Editor’s Note: In a previous KnoWhy, a brief introduction to stylometry and a review of stylometric studies on the Book of Mormon was presented.1 Building on that foundation, this KnoWhy discusses recent stylometric research exploring the ability of novelists to create distinct authorship styles or “voices” for multiple fictional characters

The Know

To date, the combined data from several valid stylometric studies on the Book of Mormon have demonstrated that it has multiple, distinct writing styles and that those styles are consistent with the authors designated within the text itself.2 One may naturally wonder, though, if the Book of Mormon’s diversity of style is in any way unique or impressive. Is it possible that a creative writer could have produced its variety of distinct styles?

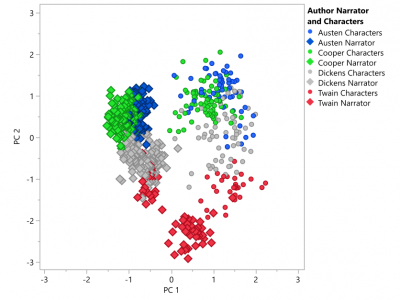

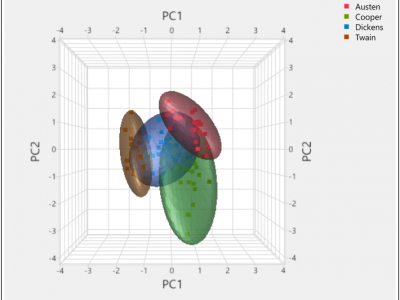

Several early studies using simplistic stylometric methods suggested that it is indeed possible for a talented author to create multiple styles or “voices” for different fictional characters.3 In a recent study, using a more robust method, Matt Roper, Paul Fields, and Larry Bassist found persuasive evidence to confirm this hypothesis.4 Using a statistical technique called principal component analysis (PCA), they analyzed the function-word patterns of fictional characters created by four highly regarded 19th century novelists: Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), and James Fenimore Cooper.5

Their results show that, to varying degrees, each author was able to create a distinct voice for multiple fictional characters, including the narrators, in their stories. As the following graph demonstrates, the narrators form clusters on the left, while the fictional characters form somewhat looser clusters on the right. Each dot represents a 2,000-word chunk of the character’s text.

Because in all cases the narrators had distinctly different function word frequencies than non-narrators, the research team re-fitted the PCA to only assess the diversity of voices among non-narrators. On these non-narrator voices, they performed four separate multivariate tests,6 all of which resulted in statistically significant differences among character voices.7

The combined data from these tests show that the differences in function-word patterns among the non-narrator characters of these four authors are significant. Statistically speaking, it can be said that Mark Twain’s character, Tom Sawyer, really does have a different “voice” than his friend Huckleberry Finn, and that the voice of Jane Austen’s Elizabeth Bennet is truly distinct from her love interest, Mr. Darcy. While these characters’ voices still generally cluster together by the author who created them, they are distinct enough to consider them as statistically separate from one another.8

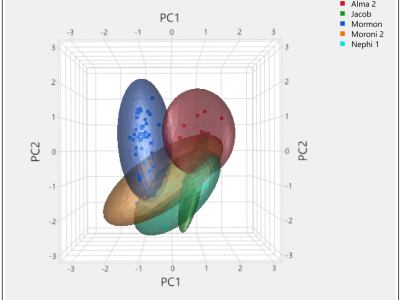

Having successfully detected distinct voices for fictional characters created by 19th century novelists, the research team next applied this same stylometric method to the writings of characters in the Book of Mormon. The following graph shows the diversity of voices in the Book of Mormon, with ellipsoid clouds demonstrating how the writings of major Book of Mormon authors form distinct clusters. In total, the Book of Mormon contains 28 distinct voices that are detectable using stylometric analysis.

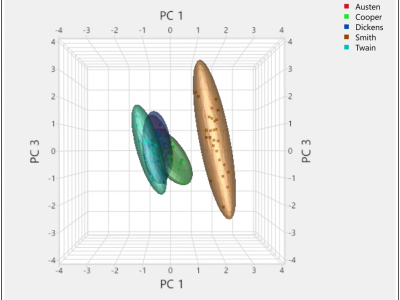

Amazingly, after measures were taken to standardize the two studies for valid comparisons,9 the results showed that the level of voice diversity among Book of Mormon characters surpassed the diversity among fictional characters created by the 19th century novelists. The Book of Mormon’s voice diversity value was more than twice that of the average for the 19th century novelists. In addition, the research team’s findings show that the Book of Mormon’s character diversity is larger than even the composite diversity achieved by four of the most widely-recognized, talented nineteenth-century novelists as contained in eight of their works combined!10

The Why

These statistical results provide striking support for the Book of Mormon’s internal claims about its authorship.11 Even if Joseph Smith had been a skilled and experienced writer, in order to fabricate the Book of Mormon, he would have needed an ability to create distinct fictional voices that was beyond some of the greatest novelists of his day. Yet Joseph himself, and those who knew him best, all insisted that he was relatively uneducated.12

Furthermore, literary scholar Robert A. Rees has argued that in contrast to the great works produced by Joseph Smith’s Romantic Era contemporaries, there is no evidence that he engaged in any preparatory literary efforts before translating the Book of Mormon.13 Rees explained,

There is … no evidence that [Joseph] was keeping a journal or developing his writing style, no record of his writing sketches or short stories, no indication that he was creating the major characters of the Nephite history, planning its plots, or working out the major themes and ideas found in its pages; nor is there any evidence that he was consciously developing an authorial voice or cultivating a personal writing style (or that he even understood what this would have entailed). Neither did he exhibit any proclivity for composing large narrative forms or differential styles or anything at all like the complex, interwoven, episodic components of the Book of Mormon.14

This situation makes the results of the stylometric analysis all the more astounding. It is difficult to imagine that a frontier farmer, with limited formal education and no literary accomplishments whatsoever, could have created a work of fiction with such a diverse array of statistically distinct voices.

Moreover, previous stylometric studies have demonstrated that none of the 19th century writers usually suspected of authoring the Book of Mormon have writing samples that match any of its distinct styles. These writers include Sidney Rigdon, Solomon Spalding, W. W. Phelps, Oliver Cowdery, Parley P. Pratt, and Joseph Smith himself.15

Thus, in order for one of these candidates to be the true author of the Book of Mormon, he would have needed to write in such a way as to completely mask his own style while at the same time creating a diversity of voices that was beyond some of the most talented novelists of their day! This combination of achievements seems highly unlikely for any of them, and especially for Joseph Smith, who was the least educated and experienced of them all.16

In contrast to this scenario, the Book of Mormon’s own claims about its authorship can easily accommodate the results of this recent stylometric analysis. If the Book of Mormon’s source texts were truly written by a large number of ancient prophets over the course of 1,000 years, then that would naturally explain why its voice diversity is greater than the composite diversity achieved by four of the most distinguished novelists of the 19th century. In light of these recent findings, it can be said that stylometry’s statistical methods have once again helped us discern “the evidence of things not [otherwise] seen” (Hebrews 11:1).17

Further Reading

Book of Mormon Central, “What Can Stylometry Tell Us about Book of Mormon Authorship? (Jacob 4:4),” KnoWhy 389 (December 12, 2017).

Matthew Roper, Paul J. Fields, and G. Bruce Schaalje, “Stylometric Analyses of the Book of Mormon: A Short History,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 21, no. 1 (2012): 28–45.

John L. Hilton, “On Verifying Wordprint Studies: Book of Mormon Authorship,” BYU Studies Quarterly, 30, no. 3 (1990): 89–108; reprinted in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited: The Evidence for Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 225–253.

- 1. See Book of Mormon Central, “What Can Stylometry Tell Us about Book of Mormon Authorship? (Jacob 4:4),” KnoWhy 389 (December 12, 2017).

- 2. See Book of Mormon Central, “What Can Stylometry Tell Us about Book of Mormon Authorship? (Jacob 4:4),” KnoWhy 389 (December 12, 2017); Matthew Roper, Paul J. Fields, and G. Bruce Schaalje, “Stylometric Analyses of the Book of Mormon: A Short History,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 21, no. 1 (2012): 28–45.

- 3. See John Frederick Burrows, Computation into Criticism: A Study of Jane Austen's Novels and an Experiment in Method (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1987); Tim Hiatt and John Hilton, “Can Authors Alter Their Wordprints? Faulkner's Narrators in As I Lay Dying,” in Deseret Language and Linguistic Society Symposium 16 no. 1 (1990); Tim Hiatt, “Can Authors Alter Their Wordprints? James Joyce’s Ulysses,” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1990).

- 4. This team personally communicated the results of their ongoing and intriguing research to Book of Mormon Central staff, and it is being reported with their full permission.

- 5. Among other reasons, these authors were chosen because they are each known for their unique and distinctive characters, because they were contemporaries with Joseph Smith, and because they represent both English and American literature.

- 6. These tests included Pillai’s Trace, Wilks’ Lambda, Hotelling’s T-squared, and Roy’s Largest Root.

- 7. For all tests, the chance that the differences occurred simply by chance alone was less than 1 in 1000 (p < .001).

- 8. For instance, Tom Sawyer’s voice is different from Huckleberry Finn’s voice, but their voices are more like the voices of other characters created by Twain than they are like the voices of characters created by Austen.

- 9. The study standardized each author’s volume by dividing by that author’s number of characters and taking the kth root, where k = the number of principal components used in the analysis.

- 10. The composite diversity for the 19th century authors was calculated by encompassing the speakers from all eight of the novels by the four nineteenth century authors with one giant ellipsoid, as if they were the creation of one author. The encompassing ellipsoid for the Book of Mormon speakers is larger in volume than the giant encompassing ellipsoid for the four nineteenth century authors.

- 11. This statement doesn’t suggest that the stylometric analysis demonstrates that the characters in the Book of Mormon were truly ancient prophets and that they actually wrote the portions of the Book of Mormon that are ascribed to them. Rather it means that the expanse of voice diversity in the Book of Mormon is consistent with its claims of having been written by numerous prophets over a 1,000-year span, while at the same time being inconsistent with the theories that Joseph Smith or any other proposed 19th century author was responsible for creating its content.

- 12. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Would God Use an Uneducated Man to Translate the Book of Mormon? (2 Nephi 27:19),” KnoWhy 397 (January 9, 2017).

- 13. See Robert A. Rees, “Joseph Smith, the Book of Mormon, and the American Renaissance,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 35, no. 3 (2002): 83–112; Robert A. Rees, “Joseph Smith, the Book of Mormon, and the American Renaissance: An Update,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 19 (2016): 1–16. For a comparison of Joseph Smith’s translation of the Book of Mormon with John Milton’s dictation of Paradise Lost, see Robert A. Rees, “John Milton, Joseph Smith, and the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies Quarterly 54, no. 3 (2015): 6–18.

- 14. Rees, “John Milton, Joseph Smith, and the Book of Mormon,” 12.

- 15. See Wayne A. Larsen, Alvin C. Rencher, and Tim Layton, “Who Wrote the Book of Mormon? An Analysis of Wordprints,” in Book of Mormon Authorship: New Light on Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1982), 163; John L. Hilton, “On Verifying Wordprint Studies: Book of Mormon Authorship,” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited: The Evidence for Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 253, n. 22; Paul J. Fields, G. Bruce Schaalje, and Matthew Roper, “Examining a Misapplication of Nearest Shrunken Centroid Classification to Investigate Book of Mormon Authorship,” Mormon Studies Review 23, no. 1 (2011): 107.

- 16. For Joseph Smith’s limited education, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Would God Use an Uneducated Man to Translate the Book of Mormon? (2 Nephi 27:19),” KnoWhy 397 (January 9, 2017). It’s possible that multiple 19th century authors could have collaborated on such a project, but that only makes the historical argument more difficult to sustain. There is simply no valid historical evidence that any of these individuals, let alone a group of them, conspired to fabricate the Book of Mormon. Furthermore, it is difficult to imagine that not just one, but two or more writers would be able to successfully mask their personal writing styles in a way that would be undetectable by the stylometric analysis. Besides, even with a few more collaborative writers in the mix, this scenario would still require them to jointly produce a book with greater character diversity than the composite diversity achieved by four of the best novelists of their day, and from eight of their novels combined.

- 17. For the appropriateness of searching out and using such evidences to support and supplement faith, see Jeffrey R. Holland, “The Greatness of the Evidence,” Chiasmus Jubilee, August 16, 2017, online at bookofmormoncentral.org.

Continue reading at the original source →