the voice of Jeremiah”; Wise, et al., New Translation, 446: “[that they should listen] to the voice of Jeremiah”; Dimant, in Parry and Tov, Reader, 2:803: “[(that) they should listen] to the voice of Jeremiah”; Martínez and Tigchelaar, Study Edition, 2:773: “[…] by the voice of Jeremiah”; Eisenman and Wise, Uncovered, 58: “ … to the voice of Jeremiah”; Martínez, Qumran Texts, 285: “[…] by the voice of Jeremiah.”

16. Wise, et al., New Translation, 446 and Dimant, in Parry and Tov, Reader, 2:803 simply have “commanded him [to do],” making Jeremiah, and not the people, the subject of the instructions or commands from God. Martínez and Tigchelaar, Study Edition, 2:773; Eisenman and Wise, Uncovered, 58; Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 602; Martínez, Qumran Texts, 285 all leave the lacuna blank, which also effectively makes Jeremiah the subject of the command.

17. Owing to the fragmentary nature of these final lines, there are several differences in other translations that impact, at least somewhat, the meaning of the passage. Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 602: “And they were to keep the covenant of the God of their fathers in the land [of their captivity … and they were not to d]o as they had done and their kings and priests [and … and they] profaned [the na]me of God”; Wise, et al., New Translation, 446: “that they should keep the covenant that the God of their fathers in the land [of Babylon, that they should not do] as they had done, they themselves, their kings, their priests, [and their princes … for they had] profaned [the nam]e of God”; Dimant, in Parry and Tov, Reader, 2:803: “and they should keep the covenant of the God of their fathers in the land [of Babylon and they shall not do] as they had done, they themselves and their kings and their priests [and their princes ] [(namely, that) they ]defiled[ the na]me of God to[ desecrate]”; Martínez and Tigchelaar, Study Edition, 2:773: “they will keep the covenant of the God of their fathers in the land of [their exile …] as they and their kings, their priests did […] … […] God […]”; Martínez, Qumran Texts, 285: “they will keep the covenant of the God of their fathers in the country of [exile …] what they and their kinds and their priests did […] God […].”

18. Vermes, Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, 602 positions it at the beginning; Wise, et al., New Translation, 446 position it toward the end.

19. See Davis, Cave 4 Apocryphon of Jeremiah, 142–143: “in the land of J[erusalem]” ([י[רושלים בארץ). Wise, et al., New Translation, 441 and Dimant, in Parry and Tov, Reader, 2:814–815 restore it as “in the land of J[udah]” or “in the land of J[udaea]” ([הודה]י בארץ), but as Davis points out, “Judah” is never used in the extent text to refer to the land. Thus, he reasons that in light of 4Q385a frg. 18a–b col. i and the overall portrayal of the Jewish homeland in the text, “land of Jerusalem” makes better sense here.

20. Davis, Cave 4 Apocryphon of Jeremiah, 143.

21. Eisenman and Wise, Uncovered, 58.

22. See Neal Rappleye, “Jerusalem Chronicle (ABC 5/BM 21946),” Nephite History in Context 1 (November 2017): 1–5. Interestingly, this source refers to Jerusalem as “the city of Judah,” perhaps indicating that Judah had been reduced to little more than the city itself. See also Daniel C. Peterson, Matthew Roper, and William J. Hamblin, “On Alma 7:10 and the Birthplace of Jesus Christ,” (FARMS Transcripts, 1995).

23. See Gordon C. Thomasson, “Revisiting the Land of Jerusalem,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 139–141; cf. Peterson et al., “On Alma 7:10.”

Continue reading at the original source →