There are three documents from the Kirtland Egyptian Papers that have a portion of the English translation (ranging from Abraham 1:4 to 2:18), each with a few Egyptian symbols or portions of symbols to the left. Some have argued that this shows Joseph's translation process at work, revealing his foolish belief that mystic Egyptian writing contained intricate details magically condensed into a few strokes. First, it's hard for me to believe that Joseph could have believed such a thing were possible, especially when the "Reformed Egyptian" script on at least much of the gold plates gave no hint of such miraculously compact text. Had it been that way, a single gold leaf might have held the entire Book of Mormon or more, but it was a fairly thick book based on witness accounts, and while 2/3 of it was sealed, that still gives a plausible amount of surface area for engraving the text of the Book of Mormon in small Hebrew characters, and certainly enough for a slightly more compact script. See my LDSFAQ answer to the question, "How could the whole Book of Mormon fit on the small number of unsealed gold plates?" But ignoring for now the clear disconnect between Joseph's prior translation work with Reformed Egyptian and the KEP translation theory, let's consider Gee's arguments and the KEP manuscripts. In Chapter 3 of his book, pages 21-23, he writes:

According to this theory, the text to the right is the translation of the Egyptian characters to the left. Unfortunately for this theory, the Egyptian characters were added after the entire English text was written (as evidenced by the use of different inks, Egyptian characters that do not always line up with the English text, and Egyptian characters that sometimes overrun the English text). Thus it was not a matter of writing the character and then writing the translation but of someone later adding the characters in the margin at the beginning of paragraphs of text without explicitly stating the reason for doing so.

Advocates of the Kirtland Egyptian Papers theory also assume that Joseph Smith first compiled a grammar from which he then produced the translation. But when a text in an unknown language is initially translated, a decipherer usually cracks the language without the use of grammars. Grammarians then go through the translation, establish the grammatical usage, and compile a grammar. Later, individuals learn the grammar and then produce translations. As a decipherer and one who had never formally studied any grammar at the time he produced the translation, Joseph Smith would have done the translation first.

The Kirtland Egyptian Papers that have been connected with the papyri appear to be a later attempt to match up the translation of the Book of Abraham with some of the Egyptian characters (see examples on opposite page). If one assumes that the Book of Abraham was the second text on the papyrus of Hor, a possible scenario is that having the translation of the Book of Abraham, the brethren at Kirtland tried to match the Egyptian characters with the translation but chose the characters from the first text. Yet it is not certain that this is what they thought they were doing.

He shows six examples of color images from the KEP that are said to demonstrate the use of different inks, characters that don't line up with the text they are supposedly generating, and characters that overrun the vertical line separating the characters from the English text. The images unfortunately are somewhat small and not in high resolution, and the online version of the book only has the text, not images.

I should also note that Gee and others elsewhere have also observed that other clues such as scribal errors in the English translation further suggest that in these manuscripts, an already existing English translation was copied down, not generated. Thanks to the Joseph Smith Papers, we can now look at the KEP documents up close and better evaluate such arguments ourselves. Below are some of the features that I suggest should be considered.

Turning to the Table of Contents for Volume 4 of the Joseph Smith Papers, we can see that there are links to the three key documents in question. These are:

- Document A: "Book of Abraham Manuscript, circa July–circa November 1835–A [Abraham 1:4–2:6]"

- Document B: "Book of Abraham Manuscript, circa July–circa November 1835–B [Abraham 1:4–2:2]"

- Document C: "Book of Abraham Manuscript, circa July–circa November 1835–C [Abraham 1:1–2:18]"

One more clue to consider up front is that these documents clearly cover only a small portion of the Book of Abraham, not the entire text. The most coverage is found in Document C which has English text from Abraham 1:1 to 2:18, representing less than 2 of the 5 chapters of the text. But let's now look at the images.

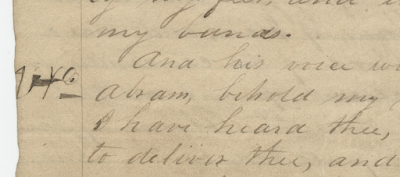

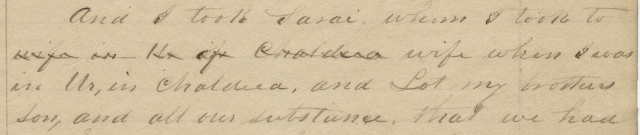

Here is Sample 1 from Gee, taken from the top of page 8 of Document C. Here the Egyptian characters overrun the vertical dividing line. Some have assumed that the English is indented to avoid the Egyptian character, but indentation is common throughout for new verses or other purposes, and when Egyptian characters are placed on the text, that are often near or aligned with these natural breaks. In the caption to his photos on page 22, Gee cites this as an example where not only does the Egyptian text run over the margins, but also runs over the English text. I assume he means that the Egyptian text here extends well past the leftmost margin of the English text, rather than meaning that it overwrites any English text.

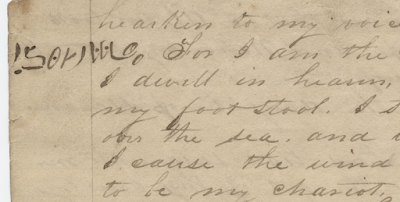

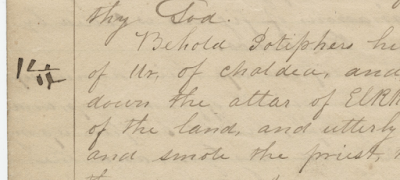

An example not mentioned by Gee is readily noted on page 1 of Document A, where Egyptian again overruns the vertical dividing line, as if a dividing line were drawn for the English text on the page first, and then Egyptian was filled in, not always with enough space. Here the word "utterly" to the right appears slightly indented, but no more than the text two lines later. Indeed, most of the lines on that sheet are indented about the same amount as "utterly."

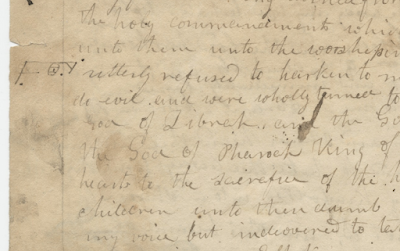

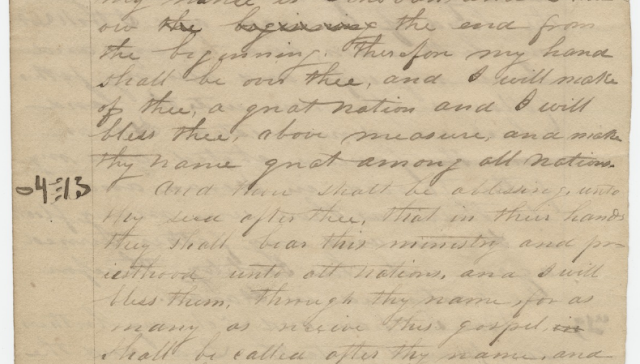

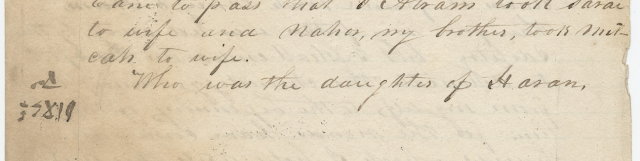

The top of this sheet, shown below, shows some of the corrections made in copying this text. Interestingly, both Documents A and B have a correction made in Abraham 1:4, with "I sought for the appointment whereunto the priesthood" changed to "I sought for mine appointment unto the priesthood," the wording used in Document C. Document C has the broadest expanse of text and thus if one of these were the original source for the Book of Abraham, Document C might be the most logical candidate.

Another example from Gee comes from page 2 of Document A, which is Sample 4 in Gee. This is cited as an example of different ink being used in the Egyptian than in the English, of text that runs over the margin line, and of text that does not line up with the English. Here I cannot be sure that the ink is different, for it may simply be that it has been more heavily applied in the heavy drawing on the left. Anyone up for some non-destructive chemical analysis? I'd love to have something more specific on the inks used. As for going over the margin, the degree of overrun is minor. On this page, though, two of the three Egyptian characters slightly overrun the margin line. If the margin line were drawn after the first couple of characters had been put down, one might expect it to be drawn to the right of the characters (ditto for page 1, discussed above). In general, though, it does seem reasonable that the margin line was drawn following the addition of the English text, and then came the Egyptian. There is misalignment with the beginning of Abraham 1:20 ("Behold, Potiphar's Hill was in ..."), but the Egyptian is only slightly elevated, so it's not serious misalignment.

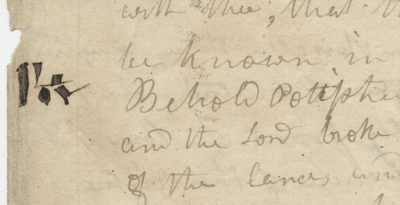

The next example from page 3 of Document A shows slight overlap of Egyptian with the margin. But it also shows that a single ink (so I presume) used for the Egyptian can create the appearance of darker ink by applying the ink more heavily, as I believe has happened here. This is not one of the examples shown by Gee, though.

The image below is taken from page 5 of Document B, corresponding to Sample 2 of Gee, which is said to show different ink and margin overrun in the Egyptian. The overrun is clear, but I'm not sure about the ink.

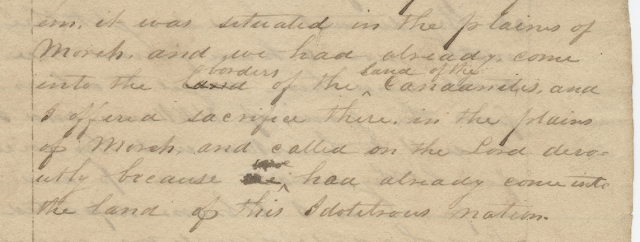

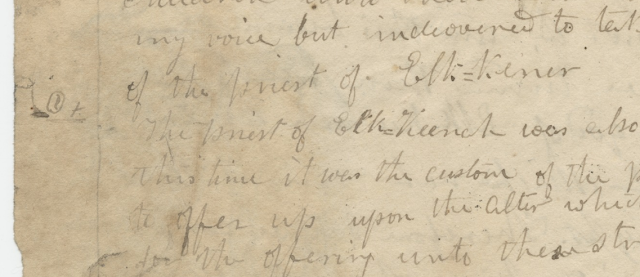

Next is an image from page 3 of Document C, corresponding to Sample 3 of Gee, said to show the use of different ink and also said to demonstrate Egyptian that does not line up with the English text. Again, I'm not sure on the ink, though it may be different. As for the alignment, I tend to agree. If the Egyptian had been written first followed by the production of an English translation, the indented beginning of a verse would presumably be directly to the right of the Egyptian. It makes sense that the Egyptian was added later in Document C, which is clearly the best candidate (however inadequate) of the three documents for the source of the Book of Abraham for those advocating the KEP theory for how the translation might have been done.

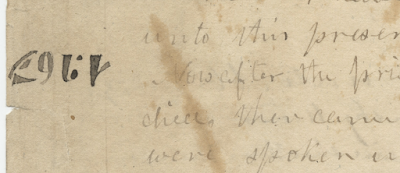

The following image is from page 4 of Document C, corresponding to Sample 6 of Gee, said to show different ink and misalignment of Egyptian with the English. The ink does appear different but I'm not sure The alignment is much worse than the same text from page 2 of Document A discussed above, making this a clear example of the misalignment problem mentioned by Gee.

Here is an example of a possible change in ink or at least a change in scribe during the copying of text, from page 8 of Document C.

Here is an example of the scribal errors made and corrected in the copying process from page 10 of Document C.

Scribal errors are also visible on page 9 of Document C.

Here is another example of poorly aligned text from page one of Document A.

Document A at page 4 ends with a strange duplicate section where Abraham 2:3 to 2:5 is repeated, and the text begins going all the way to the left side of the page.

Document B at page 6 suddenly ends with an "untranslated" character.

So why the Egyptian characters on these documents at all? Were they there for decoration? Was someone trying to find some mystic relationship between the Sensen text and the Book of Abraham text that came from a missing part of the same scroll? Was W.W. Phelps looking for clues to the pure Adamic language? Much to speculate on, but I don't think it's fair to describe these documents as some kind of window into how Joseph Smith created the English text of the Book of Abraham.

Note: Also see my later post of April 15, "The Smoking Gun for Joseph's Translation of the Book of Abraham, or Copied Manuscripts from an Existing Translation?"

This post is part of a recent series on the Book of Abraham, inspired by a frustrating presentation from the Maxwell Institute. Here are the related posts:

- "Friendly Fire from BYU: Opening Old Book of Abraham Wounds Without the First Aid," March 14, 2019

- "My Uninspired "Translation" of the Missing Scroll/Script from the Hauglid-Jensen Presentation," March 19, 2019

- "Do the Kirtland Egyptian Papers Prove the Book of Abraham Was Translated from a Handful of Characters? See for Yourself!," April 7, 2019

- "Puzzling Content in the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar," April 14, 2019

- "The Smoking Gun for Joseph's Translation of the Book of Abraham, or Copied Manuscripts from an Existing Translation?," April 14, 2019

- "My Hypothesis Overturned: What Typos May Tell Us About the Book of Abraham," April 16, 2019

- "The Pure Language Project," April 18, 2019

- "Did Joseph's Scribes Think He Translated Paragraphs of Text from a Single Egyptian Character? A View from W.W. Phelps," April 20, 2019

- "Wrong Again, In Part! How I Misunderstood the Plainly Visible Evidence on the W.W. Phelps Letter with Egyptian 'Translation'," April 22, 2019

- "Joseph Smith and Champollion: Could He Have Known of the Phonetic Nature of Egyptian Before He Began Translating the Book of Abraham?," April 27, 2019

- "Digging into the Phelps 'Translation' of Egyptian: Textual Evidence That Phelps Recognized That Three Lines of Egyptian Yielded About Four Lines of English," April 29, 2019

- "Two Important, Even Troubling, Clues About Dating from W.W. Phelps' Notebook with Egyptian "Translation"," April 29, 2019

- "Moses Stuart or Joshua Seixas? Exploring the Influence of Hebrew Study on the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language," May 9, 2019

Continue reading at the original source →