The Know

In the first chapter of the Book of Mormon, Nephi explained that he was not going to make a “full account” of the things which his father had written (1 Nephi 1:16). He then stated, “after I have abridged the record of my father then will I make an account of mine own life” (1 Nephi 1:17). This declaration of intent may lead readers to wonder where, exactly, Nephi made the transition between summarizing his father’s record and writing his own.

In a groundbreaking study on the structural outline of Nephi’s first book, Noel B. Reynolds proposed that this division takes place between chapters 9 and 10 of 1 Nephi.1 One reason for this is that Nephi’s language at the beginning of chapter 10 seems to indicate that the promised narrative shift would occur here: “And now I, Nephi, proceed to give an account upon these plates of my proceedings, and my reign and ministry” (v. 1).

Another clue comes from the fact that the formal ending of chapter 9 (“And thus it is. Amen”) is repeated again at the conclusion of chapter 22, the last chapter in Nephi’s first book:

|

But the Lord knoweth all things from the beginning; wherefore, he prepareth a way to accomplish all his works among the children of men; for behold, he hath all power unto the fulfilling of all his words. And thus it is. Amen. |

Wherefore, ye need not suppose that I and my father are the only ones that have testified, and also taught them. Wherefore, if ye shall be obedient to the commandments, and endure to the end, ye shall be saved at the last day. And thus it is. Amen. |

Importantly, these are the only two verses in Nephi’s record that contain this phrase. Reynolds proposed that these concluding statements act as bookends to two separate textual units, with chapters 1–9 being the first unit and chapters 10–22 making up the second unit.2

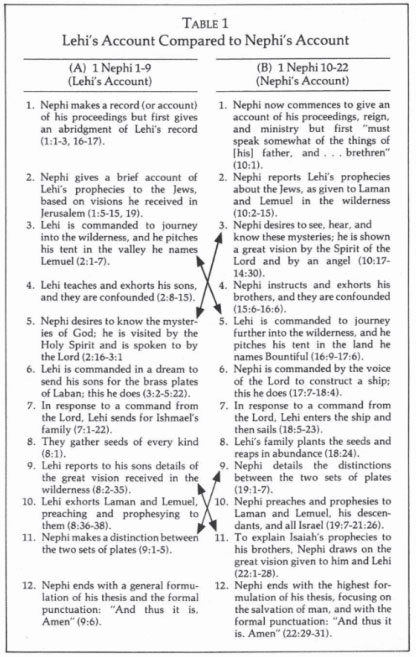

In order to test this theory, Reynolds carefully analyzed the structure of each of these major units. He found that they significantly mirrored one another and that the subunits within the larger structures contained a number of close parallels and meaningful relationships. The following chart can help readers identify the parallel sections in Nephi’s two-part record, including two chiastic (inverted) relationships which Reynolds explained at length in the body of his article.3

Generally speaking, Lehi plays a larger role in the first unit (chapters 1–9). Aside from Nephi’s editorial remarks, Lehi’s unit opens up with an account of Lehi’s prophecies about the destruction of Jerusalem (1 Nephi 1:4–15), and it closes with Lehi’s dream of the Tree of Life (1 Nephi 8). Moreover, in this unit’s deliverance episodes, Lehi was the primary leader of the group. For example, it was Lehi who “did speak unto [Laman and Lemuel] in the valley of Lemuel, with power, being filled with the Spirit, until their frames did shake before him” (1 Nephi 2:14; emphasis added). It was Lehi who received the commandment to get the plates of brass from Laban (1 Nephi 3:2–4). And it was Lehi who encouraged family members, including his wife Sariah, to trust in the Lord and not murmur (1 Nephi 5:4–6).

In contrast, the second unit (chapters 10–22) quickly transitions into Nephi’s expanded vision of the Tree of Life (1 Nephi 11–15), and it ends with Nephi’s prophecies about the restoration of Israel in the last days. In this unit’s deliverance episodes, Nephi began to fulfill his role as Lehi’s prophetic successor.4 Instead of Lehi taking the lead, it was Nephi who spoke unto Laman and Lemuel while being “filled with the power” (1 Nephi 17:48), and who “did shake them, even according to the word which he had spoken” (v. 54; emphasis added). It was Nephi who received the commandment to build a ship (vv. 7–8). And it was Nephi who encouraged Lehi to remain faithful after Lehi himself murmured against the Lord (1 Nephi 16:20–25).

The Why

Because Nephi did not directly explain the structure of his writings, it is impossible to know with certainty where his summary of his father’s record ended and the account of his own proceedings began.5 Yet a break between 1 Nephi 9–10 is especially inviting. It nicely explains (1) the unique formal conclusions to chapters 9 and 22, (2) Nephi’s emphasis on his own “reign and ministry” in 1 Nephi 10:1, (3) why Lehi’s prophecies and leadership role is emphasized in chapters 1–9 and then Nephi’s prophecies and leadership role is emphasized in chapters 10–22, and (4) the many structural parallels between the two proposed units.

Why would Nephi make such a division in the first place? There are several interesting possibilities. In one sense, the related units seem to act as dual witnesses of many important truths, such as the coming of the Messiah and the power of God’s deliverance. In this way, Lehi and Nephi act together in unity as father and son and as prophetic witnesses of Christ.6

On another level, the second unit often expands upon and clarifies the teachings in the first unit. For instance, Nephi’s vision of the Tree of Life explains the symbolism from his father’s dream.7 This, perhaps, is meant to show how personal revelation was needed before Nephi could understand the meaning of his father’s revelations. It also shows how revelation necessarily builds upon revelation, “line upon line and precept upon precept” (2 Nephi 28:30).8

Finally, Nephi’s unit simultaneously shows how he became his father’s rightful prophetic successor and how Laman and Lemuel became increasingly hard hearted. These developments didn’t happen overnight, and Nephi’s two part-structure illustrates the major transitions that led to them. The structural division helps explain why Nephi was chosen as a king over his people, why Laman and Lemuel sought to kill him, and why Lehi’s posterity was ultimately divided into two opposing factions: Nephites and Lamanites.9

With all of this in mind, identifying Nephi’s narrative transition between his and his father’s teachings may be crucial for understanding the purposes of his record. It can also help readers discern valuable principles which they can then apply into their personal lives. These principles and insights include the need for two or more witnesses of the truth, a better understanding of personal spiritual development, a model for obtaining a spiritual witness of sacred truths, a warning about how murmuring and rebellion lead to being cut off from God’s presence, and a greater appreciation for how further revelations often expand upon and clarify the content of prior revelations.

Further Reading

Noel B. Reynolds, “Nephi’s Political Testament,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1991), 220–229.

See Noel B. Reynolds, “The Political Dimension in Nephi’s Small Plates,” BYU Studies Quarterly 27, no. 4 (1987): 15–37.

Noel B. Reynolds, “Nephi’s Outline,” in Book of Mormon Authorship: New Light on Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1982), 53–74.

- 1. See Noel B. Reynolds, “Nephi’s Outline,” in Book of Mormon Authorship: New Light on Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1982), 53–74.

- 2. See Reynolds, “Nephi’s Outline,” 56–57. S. Kent Brown has similarly proposed that 1 Nephi 1–10 make up Nephi’s summary of his father’s record. See S. Kent Brown, “Nephi’s Use of Lehi’s Record,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1991), 6.

- 3. This chart is derived from Reynolds, “Nephi’s Outline,” 58.

- 4. See Noel B. Reynolds, “The Political Dimension in Nephi’s Small Plates,” BYU Studies Quarterly 27, no. 4 (1987): 14.

- 5. For the lack of certainty and finality about this proposed structure, see, Reynolds, “Nephi’s Outline,” 72–73: “There are undoubtedly … aspects of my hypothesis which may raise doubts in the minds of readers. Whether or not the patterns outlined above are exactly right, there is ample evidence that Nephi was consciously working with rhetorical patterns and devices. In this article I have attempted to identify only a few such elements. As others are identified, the patterns suggested here will undoubtedly be revised or even replaced.”

- 6. The concept of mutually sustaining prophetic witnesses also plays an important role in the chiastic structure of 2 Nephi. See Noel B. Reynolds, “Chiastic Structuring of Large Texts: Second Nephi as a Case Study” in To Seek the Law of the Lord: Essays in Honor of John W. Welch, ed. Paul Y. Hoskisson and Daniel C. Peterson (Orem UT: The Interpreter Foundation, 2017), 340–341. See also, Bruce A. Van Orden, “The Law of Witnesses in 2 Nephi,” in Second Nephi, The Doctrinal Structure, Book of Mormon Symposium Series, Volume 3, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1989), 307–321.

- 7. See John W. Welch and J. Gregory Welch, Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), chart 92.

- 8. This principle is also expressed in the ninth Article of Faith: “We believe all that God has revealed, all that He does now reveal, and we believe that He will yet reveal many great and important things pertaining to the Kingdom of God.”

- 9. See Noel B. Reynolds, “Nephi’s Political Testament,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1991), 220–229.

Continue reading at the original source →