The Know

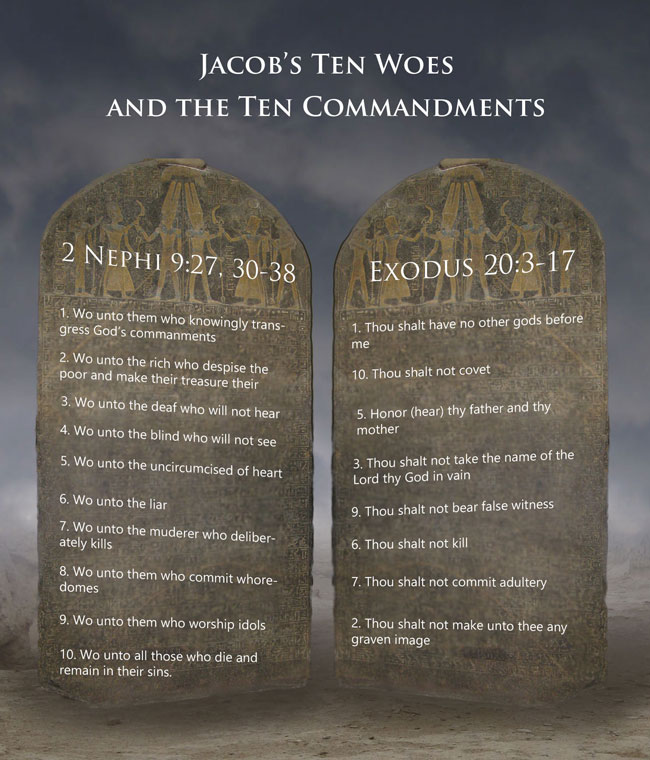

Shortly after the Nephites built their first temple in the New World and asked Nephi to be their king, Nephi consecrated his brothers Jacob and Joseph as priests and asked Jacob to address the people (2 Nephi 5:16–18, 26; 6:1–4). The occasion of Jacob’s speech was most likely during one of the biblically prescribed autumn festivals, during which the Nephites would have formally crowned Nephi as their earthly king and covenanted loyalty to the Lord as their true king.1 As part of his address, Jacob pronounced ten “woes” that parallel the Ten Commandments (2 Nephi 9:27–38).2

Image by Book of Mormon Central

Interestingly, another set of Ten Words or Commandments, as they are called in Exodus 34:27–28, are found in Exodus 34:14, 17–23, 25–26. This list is more interested in sacrificial and ritual practices, although commandments 1, 2, and 6 have counterparts in the basic Decalogue in Exodus 20. In brief, the commands in Exodus 34 are as follows:

- Thou shalt worship no other god.

- Thou shalt make thee no molten gods.

- The feast of unleavened bread thou shalt keep.

- All the firstborn of thy sons thou shalt redeem.

- None shall appear before me empty.

- On the seventh day thou shalt rest.

- Thou shalt observe the feast of weeks.

- Thrice in the year shall all your men children appear before the Lord

- Thou shalt not offer the blood of my sacrifice with leaven.

- Thou shalt not seethe a kid in his mother’s milk.

The existence of these two related, but distinct, sets of commandments in the book of Exodus, shows that the list of commandments could be adjusted over time or to suit the needs of the people in different circumstances.

According to Moshe Weinfeld, the Ten Commandments in Exodus 20 were “the foundation document of the Israelite community.” They were given to Moses on Sinai, “at the dawn of Israelite history,” as the basis of God’s covenant with Israel (Exodus 20:2–17).3 Thus, Weinfeld argues, “They set forth the basic conditions for inclusion in the community of Israel,” and comprise “the essence of God’s demands from his confederates.”4 As such, these commandments were read during Israelite festivals as part of the renewal of their covenants with the Lord at the temple.5

Similarly, Jacob’s ten “woes,” pronounced on a festival occasion, at the dawn of Nephite history, likely served a comparable function for the Nephite people. John W. Welch explained:

His “ten woes” function as the equivalent of a contemporaneous Nephite set of ten commandments. His statement is an admirable summary of the basic religious values of the Nephites, cast in a form fully at home in ancient Israel and in the Near East.6

And like the commandments in Exodus 34, Jacob’s list is likewise not merely a repeat or “thoughtless copy of the biblical ideals.” Instead, “Jacob’s principles have been tailored as a revelation to his people and their needs.”7

An example of how Jacob intelligently adapted and clarified the original Decalogue is found in his seventh “woe,” parallel to the sixth of the Ten Commandments: “Thou shalt not kill” (Exodus 20:13; Deuteronomy 5:17), recast by Jacob as, “Wo unto the murderer who deliberately killeth, for he shall die” (2 Nephi 9:35, emphasis added).

Speaking at or near the time of Nephi’s coronation, “Jacob could not likely have commented on the law of homicide without Nephi’s slaying of Laban coming to mind.”8 Indeed, some of the very emblems of Nephite kingship—such as the plates of brass and Laban’s sword—were obtained by means of Nephi slaying Laban.9 As Welch observed, under these circumstances, “Categorically cursing all people who killed … would have been extremely undiplomatic,”10 and therefore Jacob would have naturally included the qualifying word “deliberately” to distinguish the basic law of homicide from Nephi’s unusual but legally distinguishable case.

Nephi carefully related the incident of Laban’s slaying in order to show that the Lord delivered Laban into his hands, making his actions unpremeditated and protectable under the homicide law of Exodus 21:12–14 (1 Nephi 4).11 Thus, Nephi’s slaying of Laban was not deliberate in the sense of involving “deliberation, lying in wait, or other similar planning and hatred,” and was nonculpable under Israelite law.12 What this meant in practice was that he and other such manslayers were authorized to flee, taking asylum in a city of refuge, or could flee from the holy land entirely, which is what Nephi and all of Lehi’s family did.

The Why

As discussed above, both sets of Ten Commandments in the Old Testament, and also Jacob’s ten woes in the Book of Mormon, probably functioned as “a set of concise basic obligations directed at all members of the Israelite [or Nephite] community, connected by a special covenant with God.”13 In this regard, these commandments or woes function in a manner similar to the questions asked by Latter-day Saint bishops and stake presidents in baptismal and temple recommend interviews, which is to identify the basic standards by which one must live to be a member of the Latter-day Saint community in good standing, to be worthy to enter the holy temple, and to make certain covenants with God.

These scriptural sets of moral injunctions also pertain to holiness, worthiness, and faithfulness. President Russell M. Nelson recently explained that the Lord “has directed what each person must do to qualify to enter His holy house,” stressing that, “All requirements to enter the temple relate to personal holiness.”

While the Lord’s standards remain steady and consistent, in the October 2019 conference, President Nelson announced that some of the temple recommend interview “questions have recently been edited for clarity.”14 Both Jacob’s inspired reformulation and adaptation of the original Ten Commandments into “a set of principles relevant to his people and their cultural needs and concerns,”15 and existence of second set of “ten commandments in Exodus 34 illustrate that this process and the need to clarify God’s laws and standards through His authoritative priesthood leader, given to his people in changing times and circumstances, is ancient and comports with scriptural precedent.

Just as Jacob’s clarification that it is the deliberate murderer who is condemned by the law is consistent with the original intent of God’s homicide laws to the Israelites (see Exodus 21:13–14), and also made clear how that original intent should be explicitly understood where questions might be expected to arise, so the recent updates and clarifications made by the Lord’s servants to the temple recommend questions remain consistent with God’s standards of worthiness established for entering the temple today.

Further Reading

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does Jacob Declare so Many ‘Woes’? (2 Nephi 9:27),” KnoWhy 35 (February 17, 2016).

John W. Welch, “Jacob’s Ten Commandments,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 69–72.

John W. Welch, “Legal Perspectives on the Slaying of Laban,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 1, no. 1 (1992): 119–141.

- 1. See Book of Mormon Central, “Did Jacob Refer to Ancient Israelite Autumn Festivals? (2 Nephi 6:4),” KnoWhy 32 (February 12, 2016). For more information, see John S. Thompson, “Isaiah 50–51, the Israelite Autumn Festivals, and the Covenant Speech of Jacob in 2 Nephi 6–10,” in Isaiah in the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 123–150.

- 2. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does Jacob Declare so Many ‘Woes’? (2 Nephi 9:27),” KnoWhy 35 (February 17, 2016). For more information, see John W. Welch, “Jacob’s Ten Commandments,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 69–72. See also John W. Welch, “Counting to Ten,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 12, no. 2 (2003): 48–49.

- 3. Moshe Weinfeld, “What Makes the Ten Commandments Different?” Bible Review 7, no. 2 (April 1991): 41.

- 4. Weinfeld, “What Makes the Ten Commandments Different?” 37, 38.

- 5. Weinfeld, “What Makes the Ten Commandments Different?” 41. For a more detailed treatment of these ideas, see Moshe Weinfeld, “The Decalogue: Its Significance, Uniqueness, and Place in Israel’s Tradition,” in Religion and Law: Biblical-Judaic and Islamic Perspectives, ed. Edwin Firmage, Bernard G. Weiss, and John W. Welch (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1990), 3–47.

- 6. Welch, “Jacob’s Ten Commandments,” 72.

- 7. Welch, “Jacob’s Ten Commandments,” 70.

- 8. Welch, “Jacob’s Ten Commandments,” 71.

- 9. See Brett L. Holbrook, “The Sword of Laban as a Symbol of Divine Authority and Kingship,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2, no. 1 (1993): 39–72; Brett L. Holbrook, “Sword of Laban as a Symbol of Divine Authority,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 93–96; Gordon C. Thomasson, “Mosiah: The Complex Symbolism and Symbolic Complex of Kingship in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2, no. 1 (1993): 21–38.

- 10. John W. Welch, “Legal Perspectives on the Slaying of Laban,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 1, no. 1 (1992): 138.

- 11. Book of Mormon Central, “Was Nephi’s Slaying of Laban Legal? (1 Nephi 4:18),” KnoWhy 256 (January 2, 2017). See also Welch, “Legal Perspectives on the Slaying of Laban,” 119–141; John W. Welch, “Narrative Elements in Homicide Accounts,” Jewish Law Association Studies 27 (2017): 206–238; John W. Welch, “Homicides in the Old Testament and the Book of Mormon,” Clark Memorandum, Fall 2018, 22–35.

- 12. Welch, “Legal Perspectives on the Slaying of Laban,” 138.

- 13. Weinfeld, “What Makes the Ten Commandments Different?” 40.

- 14. President Russell M. Nelson, “Closing Remarks,” October 2019 General Conference, online at churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 15. Welch, “Jacob’s Ten Commandments,” 72.

Continue reading at the original source →