“At about the age of twelve years,” Joseph Smith wrote, “my mind became seriously impressed with regard to the all important concerns for the welfare of my immortal soul.”

Living in upstate New York in the 1810s, Joseph was surrounded by religious discussion and controversy. Religious revivals put the urgent question “What must I do to be saved?” foremost in his mind. But the answer was elusive. “Being wrought up in my mind,” Joseph studied the “different systems” of religion, but “I knew not who was right or who was wrong and considered it of the first importance that I should be right in matters that involve eternal consequences.” His own sins and the “sins of the world” made him “exceedingly distressed.”

By “searching the scriptures,” Joseph learned that “mankind did not come unto the Lord but that they had apostatized from the true and living faith and there was no society or denomination that built upon the gospel of Jesus Christ as recorded in the New Testament.”

For a time, Joseph Smith sought relief among the Methodists. In July 1819, more than one hundred ministers gathered for a conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, convened in Vienna (now Phelps), New York, a half-day’s walk from the Smith family farm. The area pulsed with “unusual excitement on the subject of religion.”

The preaching of one of the ministers, George Lane, may have especially influenced Joseph. William Smith, Joseph’s younger brother, recalled that Lane “preached a sermon on ‘What church shall I join?’ And the burden of [Lane’s] discourse was to ask God, using as a text, ‘If any man lack wisdom let him ask of God who giveth to all men liberally.’”

Joseph felt “partial” toward the Methodists but resisted full association; he wanted to know which doctrine was right.

He refused to feign conversion or religious feeling. Joseph later told friends that during one Methodist meeting “he wanted to feel and shout like the rest but could feel nothing.” Yet he was “greatly excited; the cry and tumult were so great and incessant.”

“During this time of great excitement,” Joseph’s religious concerns became a crisis.

He wondered in his head whether the churches were “all wrong together” but resisted letting the awful thought enter his heart. At the same time, he experienced “confusion,” “extreme difficulties,” and “great uneasiness” caused by guilt for his sins in the midst of a bewildering “war of words and tumult of opinions” about which church could furnish him with forgiveness.

Joseph was also grieved because of the disparity he found between the churches and the Bible.

Indeed, the Bible was both the battleground of this war and its greatest casualty, “for the teachers of religion of the different sects understood the same passage of scripture so differently as to destroy all confidence in settling the question by an appeal to the Bible.”

Yet it was the Bible’s God to whom Joseph appealed.

He had listened over and over as religious partisans wielded the Bible as a weapon, “endeavoring to establish their own tenets and disprove all others.” Now Joseph approached the Bible privately, quietly—as a living word rather than as a dead law—and it spoke to his seeking soul.“Laboring under the extreme difficulties caused by the contests of these parties of religionists,” Joseph read James 1:5:

“If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not; and it shall be given him.”

The passage sank powerfully into his consciousness.

“Never did any passage of scripture come with more power to the heart of man than this did at this time to mine. It seemed to enter with great force into every feeling of my heart. I reflected on it again and again,” Joseph said, “knowing that if any person needed wisdom from God, I did; for how to act I did not know, and unless I could get more wisdom than I then had, I would never know.”

The biblical invitation to seek revelation moved Joseph deeply.

The biblical invitation to seek revelation moved Joseph deeply.

Joseph’s culture was so prone to proof texting—proving various doctrines with passages from the Bible—that the invitation to seek wisdom directly from God was “cheering information,” as Joseph called it, “like a light shining forth in a dark place.” Joseph determined to pray aloud for the first time in his life.

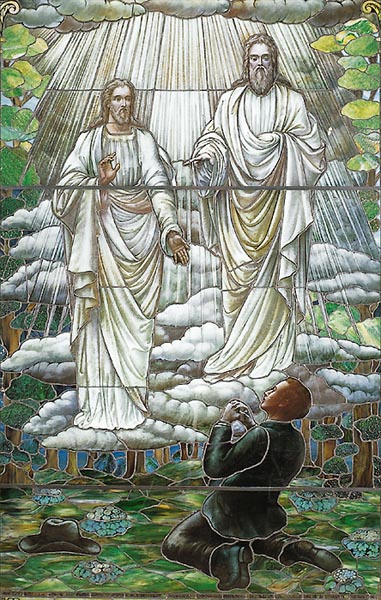

On a clear spring morning in 1820, Joseph sought solitude in the woods near his home.

He went to a familiar place, near the “stump where I had stuck my axe when I had quit work,” he said. There he knelt and began searching for words to express his deepest desires, but he was overcome by an unseen power.

Tongue-tied and enveloped by thick darkness

Joseph felt doomed as he was “seized” by the astonishing “power of some actual being from the unseen world, who had such marvelous power as I had never before felt in any being.” This adversary “filled his mind with doubts and brought to mind all manner of distracting images.” At the moment when he had to choose whether or not he would succumb to the force that held him, Joseph exerted “all my powers to call upon God to deliver me out of the power of this enemy.”

Joseph became conscious of a heavenly light descending upon him, growing more brilliant as it enveloped him and the leaves and boughs of the trees, until they seemed to be consumed with fire and the light was brighter than the sun.

It rescued Joseph from his unseen enemy. Darkness vanished. Joseph’s prayer opened heaven and invoked power that vanquished the most potent opposing force he had ever experienced. In the midst of the “pillar of fire,” Joseph saw a glorious personage standing above him in the air. He called Joseph’s name and said,

“This is my beloved Son. Hear him.”

Joseph saw another personage appear who “exactly resembled” the first. The Son then called Joseph by name and said, “Thy sins are forgiven.”

Joseph asked the heavenly beings which church was right.

“Must I join the Methodist Church?” he asked. “I was answered that I must join none of them, for they were all wrong.” The problem was that “all religious denominations were believing in incorrect doctrines.” God did not acknowledge any of them “as his church and kingdom.” The everlasting covenant, the tie between the ancient Christian gospel and the present day, “had been broken.”

Jesus Christ confirmed Joseph’s observations

“The world lieth in sin,” He told Joseph. The existing churches had “turned aside from the gospel and keep not my commandments. They draw near to me with their lips while their hearts are far from me.”

The “creeds” that oriented the Christian churches were “an abomination” in God’s sight.

They claimed God was unknowable and incomprehensible, yet He was revealing Himself to Joseph Smith in answer to prayer. One creed said, in the language of the philosophers, that God was “without body, parts, or passions.” Yet Joseph Smith saw and heard personages and felt Their overwhelming love.

“My soul was filled with love,” Joseph wrote with his own pen, “and for many days I could rejoice with great joy and the Lord was with me, but [I] could find none that would believe the heavenly vision nevertheless I pondered these things in my heart.”

Joseph Smith had found what he “most desired.” He “had found the testimony of James to be true, that [anyone] who lacked wisdom might ask of God and obtain.” The answer to his prayerful quest was not the experience the revival preachers encouraged or perhaps that Joseph expected. There were no “shouts of rejoicing,” no bench to sit on while the faithful prayed for him to get religion, no “deep tones of the preacher.” There was just Joseph in the “wilderness,” acting on the Bible’s oft-repeated invitation to revelation: ask and receive.

Read the four primary accounts of Joseph’s First Vision on which this narrative is based:

1838 Account (Pearl of Great Price)

*This post was originally published on the Church’s site in 2016

The post The First Vision: A Narrative from Joseph Smith’s Accounts appeared first on Steven C. Harper.

Continue reading at the original source →