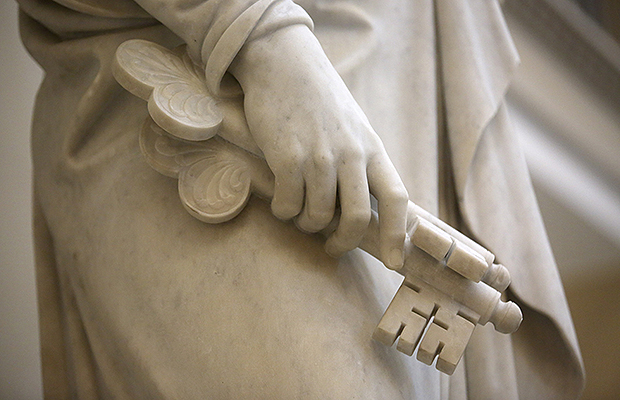

As my contribution to your home centered study of 1 and 2 Thessalonians this week, I theorize about what happened to early Christianity after the death of the apostles. As leadership in the early Church transitioned from apostles to local bishops, the priesthood keys[1] bestowed on Peter(Matthew 16:19) and the apostles (Matthew 18:18) were lost. The primary evidence of the apostasy is modern revelation. Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery claimed to have received visits from heavenly messengers and we are challenged to prayerfully seek after their own spiritual witness of claims regarding authority. An examination of ancient history can at best demonstrate plausibility and not proof of the apostasy. Those expecting the latter-day church is a carbon copy of an ancient church organization will be disappointed.[2]

Here are 10 thematic variations exploring the loss of priesthood keys.

- In Acts, Matthias was chosen to replace Judas can be beneficial.Proponents arguing for a restored gospel often generalize from that the apostles were meant to continue as the governing body of Christ’s church, replacing apostles who died or apostatized. This practice of maintaining the quorum of Twelve did not continue for long and LDS thinkers have commonly attributed this to persecution and widespread (but not universal) rejection of the apostles.

- There is also New Testament evidence for other apostles like Paul, James the brother of Jesus, Barnabas, etc.There is some different takes by non-Mormons about what to do with these additional apostles, which I sampled 10 years ago on the FairMormon blog .

- Some argue that apostles were no longer necessary after these as they had served their purpose in laying the foundation of the Church (for example Catholic Francis Sullivan[3]).

- Some believe that soon no one could meet the requirement (read into Matthias’s selection) that an apostle had to have been a living witness to Christ’s mortal ministry.

- Some postulate that the new apostles weren’t necessarily members of the Twelve (Episcopalian Bruce Chilton and Rabbi Jacob Neusner[4]). There is some early Christian evidence that Seventies could also be considered apostles and other special witnesses of Christ could likewise be considered apostles (see Mormon writer John Tvedtnes’s citations[5]).

- Refreshingly, one non-Mormon author argues that the Twelve as a governing body headquartered in Jerusalem were meant to continue, but eventually Roman persecution drove the Christians out of there (Baptist R.A. Campbell[6]).

- What is Matthew 16:18’s “rock” that the Church will be built and maintained upon? Both Protestants and Catholics typically use the passage as a guarantee the Church will never be taken from the earth and conclude that they must have the “rock.” Mormons tend to read it as a conditional promise, and the Apostasy is evidence that Christianity no longer possessed the rock. Catholics often identify the rock with Peter’s apostleship and conclude that Bishops (and more specifically the Pope) must be apostolic successors. Protestants sometimes contend the rock is Christ and a special priesthood is not strictly necessary. Mormons occasionally look at the context of Matt. 16:18 and conclude the rock is a symbol for revelation while denying that the Church continued purely intact on the earth. The gates of Hell[7] are associated with the Spirit World and more specifically the ones that prevent or delay resurrection. Note that Christ ultimately triumphed over these gates. Metaphorically a spirit’s death and resurrection is symbolic for a Church’s apostasy and restoration.

- In Ephesians, prophets and apostles were presented as the living foundation of the Church.Jesus is the chief cornerstone. A pair of scholars (Draper[8] and Mathewson[9]) developed these concepts even more. They use ancient Judeo-Christian texts to show the twelve apostles were associated with revelation, symbolically connecting the apostles with the High Priest’s stones (12 stones representing the tribes and the Urim and Thummim), with restored temple worship (as stone temple pillars), and are princes and judges over Israel (symbolically gatekeepers).

- Another thing lost or at least greatly modified in content and presentation with the loss of apostles was a priestly gnosis or body of knowledge related to the temple and heavenly ascents. Hugh Nibley had an interesting quip[10]:

“There are three periods in the history of the church,” writes Cyril, that of Christ, that of the apostles and”–we wait in eager anticipation for the successor in the leadership, but in vain–“those times which have passed since the apostles.” What a strange way to designate the third period of the church. It is as disappointing as Clement’s announcement that Christ gave the gnosis to Peter, James, and John; they passed it on “to the rest of the Twelve” and they in turn “passed it on to the Seventy.” Since the discussion is of the transmission of the key–the knowledge of the gospel–we wait for the next link in the chain, but there is none.

- In the New Testament, apostles are noted as the only deterrent from preventing false teachers from corrupting the Church from within. I am thinking specifically about Acts 20:29, but the book Early Christians in Disarray[11] has an appendix of New Testament passages on apostasy. There is also a 4th century early Christian historian, named Eusebius, who confirms this and it is cited in a Nov. 1972 Ensign article[12] :

Besides this, the same man, when relating the events of these times, adds that until then the Church had remained a pure and undefiled virgin, since those who attempted to corrupt the sound rule of the Saviour’s preaching, if any did exist, until then lurked somewhere in obscure darkness. But when the sacred band of the Apostles had received an end of life in various ways, and that generation of those who were deemed worthy to hear the divine wisdom with their own ears had passed away, then the league of godless error took its beginnings because of the deceit of heretical teachers who, since none of the Apostles still remained, attempted henceforth barefacedly to proclaim in opposition to the preaching of truth the knowledge falsely so-called.

- The great commission to the apostles was to do missionary work Matt. 28:19-20.Yet their supposed successors, the Bishops, had been primarily stationary overseers over local congregations looking after temporal needs when an apostle was present and taking charge of meetings in limited way during an apostle’s absence. This difference between an apostle and a bishop is crucial in Hugh Nibley’s Apostles and Bishops in Early Christianity and in Catholic Francis Sullivan’s book. Another good resource is an Ensign article[13] on early Christian bishops Polycarp, Clement, and Ignatius who did not regard themselves as having the authority the apostles had.

- Apostasy is more correctly thought of as a mutiny than merely a falling away.Notice that local leaders reject John and refuse to accept his letters in 3 John 1:19. I suggest this example is indicative of a wider trend where wealthy local leaders began to resent traveling apostles and prophets supervising them. Local leaders abused tests to detect false prophets (and revelation) to reject true prophets as well. I cover this source of tension in a blog primarily citing non-LDS scholar David Horrell[14].

- It is also clear in early Christian writings that Christians were also rebelling against the local leaders whom the apostles had appointed.John Tvedtnes has a good article covering this.

- It is also important to note that there were factions within the early church that didn’t like each other.Even the apostles sometimes didn’t get along very well. See John Welch’s chapter[15] in Early Christians in Disarray. In a blog I noted that Raymond Brown in Antioch and Rome[16] and John Painter in Just James[17] have created a categories of different factions regarding missionary policies. Brown speculated that the death of Peter and Paul in Rome under Nero was a conspiracy by envious Christians who disagreed with their policies.

References

[1] S. Kent Brown, “Peter’s Keys,” in The Ministry of Peter, the Chief Apostle: The 43rd Annual Sidney B. Sperry Symposium. Edited by Frank F. Judd Jr., Eric D. Huntsman, and Shon D. Hopkin. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014.

[2] Grant Underwood, “The ‘Same’ Organization that Existed in the Primitive Church” in Go Ye into All the World: Messages of the New Testament Apostles: The 31st Annual Sidney B. Sperry Symposium. Edited by Ray L. Huntington, Patty Smith, Thomas A. Wayment and Jerome M. Perkins. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2002. Kevin Barney, “A Tale of Two Restorations” FairMormon Conference, 1999.

[3] Francis A. Sullivan. From Apostles to Bishops: The Development of the Episcopacy in the Early Church. New York/Mahwah, N.J: The Newman Press, 2001. This book was panned by Michael C. McGuckian “The Apostolic Succession: A Reply to Francis A. Sullivan.” New Blackfriars 86, no. 1001 (2005): 76-93, but praised by Richard McBrien, “Debate over Role of ‘Bishop’ in Apostolic Succession Is a Church-Dividing Issue,” National Catholic Reporter, Vol. 44, No. 28, September 19, 2008.

[4] Bruce Chilton and Jacob Neusner in Types of Authority in Formative Christianity and Judaism. London, UK: Routledge, 1999.

[5] John A. Tvedtnes, “Scripture insight: ‘The Lord Appointed Other Seventy Also’” Insights, Vol. 19, No. 4

Provo, Utah: Maxwell Institute, 1999.

[6] R. Alastair. The Elders. New York City: T&T Clark International, 2004.

[7] Jack P. Lewis. “’ The Gates of Hell Shall Not Prevail Against It’(Matt 16: 18): A Study of the History of Interpretation.” Journal – Evangelical Theological Society 38 (1995): 349-368.

[8] J. A. Draper, “The Apostles as Foundation Stones of the Heavenly Jerusalem and the Foundation of the Qumran Community” Neotestamentica 22 (1988)

[9] David Mathewson, “A Note on the Foundation Stones in Revelation 21.14, 19-20” [JSNT 25.4 (2003) 487-498]. An LDS perspective can be found by Matthew Grey, “Priestly Divination and Illuminating Stones in Second Temple Judaism” in The Prophetic Voice at Qumran, pp. 21-57. BRILL, 2017.

[10] Hugh W. Nibley, Apostles and Bishops in Early Christianity (2005) p. 209

[11] Reynolds, Noel B., “Early Christians in Disarray: Contemporary LDS Perspectives on the Christian Apostasy” (2005). Maxwell Institute Publications.

[12] Hyde M. Merrill, “The Great Apostasy as Seen by Eusebius,” The Ensign, Nov. 1972.

[13]Richard Lloyd Anderson, “Clement, Ignatius, and Polycarp: Three Bishops between the Apostles and Apostasy,” The Ensign, Nov. 1976.

[14] David Horrell, “Leadership Patterns and the Development of Ideology in Early Christianity” Sociology of Religion v58 p. 323-41 Winter ’97.

[15] John W. Welch, “Modern Revelation: A Guide to Research about the Apostasy”

[16] Raymond E. Brown and John P. Meier. Antioch and Rome: New Testament Cradles of Catholic Christianity. Paulist Press, 1983.

[17] Painter, John. Just James: the brother of Jesus in history and tradition. Univ of South Carolina Press, 2004.

The post A Guide to the First Century Apostasy appeared first on FairMormon.

Continue reading at the original source →