The Know

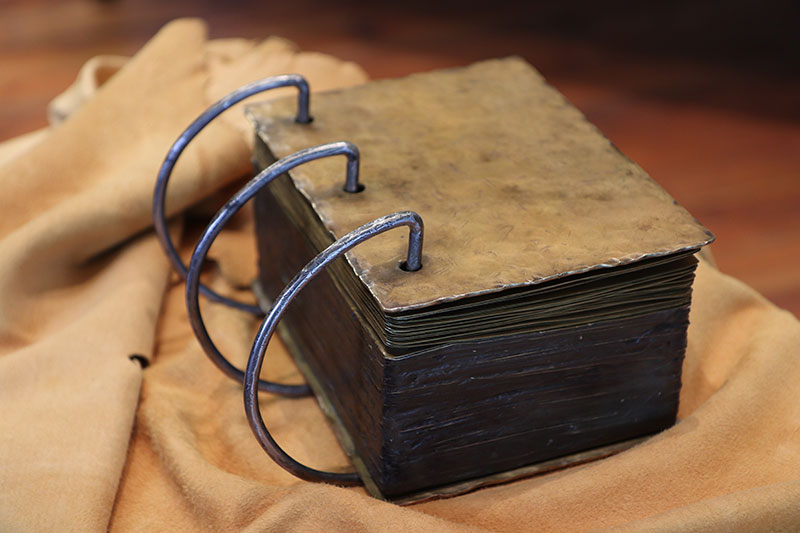

One of the most distinctive aspects of the Book of Mormon is its physical form. Those who saw the ancient Nephite record described it as being engraved onto thin golden plates which were bound together with D-shaped rings.1 The book also mentions other metal records, such as the Brass Plates, the 24 gold plates which contained a Jaredite record, and the underlying Nephite records from which Mormon created his abridgment.2 Clearly, the Nephites had an extensive and enduring tradition of keeping records on metal plates.3 Explaining the reason for their manner of record keeping, the prophet Jacob declared, “whatsoever things which we write upon anything save it be upon plates must perish and vanish away” (Jacob 4:2).

According to H. Curtis Wright, a bibliographer with expertise in ancient epigraphy,4 “literally thousands of metal documents”—written on metals such as lead, bronze, copper, silver, and gold—have been discovered “all over the ancient world.”5 So, the medium upon which the Book of Mormon was written is well attested in antiquity. Yet some may wonder, more specifically, how closely the Book of Mormon and the various plates, which it mentions, resemble other metal documents from the ancient world.

Some Striking Similarities

In several ways, the Book of Mormon bears striking similarities with other samples.6 For example, like the Book of Mormon, other ancient metal documents are known (or were reported anciently) to have been

- written on plates made of gold (or gold alloy),7

- protected by angelic guardians,8

- buried in boxes (some of which were made of stone),9

- bound together with rings (some of them D-shaped),10

- doubled (meaning a similar or identical backup copy was created),11

- sealed in some manner,12

- and authenticated by witnesses.13

Place, Time, Genre, and Script

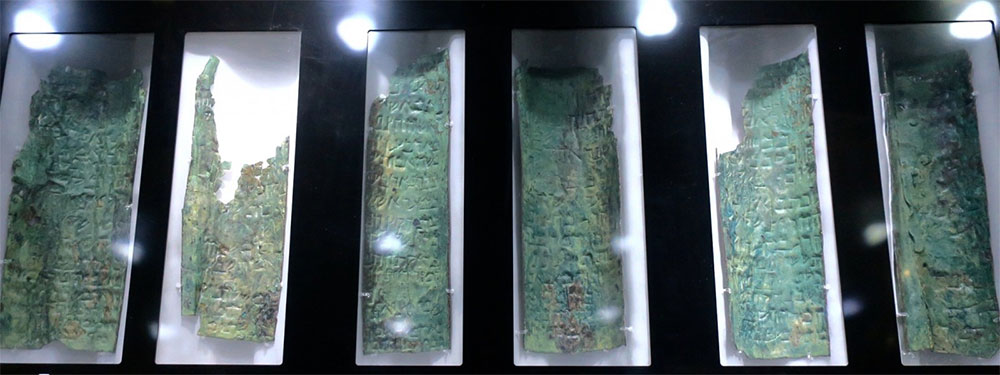

The Copper Scroll from Qumran Cave 3, The Jordan Museum, Amman, Jordan Hashimite Kingdom. Image via the National Catholic Register.

William J. Hamblin, a scholar of ancient history, found that the genres of writing on metal in the “Mediterranean world at the time of Lehi” generally fit into the following categories: ritual, laws, prophecies, and histories.14 “These genres,” wrote Hamblin, “broadly match the described contents of the bronze [brass] plates in the Book of Mormon” (see 1 Nephi 5:11–13), which reflect “the Law (torah), the Prophets (nevi’im), and the Writings (ketuvim)” found in the Jewish tradition.15

Hamblin has also noted that metal documents from the regions of the Mediterranean have been written in various Semitic scripts (including Hebrew), as well as adapted forms of Egyptian.16 This gives a plausible ancient context for the Nephites’ perpetuation of Hebrew and what they called “reformed Egyptian” in their metal record keeping tradition (see Mormon 9:32–33).

Length

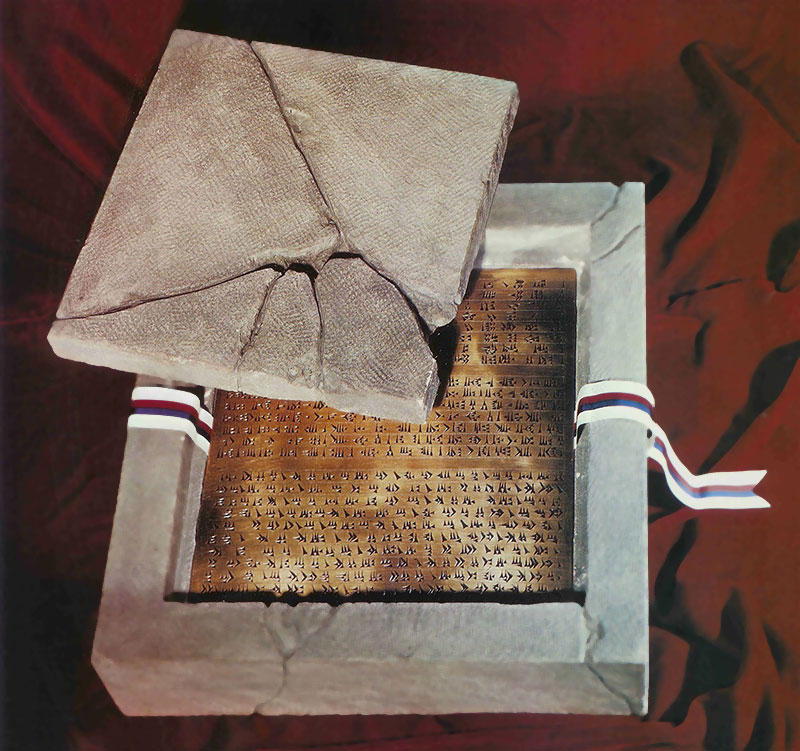

Apadana foundation plates of Darius the Great in a stone box from Tehran, Iran. Image via In the Cavity of a Rock.

When it comes to length, the Book of Mormon is rather unique. Its ancient engravings were translated into over 500 pages of English text. In contrast, the amount of text found on most other known metal documents is quite short, often requiring a few pages or less when translated into English.17

Lengthier ancient metal documents, however, are not completely unheard of. In South Korea, a prophetic record of wisdom teachings was found on a set of 19 gold plates that date to the 8th century AD.18 Even more notable, a gold document, which records “a significant portion of the Quran” was found in the tomb of a Chinese emperor. Its “120 gold gilded plates” were “hinged together” in “6 separate sets of 20 ‘pages.’”19

An eastern philosophical work called The Perfection of Wisdom Sutra is also said to have been written on gold plates. According to David B. Honey and Michael P. Lyon, the text’s “6,400,000 Chinese characters” occupy “three full Western-style volumes in its modern critical edition.”20 Assuming the report of its ancient existence is accurate, “copying it on gold plates must have necessitated an extraordinary amount of gold as well as a huge investment in human and monetary resources.”21

There is an ancient eyewitness report that a Greek poem from around the 8th century BC, called Works and Days, was recorded in a lead book.22 Wright described the poem as a “literary opus of some thirty Oxford pages.”23 An ancient Hittite account, called the Deeds of Suppiluliuma, dating to the 14th century BC, was likely written on bronze tablets.24 Although many sections of the document are poorly preserved, the remaining portions suggest it would have been quite long.

Even closer to Jerusalem, the famous Copper Scroll (part of the Dead Sea Scrolls) is a substantial Hebrew document that dates to the 1st or 2nd century AD. It was inscribed onto separate copper plates that were riveted together into two continuous scrolls.25 These and other examples demonstrate that lengthy metal documents, while rare, are certainly attested in the ancient world.26

Physical Space on the Plates

Silver scroll found at Ketef Hinnom containing a portion of Numbers 6, dating to the 6th or 7th century B.C. Image via the Israel Museum.

Finally, there is the question of physical space. Could over five hundred pages of English text really have been derived from the characters inscribed on the Book of Mormon’s gold plates? Once again, comparisons with other ancient documents and scripts provide valuable insights. Hamblin, for example, has compared the 24 plates of Ether with the Iguvine Tablets (3rd–1st centuries BC) discovered in Italy, which are made up of seven large plates, five of which have writing on both sides.27 After several calculations, Hamblin concluded “that it is quite reasonable for the twenty-four plates of Ether to have contained both the book of Ether and Genesis 1–10,” as the Book of Mormon indicates.28

In the 1920s, Janne M. Sjodahl found that the entire text of the Book of Mormon could have fit on only 21 plates (7x8 inches) when written in a compact Hebrew script.29 In 2017, Bruce E. Dale compared the Book of Mormon to a large painting of the Quran, written in Arabic.30 After calculating a number of variables, he concluded that the text of the Book of Mormon likely occupied “about 40 individual plates.”31 While such conclusions are only estimates,32 they suggest that the entire text of the Book of Mormon could indeed have been contained on relatively few metal plates.

The Why

Ancient metal documents were known among scholars33 and probably even a good number of regular folks during Joseph Smith’s day.34 How much Joseph Smith or his associates knew about such discoveries before the Book of Mormon was published, however, is uncertain.

What is clear is that the Book of Mormon and its discussion of metal plates fit in remarkably well with other findings from the ancient world, including many metal documents from the Mediterranean and Near East. Even the book’s unusual length is not all that startling when compared to other rare, lengthy documents from antiquity.35

If the world today possessed the plates upon which the Book of Mormon was written, its material and historical worth, as far as worldly wealth is concerned, would be astounding. Yet, as the prophet Moroni declared, “the plates thereof are of no worth, because of the commandment of the Lord. For he truly saith that no one shall have them to get gain; but the record thereof is of great worth” (Mormon 8:14; emphasis added). While the Book of Mormon shares physical similarities with other ancient metal documents, its powerful testimony of Jesus Christ—the most important measure of its worth—is truly unparalleled.36

Further Reading

William J. Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates in the Ancient Mediterranean,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 37–54.

John A. Tvedtnes, The Book of Mormon and Other Hidden Books: Out of Darkness Unto Light (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000).

John W. Welch, “Doubled, Sealed, Witnessed Documents: From the Ancient World to the Book of Mormon,” in Mormons, Scripture, and the Ancient World: Studies in Honor of John L. Sorenson, ed. Davis Bitton (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 391–444.

H. Curtis Wright, “Ancient Burials of Metal Documents in Stone Boxes,” in By Study and Also By Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley, Volume 2, ed. John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 273–334.

H. Curtis Wright, “Metallic Documents of Antiquity,” BYU Studies Quarterly 10, no. 4 (1970) 457–477.

- 1. See Kirk B. Henrichsen, “How Witnesses Described the ‘Gold Plates’,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10, no. 1 (2001): 16–21, 78.

- 2. See John A. Tvedtnes, The Book of Mormon and Other Hidden Books: Out of Darkness Unto Light (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000), 148.

- 3. This doesn’t mean, however, that the Nephites exclusively kept records on metal plates.

- 4. See H. Curtis Wright and Elisabeth R. Sutton, “Evidence of Ancient Writing on Metal: An Interview with H. Curtis Wright,” Religious Educator 9, no. 3 (2008): 161–168.

- 5. H. Curtis Wright, “Introduction,” in The Book of Mormon and Other Hidden Books: Out of Darkness Unto Light, x.

- 6. See Book of Mormon Central, “Are There Other Ancient Records Like the Book of Mormon? (Mormon 8:16),” KnoWhy 407 (February 3, 2018); Book of Mormon Central, “Are the Accounts of the Golden Plates Believable? (Testimony of Eight Witnesses),” KnoWhy 403 (January 30, 2018); Book of Mormon Central, “What Kind of Ore did Nephi Use to Make the Plates? (1 Nephi 19:1),” KnoWhy 22 (January 29, 2016).

- 7. For various sources which highlight ancient gold documents, see H. Curtis Wright, Modern Presentism and Ancient Metallic Epigraphy (Salt Lake City, UT: Wings of Fire Press, 2006); Tvedtnes, The Book of Mormon and Other Hidden Books; William J. Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates in the Ancient Mediterranean,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 37–54; H. Curtis Wright, “Ancient Burials of Metal Documents in Stone Boxes,” in By Study and Also By Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley, Volume 2, ed. John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 273–334; Paul R. Cheesman, Ancient Writing on Metal Plates: Archaeological Findings Support Mormon Claims (Bountiful, UT: Horizon, 1985); Paul R. Cheesman, “Ancient Writing on Metal Plates,” Ensign, October 1979, online at ChurchofJesusChrist.org; H. Curtis Wright, “Metallic Documents of Antiquity,” BYU Studies Quarterly 10, no. 4 (1970) 457–477; Daniel Johnson, “Metals and Gold Plates in Mesoamerica,” BMAF presentation, 2010, online at bmaf.org

- 8. See Tvedtnes, The Book of Mormon and Other Hidden Books, 75–108.

- 9. See Tvedtnes, The Book of Mormon and Other Hidden Books, 31–58; Wright, “Ancient Burials of Metal Documents in Stone Boxes,” 273–334.

- 10. See John A. Tvedtnes, “Etruscan Gold Book from 600 B.C. Discovered,” Insights 23, no. 167 (2003): 1, 6; “Out of the Dust,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 2 (2006): 65; Warren P. Aston, “The Rings That Bound the Gold Plates Together,” Insights 26, no 3. (2006): 3–4; Jeff Lindsay, “A ‘D’ for Plausibility of the Gold Plates: The Book of Mormon in an Interesting Bind,” online at mormanity.blogspot.com.

- 11. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Would a Book Be Sealed? (2 Nephi 27:10),” KnoWhy 53 (March 14, 2016); John W. Welch, “Doubled, Sealed, Witnessed Documents: From the Ancient World to the Book of Mormon,” in Mormons, Scripture, and the Ancient World: Studies in Honor of John L. Sorenson, ed. Davis Bitton (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 391–444; John W. Welch and Kelsey D. Lambert, “Two Ancient Roman Plates,” BYU Studies 45, no. 2 (2006): 55–76.

- 12. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Would a Book Be Sealed? (2 Nephi 27:10),” KnoWhy 53 (March 14, 2016); Tvedtnes, The Book of Mormon and Other Hidden Books, 59–74; Welch, “Doubled, Sealed, Witnessed Documents,” 391–444; Welch and Lambert, “Two Ancient Roman Plates,” 55–76.

- 13. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Would a Book Be Sealed? (2 Nephi 27:10),” KnoWhy 53 (March 14, 2016); Welch, “Doubled, Sealed, Witnessed Documents,” 391–444.

- 14. Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates,” 53.

- 15. Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates,” 53.

- 16. See Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates,” 39–46, 48.

- 17. For an extensive bibliography of ancient metal records, see Wright, Modern Presentism and Ancient Metallic Epigraphy, 133–346. By their very nature, longer metal documents, such as histories or works of literature, would have been far more costly and time-consuming to create than, say, short monumental inscriptions. It would likely have taken a unique set of circumstances for an ancient ruler or individual to commission or personally inscribe such lengthy records. For discussions of the Book of Mormon as a lengthy metal document, see John A. Tvedtnes and Matthew Roper, “One Small Step,” FARMS Review 15, no. 1 (2003): 160–169; Kevin L. Barney, “A More Responsible Critique,” FARMS Review 15, no. 1 (2003): 104–111.

- 18. See David B. Honey and Michael P. Lyon, “An Inscribed Chinese Gold Plate in Its Context: Glimpses of the Sacred Center,” in The Disciple as Scholar: Essays on Scripture and the Ancient World in Honor of Richard Lloyd Anderson, ed. Stephen D. Ricks, Donald W. Parry, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000), 43. Interestingly, the document was “found in a bronze box within a stone box buried under a five-storied pagoda” (p. 43).

- 19. Caroline Sorensen, “The Metallurgical Plausibility of the Gold Plates,” Summer Seminar on Mormon Culture, Working Papers (2011).

- 20. Honey and Lyon, “An Inscribed Chinese Gold Plate,” 42.

- 21. Honey and Lyon, “An Inscribed Chinese Gold Plate,” 42.

- 22. See Wright, “Metallic Documents of Antiquity,” 461.

- 23. See Wright, “Metallic Documents of Antiquity,” 461.

- 24. See Hans Gustav Güterbock, ed. “The Deeds of Suppiluliuma as Told by His Son, Mursili II,” Journal of Cunieform Studies 10, no. 2 (1956): 41–68, 75–98, 107–130. The implication that this record was anciently engraved onto bronze comes from the text itself. One of the colophons in fragment 28 reads “Not yet made into a bronze tablet.”

- 25. See Wright, “Metallic Documents of Antiquity,” 461; Cheesman, “Ancient Writing on Metal Plates,” online at ChurchofJesusChrist.org; Tvedtnes, The Book of Mormon and Other Hidden Books, 112. It should also be noted that a blessing from the book of Deuteronomy was discovered on rolled up sheets of silver. While quite short in length, the Hebrew-inscribed scrolls date to the 7th century BC, qualifying as the oldest fragments of biblical text ever discovered. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Jesus Allude to the Priestly Blessing in Numbers 6? (3 Nephi 19:25),” KnoWhy 212 (October 19, 2016); Dana M. Pike, “Israelite Inscriptions from the Time of Lehi,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, ed. John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely, and Jo Ann H. Seely (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2004), 213–215; William J. Adams Jr., “Lehi’s Jerusalem and Writing on Silver Plates,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 23–26; “Research and Perspectives: Scriptures on 2,600-Year-Old Silver Scrolls Found in Jerusalem,” Ensign, June 1987, online at ChurchofJesusChrist.org.

- 26. Some might argue that the Book of Mormon’s length alone makes it unlikely to be a product of an ancient society that inherited the Hebrew literary tradition. However, most lengthy ancient metal documents are unique for their time and place. That being the case, there is no logical reason to rule out the possibility that a lengthy metal document could have been produced in Israel or by Israelites displaced from their homeland.

- 27. See Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates,” 51–52.

- 28. Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates,” 52.

- 29. See Janne M. Sjodahl, “The Book of Mormon Plates,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10, no. 1 (2001): 22–24, 79. It should be noted that Henry Miller, the individual who wrote out the Hebrew script by hand for Sjodahl’s experiment, suggested that even if he had used “much larger characters” the entire text of the Book of Mormon could have fit on 48 plates (p. 23). In 2001, John Gee confirmed that the miniscule Hebrew letters used in Sjodahl’s experiment are, on average, about equivalent in size to a sampling of ancient Hebrew inscriptions. Gee recognized that the Hebrew script used in Sjodahl’s experiment was not the written Hebrew used in Lehi’s day, but found that to be a “minor issue.” John Gee, “Epigraphic Considerations on Janne Sjodahl’s Experiment with Nephite Writing,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10, no. 1 (2001): 25. This is, at least in part, due to the fact that most, if not all, of the Book of Mormon was written in a “reformed Egyptian” script that, by its very nature, was more compact than the Hebrew script preserved among the Nephites.

- 30. See Bruce E. Dale, “How Big A Book? Estimating the Total Surface Area of the Book of Mormon Plates,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 25 (2017): 261–268.

- 31. Dale, “How Big A Book?” 268.

- 32. They are estimates because the actual size and literary compactness of the script(s) used on the plates of the Book of Mormon are unknown, nor can readers be certain about the specific dimensions of the plates themselves.

- 33. See William J. Hamblin, “An Apologist for the Critics: Brent Lee Metcalfe’s Assumptions and Methodologies,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 6, no. 1 (1994): 462–470.

- 34. See Michael G. Reed, “The Notion of Metal Records in Joseph Smith’s Day,” Summer Seminar on Mormon Culture, Working Papers (2011).

- 35. The Book of Mormon’s prophetic authors wrote on metal because they were concerned about true doctrines and religious history being passed on to future generations (see, for example, 1 Nephi 4:15–17; 1 Nephi 5:19; 1 Nephi 9:2–5; 2 Nephi 27:9; Enos 1:13, 16–18; Alma 37:8; Mormon 8:23; Moroni 10:27). Thus, short metal documents typically used for monuments, treaties, royal decrees, or memorials wouldn’t have been sufficient. The spiritual and literary purposes of the Book of Mormon required its writers to utilize larger sets of metal records than are typically known in the ancient world. All that was needed was for Book of Mormon authors to utilize an already known method of record keeping for their unique purposes.

- 36. See Russell M. Nelson, “The Book of Mormon: What Would Your Life Be Like without It?” Ensign, November 2017, online at ChurchofJesusChrist.org.

Continue reading at the original source →