The Know

The prophet Moroni felt self-conscious about the wording of the Book of Mormon. He explained that “when we write we behold our weakness, and stumble because of the placing of our words” (Ether 12:25). For this reason, he was worried that the “Gentiles will mock at these things” (v. 23).

Soon after the Book of Mormon came off the press in 1830, Moroni’s fears were realized. Alexander Campbell, one of the first and most influential critics of the Book of Mormon, claimed that it was “without exaggeration, the meanest book in the English language.” He further declared that, other than its quotations from the Bible, the book had “not one good sentence in it.”1

Although Campbell was overly negative in his assessment of the Book of Mormon’s language, it is understandable that he and others felt its original wording sounded a little strange. That is because it really was strange, even in the 1830s. Joseph Smith himself even seemed to have thought so because, when preparing for the Book of Mormon’s republication in 1837,2 he revised many of its non-standard words and phrases.3

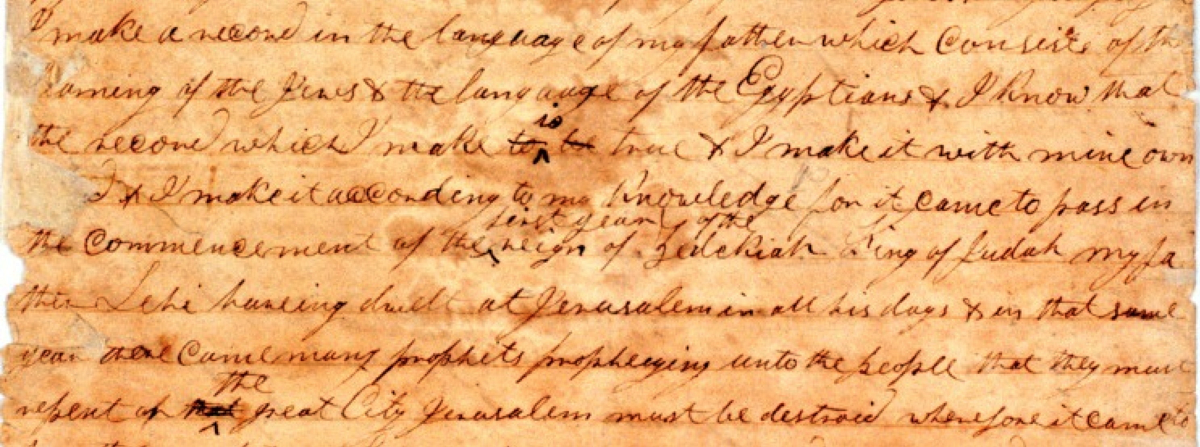

For many years, believers and critics alike have assumed that the Book of Mormon’s unusual grammar was simply a product of Joseph Smith’s rural dialect, or that it might be the result of an uneducated speaker trying to sound biblical. Yet in a surprising turn, recent linguistic research has proven that almost every non-standard word or phrase in the Book of Mormon shows up as acceptable usage in an earlier period of the English language, called Early Modern English.4

For instance, Campbell apparently took issue with the phrase “had spake” in 2 Nephi 4:14: “For I had spake many things unto them.”5 Most English speakers today would feel that “had spake” is a grammatical error and should be replaced with “had spoken.” Yet “had spake” shows up as an appropriate usage in Early Modern English, as seen in a text from 1614: “if he had spake of the power of Anti-Christ.”6

Campbell similarly found the wording in Alma 31:36, which states that Alma “clapped his hands upon all they which were with him,” to be problematic.7 Today’s standard English doesn’t allow for a subjective pronoun like “they” to be used as an object in a sentence. We would expect it to say “upon all them who were with him.” Yet, once again, the Book of Mormon’s usage is well-attested in Early Modern English. A text from 1489, for instance, states that a man “made all they that were with him … to be hanged.”8

Dozens of similar examples could be cited.9 Moreover, many of the Book of Mormon’s words and much of its syntax (the way words are arranged) are from the same Early Modern period. While some of its archaic features can indeed be found in the Bible, others were last used in texts written well before Joseph Smith’s day—sometimes a couple hundred years before.10

The Why

Whatever the source of the Book of Mormon’s archaic language may be, it should be obvious that the idea of “bad” grammar is a relative concept. All languages naturally evolve over time, and therefore the rules about what qualifies as correct and incorrect usage are always changing. While phrases like “had spake” and “upon all they which were with him” may grate against modern readers’ notions of correct grammar, they were perfectly acceptable by earlier English standards.

Thankfully, early members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints weren’t all that concerned with the Book of Mormon’s grammar anyway. What they cared about was the message about Christ that was behind its language, and the spiritual power that accompanied the message.11 Their favorable reception, despite those who might mock the Book of Mormon’s wording, is exactly what the Lord prophesied would take place.12 To Moroni, the Lord declared, “Fools mock, but they shall mourn; and my grace is sufficient for the meek, that they shall take no advantage of your weakness” (Ether 12:26).

The Lord further explained that if people will “humble themselves before me, and have faith in me, then will I make weak things become strong unto them” (Ether 12:27). In a way, this situation is happening with the language of the Book of Mormon. For many years it has been discounted as having defective grammar. Now, with the help of modern databases and search engines, the very things that were seen as “bad” English are turning out to be remarkably and surprisingly “good” English—just from a different time period than expected and not from Joseph Smith.

This situation can help readers see why it is important to ignore those who mock and persecute that which is good and holy. The prophet Isaiah declared, “Woe unto them that call evil good, and good evil; that put darkness for light, and light for darkness; that put bitter for sweet, and sweet for bitter!” (Isaiah 5:20). As we humble our hearts and ask the Lord to help us see spiritual truths, we will be able to discern that which is good,13 even if those who rely exclusively upon a worldly perspective cannot see it.14

Further Reading

Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack, The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon, Part Three: The Nature of the Original Language (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2018).

Stanford Carmack, “Is the Book of Mormon a Pseudo-Archaic Text?” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 28 (2018): 177–232.

and Stanford Carmack, “Editing Out the ‘Bad Grammar’ in the Book of Mormon,” The Interpreter Foundation, 2016

Stanford Carmack, “Exploding the Myth of Unruly Book of Mormon Grammar: A Look at the Excellent Match with Early Modern English,” The Interpreter Foundation/BYU Studies, 2015.

Stanford Carmack, “A Look at Some ‘Nonstandard’ Book of Mormon Grammar,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 11 (2014): 209–262.

- 1. Alexander Campbell, Delusions (Boston, MA: Waitt and Dow’s Press, 1832,) 15.

- 2. For the text of the 1837 edition, see “Book of Mormon, 1837,” The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 24, 2018, online at josephsmithpapers.org.

- 3. For information about various editions of the Book of Mormon, see Royal Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon, Volume 4 of the Critical Text of the Book of Mormon, (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2014); Royal Skousen, “Conjectural Emendation in the Book of Mormon,” FARMS Review 18, no. 1 (2006): 187–231; Royal Skousen, “Book of Mormon Editions (1830–1981),” The Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4 vols., ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1992), 1:175–176; George Horton, “Understanding Textual Changes in the Book of Mormon,” Ensign, December 1983, online at lds.org.

- 4. See Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack, The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon, Part Three: The Nature of the Original Language (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2018), 621.

- 5. See Campbell, Delusions, 14. For the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon, see “Book of Mormon, 1830,” p. 69, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 23, 2018, online at josephsmithpapers.org.

- 6. Skousen and Carmack, The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon, 632.

- 7. Campbell, Delusions, 14. See also, “Book of Mormon, 1830,” p. 313, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 24, 2018, online at josephsmithpapers.org.

- 8. Skousen and Carmack, The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon, 637, 655.

- 9. See Skousen and Carmack, The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon, 621–658.

- 10. For ranging treatments of the Book of Mormon’s archaic lexical, syntactic, and grammatical features, see Skousen and Carmack, The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon; Stanford Carmack, “Is the Book of Mormon a Pseudo-Archaic Text?” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 28 (2018): 177–232; Stanford Carmack, “Barlow on Book of Mormon Language: An Examination of Some Strained Grammar” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 27 (2017): 185–196; Stanford Carmack, “How Joseph Smith’s Grammar Differed from Book of Mormon Grammar: Evidence from the 1832 History” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 25 (2017): 239–259; Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack, “Editing Out the ‘Bad Grammar’ in the Book of Mormon,” The Interpreter Foundation, 2016; Stanford Carmack, “The Case of the {-th} Plural in the Earliest Text,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 18 (2016): 79–108; Stanford Carmack, “The Case of Plural Was in the Earliest Text,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 18 (2016): 109–137; Stanford Carmack, “Joseph Smith Read the Words,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 18 (2016): 41–61; Stanford Carmack, “The More Part of the Book of Mormon is Early Modern English,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 18 (2016): 33–40; Stanford Carmack, “Exploding the Myth of Unruly Book of Mormon Grammar: A Look at the Excellent Match with Early Modern English,” The Interpreter Foundation/BYU Studies, 2015; Royal Skousen, “‘A theory! A theory! We have already got a theory, and there cannot be any more theories!’” The Interpreter Foundation/BYU Studies, 2015; Stanford Carmack, “Why the Oxford English Dictionary (and not Webster’s 1828),” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 15 (2015): 65–77; Stanford Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 14 (2015): 119–186; Stanford Carmack, “What Command Syntax Tells Us About Book of Mormon Authorship,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 13 (2015): 175–217; Stanford Carmack, “A Look at Some ‘Nonstandard’ Book of Mormon Grammar,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 11 (2014): 209–262.

- 11. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Is the Book of Mormon So Focused on Jesus Christ? (2 Nephi 25:26),” KnoWhy 484 (November 13, 2018).

- 12. See Book of Mormon Central, “What Role Does the Book of Mormon Play in Missionary Work? (2 Nephi 30:3),” KnoWhy 288 (March 17, 2017).

- 13. See Moroni 10:6: “And whatsoever thing is good is just and true; wherefore, nothing that is good denieth the Christ, but acknowledgeth that he is.”

- 14. See Quentin L. Cook, “When Evil Appears Good and Good Appears Evil,” Ensign, March 2018, online at lds.org; from a devotional address, “A Banquet of Consequences: The Cumulative Result of All Choices,” given at Brigham Young University, February 7, 2017, online at speeches.byu.edu.

Continue reading at the original source →