Critics of the Book of Abraham have discussed portions of the textual evidence and considered it in light of their theory that Joseph was dictating the translation. Unfortunately, in my opinion, they generally do not seriously allow for the possibility of an alternate hypothesis: that the scribes were creating a copy of an already existing document. The idea of an existing document is typically dismissed with assertions of "no evidence." But the textual evidence they point to in support of their case needs to be evaluated in light of that alternate hypothesis as well in order to make a reasonable comparison of the merits of the two approaches, rather than hastily dismissing the alternative and declaring victory. Fortunately, now anyone can make that evaluation using the publication of high-resolution images and transcripts of the Book of Abraham documents in the Joseph Smith Papers website and in The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts, edited by Robin Scott Jensen and Brian M. Hauglid (Salt Lake City, UT: Church Historian’s Press, 2018). For this, I'm truly grateful to Hauglid and Jensen and the many others who made this possible (in spite of my differences with the editors' apparent personal opinions on some Book of Abraham issues).

To get started, in the Table of Contents for Volume 4 of The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, we can see links to the three key BOA manuscripts in question. These are:

- Document A: "Book of Abraham Manuscript, circa July–circa November 1835–A [Abraham 1:4–2:6]"

- Document B: "Book of Abraham Manuscript, circa July–circa November 1835–B [Abraham 1:4–2:2]"

- Document C: "Book of Abraham Manuscript, circa July–circa November 1835–C [Abraham 1:1–2:18]"

Textual Evidence, Category One: the Spelling of Unusual Names in the Twin Manuscripts

Below are the proper names in each manuscript, excluding Egypt and Egyptian, Ham, Adam, and Noah. They are shown below in order and grouped by name in order of occurrence and showing corrections (here I draw upon data presented in a previous post).Here are the spellings of names in Manuscript A by Frederick G. Williams:

- Elk=Kener, Elk=Kener, Elk=Keenah, Elk-keenah, Elk Kee-nah, Elk-Keenah, Elkkeenah

- Zibnah, Zibnah, Zibnah

- Mah-mackrah, Mah-Mach-rah, Mah-Mach-rah

- Pharoah, Pharaoh, Pharaoh, pharaoh, Pharaoh, Pharaoh, Pharaoh, Pharaoh, Pharaohs

- Chaldea, Chaldea, Chaldeea, Chaldea, Chaldea, chaldees, chaldees, chaldees

- Chaldeans, Chaldians, Chaldea ["in the Chaldea signifies Egypt" - Chaldean is meant]

- Shag=reel, Shag-reel

- Potipher<s> hill, Potiphers hill

- Olishem

OnitusOnitah [Williams spells it improperly, crosses it out and continues with the correct spelling, while Parrish spells it correctly]- Kah-lee-nos [note that the canonized text has Rahleenos]

- Abram, Abram,

Abraham<Abram>, Abram, Abram, Abram - Ur, Ur, Ur, Ur, Ur

- Cananitess, cannites

- Zep-tah

- Egyptes

- Haran, Haron, Haran, Haran, Haran, Haran, Haran

- Terah

- Sarai, Sarai, sarah

- Nahor

- Milcah

- canaan, canaan

- Lot

Manuscript B by Warren Parrish has these proper names showing corrections, as displayed in the transcript at the Joseph Smith Papers site:

Williams spells names with the kind of variation we would expect for an oral copying process: Mah-mackrah and Mah-Mach-rah, Haran and Haron, Elk=Kener and Elk-keenah, Chaldea and Chaldeea. Chaldeans and Chaldians, etc. But Parrish, a poor speller, outdoes his fellow scribe with remarkably consistent spelling of difficult names. This strongly suggests that Parrish could see a document that was being copied. If Parrish could see the document, could he have been the one that was dictating aloud so that he and his fellow scribe could make copies? It's a possibility that needs to be considered as we examine the next category of textual evidence, the typographical errors and corrections. Thus, we will consider two hypotheses: 1) Joseph Smith was dictating and creating a translation as two scribes simultaneously copied what he spoke, and 2) the two scribes worked were simultaneously copying from an existing manuscript, with Warren Parrish able to see and dictate aloud from the manuscript as he and Frederick Williams then copied what Parrish read aloud. Another hypothesis, that someone was reading to both scribes from an existing manuscript, could also be considered, but may be indistinguishable from Hypothesis 2 in analyzing errors and corrections in Category Two.

strikeouts. In the comments, we consider whether the error is more consistent with Hypothesis 1 (live translation being dictated by Joseph Smith) or Hypothesis 2 (two scribes working together as they copy text from an existing manuscript, possibly with Warren Parrish reading aloud and then both Williams and Parrish writing what has been read).

- Elkkener, Elkken[er][here the edge of the paper is damaged obscuring the final r, but it appears that he wrote the full word, Elkkener], Elkkener, Elkkener, Elkkener, Elkkener

- Zibnah, Zibnah, Zibnah

- mahmachrah, Mahmachrah, Mahmachrah

- Pharoah, Pharao[h], Pharaoh, Pharaoh, Pharoaoh, Pharaoh, Pharaoh, Pharaoh, Pharaoh, Pharaoh, Pharaoh

- Chaldea, Chaldea, Chaldea, Chaldea, Chaldea, Chaldeas

- Chaldeans, Chaldeans, Chaldea ["in the Chaldea signifies Egypt" - Chaldean is meant, same error here as in Manuscript A],

- Shagreel, Shagreel

- Potiphers hill, Potiphers hill

- Olishem

- Onitah

- Kahleenos [The canonized text has "Rahleenos." Since a cursive capital R often looks much like a K, it would be easy to read "Rahleenos" on an existing text as "Kahleenos." Williams also wrote "Kahleenos." Perhaps the original text had Kahleenos, or it may have had "Rahleenos" which Parrish or someone else misread.]

- Abram, Abram, Abram

- ur, Ur, Ur

- canaanites, Canaanites

- Zeptah

- Egyptes

- Haran, Haran

- Terah

- Sarai

- Nahor

- Milcah

Williams spells names with the kind of variation we would expect for an oral copying process: Mah-mackrah and Mah-Mach-rah, Haran and Haron, Elk=Kener and Elk-keenah, Chaldea and Chaldeea. Chaldeans and Chaldians, etc. But Parrish, a poor speller, outdoes his fellow scribe with remarkably consistent spelling of difficult names. This strongly suggests that Parrish could see a document that was being copied. If Parrish could see the document, could he have been the one that was dictating aloud so that he and his fellow scribe could make copies? It's a possibility that needs to be considered as we examine the next category of textual evidence, the typographical errors and corrections. Thus, we will consider two hypotheses: 1) Joseph Smith was dictating and creating a translation as two scribes simultaneously copied what he spoke, and 2) the two scribes worked were simultaneously copying from an existing manuscript, with Warren Parrish able to see and dictate aloud from the manuscript as he and Frederick Williams then copied what Parrish read aloud. Another hypothesis, that someone was reading to both scribes from an existing manuscript, could also be considered, but may be indistinguishable from Hypothesis 2 in analyzing errors and corrections in Category Two.

Textual Evidence, Category Two: Typographical Errors and Corrections in the Common Text of the Twin Manuscripts

Here we consider each of the errors and corrections, in order, for the common text written by by both scribes, namely, Abraham 1:4 to 2:7, the point where Parrish stopped writing. Unless otherwise stated, the errors and corrections shown occur in both manuscripts. Corrections made by only a single scribe (mostly Williams) are not shown. Insertions are put between <brackets>. Deletions are marked as| Errors and Corrections | Comments |

|---|---|

| (1) "sign of the fifth degree of the | A correction made above the line after writing the full designation, apparently when one of the scribes recognized that it should be "first" rather than "second." On an existing document being copied, this designation may not have been written, but could have been a note from the scribes. Of itself, this correction could be consistent with with Hypothesis 1 or 2. |

| (2) "I sought for <mine> | The final sentence here has both "mine appointment" and "the appointment" right after it. When copying by hand from an existing text or reading aloud from an existing text, skipping ahead (or looking back) to a similar phrase and momentarily confusing the two is an easy and common mistake to make. Switching a nearby "the appointment" for the immediate "mine appointment" would be completely understandable, if one were working from an existing text. It's also possible that a reader were not used to "mine" in front of a noun could also subconsciously make it more natural by reading "the" for "mine." In any case, looking at an existing text and copying or reading could readily result in this error, whereas if one had decided to speak of "my appointment" but in old fashioned language, it's unlikely that one would slip and just say "the" instead, when the context of the sentence demands a possessive. This is an error most likely due to working with an existing text. This favors Hypothesis 2. |

| (3) " | How could "appointment unto" become "appointment whereunto" if one is dictating one's own words and ideas? This mistake, however, is very natural when reading from an existing text. The conversion of "unto" into "whereunto" makes sense as a reading error given that "whereunto" was just used in a similar context earlier in Abraham 1:2, assuming that that verse was present on the hypthesized existing manuscript or had been read recently by the reader. This favors Hypothesis 2. |

| (4) Williams: "and that you might have a knowledge of this alter <I will refer you to the representation that is at the commencement of this record>" Parrish: "and that you might have a knowledge of this altar, I will refer you to the representation, | Williams' text looks as if he is cramming the inserted words into the speace between the end of one paragraph and the beginning of the next, as if he has missed these words and later learned of the need to add them after the next paragraph had been started, which begins with, "It was made after, the form of a bedstead...." Parrish, however, continues writing "I will refer you..." smoothly, but has a deletion not found in Williams' text. These facts are difficult to fit into a Hypothesis 1 scenario but could fit a Hypothesis 2 scenario. Parrish may have struggled with confusing markings on the original text, writing a phrase that had been marked for deletion before continuing with the correction, and while so doing failed to read this portion until after he had read the next line associated with a new character. When he read the resolved passage aloud, there was no error for Williams to correct, but he had to cram the passage into the limited space left before the new paragraph already begun. Hypothesis 2 is favored. |

| (5) Parrish: "the daughters of Onitah, one of the | Only Parrish makes the error of writing "regular" instead of "royal." It would seem highly unlikely to hear "royal" and write "regular" instead, but this would be an easy visual mistake to make since the first five letters of a cursive "regular" can look very much like "royal." In a Hypothesis 2 scenario, Parrish may have first written the word "regular" then immediately noted and corrected mistake before reading the sentence properly to Williams, or may have dictated the text correctly, and then visually looked back to review what he had just read, leading to the visual copying error. In any case, this error favors Hypothesis 2. |

| (6) Williams: <That you may have an understanding of their gods I have given you the fashion of them in the figures at the begining which manner of figures is called by the Chaldians, Kah-lee-nos.—>" | The editors of JSPRT Vol. 4 plausibly classify this passage as an insertion because it appears to have been squeezed into the top of a page (see foonote 64 on p. 239). This text is inline in Parrish's manuscript. For Hypothesis 1, this might mean that Williams didn't pay attention and missed a section that he later had to fill in. Under Hypothesis 2, if Parrish had already been distracted and failed to read a phrase out loud just moments before, it might have happened again here, especially since the text is again making a possibly confusing reference to a previous figure. Both could be plausible. However, since significant single-scribe errors of this kind tend to be those of Williams, that is consistent with a Hypothesis 1 scenario where Parrish is able to see the manuscript and thus does not miss significant passages that Williams succeeds in recording. Also of note are the details of Williams' initial spelling of Keh-lee-nos, not shown in the transcript on the website but given on p. 197 of the book, where we see that he initially spelled the name with "Ca" instead of "Ka." Indeed, it appears he wrote "Cale" first, then, perhaps after asking how to spell it, reworked the letters to become "Kah-" followed by "lee-nos," again consistent with Williams' writing names with the uncertainty of oral dictation, while Parrish, in contract, spells them with great regularity (see point 7 below). |

| (7) Parrish: "which manner of figures <is> | Of note here is Parrish's error of writing "Egyptians" instead of Chaldeans initially, which he strikes out immediately and then continues inline with "Chaldeans." This appears to be a mental error in logically expecting "Egyptians." This could happen under wither scenario. Since Williams wrote it correctly, that must have been what was dictated. Under Hypothesis 2, Williams could have dictated it before or after making the written mistake. Also of note, Parrish here spells "Kahleenos" without stumbling, and spells Chaldeans correctly, while Williams erred (at least initially) on both (see point 6 above), further strengthening the evidence under Category One for Hypothesis 2. |

| (8) "because | This error is easily compatible with Hypothesis 1, wherein Joseph could have adjusted a phrase on the fly, revising "their hearts are turned" to "they have turned their hearts." However, there is an interesting twist to this example that we learn from John Gee in his Introduction to the Book of Abraham, p. 31. He explains that these two phrases are equivalent in Egyptian, and could be translated either way, a possible hint at the Egyptian language origins of this change. That could again be consistent with Hypothesis 1. It could also occur under Hypothesis 2 if the original manuscript Parrish was seeing had the initial phrase only lightly stricken out or with a penciled in correction that caused initial confusion about the editorial intent. However, for this issue, Hypothesis 1 is favored. |

| (9) Williams: "and to distroy him, who hath lifted up his hand against thee Abra | Here Williams makes and quickly corrects two errors that Parrish does not make. He changes "Abraham" to the dictated "Abram," an easy mistake to make when taking diction, and then, having just written "distroy" in this phrase, writes it again in "distroy thy" for the similar meaning of "take away thy life." This could happen under both Hypothesis 1 and 2, but since Parrish does not make the mistake, consistent with being able to see the text that he dictates and thus able to have relatively fewer errors incuding fewer errors with names. Hypothesis 2 thus may be slightly favored. |

| (10) Williams: "the Lord broke down the alter of Elk-Keenah and of the gods of the land, and utterly distroyed them Parrish: "the Lord broke down the altar of Elkkener, and of the gods of the land, and utterly destroyed | Williams repeats the phrase "gods of the land" after "utterly distroyed them." At that point, "gods" is right above the space where he continues to write, and its appearance may have triggered the repeated phrase. Parrish does not make this error, but does write "these" and then corrects it. Under Hypothesis 2, it is possible that Parrish misread this passage as "them gods of the land," visually jumping back to the phrase "gods of the land" as he read, then mentally correcting the grammar to "these" as he wrote, after which then realized he had misread the phrase in time to have Williams strike "gods of the land." The errors of the two scribes here could be random individual errors consistent with either Hypothesis 1 or 2, but Hypothesis 2 may explain a non-random relationship between them, possibly giving Hypothesis 2 the edge here for explanatory power. Note also the presence of additional punctuation in Parrish's text (commas) that is lacking in Williams', an issue consistent with Hypothesis 2 to be discussed under Category 3 below. |

| (11) "And thus from Ham sprang | Both scribes write "the" and then change it to "that" by writing "at" over "e," a correction that could have been done immediately or later. This could be consistent with either hypothesus. In the following sentence, both scribes insert "first" above the written line. This could happen under Hypothesis 1 if Joseph, after dictating a sentence about the origins of Egypt, felt he needed to add first afterwards. But the thought being expressed seems somewhat off without the "first," possibly suggesting that it's more likely to be the kind of mistake that was made by a reader who skipped a word rather than a speaker who didn't think of the word until later. This could work with either hypothesis, but Hypothesis 2 may be slightly favored. |

| (12) "in the days of the first patriarchal reign, even in the reign of Adam; and also Noah his father, | Both scribes write "for in his days," indicating that the speaker spoke those words. In Williams' text, there is a period after "for in his days" followed by a capitalized "Who" that is then changed to a lower case "who." This is relatively hard to fit under Hypothesis 1, but may fit under Hypothesis 2, for the similar phrase "in the days" leads this passage and could have influenced the reader after seeing those words above to add a related phrase. Upon noticing and reading "who blessed him," the incongruity would have been noted and the error detected. Williams may have heard "who blessed him" as a new sentence since it didn't fit as a continuation suitable for "for in his days" and thus began a new sentence. When Parrish explained the error, Williams then changed "Who" to "who." Parrish, having seen and written the correct case for "who," did not have to make such a change. This correction seems to favor Hypothesis 2. The other correction, changing "of" to "with," is also consistent with a scribal error made by seeing another nearby word. Note that "of" occurs right before ("of the earth") and after ("of wisdom") the intended "with," making this an easy copying mistake and but an unlikely error for Joseph expressing thoughts in his own words. In both cases, Hypothesis 2 is favored. |

The scribal errors and corrections are said to provide compelling evidence that Joseph Smith was dictating and creating live but utterly ridiculous "translation," giving us a window into Joseph's "translation" process. But in nearly every instance of significant scribal errors and corrections in the commonly treated text, when the alternative possibility of copying from an existing text is considered, that alternate possibility, our Hypothesis 2, appears to have more explanatory power. Hypothesis 1 is favored in one case, and the two hypotheses may be equally suitable in a couple of cases, but in a majority of the cases there are plausible reasons for favoring Hypothesis 2. On the whole, the evidence in both Category Two and Category One favors a preexisting manuscript that was being copied, with dictation possibly by Warren Parrish to assist his fellow scribe as both made copies for some reason. Claims that there is "no evidence" for an existing manuscript being used by the scribes fall flat. That's an assertion, not a scholarly conclusion based on detailed textual analysis. We still have question marks about what the scribes are doing and what the purpose of the characters in the margins is. They see a relationship, of course, but if they are copying from an existing manuscript, these "smoking gun" manuscripts are not giving us a window into Joseph Smith's live translation.

Next up will be Category Three of our textual evidence dealing with format and punctuation, a lesser but still noteworthy issue, and then Category Four, analyzing the text Williams produced after Parrish left or stopped writing. Finally, we will look at Book of Abraham Manuscript C and consider what it tells us or doesn't tell us about the twin manuscripts A and B and other Book of Abraham issues.

Update, July 7, 2019

Textual Evidence, Category Three: Format and Punctuation

While critics insist that there's absolutely no evidence for the existence of a Book of Abraham that could have been used by the scribes when they created Book of Abraham Manuscripts A and B (the twin manuscripts), this is an argument of polemics and not a scholarly evaluation. Whether one finds it compelling or not, there certainly is evidence to consider when the blinders come off. Vol. 5 of the Joseph Smith Papers, a volume that at least one of the "no evidence" critics has cited by way of illustrating the groundless assertions made by apologists regarding the existence of an earlier manuscript, does more than just assert that an earlier document existed, but points to meaningful evidence: "Documents dictated directly by JS [Joseph Smith] typically had few paragraph breaks, punctuation marks, or contemporaneous alterations to the text. All the extant copies, including the featured text, have regular paragraphing and punctuation included at the time of transcription, as well as several cancellations and insertions." Rogers et al., The Joseph Smith Papers, Documents, Volume 5, footnote 323, pp. 74–75. In other words, the formatting and punctiation of the twin manuscripts suggest they were not created the same way as typical documents from Joseph's live dictation.An example of Joseph's dictation without punctuation until it was added later is seen in the Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon and in typical dictation for the Doctrine and Covenants, such as the vision recorded in our current Section 76. You can see how the scribes wrote that on the Joseph Smith Papers website.

The critics can argue that paragraphs in the twin manuscripts were necessitated by the placement of Egyptian characters. That's a reasonable argument. However, the existence of punctuation and marking for revisions in the text may favor the theory that the scribes were working with an existing document. In Parrish's Manuscript B, there are 130 commas, 30 periods, 5 semicolons, and 1 colon. In Williams' Manuscript A, there are only 46 commas, 16 periods, 7 colons and 8 semicolons for the text up to Abraham 2:2, where Parrish ends. Williams has much less punctuation that Parrish. This makes sense if Parrish is looking at a document that has punctuation and is trying to follow that, whereas Williams is hearing an oral reading and trying to occasionally add punctuation where it seems needed.

If, however, the scribes are copying an existing manuscript, then the real question is whether that manuscript was based on original translation from Joseph and whether it had characters on it at the time of dictation. The document being copied may have had characters added later by a scribe, or may have had notes about where one might wish to insert characters, or may have said nothing about characters. It's unclear from the manuscripts when the "Egyptian" characters were placed in the margins: all at once, one or two at a time after adding the English text for the previous characters, or some other system. Parrish stops Manuscript B after he has written a character in the margin with no English, so he may have been writing characters before the English. In Manuscript C, there are two characters that Parrish scraped off to reposition them to be better aligned with the text (see the image below from page 7 of Manuscript C), suggesting that the position of the characters was importnat to him, although this was a case where Parrish was copying text and characters he had previously written in Manuscript B, so it doesn't tell us much about what Parrish was thinking and seeking to do when he prepared Manuscript B. For Manuscript C, it's possible that two adjacent characters were just sloppily placed and then later adjusted. In any case, understanding that two characters were scraped off and repositioned in Manuscript C tells us nothing new about Manuscripts A and B, even if they did represent live dictation from Joseph Smith. But it's reasonable to assume that the placement of the characters by the scribes was important to them and reflected some kind of association with the specific blocks of text they were next to. But if the text was copied from an existing manuscript, the twin manuscripts don't necessarily tell us much about how Joseph did the translation that generated the missing existing document.

Textual Evidence, Category Four: Williams' Dittography After Parrish Stopped Writing

Williams' Manuscript A at page 4 ends with a strange duplicate section where a lengthy section, Abraham 2:3 to 2:5, is repeated. This phenomenon, "dittography," is characteristic of copying a text and mistakenly looking back at a previously copied phrase or region as one continues. It's a common scribal error. It would be highly unlikely, even virtually impossible, to redictate this much text word for word in a purely oral process, especially if one were in the process of making it up on the fly. But this kind of error could easily occur if one were copying a document. But yes, it could also occur in an oral process -- if the one giving dictation were reading from an existing manuscript, though that seems less likely than simply copying from a text one can see.If Manuscript A and B reflect dictation and an oral process, it is natural to assume that Joseph or someone else was dictating to his scribes. Joseph did often dictate to scribes (or rather, to one scribe at a time, not two at once as far as I know) when receiving revelation and performing "translation" by whatever means. But we should also consider another possibility. It is not necessary that Joseph or anyone else was reading out loud to the two scribes. One of the two scribes could have done that, as noted above. Warren Parrish, based on spelling issues, appears to be a likely candidate for the one who was dictating.

With a document in front of him, Parrish could have been reading aloud for the benefit of Williams, alternately reading a few words at a time and copying what he just spoke. Whatever was going on, it didn't last, for Parrish, the scribe working on Manuscript B, stopped early after writing "who was the daughter of Haran" from Abraham 2:2. However, Frederick G. Williams kept on writing on Manuscript A. It was at this point where something changed, as is visible in the image above (Manuscript A, p. 4), perhaps due to Parrish's departure and a change or interruption associated with that. Perhaps the key change was that Williams could now just copy text directly without hearing the spoken text and without thinking about what he had just heard. It was at this point where Williams writes Abraham 2:3-5, and then creates a massive dittography blunder by copying those three verses again, word for word (with a couple of minor typos and "bro son" instead of "brother's son"). The change also includes writing all the way to the left margin of the page instead of respecting the column holding occasional Egyptian. Williams may have recognized or assumed that there were no new characters to write for this added text or may have wanted to cram in the rest of his text onto this page, and so he chose to write text in the left margin, no longer leaving that space open for characters.

Dan Vogel has offered an interesting theory for this dittography in his video at youtube.com/watch?v=AtJT_xjIgdM. He suggests that when the twin manuscripts were produced, Williams (for an unknown reason) wrote an extra paragraph of dictation that Parrish did not write (our current Abraham 2:3-5). Parrish later copied that into Manuscript C and then in late November 1835 added new dictation from Joseph Smith for Abraham 2:6-18. Williams later wanted to add some of the new material to his manuscript. Since his manuscript originally ended with the word "Haran" in "Therefore he continued in Haran," he searched for "Haran" in Parrish's document (a word that occurs multiple times) and found the wrong place, Abraham 2:2, which ends with "Who was the daughter of Haran." Seeing "Haran" there, he began copying our current Abraham 2:3 and continued copying a full paragraph of material he had already written, not noticing the duplication.

Vogel's theory has the benefit of recognizing that a dittography of this nature likely does require that a scribe was copying from an existing manuscript. Here the existing manuscript was Parrish's new Manuscript C. Vogel also speculates that since Williams was copying from an existing text instead of acting as a scribe from Joseph's live dictation, he now saw no need to copy the characters in the margin of Parrish's document, which otherwise would have resulted in the same character being copied twice in the margin. That reasoning is unclear, in my opinion, but nothing is terribly clear when it comes to guessing what the scribes were doing and why with the KEP.

On the other hand, the nature of the ink mix being used, the density of the ink and the details of spacing, slant, etc. in the handwriting of Williams all seem identical before and after the supposed break of multiple days between the first time and second time Abraham 2:3-5 were written. Visually, it appears that Williams just kept writing in the same way with the same ink and pen. That could happen naturally even with a lengthy break and a new mix of ink, I suppose, but there doesn't seem to be the kind of break one might expect.

But something has changed, as evidenced by Williams' change in margins. The change may be related to a change in environment or a lack of input about additional characters to add, or coming to the end of a page and seeking to fit the upcoming material onto his page. We don't know what Williams was considering when he disregarded the previous left margin, but clearly something significant had changed. That change may have been related to Parrish's departure and the need to use the existing manuscript on his own.

Vogel admits that his theory is complex and relies on some bad luck and sloppiness in picking the wrong Haran, versus the more "straightforward" but still sloppy error of a "straightforward" dittography based on looking at the wrong part of document during a single copying session. Given the lack of visual evidence of an interruption in time in the middle of the dittography, it seems that the simpler, more straightforward explanation would be a dittography in one setting while visually copying an existing manuscript. There are questions for either theory, though. While either Hypothesis 1 or 2 may be tenable, I think Hypothesis 2 is slightly favored for its simplicity and for the lack of visually discernible evidence of a lengthy break of multiple days before the dittography occurred.

What We Learn from Manuscript C

Manuscript C begins with Abraham 1:1-3 written by W.W. Phelps in his characteristic heavy black writing.The November 1835 date generally offered by critics for the creation of Abraham 1:1-3 is strongly contradicted by Oliver Cowdery's usage of that passage in a recorded blessing he gave in the summer or fall of 1835, apparently penned in September 1835:

But before baptism, our souls were drawn out in mighty prayer to know how we might obtain the blessings of baptism and of the Holy Spirit, according to the order of God, and we diligently saught for the right of the fathers, and the authority of the holy priesthood, and the power to admin[ister] in the same: for we desired to be followers of righteousness and the possessors of greater knowledge, even the knowledge of the mysteries of the kingdom of God. Therefore, we repaired to the woods, even as our father Joseph said we should, that is to the bush, and called upon the name of the Lord, and he answered us out of the heavens, and while we were in the heavenly vision the angel came down and bestowed upon us this priesthood; and then, as I have said, we repaired to the water and were baptized. After this we received the high and holy priesthood….

[Oliver Cowdery, Patriarchal Blessings, 1:8–9, cited in “Priesthood Restoration,” Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/site/priesthood-restoration. The JSPP site states that this was “probably recorded summer/fall 1835,” while Christopher Smith states it was Sept. 1835. See Christopher C. Smith, “The Dependence of Abraham 1:1—3 on the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar,” The John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 29 (2009): 38–54, citation at 52; https://www.academia.edu/2357346/The_Dependence_of_Abraham_1_1-3_on_the_Egyptian_Alphabet_and_Grammar. The flaws in Smith's analysis of Abraham 1:1-3 will be discussed in more detail in a future report.]

Oliver is using language from Abraham 1:2, where Abraham “sought for the blessings of the fathers, and the right whereunto I should be ordained to administer the same … desiring also to be … a greater follower of righteousness, and to possess a greater knowledge, and … I became a rightful heir, a High Priest, holding the right belonging to the fathers.” Christopher Smith recognizes that Cowdery is drawing upon the Book of Abraham, not scattered phrases from the GAEL, and thus properly concludes that Abraham 1:1–3 must have been completed before Sept. 1835. However, he improperly concludes that the GAEL therefore must have been completed before Sept. 1835, maintaining the assumption that the GAEL must have come first. It’s much more reasonable to recognize that it came later and was drawing upon the translation for whatever its purpose was.

The important thing for now, though, is that Abraham 1:1-3 was available for Oliver to cite well before November 1835, greatly strengthening the case that translation of at least part of the Book of Abraham had occurred that summer and that an existing document was available. Why Parrish and Williams did not choose to copy that portion or why they did not have that portion before them when they copied their manuscripts is unclear. But Abraham 1:1-3 was in existence already at that time.

Vogel argues that in the new material Parrish added, the mistake of writing "the" instead of "thee" is consistent with a hearing error from live dictation. But he overlooks the important evidence from Parrish's copying of Abraham 2:3 from his own prior manuscript where Parrish now writes "Abram, get the out of thy country" when "thee" is meant. (The transcript from the JSP is "Abram, get the[e] out of thy country" where [e] indicates an editorial correction to show what was obviously meant.) So this establishes that writing "the" for "thee" is exactly the kind of visual copying error that Parrish can make. It seems highly unlikely that a scribe, upon hearing "thee" in a context where "thee" or "you" is clearly needed, would think that "the" had been dictated and write it that way. It's a visual copying error.

Here is the transcript from the Joseph Smith Papers website for the portion of Manuscript C that contains new material not found in Manuscript A or B, material that Vogel and others say represent live dictation from Joseph Smith of newly "translated" material:

But I Abram and Lot my brothers son, prayed unto the Lord, and the Lord appeared unto me, and said unto me, arise and take Lot with thee, for I have purposed to take thee away out of Haran, and to make of the[e] <a> minister to bear my nameA couple of these could make sense as changes made by Joseph during live dictation, especially changing "eternal memorial" to "everlasting possession." On the other hand, that could be an example of a "false memory" where the scrine reads a phrase, understands the meaning, and accidentally writes something similar in their own words, a mistake which I frequently catch myself making. Another good candidate for a live dictation scenario, in my opinion, is deleting "unto a people which I will give" and then writing "in a Strange land which I will give". But this could still be an error from visual copying since both phrases have "which I will give." Parrish may seen "to bear my name ... which I will give" and mentally reconstructed it as bearing his name to a people "which I will give." That's a fairly big mistake, though, but not an impossible one.unto a people which I will givein a Strange land which I will give unto thy seed after thee, for aneternal memorialeverlasting possession <when>ifthey hearken to my voice.

For I am the Lord thy God, I dwell in heaven, the earth is my footstool. I stretch my hand over the sea, and it obeys my voice I cause the wind and the fire to be my chariot, I say to the mountains depart hence and behold they are taken away by a whirlwind in an instant suddenly, my name is Jehovah, and I knowthe beginningthe end from the beginning, therefore my hand shall be over thee, and I will make of thee, a great nation and I will bless thee, above measure, and make thy name great among all nations.

And thou shalt be a blessing, unto thy seed after thee, that in their hands they shall bear this ministry and priesthood unto all nations, and I will bless them, through thy name, for as many as receive this gospel,inShall be called after thy name, and shall be accounted thy seed, and shall rise up and bless thee, as unto their father, and I will bless them that bless thee, and curse them that curse thee, and in theeand in(that is in thy priesthood.) and in thy seed, (that is thy pristhood) for I give unto the[e] a promise that this right shall continue in thee, and in thy seed after thee, (that is to say thy literal seed, or the seed of thy body,) shall all the families of the earth be blessed, even with the blessings of the gospel, which are the blessings of salvation, even of life eternal.

Now after the Lord had withdrew from speaking to me, and withdrew his face from me, I said in my heart thy servant has sought thee, earnnestly, now I have found thee, thou didst send thine angel to delivr me, from the gods of Elkkener, and I will do well to hearken, unto thy voice, therefore let thy servant arise up and depart in peace so I Abram departed, as the Lord had said unto me, and Lot with me, and I Abram was sixty and two years old, when I departed out of Haran.

And I took Sarai, whom I took towife in Ur of Chaldeeawife when I was in Ur, in Chaldeea, and Lot my brothers Son, and all our substance, that we had gathered, and the souls that we had won in Haran, and came forth in the way to the land of Canaan, and dwelt in tents, as we came on our way, therefore eternity was our covering, and our rock, and our salvation, as we journeyed, from Haran, by the way ofjershJurshon, to come to the land of canaan.

Now I Abram, built an altar unto the Lord, in the land of Jurshon and made an offiring unto the Lord and prayed that the famine, might be turned away from my fathers house, that they might not perish; and then we passed from jurshon through the land unto the place of Sichem, it was situated in the plains of Moreh, and we had already, come into theland<land of the> <borders> of the Canaanites, and I offered sacrifice there, in the plains of Moreh, and called on the Lord devoutly because we<[we]> had already come into the land of this Idolitrous nation.

Most of the other errors involve words that occur nearby in the text that could have resulted in the scribal error by jumping ahead or behind to the matching word. Thus, "in thee (that is in thy priesthood) and in thy seed, (that is thy pristhood)" could have resulted in accidentally inserting the later "and in" before the first parenthetical remark by visual copying. Likewise, "into the borders of the land of the Canaanites" could have been written as "into the land of the Canaanites" and "took to wife when I was in Ur, in Chaldeea" could easily have been copied visually as "took to wife in Ur of Chaldeea" (a haplography). Several of the corrections, including "the" for "thee", are not likely to have been resulted from oral dictation, while most make good sense as visual copying errors, with the most serious weakness being the insertion of "unto a people" before the "which I will give." But such an error is still within the scope of the possible mental errors people make when copying text.

Based on textual analysis, there is not a slam-dunk case that live dictation with the creation of new material has occurred in Manuscript, either for the allegedly new material from W.W. Phelps at the beginning, or in the allegedly new material being written at the end of the document by Warren Parrish. Manuscript C does not undermine the existence of a prior document that contained the translation of the Book of Abraham for at least Abraham 1:1 to Abraham 2:18.

Update, July 18, 2019 & July 21, 2019: One further area of evidence is from the material from Abraham 2:3-5 that Williams has in Manuscript A before the dittography. Williams makes the same scribal error that Parrish makes twice in Manuscript C, writing "the" for "thee" -- a mistake that makes the most sense as a mistake of visual copying rather than of hearing. But there are some other interesting corrections suggestive of visual copying that are shown in detail in the book on the Book of Abraham documents, Volume 4 of The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, p. 201. There we see that "land" in "unto a land" was initially written with "t" as the leading letter, and then written over or converted to "l" but with the cross stroke of "t" still visible. Confusing a "t" for an "l" is unlikely when taking verbal dictation but not hard to imagine when copying visually. Later, the "dwelt" in "tarried in Haran and dwelt there, as there" was initially written with an "s" instead of a "d", a mistake that is very hard to imagine when taking dictation. However, if Williams were visually copying, note that "dwelt there" is immediately followed by "as there", a phrase that connects an "s" sound before "there." I can imagine that the "s" before the following "there" could have been spotted in visual copying, looking at the wrong "there", resulting in momentary confusion. It looks like the error was immediately caught and the "s" was turned back into a "d" before finishing the word "dwelt." I'm not sure how the mistake happened, of course, but it's not a likely hearing mistake. It points to copying from an existing document.

Adding this to the previously discussed material prior to Abraham 2:3-5, the common material written by Parrish and Williams, we see a strong trend that undermines theories based on Williams and Parrish taking live dictation of newly created material from Joseph Smith. There most likely was an existing manuscript that was being used to make two copies of a portion of the text for some purpose.

[July 21 update begins here.]

Further, in considering the repeated material in Manuscript C, the dittography of Abraham 2:3-5, while everyone should agree that this repeated text has been copied visually, there is a question as to what was being copied. The uniformity in writing suggests to me that this was copied in a single sitting and thus would be from the same manuscript from which both Parrish and Williams had been making a copy. Dan Vogel, on the other hand, argues that the dittography was made later when Williams sought to add new material that Joseph allegedly had dictated to Warren Parrish in Manuscript C, but then started at the wrong spot, copying text he already had. Can we see evidence that the repeated text closely follows Manuscript C?

In Manuscript C, Parrish writes, "Now the Lord had said unto me Abram, get the[e] out of thy country, and from thy Kindred, and from thy fathers house." He has made the same mistake that Williams made in the first writing of Abraham 2:3-5, leaving the second "e" off of "thee." But the second time, when supposedly copying the Parrish text of Manuscript C, Williams gets it right. But he may have just been paying attention and recognized it had to be "thee."

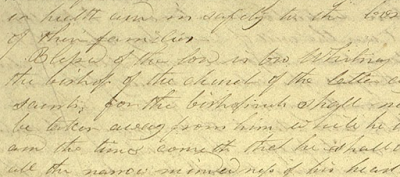

More interesting is what happens at the end of this sentence. Parrish has "house" and it's clear, with an unmistakable "s". In the image below from Manuscript C, you can see "house" in the lower right, and also Parrish's errant "the" at the top and a normal "thee" at the bottom, for comparison. Notice how clear "house" is. There is no way this should be mistaken for "home," which is what Williams has written. Changing "home" to "house" can be a memory error, reprocessing a word heard orally for a similar word when writing it down moments later, but Williams has "home" both time in writing Abraham 2:3. It seems unlikely that he is copying Parrish's version. (Another hat tip to Joe Peaceman on this point.)

|

| Portion of Parrish's Manuscript C showing his error of "the" for "thee" and the use of "house," not "home." |

In the scenario where a reader other than Parrish is reading to the two meen, the reader may have left when Parrish did, leading to Williams making a visual copy with the huge dittography, or the reader may have kept reading for the first round of Abraham 2:3-5 and then left or just gave the manuscript to Williams to copy for himself, at which point he might have made the kind of mistake that Dan Vogel proposes, looking for the word "Haran" as the marker for where he left off, but seeing the wrong "Haran" and thus starting at the wrong place, resulting in the dittography. In such a case, Willilams like the reader would have also read "home" instead of "house." Of course, the document that Parrish and Williams were copying may have had "home," which became "house" through a scribal error or editorial change later on.

In any case, the textual evidence in several ways challenges Vogel's proposal that the dittography was a later effort of Williams to copy from Manuscript C. There is no change in style or ink flow, a failure to repeat Parrish's mistake of "the" for "thee" and apparent failure to copy Parrish's "house." None of these are absolute proofs and each can be debated, but cumulatively they create prima facie evidence that Williams is not copying a later manuscript from Parrish.

|

| F.G.W.'s second occurrence of "fathers home" from Abraham 2:3. |

| |

| F.G.W.'s second occurrence of "fathers home" from Abraham 2:3. |

|

| Example of "se" in F.G.W.'s "these things" from the same page as the dittography. |

|

| F.G.W.'s confusing but still discernible "caused" in "God caused" from the same page as the dittography. |

Also consider Williams' "women" from page 1 of Manuscript A. You can see the "ome" looks very similar to the letters in his second "home," strengthening the case that it is indeed "home" and not "house."

Update, July 19, 2019:

In Book of Abraham Manuscript A, one of the factors suggesting that the dittography from Frederick G. Williams occurred in a single session (contrary to the creative theory of Dan Vogel about later copying the repeat section from Manuscript C) is the strong uniformity of appearance of the first and second occurrences of Abraham 2:3-5. The ink itself, the ink flow, the slant and general style of the two sections appear to be remarkably uniform, as if it were done in a single sitting. Or perhaps he always wrote just like that?

To get a feel for the variability that may occur in writing from Williams, consider these samples of other documents in the handwriting of Williams made at other times, found by searching for "handwriting of Frederick G." on the Joseph Smith Papers Project (JSPP) website, JosephSmithPapers.org.

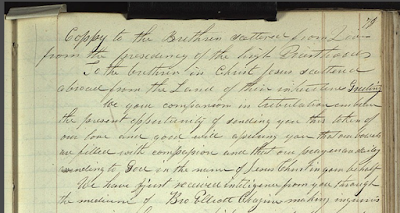

First consider this letter from around the same time as Williams' work with the Kirtland Egyptian Papers: "Letter from Harvey Whitlock, 28 September 1835."

Here Williams is obviously making a copy of an existing text. Note the scribal error he makes by jumping ahead to a later portion of the letter and writing "unbosom my feelings." The transcript of this portion has:

...plainness of sentiment with which I wish toWhen he crossed out the erroneous words and continued writing, the ink or the ink flow seems to change, resulting in somewhat darker text. There may have been a break or pause before this point, or simply a refreshing of his ink source, though it's hard to know. In any case, it illustrates that his writing can vary within a single document and how easy it is to make mistakes when visually copying a document.unbosom my feelingswrite. For know assuredly sir to you I wish to unbosom my feelings, and unravil the secrets of my heart: as before the omnicient Judge of all the earth.

Here is a document from October 7, 1835, listed in the JSPP website as "Blessing to Newel K. Whitney, 7 October 1835," where we see a relatively high slant angle:

Below is the opening portion of a document in the JSPP website listed as "Letter to the Church in Clay County, Missouri, 22 January 1834." Here we see relatively dark ink and a high slant angle:

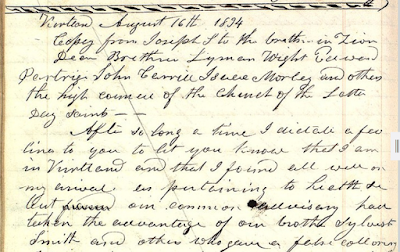

Another example of very dark ink is seen in his "Letter to Lyman Wight and Others, 16 August 1834":

Here is a document listed in the JSPP website as "Revelation, 5 January 1833":

There is plenty of variability in Williams' writing. That his Book of Abraham Manuscript A is so uniform across the large dittography is significant evidence that it occurred in a single setting, right after Parrish left, as if he were no longer taking dictation (from Parrish or anyone else) and was no copying from a manuscript visually. While I think it's most likely that Parrish was the one giving dictation, it's possible someone else was reading and left when Parrish did or after reading the first portion of Abraham 2:3-5. Williams was certainly copying from an existing text when he repeated Abraham 2:3-5, and it most likely was the same text from which the earlier portions of his document came from.

This post is part of a recent series on the Book of Abraham, inspired by a frustrating presentation from the Maxwell Institute. Here are the related posts:

- "Friendly Fire from BYU: Opening Old Book of Abraham Wounds Without the First Aid," March 14, 2019

- "My Uninspired "Translation" of the Missing Scroll/Script from the Hauglid-Jensen Presentation," March 19, 2019

- "Do the Kirtland Egyptian Papers Prove the Book of Abraham Was Translated from a Handful of Characters? See for Yourself!," April 7, 2019

- "Puzzling Content in the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar," April 14, 2019

- "The Smoking Gun for Joseph's Translation of the Book of Abraham, or Copied Manuscripts from an Existing Translation?," April 14, 2019

- "My Hypothesis Overturned: What Typos May Tell Us About the Book of Abraham," April 16, 2019

- "The Pure Language Project," April 18, 2019

- "Did Joseph's Scribes Think He Translated Paragraphs of Text from a Single Egyptian Character? A View from W.W. Phelps," April 20, 2019

- "Wrong Again, In Part! How I Misunderstood the Plainly Visible Evidence on the W.W. Phelps Letter with Egyptian 'Translation'," April 22, 2019

- "Joseph Smith and Champollion: Could He Have Known of the Phonetic Nature of Egyptian Before He Began Translating the Book of Abraham?," April 27, 2019

- "Digging into the Phelps 'Translation' of Egyptian: Textual Evidence That Phelps Recognized That Three Lines of Egyptian Yielded About Four Lines of English," April 29, 2019

- "Two Important, Even Troubling, Clues About Dating from W.W. Phelps' Notebook with Egyptian "Translation"," April 29, 2019

- "Moses Stuart or Joshua Seixas? Exploring the Influence of Hebrew Study on the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language," May 9, 2019

- "Egyptomania and Ohio: Thoughts on a Lecture from Terryl Givens and a Questionable Statement in the Joseph Smith Papers, Vol. 4," May 13, 2019

- "More on the Impact of Hebrew Study on the Kirtland Egyptian Papers: Hurwitz and Some Curiousities in the GAEL," May 20, 2019

- "He Whose Name Cannot Be Spoken: Hugh Nibley," May 27, 2019

- "More Connections Between the Kirtland Egyptian Papers and Prior Documents," May 31, 2019

- "Update on Inspiration for W.W. Phelps' Use of an Archaic Hebrew Letter Beth for #2 in the Egyptian Counting Document," June 16, 2019

- "The New Hauglid and Jensen Podcast from the Maxwell Institute: A Window into the Personal Views of the Editors of the JSP Volume on the Book of Abraham," July 1, 2019

- "The Twin Book of Abraham Manuscripts: Do They Reflect Live Translation Produced by Joseph Smith, or Were They Copied From an Existing Document?," July 4, 2019

- "Kirtland's Rosetta Stone? The Importance of Word Order in the 'Egyptian' of the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language," July 18, 2019

- "The Twin BOA Manuscripts: A Window into Creation of the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language?," July 21, 2019

- "A Few Reasons Why Hugh Nibley Is Still Relevant for Book of Abraham Scholarship," July 25, 2019

Continue reading at the original source →