I’ve been asked how to tolerate the unprecedented uncertainty we face today.

We are certainly awash in uncertainty and tolerance is a tried and true academic response. But the kind of tolerance to which modern universities are a temple isn’t the kind of tolerance we really need. The tolerance that concedes another’s right to a differing opinion is kindergarten-level pluralism — a thin gruel that can’t sustain us for the challenges we face.

The real tolerance we need today is suggested by the word’s Latin root: Tolerance means the ability to “bear pain and hardship.” Think of load tolerance. In this post-pandemic world, we need this ability to bear pain.

Some people are terrific at this. They absorb enormous amounts of pain on their way to personal achievement. They metabolize pain and convert it into gold stars. They put in extra hours at the gym, the office and the library. They brag about CrossFit, sleep deprivation or eating kale (which is more painful). This is the grit that underwrites the truth: No pain, no gain. But I’m not talking about bearing this kind of pain. That’s not what the world needs today.

To be useful in this world, we need more than the ability to bear our own pain.

I’m not even talking about the truth that you will all bear real personal pain; it’s true we live in a fallen world where pain and fracture keep us from bliss or the beatific vision. And you will one day all face (and need to bear and tolerate) the pain of prejudice, racial injustice, economic distress, failure, illness, isolation, the pain of being misunderstood, falsely accused or correctly accused. Your challenge will be to bear this personal pain and carry it without breaking. You will have to avoid this culture’s insistent invitation to shrug off that pain and drop it into dark pools of blame, alcohol, sex, greed and ambition.

But to be useful in this world, we need more than the ability to bear our own pain. We need to carry the pain of other people. There’s a reason that the word bear (as in “bear pain”) is etymologically and conceptually related to the idea of bearing children; pain borne for others is productive and life-sustaining — even redeeming.

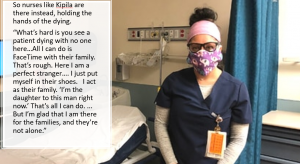

Surely the quarantine has taught us that. We’ve seen people who spent their time in a “quarantine cocoon” wrapped in silent self-concern, thinking only of sourdough and “Tiger King.” But then we’ve also seen health care workers, ordinary men and women, who have left the safety of their homes and gone to hospitals to hold the pain and hold the hands of the dying. I’ve read about nurses who left home to volunteer at overloaded hospitals, to sit with the dying and hold their hands — who are willing to sit with strangers, and put themselves in their shoes and say, “They are also my family. I am the daughter to this man right now” — men and women who stay after work to hold the hands of people as they pass.

Surely we have seen this essential truth from these essential workers. Being alive means you must suffer. But being worth something, being essential, means you suffer for others — and with others.

This is what it means to be essential — to be essentially human, to lift the pain of others you are free to ignore. Our lives are defined by the pains we volunteer to bear. This is a core of the Christian message.

The (perhaps for some) unsettling truth is that for many things — even many essential things — you don’t need a law degree or even a college degree or special skills. What you need is to be willing. So direct your gaze in any direction, set out and you will see pain, racial injustice, violence, the desperation of the world’s poor, the mentally ill and the lonely. Perhaps your generation’s gift is the ability to bear others’ pain. Offer to help, listen, hold their hands, give money, pass laws, but I beg you to not settle for being comfortable or rich or important. Be essential. Be tolerant. Bear the pain of those you might be free to ignore.

Our lives are defined by the pains we volunteer to bear.

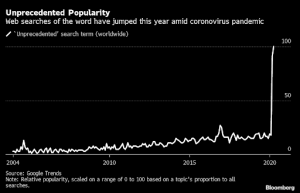

Unprecedented Times

Many of us feel that we are not just living through uncertainty, but in unprecedented uncertainty. At the very least, we are awash in unprecedented use of the word unprecedented.

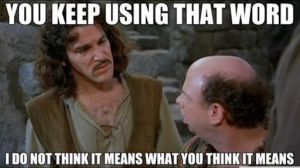

But to this, I want to say, following the wisdom of The Princess Bride, “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”

If you are feeling this way, if you are feeling adrift and without guidance, I want to tell you that you have forgotten the first rule of the first-year law student: Hide in the back row.

No, wait, I mean, look for precedent.

Not all of us can enter hospitals, cure disease, or hold the hands of the dying. But law students should at least be able to look for precedent.

And I think there actually is precedent for our situation and the uncertainty that we face. And I think that with this precedent, there is reason to hope.

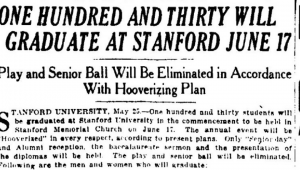

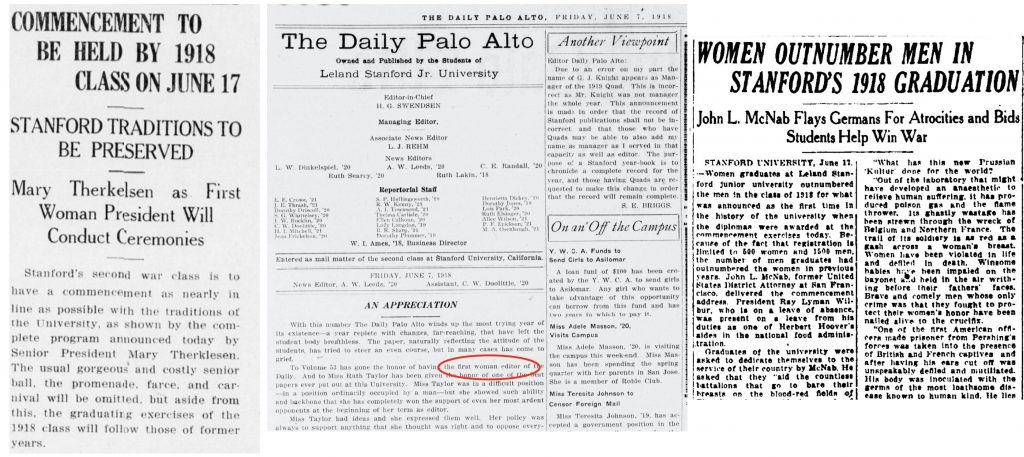

Consider the graduating class of 1918. I recently dug into the accounts of students who graduated from Stanford Law School in 1918. Their graduation day was unusual and difficult. Traditional celebrations and farewells were canceled and their commencement was stripped down to the bones. The newspapers euphemistically said that these celebrations had been “Hooverizing”, which meant—for those of you more familiar with vacuum cleaners than former presidents—it sucked.

Why all these cancelled plans? Well, for one thing, war. Graduates of 1918 faced a brutal world war and naturally there were fewer resources for celebrations. And there was reason perhaps to avoid big celebrations; war took the lives of many classmates and, of course, the world-wide influenza pandemic later took many more.

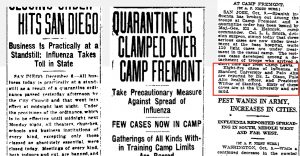

Reading the newspaper headlines from 1918, I was struck by how similar the outlines of their life was to ours. Newspapers reported the number of new cases every day. The pandemic brought business to a standstill, creating political controversy about the need for restrictions.

Reading the newspaper headlines from 1918, I was struck by how similar the outlines of their life was to ours. Newspapers reported the number of new cases every day. The pandemic brought business to a standstill, creating political controversy about the need for restrictions.

The unscrupulous profited from the uncertainty by hawking dubious miracle cures and quarantine weight-loss gimmicks, while the entrepreneurial offered distance learning alternatives (back then Zoom was a home correspondence course).

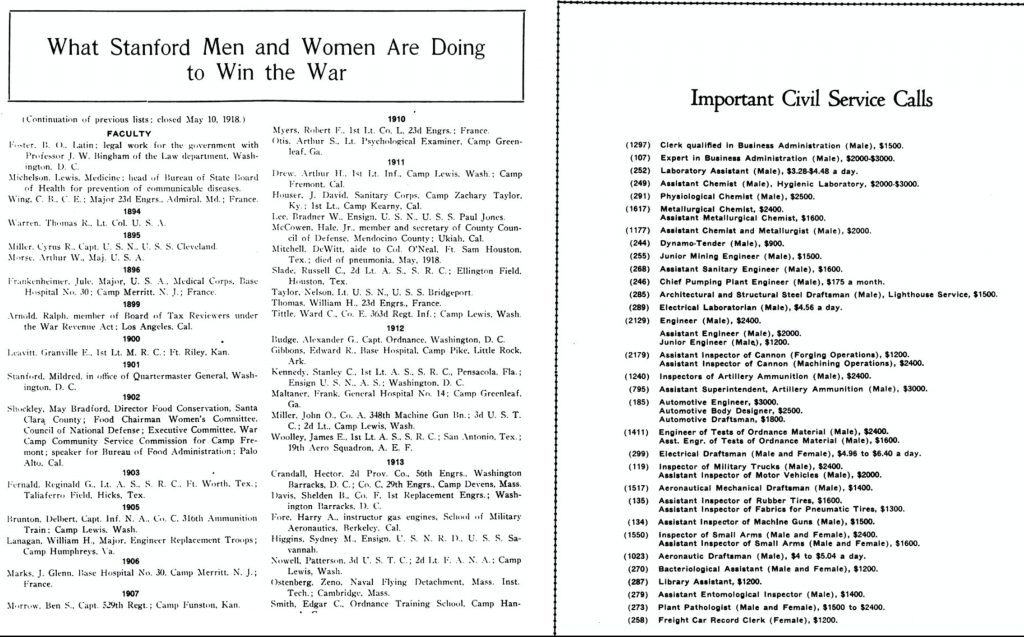

All this makes me hopeful, because in some ways, things haven’t changed much. We don’t have time to recount the lives of the graduates that I followed, but ordinary men and women met these challenges, bearing others pains, and doing ordinary tasks in hard times – and they made an enormous difference in the world, helping people suffering from poverty and addiction.

Think for a moment about what the Class of 1918 would face over the next 20 years. In the time it took us to go from Destiny’s Child to Beyonce, the class of 1918 faced the pandemic, the collapse of the financial system and the Great Depression, and then ultimately World War II. That’s a pretty grim next twenty years.

And yet they got through it. They faced enormous challenges to democracy, equality, health, and human happiness. And they got through it. And even amidst these dark and tumultuous events, you can now, looking back, see seeds of hope— women taking positions that had been previously denied them and the people reinforcing the value of public service and civic duty.

Uncertainty

Now, I’m out of time. I should say something about uncertainty, but there is not time to say anything that doesn’t sound trite.

I’ll say only this. Uncertainty is a given and must be tolerated, but not chaos. It is therefore important (and easy) to condemn public figures and private villains that seek and profit from chaos. Moreover, although we face irreducible uncertainty (when will the pandemic “end”? Is there a drug to stop the disease?) the potential for real chaos and the greatest damage comes not from the virus, but from our reactions; the danger is “internal” in this sense rather than only external.

Beware and mistrust the pleasurable rush of self-righteous certainty that comes from morally condemning those who disagree with us.

For me the question is how to limit this chaos in order to protect vulnerable individuals and valuable institutions. And while the pandemic has rolled across our world and threatened to flatten our social, economic and political institutions, it seems to me that the people who have done the most good are those who are able to work with others with whom they disagree (think Anthony Faucci). Most questions about social organization have no easy answers and we have to choose between competing goods (personal responsibility and compassion, order and liberty).

Therefore, to create something valuable, to build rather than to cause chaos, we must beware and mistrust the pleasurable rush of self-righteous certainty that comes from morally condemning those who disagree with us. Decrying their moral repugnance gives us deeply satisfying relief, but this is a false relief and can, I fear, lead to chaos. We must remind ourselves to assume (and thereby to encourage) the good faith of others who oppose and criticize us.

Conclusion

So I’ll end here: Tolerate pain. Be essential. Uncertainty does not mean chaos, so build bridges to (and with) those who disagree with you.

And remember that there are many reasons to hope. People in pandemics have done brutally difficult things. Ordinary men and women have protected democracy, survived, and fought for equality.

And so can you.

The post Tolerating the Unprecedented appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →