I'm not sure what happened, but I think something was lost in the translation of Book of Abraham knowledge to the information shared to a group of students and, via the Internet, to many others. As I pondered this issue, it suddenly hit me: if portions of our own scriptures can be temporarily unavailable (like the sealed portion of the gold plates, and, well, the plates themselves) or lost (like the 116 pages of the Book of Mormon) or burned (like a major part of Joseph Smith's collection of scrolls, apparently burned in the Great Chicago Fire), then of course there can be a missing portion in the presentation of two professors. So I'd like to share my own uninspired "translation" of what I think was lost from the script/scroll that they might have prepared, or that I wish they had prepared and shared if only they had been given more time.

Excerpts from the "Missing Script"

[Concluding remarks to be made by Brian, if time permits.]Now let me point out that if anything we've said is making you think that the Book of Abraham was just made up and is a fraud, then you are making unwarranted assumptions and need to look at this inspired work of scripture more carefully. What we've addressed are some genuine puzzles to us regarding how the translation was done. But there's much more to the Book of Abraham than just the translation method, for which most of what we have is a question mark.

Indeed, what some of you might be hearing so far in this presentation may sound similar to what many critics of the Book of Abraham have observed long ago: looking at the Kirtland Papers and the Joseph Smith Papyri, it is easy to assume that Joseph Smith and his associates were trying to translate Egyptian in a very strange way, where a single Egyptian character or even a portion of a character could give a paragraph or two of English text. And of course, all the apparent translations in the Kirtland Papers are just wrong and even a bit crazy. So does that mean Joseph Smith was just making stuff up and was dead wrong? Not necessarily, for several reasons.

Just as the apparent problems with the Book of Abraham have been discussed for decades, so, too, have LDS scholars provided evidence, analysis, and alternate theories or frameworks to cope with these problems. Here are some important points and approaches to consider. I may not agree with all of these points, but as a responsible scholar, I need to acknowledge prior scholarship in this field, and the work of faithful LDS scholars like Hugh Nibley, John Gee, Kerry Muhlenstein, Matthew Roper, John Tvedtnes, Michael Rhodes, H. Donl Peterson, Robert F. Smith, and others should be carefully considered.

Regarding the "natural" but possibly incorrect assumption that Joseph was using the pagan Joseph Smith Papyri to create a "translation," here are just some of the points that various LDS scholars have made in their extensive treatments of the well-known problems we rehashed today. We may not agree with every point, but there are some serious arguments might be made to be weighed against rejection of the Book of Abraham as an authentic, ancient, and divinely inspired text:

1. A divine translation may have occurred first, followed by secular attempts to crack Egyptian. While we have pages in the Kirtland Papers with Egyptian characters on the left and translated English text from the Book of Abraham on the right, this does not mean that we are really getting a window into Joseph's translation process, in spite of the title of this presentation. There are good reasons to believe that the translation on those sheets had already been composed, and now somebody was trying after the fact to explore relationships between the Egyptian characters and the text, or add Egyptian for other purposes. For example, analysis of the writing shows that the English text was probably written first, followed by adding the characters on the left. See John Gee, A Guide to the Joseph Smith Papyri (Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2000), pages 21-23. [Note: the color images of the printed book are not in the free online edition which is text only.] Other details strengthen the conclusion that the Kirtland Papers are not at all showing the work of translation in progress. Kerry Muhlenstein explains this well (see Kerry Muhlestein, "Egyptian Papyri and the Book of Abraham: Some Questions and Answers," Religious Educator 11, no. 1 (2010): 91–108):

Supposedly the translator looked at a few characters from the Book of Breathings and derived the Book of Abraham from them.[22] This premise assumes that the characters were written first and that the text written next to them was created afterward as an attempt to translate the characters’ meaning.2. The Kirtland Egyptian Papers may primarily reflect the views of W.W. Phelps, not necessarily Joseph Smith. According to John Gee, “Joseph Smith and Ancient Egypt,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 427–48, the various manuscripts grouped together as the Kirtland Papers are largely from, and came into possession of the Church via, W.W. Phelps, not Joseph Smith:

There are, however, a number of problems with this assumption: (1) Scribal errors and other critical textual clues make it very clear that these papers represent later copies of the text of the Book of Abraham, not the original translation; they were probably not even first- or second-generation copies. Thus the characters at the right were not characters they were trying to work through on these papers; they must mean something else. (2) The Egyptian characters appear to sometimes overwrite the English. If this is the case, then it is clear they were later additions. (3) The first Egyptian characters are written in the order they appear in the Book of Breathings, but some characters in one of the manuscripts skip characters and lines and are even from two different papyri, exhibiting no system or method. It is hard to believe that Joseph thought he was to translate from random parts of the text instead of systematically going from line to line.[23] (4) We have reason to believe that while Joseph Smith was involved in creating some of the Kirtland Egyptian Papers (two of the sixteen pages contain Joseph’s handwriting), at other times his associates did this work without him. The pages whose composition we can date come from a period when the Prophet was out of town and the School of the Prophets seemingly went on without him. Adding up all these scraps of evidence, it seems highly improbable that this collection of papers represents Joseph’s original translation.

So what are these papers? Do they represent an attempt on the part of a group who was very interested in ancient languages to create an Egyptian grammar after Joseph had translated the Book of Abraham? Do the Egyptian figures serve as fanciful and archaic bullet points? Were the Egyptian characters placed beside the text to excite the minds of potential readers in hopes of increasing the book’s circulation? At the present, we do not have enough evidence to discern what these papers represent, but it seems unlikely that they represent an English translation of the Egyptian characters written on the side. The evidence points away from this conclusion. Thus, while we cannot present an answer as to what these papers are, we can say the evidence does not support the critics’ claims.

The vast majority of the manuscripts were brought to Utah by Willard Richards and W. W. Phelps. But one of the documents was given to the Church by Wilford Wood. He in turn obtained it from Charles Bidamon, who, in turn, got it from his father, who was Lewis Bidamon, Emma Smith’s second husband. So we know this document belonged to Joseph Smith. The others did not. To whom did the other documents belong? They arrived at the Church Historian’s Office through Willard Richards and W. W. Phelps. Four of the documents are in the handwriting of Willard Richards and can be safely said to belong to him. Most of the rest of the documents are in Phelps’s handwriting and seem to have belonged to him.Further, the format of these papers reflects what Phelps was already doing in his own project to figure out the "pure language" of Adam, a futile project he started before he ever heard of the Egyptian scrolls. The format, the handwriting, and other details indicate that this was Phelps' project and that the Kirtland Egyptian Papers can best be called a "window into what W.W. Phelps thought," not really a "window into Joseph Smith's translation." Perhaps we might need to, um, revise today's title -- but of course, I recognize you all might not have come today to hear about Phelps' errant views. In any case, John Gee made some interesting points about how these documents actually don't give us a window into Joseph's thinking at all, in his view, and to be fair, here it is from Gee's “Joseph Smith and Ancient Egypt”:

Format. As William Schryver has pointed out, the format of many of the Kirtland Egyptian Papers follows that format established by W. W. Phelps in work he did on the pure language in May 1835 before anyone in the Church had heard of the papyri. All of them are from his collection of manuscripts. Kirtland Egyptian Papers show the influence of his thinking and were begun in his handwriting. They show what W. W. Phelps thought. They include the famous “Grammar and aphabet [sic]” book, which has been incorrectly included as the work of Joseph Smith on the Joseph Smith Papers website.Obviously, since we list 1835 as the date for the Kirtland Egyptian Papers, we don't fully agree with Gee's assessment and his interpretation of transliteration data, but if he is correct, that's a devastating blow to any theory that the Kirtland Papers are somehow a window into Joseph's translation methodology. I think more study of that issue is needed, and if our 1835 date is wrong, of course we'll revise that. I welcome further analysis here.

Contrary to the date provided on the Joseph Smith Papers website, the book cannot date to 1835. How do we know that? The system of transliteration that Phelps used in the book follows the transliteration system taught by Josiah Seixas beginning in January of 1836. Words with long final vowels end in an “h.” The transliteration system used before that does not have the “h” and this can be seen in the transcriptions of the same words made in October 1835. Since the book has the later system, it must date after the later system was taught and thus must date after its introduction in January 1836. Joseph Smith’s journal entries indicate that within a week of receiving Hebrew books, Joseph dropped working on Egyptian in favor of Hebrew.[77]

We have no record of Joseph Smith working on Egyptian materials from November 1835 until the beginning of 1842. Although Joseph Smith’s journals have numerous gaps starting in the spring of 1836, from October 1835 to April 1836, we have good records of what he was doing, and he was working on projects other than studying Egyptian after November 1835. This means that he was not working on the so-called Grammar and Alphabet, with its 1836 transliteration system. That work, instead, should be attributed to the man in whose handwriting it is and whose format it follows: W. W. Phelps.

Journal entries. Joseph Smith’s journal also seems to indicate that the documents in Phelps’s archive belonged to Phelps. After Joseph Smith heard W. W. Phelps read a letter that Joseph Smith had him write for him that quotes from the documents, afterwards Joseph Smith “called again and enquired for the Egyptian grammar.”[78] Yet two days later he “suggested the idea of preparing a grammar of the Egyptian language”[79] apparently because he did not agree with Phelps’s treatment.

Thus the provenance, the format, and Joseph Smith’s treatment in his journals indicate that the majority of the Kirtland Egyptian Papers belonged to Phelps. So they cannot be used to reconstruct Joseph Smith’s knowledge of Egyptian, only that of W. W. Phelps. [emphasis added]

3. Facsimile 1 was not necessarily attached next to the text Joseph called the Book of Abraham. Some argue that Facsimile 1 being attached to a version of the Book of Breathings in the Joseph Smith Papyri does not necessarily mean that the text Joseph was seeking to translate was the Book of Breathings. Kerry Muhlenstein, in fact, argues that in the time and place where Joseph's papyrus collection originated in Egypt, vignettes on a scroll often were not placed directly with the text they were related to. It could have been in another portion of a long scroll containing an Abrahamic section, for example. Several scholars have made similar arguments. Here's an excerpt from Kerry Muhlestein's "Egyptian Papyri and the Book of Abraham: Some Questions and Answers":

To begin with, we must ask if vignettes are always associated with the adjacent text in other Egyptian papyri from this time period. We know with some degree of precision the dating of the Facsimile 1 papyrus (also known as Joseph Smith Papyrus 1, or JSP 1), because we know exactly who the owner of this papyrus was. He lived around 200 BC and was a fairly prominent priest in Thebes.[4] (Incidentally, this priest is not alone as a practitioner of Egyptian religion who possessed or used Jewish religious texts. We can identify many others, particularly priests from Thebes).[5] During this period, it was common for the text and its accompanying picture to be separated from each other, for the wrong vignette to be associated with a text, and for vignettes and texts to be completely misaligned on a long scroll.[6] Frequently there is a mismatch between the content of a vignette and the content of the text, or the connection is not readily apparent.[7] This is particularly common in Books of Breathings, the type of text adjacent to Facsimile 1 on the Joseph Smith Papyri.[8] Incongruity between texts and adjacent vignettes is endemic to papyri of this era.[9] Thus, the argument that the text of the Book of Abraham had to be translated from the hieroglyphs next to the vignette is not convincing when compared with ancient Egyptian texts from the same period.Also see Dr. Muhlestein's discussion in "Assessing the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Introduction to the Historiography of their Acquisitions, Translations, and Interpretations," Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 22 (2016): 17-49.

4. The descriptions of the scroll Joseph was translating, based on eyewitness reports, do not match the surviving Joseph Smith Papyri. Hugh Nibley, of course, has made this point at length, as has John Gee and many others. Even amateur apologists can provide help on this issue, but first see, for example, Kerry Muhlestein, “Egyptian Papyri and the Book of Abraham: A Faithful, Egyptological Point of View,” in No Weapon Shall Prosper: New Light on Sensitive Issues, ed. Robert L. Millet (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 217-43.

5. The Joseph Smith Papyri form only a small portion of the collection of scrolls Joseph Smith had. There is no doubt that significant documents other than the surviving fragments were sold to a museum. These were presumably were destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire. This at least raises the possibility that the missing documents could have dealt with Abraham. For some details, see John Gee, A Guide to the Joseph Smith Papyri.

6. Significantly, the scrolls Joseph had came from the precise time and specific place where Egyptian interest in Hebrew texts and figures like Abraham was high, making it possible for something like the Book of Abraham to have been in that collection. John Gee treats this in detail in his useful book, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Religious Studies Center, 2017).

Ancient Roots and Modern Evidence

LDS scholars have proposed several theories for how the translation may have been done, besides the antagonistic view that "Joseph was just making stuff up and got everything wrong as he worked with pagan materials that had nothing to do with Abraham." Those other views include (1) translation from a now missing scroll that contained the Book of Abraham, or (2) revelation largely independent of whatever was on the scrolls, perhaps "catalyzed" by the scrolls, restoring an ancient document. But regardless of how the translation was done and what specific relationship it has to any of the scrolls, whether missing or surviving, analysis of the text and the facsimiles raises many issues that point to ancient content that would be beyond Joseph's abilities to fabricate.

One important source of such evidences comes from a publication that I edited with John Gee: Traditions about the Early Life of Abraham, edited by John Tvedtnes, Brian Hauglid, and John Gee. In that volume, we compiles many dozens of ancient documents from Jewish, Christian, and Muslim sources that support many of the elements in the Book of Abraham that are not found in the Bible and would have been highly unlikely for Joseph Smith to have known of. Most of these documents were not known in Joseph's day or at least not translated into English. And while one detail, that of Abraham talking about astronomy, can be found in one part of the extensive writings of Josephus, there is no evidence that Joseph had access to Josephus when he began the translation of the Book of Abraham, making it unlikely that he knew this tiny detail.

Regarding the sacrifice of Abraham, while many ancient traditions speak of it, the long-standing consensus of scholars has been that human sacrifice was pretty much unknown in the peaceful society of ancient Egypt, raising serious questions about the key story that opens the Book of Abraham. I say "has been" regarding that consensus, but this apparent consensus has been shaken now in light of abundant data that ritual violence was in fact practiced in Egyptian religion and for precisely the kind of issues suggested in the Book of Abraham. What was once a glaring weakness in the Book of Abraham is now one of its many strengths.

The key work that has overturned the consensus came from the Ph.D. study of Kerry Muhlestein, now a professor here at BYU. This work led to a scholarly book: Violence in the Service of Order: The Religious Framework for Sanctioned Killing in Ancient Egypt (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2011), which is available at Amazon, distributed by BAR Publishing, provided at Academia.edu, or can be directly downloaded for free online. It's a thorough and fascinating book that fills a gaping weakness in our understanding of ancient Egypt and also shows that ritual sacrifice of a religious rebel like Abraham, an opponent of idol worship, would, in the time of Abraham and in a place under Egyptian control, be highly plausible. A more recent scholarly publication on this topic is his “Sacred Violence: When Ancient Egyptian Punishment was Dressed in Ritual Trappings,” Near Eastern Archaeology, 78/4 (2015): 229-235, where he finds that from the Old Kingdom through the Libyan era of ancient Egypt, “disturbing either the divine or funerary cult is the most likely crime to elicit ritual slaying as punishment.” Also see his paper, "Royal Executions: Evidence Bearing on the Subject of Sanctioned Killing in the Middle Kingdom," in The Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 51/2 (2008): 181-208.specifically on the Middle Kingdom, especially relevant for the Book of Abraham.

It turns out that there are numerous details in the Book of Abraham that are suggestive of ancient, mot modern origins. While some things Joseph says about, say, the Facsimiles, are puzzling to us, some are simply bulls-eyes such as properly identifying the four upside-down figures on Facs. 2, labeled as figure #6, as the "four quarters of the earth," an entirely appropriate description of the four sons of Horus who take messages to the four quarters of the earth and who each represent a cardinal direction. There are many other strengths to consider in the statements Joseph makes about the facsimiles. Some of these strengths were once glaring weaknesses. For example, one can ask why the Egyptians would care about Abraham, a Hebrew foreigner, and claim that the Egyptians don't have ancient texts dealing with him. But now we know of multiple examples of Egyptian documents that involved Abraham in some way (including from the time and place where Joseph Smith's collection of scrolls came from, the region of Thebes around 200 B.C.), and in ways that are consistent with some aspect of the Book of Abraham. See John Gee, "Research and Perspectives: Abraham in Ancient Egyptian Texts," Ensign, July 1992 and Kerry Muhlestein's above-mentioned “Egyptian Papyri and the Book of Abraham: A Faithful, Egyptological Point of View.”

Facsimile 1, with its scene of attempted sacrifice by a priest and supplication by Abraham, has long been dismissed by supposed experts as merely an ordinary funerary scene depicting the embalming of a corpse. Clearly it is related to many ordinary funerary scenes, but it has been adapted in an unconventional way. The figure on the lion couch is clearly alive! His legs are up. He is not wrapped or naked, as in typical funerary scenes. And as for the the notion that Abraham prayed upon the altar to be delivered as we read in Abraham 1:15 there's something you need to notice when you see this allegedly ordinary embalming scene that truly gives it a "leg up" on the competition.

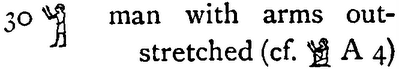

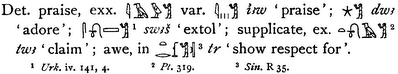

Significantly, the person with the raised arms and extended leg is drawn in the exact posture used for the hieroglyph meaning "to pray" or "to supplicate," but rotated 90 degrees to be on the table or altar. The drawing is clearly and deliberately intended to depict a live person PRAYING - just as the Book of Abraham suggests. It's even drawn with the right orientation (head to the right) so that simply rotating the figure 90 degrees counterclockwise yields the easily recognized glyph (instead of being upside down).

For evidence, turn to the highly respected work of Sir Alan Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar, Being An Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, 3rd Ed. (Oxford University Press, London: 1966), p. 32, paragraph 24, where we find this (many thanks to Stan Barker for sending these figures):

and

The glyph above for death shows a figure depicted in the normal manner for funerary scenes: clearly immobilized and wrapped up, quite unlike the most unusual depiction in the Book of Abraham. A couple of other portions of Gardiner are also relevant. The figure below comes from Gardiner, page 445, paragraph 30:

The man with outstretched arms is used in the following excerpts to help convey prayer, praise, and supplication:

Joseph Smith's interpretation of the figure makes a lot more sense than that of his learned critics.

Joseph Smith's interpretation of the figure makes a lot more sense than that of his learned critics. In terms of the text itself, there are numerous issues that defy the notion that Joseph just made up the Book of Abraham based on what little he knew at the time. One of many examples is the name and location of a place mentioned in Abraham 1:10, Olishem. It turns out that there is in fact such a place name from the ancient Levant in a plausible location. Here is what John Gee writes in An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Religious Studies Center, 2017), pp. 98, 101:

Biblical scholars have not agreed on the time and place that Abraham lived, but the Book of Abraham provides additional information that specifies both. In the Bible, Abraham must flee his homeland (môladâ) in Ur of the Chaldees (Genesis 12:1). Later he sends his servant back to his homeland (môladâ) to find a wife for his son (Genesis 24:4, 7). The servant is sent to Aram-Naharaim in modern-day northern Syria or southern Turkey (Genesis 24:10) and not Mesopotamia as the King James translators rendered it. This location of Aram-Naharaim must have been the location of Abraham's homeland. The Book of Abraham also indicates that Abraham's homeland was in that area. Olishem (Abraham 1:10), one of the places mentioned near Ur, appears in Mesopotamian and Egyptian inscriptions in association with Ebla, which is in northern Syria. (pp. 98, 101)Many readers may not notice how interesting or even sensational this issue may be. It was already interesting when Akkadian documents were noted that mentioned the place Olishem, and it got much more interesting when a Turkish team reported finding the site and noted that ancient documents indicate this was place where Abraham had lived. See the press release "Prophet Abraham's lost city found in Turkey's Kilis" in The Hurriyet Daily News, August 16, 2013. On this matter, Gee has elsewhere noted the potential value but urges patience as more work is needed. See John Gee, "Has Olishem Been Discovered?," Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22/2 (2013): 104–7.

Finding the place name Olishem was interesting enough in many ways before the actual archaeological site was found and its connection to Abraham made. In a rather technical 2010 post, Val Sederholm explores the significance of Olishem and related Egyptian and Semitic words in "The Plain of Olishem and the Field of Abram: LDS Book of Abraham, Chapter One," I Begin to Reflect, April 27, 2010. "Is the place of Ulisum or Olis(h)em the plain of Olishem? Conclusions remain premature, but it would be remiss not to point out the similarity and, by so doing, show that the Book of Abraham merits a second look." Sederholm then explores the rich association of meanings related to Olishem that may make it an entirely appropriate name for a place with a hill, suggesting the possibility not only of a phonetic connection between the Akkadian account and the Book of Abraham, but also a semantic connection. Indeed, there are many such fascinating issues in the Book of Abraham, leading Sederholm to make a strong but supportable statement:

Exactly how does a book of 14 pages produce dozens upon dozens of linguistic, cultural, thematic, theological, and literary points of comparison to the Ancient Near Eastern record? The numbers are no exaggeration. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, with no hesitation whatsoever, not even a hint of abatement, continues to post the canonical Book of Abraham on line and to print copies by the tens of thousands in scores of languages. There is a lot of explaining to do.These issues include:

- Abraham's opposition to idol worship, supported now by numerous ancient documents, many of which mention the resulting attempted punishment of being sacrificed and some of which mention that his own father had become an idol worshiper, as taught in the Book of Abraham.

- The use of an ancient astronomical model implicit in the astronomical model that Abraham used in teaching Pharaoh, coupled with an apparent Egyptian wordplay or two, as John Gee has described in his book.

- Identifying the crocodile in Facs. 1 as the god of Pharaoh. See Quinten Barney, "Sobek: The Idolatrous God of Pharaoh Amenemhet III," Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22/2 (2013): 22–27. Also see "The Crocodile God of Pharaoh in Mesopotamia," FARMS Update No. 108, in Insights 16/5 (Oct. 1996), p. 2, and other sources as well.

- The plausibility of many aspects of the Book of Abraham in light of what we can determine about the ancient setting treated in the text. See, for example John Gee and Stephen D. Ricks, “Historical Plausibility: The Historicity of the Book of Abraham as a Case Study,” in Historicity and the Latter-day Saint Scriptures, ed. Paul Y. Hoskisson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2001), 63–98.

- Possible evidence for the authenticity of several names in the Book of Abraham. For a wide-ranging discussion, see the transcript of John Tvedtnes, "Ancient Names and Words in the Book of Abraham and Related Kirtland Egyptian Papers," 2005 FAIR Conference, August 5, 2005. (See the links on the final page to watch the presentation on YouTube.)

- The Book of Abraham's cosmology and the theme of the divine council which fit remarkably well in the world of the ancient Near East, as detailed, for example, in Stephen Smoot's "Council, Chaos, and Creation in the Book of Abraham."

- John Gee and Stephen D. Ricks, “Historical Plausibility: The Historicity of the Book of Abraham as a Case Study,” in Historicity and the Latter-day Saint Scriptures, ed. Paul Y. Hoskisson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2001), 63–98.

- John Gee, “Joseph Smith and Ancient Egypt,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 427–48.

- Kerry Muhlestein, "Egyptian Papyri and the Book of Abraham: Some Questions and Answers," Religious Educator 11, no. 1 (2010): 91–108. (PDF also available.)

- Kerry Muhlestein, "Joseph Smith and Egyptian Artifacts: A Model for Evaluating the Prophetic Nature of the Prophet's Ideas about the Ancient World,"

Given the rich evidences of ancient influence in the Book of Abraham, it is fair to recognize that something is going on in this story that is clearly beyond random guesses from Joseph Smith. It is a powerful account rich in beautiful doctrine that demands respect. When Latter-day Saints and our investigators become upset about some of the puzzling aspects around the Book of Abraham, it is inevitably due to expectations that aren't entirely reasonable. We cannot expect that every detail about the papryi and the mummies were instantly revealed or ever revealed to Joseph Smith. His translation, however made, was a work in progress and he did not live to see it through to completion and canonization. It is entirely possible that during this project, he brought many of his own ideas to the work as he steadily gained revelation and new insights. Amid the jewels he has given us, if there is a peripheral statement that currently seems wrong or unintelligible to us, let us be patient and not fall apart. Kerry Muhlestein explains that when we look at how other revelations such as the doctrine of baptism for the dead came, it seems to have been a process that took time for Joseph to winnow out his own thoughts from revelation and gradually come to a finished work ready to be promoted among the Saints as doctrine. There may have been a similar process going on with the Book of Abraham that was cut short by his death. See Kerry Muhlestein, "Joseph Smith and Egyptian Artifacts: A Model for Evaluating the Prophetic Nature of the Prophet's Ideas about the Ancient World," BYU Studies 55/3 (2016): 35-82.

There are other questionable assumptions that people bring to these issues when they consider the relationship of our text, the Egyptian scrolls, and the life of Abraham. Do we require the Book of Abraham text to be a document exactly as written or dictated by Abraham, including the facsimiles? Or do we recognize that like much of scripture, the original documents and accounts can go through a process of transmission over time that may introduce anachronisms or or other puzzles? Do we expect that Joseph's comments on the facsimiles must be what Abraham meant to convey? Do we expect it to be what an Egyptian in 200 B.C. might have understood when applying those figures to Abraham's story? Or could it be what a Jew in that time familiar with Egyptian themes might have understood or wished to convey? Or do we take it as what Joseph and/or the Lord wanted us to understand from those figures as applied to the Book of Abraham? These issues are complicated. Please don't let simple statements from anyone, myself included, shake you up based on a clash with a possibly unrealistic or naive assumption that you may have. Marvel at the miracle of the Book of Abraham and the Book of Mormon, but don't fall apart when facing a problem. Study these issues out with patience, with flexibility, and with the help of the abundant evidences that something fascinating and something worthy of respect and ongoing study is going on in these scriptures.

Thank you for being here today!

Other Resources:

- Hugh Nibley, An Approach to the Book of Abraham (Provo, UT: Maxwell Institute Publications, 2010, orig. publ. 1957).

- Michael Ash and Kevin Barney, "The ABCs of the Book of Abraham," 2004 FAIRMormon Conference.

- John Gee, A Guide to the Joseph Smith Papyri (Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2000), [See the actual book for the color images that are especially useful.]

- Kerry Muhlestein and Megan Hansen, “'The Work of Translating': The Book of Abraham's Translation Chronology,” in Let Us Reason Together: Essays in Honor of the Life’s Work of Robert L. Millet, ed. J. Spencer Fluhman and Brent L. Top (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: 2016), 139–62. The authors argue that by the end of 1835 Abraham 4-5 had already been translated. Hebrew words may have been added to the text later as a gloss to incorporate words learned during Joseph's later study of Hebrew.

- Kerry Muhlestein, "Papyri and Presumptions: A Careful Examination of the Eyewitness Accounts Associated with the Joseph Smith Papyri," Journal of Mormon History 42/4 (October 2016):31-50; https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/jmormhist.42.4.0031.

- Kerry Muhlestein, "Joseph Smith and Egyptian Artifacts: A Model for Evaluating the Prophetic Nature of the Prophet's Ideas about the Ancient World," BYU Studies 55/3 (2016): 35-82.

- FAIRMormon.org's pages on the Book of Abraham, including issues such as Questions on Facsimile 1.

- Kerry Muhlestein, "Assessing the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Introduction to the Historiography of their Acquisitions, Translations, and Interpretations," Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 22 (2016): 17-49.

- Kerry Muhlestein, “Egyptian Papyri and the Book of Abraham: A Faithful, Egyptological Point of View,” in No Weapon Shall Prosper: New Light on Sensitive Issues, ed. Robert L. Millet (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 217-43.

- Rabbi Nissim Wernick, A Critical Analysis of the Book of Abraham in the Light of Extra-Canonical Jewish Writings, Ph.D. dissertation, BYU, 1968.

- Michael D. Rhodes, "The Joseph Smith Hypocephalus: Twenty Years Later." This article provides an excellent discussion of Facsimile #2 and the commentary of Joseph Smith.

- Robert F. Smith, "A Brief Assessment of the Book of Abraham," Version 10, March 21, 2019; https://www.scribd.com/document/118810727/A-Brief-Assessment-of-the-LDS-Book-of-Abraham.

- The Book of Abraham Project - a project at BYU dealing with the documents and criticisms of the Book of Abraham. See, for example, the page "Criticisms of Joseph Smith and the Book of Abraham."

- John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid, editors, Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant: Proceedings of the 1999 Book of Abraham Conference (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005); https://publications.mi.byu.edu/book/astronomy-papyrus-and-covenant/. See especially the chapters of Kevin L. Barney, “The Facsimiles and Semitic Adaptation of Existing Sources,” and John Gee, “Facsimile 3 and Book of the Dead 125.”

This post is part of a recent series on the Book of Abraham, inspired by a frustrating presentation from the Maxwell Institute. Here are the related posts:

- "Friendly Fire from BYU: Opening Old Book of Abraham Wounds Without the First Aid," March 14, 2019

- "My Uninspired "Translation" of the Missing Scroll/Script from the Hauglid-Jensen Presentation," March 19, 2019

- "Do the Kirtland Egyptian Papers Prove the Book of Abraham Was Translated from a Handful of Characters? See for Yourself!," April 7, 2019

- "Puzzling Content in the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar," April 14, 2019

- "The Smoking Gun for Joseph's Translation of the Book of Abraham, or Copied Manuscripts from an Existing Translation?," April 14, 2019

- "My Hypothesis Overturned: What Typos May Tell Us About the Book of Abraham," April 16, 2019

- "The Pure Language Project," April 18, 2019

- "Did Joseph's Scribes Think He Translated Paragraphs of Text from a Single Egyptian Character? A View from W.W. Phelps," April 20, 2019

- "Wrong Again, In Part! How I Misunderstood the Plainly Visible Evidence on the W.W. Phelps Letter with Egyptian 'Translation'," April 22, 2019

- "Joseph Smith and Champollion: Could He Have Known of the Phonetic Nature of Egyptian Before He Began Translating the Book of Abraham?," April 27, 2019

- "Digging into the Phelps 'Translation' of Egyptian: Textual Evidence That Phelps Recognized That Three Lines of Egyptian Yielded About Four Lines of English," April 29, 2019

Continue reading at the original source →