The Know

During Lehi’s travel through ancient Arabia, his sons needed to slay animals for food from time to time in order for their group to avoid starvation. Nephi reported on one occasion that he went hunting and broke his bow, “which was made of fine steel” (1 Nephi 16:18). And because his brothers’ bows had “lost their springs, it began to be exceedingly difficult, yea, insomuch that [they] could obtain no food” (v. 21).

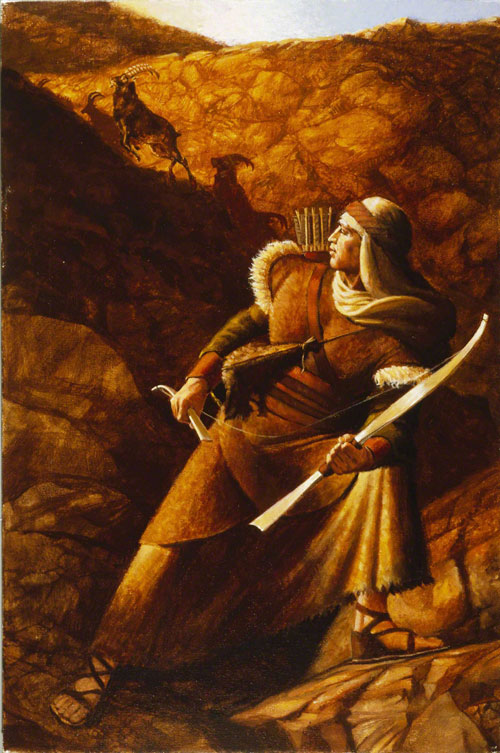

In response to their dire situation, Laman, Lemuel, the sons of Ishmael, and even Lehi all began to “murmur against the Lord” (1 Nephi 16:20). In contrast, Nephi encouraged them by saying “many things unto them in the energy of [his] soul” (v. 24). He then “made out of wood a bow, and out of a straight stick, an arrow” and went to his father for guidance (v. 23). Lehi humbled himself and consulted the Liahona. It directed Nephi to the top of a mountain, where he “did slay wild beasts, insomuch that [he] did obtain food for [their] families” (1 Nephi 16:31).

Although this story may seem rather unremarkable, it may actually be loaded with symbolic importance. In the ancient Near East, kingly status, military power, and the right to rule were all symbolized by the bow.1 Thus “to break the bow” was a common idiom which meant to bring an enemy or ruler into submission.2 In Nephi’s circumstances, most of the adult males in the group, except for Nephi, murmured and complained against the Lord. It took the breaking of the bow, as well as chastisement from Nephi and from the Lord Himself, before they finally “humbled themselves” (1 Nephi 16:24).

This story, like Nephi’s slaying of Laban, also helps confirm the Lord’s promise that Nephi would be a teacher and ruler over his brothers (2 Nephi 5:19).3 According to Noel B. Reynolds, “What we tend to read as a story of flight from Jerusalem is really a carefully designed account explaining to [Nephi’s] successors why their religious faith in Christ and their political tradition—the kingship of Nephi—were both true and legitimate.”4 Nephi’s newly created bow symbolized that he was Lehi’s rightful prophetic successor. It foreshadowed his future kingship. And it demonstrated that, according to divine appointment, he was taking “the lead of their journey in the wilderness” (Mosiah 10:13).

The Why

The story of the broken bow adds one more layer of authenticity to Nephi’s record. The breaking of the bow, the loss of spring in his brothers’ bows, Nephi’s ability to fashion a new bow from apparently suitable wood, and the need to make a new arrow are all believable details according to what is known about ancient bows, archery, and the geography of southwest Arabia.5 Moreover, it is unlikely that Joseph Smith came up with this story because, as Alan Goff has argued, it gives “precisely the right biblical symbolism to apply to Nephi as he begins to assert his leadership.”6

This story is also a reminder that the Lord calls and prepares leaders of His choice. Laman and Lemuel may have been more qualified in their own eyes to lead, but the Lord’s appointments to leadership positions are according to His divine knowledge and will. As a prophet follows divine direction, it becomes apparent to the people, as it was in the case of Nephi, that the mantle of prophetic leadership is truly upon him.7

When trials come our way, we can follow Nephi’s example. Instead of murmuring or blaming others, we can encourage them, take the initiative to search for solutions, and then seek the Lord’s guidance. Doing so will help us similarly qualify for revelation. Importantly, it was upon the “top of the mountain” that Nephi found the wild game he was looking for. When we seek answers to our own vexing concerns, the Lord may likewise direct us to His holy temples. In these sacred locations, symbolic of mountaintops, the Lord often rewards obedience and sacrifice with a proverbial ram in the thicket—an unexpected means of salvation or deliverance.8

Further Reading

Alan Goff, “A Hermeneutic of Sacred Texts: Historicism, Revisionism, Positivism, and the Bible and Book of Mormon,” (MA dissertation, Brigham Young University, 1970), 92–99.

William J. Hamblin, “Nephi’s Bows and Arrows,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 41–43.

Noel B. Reynolds, “Nephi’s Political Testament,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1991), 220–229.

- 1. Alan Goff, “A Hermeneutic of Sacred Texts: Historicism, Revisionism, Positivism, and the Bible and Book of Mormon,” (MA dissertation, Brigham Young University, 1989), 92–99.

- 2. See Nahum W. Waldman, “The Breaking of the Bow,” The Jewish Quarterly Review 69, no. 2 (1978): 82–33.

- 3. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Was the Sword of Laban So Important to Nephite Leaders? (Words of Mormon 1:13),” KnoWhy 411 (February 27, 2018).

- 4. Noel B. Reynolds, “Nephi’s Political Testament,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1991), 221. See also, Noel B. Reynolds, “The Political Dimension in Nephi’s Small Plates,” BYU Studies Quarterly 27, no. 4 (1987): 15–37.

- 5. See William J. Hamblin, “The Bow and Arrow in the Book of Mormon,” in Warfare in the Book of Mormon, ed. Stephen D. Ricks and William J. Hamblin (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 365–399; William J. Hamblin, “Nephi’s Bows and Arrows,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 41–43; George Potter and Richard Wellington, Lehi in the Wilderness: 81 New Documented Evidence That the Book of Mormon Is a True History (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, Inc., 2003), 99–105.

- 6. Alan Goff, “Dan Vogel’s Family Romance and the Book of Mormon as Smith Family Allegory,” FARMS Review 17, no. 2 (2005): 388.

- 7. See J. R euben Clark, Jr., “When Are the Writings and Sermons of Church Leaders Entitled to the Claim of Scripture?” Address to Seminary and Institute Personnel, BYU, July 1954: “The Church will know by the testimony of the Holy Ghost in the body of the members, whether the Brethren in voicing their views are ‘moved upon by the Holy Ghost’; and in due time that knowledge will be made manifest.” This statement was quoted in D. Todd Christofferson, “The Doctrine of Christ,” Ensign, May 2012, online at lds.org.

- 8. See Genesis 22:13.

Continue reading at the original source →