The Know

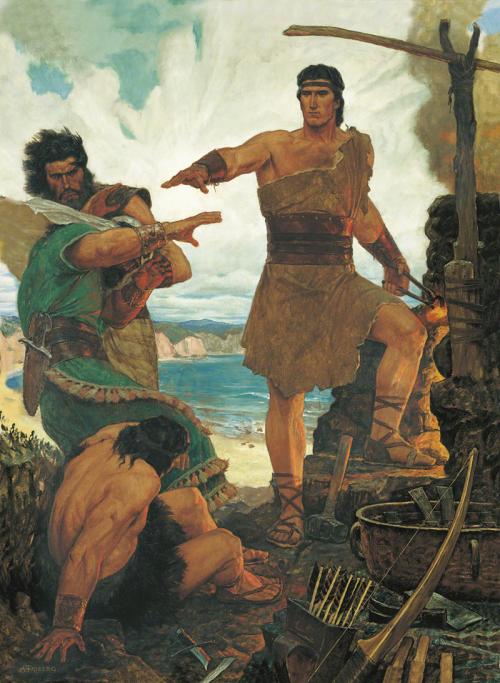

Early on in the book of 1 Nephi, the Lord promised Nephi that if he would keep God’s commandments he would “be made a ruler and a teacher over [his] brethren” (1 Nephi 2:22). As their family’s wilderness journey progressed, this prophecy began to be fulfilled.1 Yet Nephi’s brothers complained that Nephi had taken this position of ruler and teacher upon himself, which led them to be angry with Nephi and rebellious towards God (1 Nephi 16:37–38).

Many years later, after the family had arrived and settled in the promised land, Nephi was asked by his people to become their king. Although he preferred that they have no king, he accepted the position anyway. It seems this was at least partly due to Nephi remembering the Lord’s prophecy about him being a ruler:

And behold, the words of the Lord had been fulfilled unto my brethren, which he spake concerning them, that I should be their ruler and their teacher. Wherefore, I had been their ruler and their teacher, according to the commandments of the Lord, until the time they sought to take away my life. (2 Nephi 5:19)

Although it defied cultural expectations, the elevation of a younger brother over his elder siblings is a recurring theme in the sacred writings of ancient Israel. Some of the great patriarchs and kings of Israel—including Jacob, Joseph, Judah, Ephraim, David, and Solomon—were given similar promises by the Lord and chosen over elder brothers. As in Nephi’s account, the fulfillment of those promises is clearly demonstrated in the scriptures.

Although Jacob and his brother Esau were twins, Esau was born first and therefore should have received the birthright. In the turn of events in which Jacob was able to secure the birthright blessing in place of his older brother, their father Isaac pronounced the following upon Jacob:

“Let people serve thee, and nations bow down to thee: be lord over thy brethren, and let thy mother’s sons bow down to thee” (Genesis 27:29). The kingdom of Edom, populated by Esau’s descendants, would eventually become a vassal state to Israel after they were conquered by King David (2 Samuel 8:14).

David, whose lineage was to sit on the throne of Israel for all time, was of the tribe of Judah.2 Judah had been promised, in a blessing from his father, Jacob, that he would rule over his siblings. Although he was the fourth-born son, his patriarchal blessing declared: “Judah, thou art he whom thy brethren shall praise: thy hand shall be in the neck of thine enemies; thy father’s children shall bow down before thee” (Genesis 49:8). Additionally, he was promised that “the scepter shall not depart from Judah” until the time of the Messiah (Genesis 49:10).

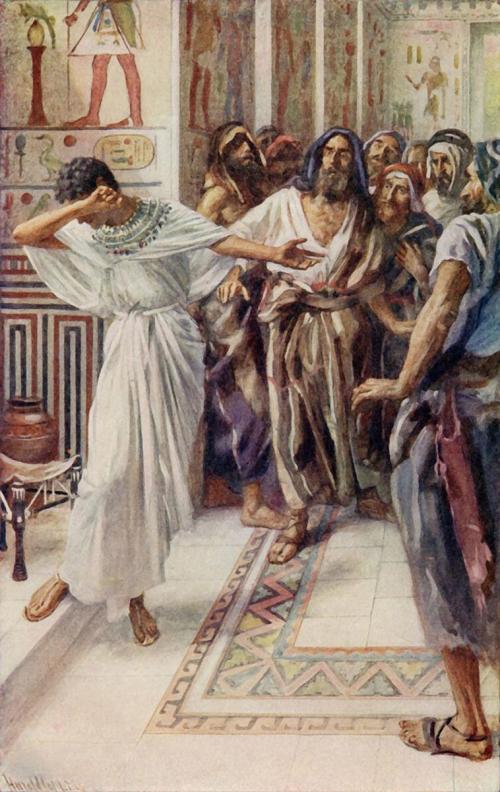

Joseph, another son of Jacob, received a similar blessing from the Lord. One of Jacob’s youngest sons, Joseph was shown in dreams that his family members would eventually bow down before him (Genesis 37:6–10). Just as Nephi’s brothers were angry with him, the biblical record states that Joseph’s brothers “hated him yet the more for his dreams, and for his words” (Genesis 37:7).3

Joseph’s brothers were so upset by his perceived pretentiousness that they sold him as a slave into Egypt. Ironically, this event eventually led to Joseph becoming a governor over that land (a vice-regent to Pharaoh) and to the fulfillment of his prophetic dreams. When his family was in need and came to Egypt for food, “Joseph’s brethren came, and bowed down themselves before him with their faces to the earth,” just as he had foreseen (Genesis 42:6).

This pattern continued with Joseph’s own sons, Manasseh and Ephraim, who, when their grandfather Jacob blessed them, he put his right hand on younger Ephraim’s head for the birthright blessing rather than on the eldest son Manasseh’s (Genesis 49:13–14).

The Why

These connections show that Nephi ruled over his older brothers much like his ancestor Joseph did, as well as a line of early patriarchal figures including Joseph’s son Ephraim, his older brother Judah, his father Jacob, and also figures like Moses and David.4 So, while Nephi’s ascendency over his brothers defied the cultural expectations and patriarchal order of his day, it was still supported by ample scriptural precedent.

Although the birthright was typically passed on to the firstborn son even if the father’s preferences were otherwise (Deuteronomy 21:15–17), the scriptures record many instances in which that blessing and inheritance were granted to a younger son. In general, the reason for this seems to have been that the younger son was simply more righteous. For example, in the case of the first sibling rivalry recorded in the Bible, between Cain and Abel, the Lord favored Abel because of his greater obedience (Moses 5:16–23).

This was the case with Nephi as well. When Lehi saved his family by leading them into the wilderness, his oldest sons, Laman and Lemuel, murmured against him “because they knew not the dealings of that God who had created them” (1 Nephi 2:12). Nephi, although he was the younger son, repeatedly turned to the Lord for answers. As a result, Nephi noted, the Lord “did soften my heart that I did believe all the words which had been spoken by my father; wherefore, I did not rebel against him like unto my brothers” (1 Nephi 2:16).

Whereas Laman and Lemuel were eventually “cut off from the presence of the Lord” for their rebellion, Nephi was “blessed” and given greater responsibility because of his faith (1 Nephi 2:19, 21). The examples of Nephi and others demonstrate that no matter what our situation or position is in life, which is often out of our control, the Lord will judge us based upon our righteousness and bless us accordingly. “For the Lord seeth not as man seeth; for man looketh on the outward appearance, but the Lord looketh on the heart” (1 Samuel 16:7).

Further Reading

Alan Goff, “A Hermeneutic of Sacred Texts: Historicism, Revisionism, Positivism, and the Bible and Book of Mormon,” (MA dissertation, Brigham Young University, 1989), 104–132.

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Was the Sword of Laban So Important to Nephite Leaders? (Words of Mormon 1:13),” KnoWhy 411 (February 27, 2018).

Samuel Tongue, “Sibling Rivalries and Younger Sons,” Bible Odyssey, online.

- 1. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Nephi Include the Story of the Broken Bow? (1 Nephi 16:23),” KnoWhy 421 (April 3, 2018); Book of Mormon Central, “Why Was the Sword of Laban So Important to Nephite Leaders? (Words of Mormon 1:13),” KnoWhy 411 (February 27, 2018).

- 2. David was also a younger son who was elevated over his brethren because the Lord looked “not on his countenance, or on the height of his stature,” his “outward appearance,” but looked “on the heart” (1 Samuel 16:7). His kingdom continued through his son Solomon, also a later-born son.

- 3. For a wordplay on the name Joseph and its relationship to his brother’s anger, see Matthew L. Bowen, “‘Their Anger Did Increase Against Me’: Nephi’s Autobiographical Permutation of a Biblical Wordplay on the Name Joseph,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 23 (2017): 115–136. For more similarities between Nephi and Joseph, see Book of Mormon Central, “How Was Nephi Similar to Joseph of Egypt? (1 Nephi 18:18),” KnoWhy 416 (March 15, 2018).

- 4. See Alan Goff, “A Hermeneutic of Sacred Texts: Historicism, Revisionism, Positivism, and the Bible and Book of Mormon,” (MA dissertation, Brigham Young University, 1989), 104–132; Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), 42–44; Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 1:47; Book of Mormon Central, “How Was Nephi Similar to Joseph of Egypt? (1 Nephi 18:18),” KnoWhy 416 (March 15, 2018).

Continue reading at the original source →