Who are you, really? And how do you go about finding that out? It turns out there are two radically different ways of answering that question. And as important as the ultimate answer to that question is, I would argue that how you answer that question is even more important than what the answer is. It affects everything about us, as well as how we relate to others, in even the most important aspects of our being: how we pursue love, perceive sexuality, and root our identity.

Who are you, really? And how do you go about finding that out? It turns out there are two radically different ways of answering that question. And as important as the ultimate answer to that question is, I would argue that how you answer that question is even more important than what the answer is. It affects everything about us, as well as how we relate to others, in even the most important aspects of our being: how we pursue love, perceive sexuality, and root our identity.

When it arrived in Europe in the late eighteenth century, Romanticism made a big splash. And its effects are still with us. More than just a philosophy, or an art form, it had a phenomenological (or psychological, though that word didn’t exist yet) component too. The Encyclopedia Britannica has an excellent summary of what this movement entailed:

Romanticism emphasized the individual, the subjective, the irrational, the imaginative, the personal, the spontaneous, the emotional, the visionary, and the transcendental.

Among the characteristic attitudes of Romanticism were the following: a general exaltation of emotion over reason and of the senses over intellect; a turning in upon the self and a heightened examination of human personality and its moods and mental potentialities… a focus on [an individual’s] passions and inner struggles; a new view of the artist as a supremely individual creator, whose creative spirit is more important than strict adherence to formal rules and traditional procedures; an emphasis upon imagination as a gateway to transcendent experience and spiritual truth; an obsessive interest in folk culture, national and ethnic cultural origins, and the medieval era; and a predilection for the exotic, the remote, the mysterious, the weird, the occult, the monstrous, the diseased, and even the satanic. (Emphasis added.)

The Appeal of Romantic Identity

I also need to introduce an important related term, poiesis—which is originally a Greek word meaning “to make.” In Romanticism, this word denotes the primary activity of the artist, which is to discover one’s distinctive individuality and then use that to create something unique. Rosaria Butterfield defines poiesis as “finding authenticity by inventing yourself on your own terms.” From this perspective, discovering and expressing one’s emotion and subjective experience is more important than any objective truth. What’s true is what is authentic to oneself; there is nothing more false or tragic than to live inauthentically.

Shakespeare seems to have anticipated this movement when he has Polonius say, “this above all: to thine own self be true.” The discovery of who I am is one’s highest quest, and it’s vital to get it right—to discover one’s true self. This is the work of a lifetime, and it can turn on a dime after experiencing some strong emotion which reveals an entirely new element of oneself. The intensity of the emotion is what determines one’s inner truth here—there is a risk that one could be mistaken, or one’s feelings can shift, but so long as one continues the relentless process of inner excavation, it will eventually lead to one’s “best life.”

This noble quest appears to conform to Socrates’ dictum, “the unexamined life is not worth living.” This journey of self-discovery, for the romantic, is the most significant work of one’s life.

It also becomes one of the greatest moral questions we face. We come to determine what is right and good for us by a process of introspection Like the “Potter Box” of ethics courses, where it’s expected that two different people could follow the same moral reasoning and come to entirely different conclusions. The Book of Judges describes a similar period of subjective moral judgment when it says, “In those days there was no king in Israel: every man did that which was right in his own eyes.”

T.S. Eliot’s beautiful lines from his poem “Little Gidding” evokes the poiesis with its most convincing garb (though Eliot was not really a Romantic):

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

All Is Not Well With Romanticism

This all sounds pretty good so far. But like in a Beethoven symphony, some dissonant chords begin to intrude, invoking a distant, gathering storm. For starters, the Polonius we love to quote is not an aspirational character. Shakespeare’s no Romantic—and he plays this character for laughs and doesn’t intend him to be taken seriously. That’s why Polonius is a fool and a bore. His speech is cliché-ridden, self-contradictory, and occasionally incoherent.

Another annoying dark cloud appears, following us around like Eeyore. Socrates was not describing mere introspection when he admonished his accusers to examine their lives. This counsel reflects Socrates’ adamant belief that “the greatest good of man is daily to converse about virtue.” Think of it instead like a cross-examination in front of an exacting judge: he’s inviting us to submit our morals and behavior to challenge and potential criticism if they fall short of ideal virtue. This is about a call to repentance and correction, not self-analysis. Tellingly, he refuses to back down (even in the face of death) because that would be “disobedience to a divine command.” He is more prophet than poet, with a message to deliver—even if that precipitated his own death. Socrates did not have a Potter Box, he got the executioner’s box.

Even larger and more forbidding clouds appear, and the landscape seems a little desolate, like in the moving Caspar David Friedrich painting headlining the article. We see the individual, and—fitting for a Romantic setting—he is at the center. He has climbed to a lofty peak, and he surveys a vast infinitude. But he’s also alone. And the landscape looks a little cold and forbidding.

This poiesis of identity formation is solitary work. Who else can really understand you, since you are unique, and the deeper you go into your journey within, you become only more so?

Now the clouds are dark and stormy. Portentous lightning and thunder appear, as the “Sorrows of Young Werther” takes the stage.

Henry Wallace’s“Death of Chatterton.” It illustrates some German editions of “The Sorrows of Young Werther.”

Though early, Goethe’s poem by that name was the quintessential Romantic poem. It describes our young “hero” suffering terrible emotional pain because he is in love with Charlotte, who is already engaged to another man. His suffering is not physical, but emotional. This is the downside to Romantic love, all this beautiful, intense passion: powerful, yes; captivating, definitely. Yet it also often makes you miserable. There is no guarantee that the object upon which you have fixed your love will love you back. And no guarantee that the love will remain, as you are tossed to and fro upon the stormy seas of emotion. There is no anchor in the sea of Romantic love. You are at the mercy of wherever the winds and the waves take you. The way some Romantics write about love, it sounds more like a serious bout of tuberculosis (the Romantic’s favorite disease): a period of weakness and suffering where powerful symptoms consume you, which you are powerless to prevent or treat. The affliction may persist for a

A watercolor by R. Cooper (1912) depicting“a sickly young woman dying of tuberculosis.”

protracted period of time, and sometimes you think you are cured, only to have it recur. Like tuberculosis, Romantic love is consumptive, not creative.

The highest aspiration you can hope for is to experience for yourself the kind of love that artists paint about, musicians sing about, and poets sigh over as they pen the next stanza. To live passionately is to live well, even if those passions lead to misery and even death. And to be vividly remembered is better than having a boring, but morally upright, life. (Needless to say, this prioritizing of emotion over reason would have Socrates turning over in his hemlock-ridden grave.)

Werther eventually shoots himself with two pistols and then lies in agony for twelve hours. He is buried between two lime trees, forever remembered for the Sturm und Drang of his life. But now our survey takes an especially, shall we say, Gothic, turn. The woods are now dark and deep.

Goethe’s poem caused a sensation throughout Europe. Young men were imitating Werther’s fashion sense and literary sensibilities. Their tempestuous emotions were a mark of manly up-to-the-minute fashion. Worse, the poem sparked a wave of copycat suicides. It seemed that any young man with a love affair gone bad was at risk of suicide, and since there is never a shortage of lovelorn young men, the authorities were justifiably alarmed. At least two countries, Denmark and Italy, banned its publication.

This pairing of desire with death (which Freud called “eros and Thanatos”) seems to be a fairly consistent feature of the Romantic outlook. In our constantly revised, ever-shifting process of identity formation, we try to ignore any wreckage from eros and Thanatos that may accrue to ourselves and others. Billy Joel highlights the danger and excitement of this pursuit when he sings:

Well we all fall in love

But we disregard the danger……

Everyone goes south

Every now and then…

You may never understand…

You will never quench the fire

You’ll give in to your desire

When the stranger comes along.

The Triumph of Illusion

Technological and medical advances have made this process of identity discovery even more plastic, and even more untethered from time-tested truth. Many of us spend most of our days staring at lighted, colorful screens, either working at our jobs or consuming a proliferating variety of entertainments and social media interactions. Many of us work in professions divorced from the rhythms of the seasons and the diurnal patterns of daylight and darkness, of phases of the moon, and insulated from the imminence of starvation and the brutality of animal slaughter. Medical advances like birth control pills and artificial insemination have divested sexual intercourse from its primary function and our species from its survival imperative to propagate itself. Now it is possible to eat strawberries in winter, work under artificial light at all hours, and have (apparently) consequence-free recreational sex. Our pursuits are largely untethered from objective reality and the cold equations of physical survival. Male and female are no longer inescapably tethered to their anatomy, wherein their complementary union makes reproduction possible because we can now create human beings in test tubes. If sex, pursued for recreational purposes, should accidentally result in the creation of a regretted fetus, abortion is always available, and the products of conception can be suctioned away, safely out of view.

When the poet Hesiod encounters the Muses of Olympus, they say to him:

Listen, you country bumpkins, you pot-bellied blockheads,

We know how to tell many lies that pass for truth,

And when we wish, we know to tell the truth itself.

“The School of Athens.” detail showing Plato (left) and Aristotle (right) from a fresco by Raphael, 1509-1511.

This is the problem: art can tell the truth if it wants to. But it can also tell lies that are practically indistinguishable from truth. Thus, TV shows depict guilt-free abortions or consequence-free casual sex. This is why in Plato’s idealized Republic, poetry was banned. He recognized its power to convey truth but did not feel that outweighed the dangers of its power to tell convincing lies. In contrast, consider how much of our gross domestic product is devoted to the creation of illusion: in advertising, music, plays, movies, and now the streaming services we binge-watch.

As part of this, we had to create a new term, virtual reality, to distinguish it from real reality. Virtual reality allows you to become whatever avatar you would like, with your race, appearance, age, and gender are as changeable as you wish. New “skins” are easily downloadable in video games, though often at a price. Even death is a temporary thing, as our avatars are respawned and recreated instantly.

It is only in an environment like this where marriage could possibly be reconceived as a therapeutic vehicle for self-actualization instead of its original purpose (as a stable structure for the rearing of children). It is only in a virtualized world that we could possibly believe sex was something arbitrarily assigned, and just as easily reassigned with the slice of a scalpel and the stroke of a legal pen. And only in an environment like this would adolescents have the burden of not only selecting a potentially life-altering college major and career but also must now choose among one of the proliferating numbers of genders and sexual orientations.

Rather than appreciating your unique individuality alone, introspection is now intended to lead to the discovery of which group identities you should align with. Each intersectional identity has its own bitterly reckoned balance sheet of privilege and oppression, but these combine in so many ways no one else can ever truly appreciate your own experience. As each intersectional identity seeks for the full scope of its victimhood to be recognized, disrespect and misunderstanding among competing intersectionalities become inevitable.

Mimesis: A Superior Alternative

The deeper problems of this Romantic method of identity discovery and formation become clearer when compared with its more ancient alternative. This concept of identity goes back to the very beginning, to the first chapter of Genesis: “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.” We might think of this as Mimetic identity, from the Greek word mimesis, meaning mimicry, or the act of resembling. Rosaria Butterfield defines this as “finding excellence by imitating something greater than yourself.”

“Adam’s Creation.” Sistene Chapel detail, by Michelangelo, 1509-1512.”

In our spirits, and in our bodies, we bear the image of God. This does not mean we are perfect like the divine, but it does mean we are “very good.” As image-bearers of Heavenly beings, we have a kind of godlike spark that points us to something infinitely greater than ourselves, and also beyond our own reach. As Robert Browning put it, “Man’s reach must exceed his grasp/Or what’s a heaven for?”

Throughout revealed scripture, the appearance of God, or even one of His messengers, is accompanied by awe and even fear. God’s glory is so great that many who are brought into that presence fear they will be consumed. When Moses came down from the mountain, his “face shone” and the Hebrews “were afraid to come near him.” As with certain of the angels, this may also be how our far-future selves could appear to us. As C.S. Lewis put it, “It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest most uninteresting person you can talk to may one day be a creature which… you would be strongly tempted to worship. … There are no ordinary people.”

If this is the nature and destiny of our identity, it is a far better thing than anything we could possibly discover inside of our present selves. I believe this can only be found outside ourselves, in the person of Jesus Christ, the “author and finisher of our faith” (Hebrews 12:2). The scoffers are half-right when they say this is impossible: without the enabling power of Christ, it absolutely would be forever beyond our grasp.

It’s commonly said that Christian sexual ethics warn against Romantic sexuality because it is too free.

Rooted in the timeless, and in the body, it is possible to reclaim what has been lost. One can begin to believe that a mere feeling, no matter how persistent and insistent, does not by itself determine what is real and true and eternal. Carl Trueman laments that human identity has been transformed “into a primarily psychological understanding of personal identity as a state of mind or a state of feelings. What happens if I believe my mind says one thing and my body says another? Expressive individualism would say God got it wrong. But I would ask, what if God got your body right and your mind is what is wrong?”

A friend of mine said to me once, “You do not have a reproductive system. You have half of a reproductive system. It is only in the union of your portion of the reproductive system with someone of a complementary gender’s reproductive system you can fulfill its intended function.” Our very anatomy testifies to us who we are made to be with. Never in all of history has a man with a man, or a woman with a woman, produced offspring. Our anatomy, our biology, is heteronormative. If the Proclamation on the Family is true, and I have a testimony that it is, then eternity is as well. (This does not mean that all mortal conceptions of sex, gender, and sexuality will survive into the resurrection. There is a “mortal overlay” that distorts all of these concepts).

It’s commonly said that Christian sexual ethics warn against Romantic sexuality because it is too free. This is exactly wrong: as argued here, the problem with Romantic sexuality is that it is too confining. And in an echo of how the early Church fell into apostasy when (in a search for intellectual respectability) they grafted Neoplatonism onto revealed Christianity, we are seeing something similar in the larger Christian church, which uneasily and incoherently is attempting to graft these Romantic ideas about identity into traditional Christianity, in an attempt to be more inclusive and welcoming. There may even be some of this impulse among members of the Church of Jesus Christ as well. But that can’t work, as the Christian scholar N.T. Wright explains,

We have lived for too long in a world, and tragically even in a church… where the wills and affections of human beings are regarded as sacrosanct as they stand, where God is required to command what we already love and to promise what we already desire. The implicit religion of many people today is simply to discover who they really are and then try to live it out—which is, as many have discovered, a recipe for chaotic, disjointed, and dysfunctional humanness…

The logic of cross and resurrection, of the new creation which gives shape to all truly Christian living, points in a different direction. And one of the central names for that direction is joy: the joy of relationships healed as well as enhanced, the joy of belonging to the new creation, of finding not what we already had but what God was longing to give us. At the heart of the Christian ethic is humility; at the heart of its parodies, pride. Different roads with different destinations, and the destinations color the character of those who travel by them. (Emphasis added.)

In a lecture on a different occasion, Wright sternly warned against Romantic identity, considering it the ancient heresy of Gnosticism born anew. This philosophy, he writes, “Invites you to search deep inside yourself and discover some exciting things by which you must then live, which declares that the only real moral imperative is that you should then be true to what you find.” Then he went on to caution:

But this is not a religion of redemption. It is not at all a Jewish vision of the covenant God who sets free the helpless slaves. It appeals, on the contrary, to the pride that says “I’m really quite an exciting person, deep down, whatever I may look like outwardly” — the theme of half the cheap movies and novels in today’s world. It appeals to the stimulus of that ever-deeper navel-gazing (“finding out who I really am”) which is the subject of a million self-help books, and the [instigator] of a thousand ethical confusions. It corresponds, in other words, to what a great many people in our world want to believe and want to do, rather than to the hard and bracing challenge of the… gospel of Jesus. [The new Gnosticism] appears to legitimize precisely that sort of religion which a large swathe of America and a fair chunk of Europe yearns for: a free-for-all, do-it-yourself spirituality… and an “I’m OK, you’re OK” attitude on all matters religious and ethical. (Emphasis mine.)

Wright goes on to point out how contrary these ideas are to the original teachings of Jesus, whose challenge to us continues to be “that we should look away from ourselves and… submit to Jesus as Lord and allow all other allegiances, loves and self-discoveries to be realigned in that light.”

These Gnostic ideas affect how Romantics see sexuality. They deride Mimetic, emulative sexuality as constricting, but that is totally wrong. This is no “small and cramped eternity” in G.K. Chesterton’s memorable phrase. Far from being confining, it is expansive—infinitely so: “eternal increase” and “worlds without end.” Far from being restrictive, this view is maximally inclusive, because it encompasses all of creation. Far from being stingy, it is also abundantly generous with a never-ending gifting of glory, as beautifully described in Moses 1:39: “This is my work and my glory—to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man.”

Far from being grim, this expansive view of identity and sexuality is infused with joy and laughter. As Meister Eckhart said, “In the heart of the Trinity the Father laughs and gives birth to the Son. The Son laughs back at the Father and gives birth to the Spirit. The whole Trinity laughs and gives birth to us.” Though I disagree with the Trinitarian theology in this passage, I wholeheartedly embrace its impulse, the pairing of joy and laughter with the powers of creation.

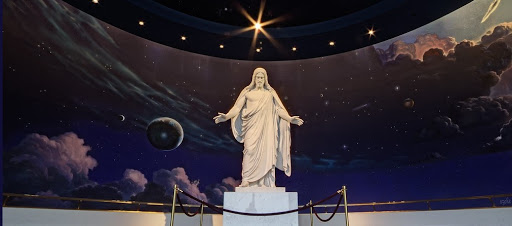

Mural behind Christus Statue replica, in Salt Lake Temple Square Visitor’s Center.

Compared to the infinite canvas and the multitudes of creative expression this can create (literally innumerable to our mortal minds), the Romantic view of sexuality is limited, constricting, enslaving, exhausting, and ultimately pointless. It cannot see past its own subjective experience. Instead of the ever-expanding creation, Romantic sexuality is contractive—it only welcomes, at most, one other person but only in his or her capacity to induce (momentary) satisfaction; its raptures are hoarded and confined to the participants, with no enduring life.

Yearning for Renewal

What we most yearn for is not self-knowledge, but renewal. We certainly need it! Six verses out of Eden, Adam and Eve experience the unimaginable pain of having one son murder another. Every other family, in ways large and small, has also fallen short of the divinely revealed family ideal. All families, including the first family, have been dysfunctional.

The beauty and wonder are that Christ has the power not just to heal but to make things better than before. C.S. Lewis put it this way:

For God is not merely mending, not simply restoring a status quo. Redeemed humanity is to be something more glorious than unfallen humanity would have been, more glorious than any unfallen race now is…. And this super-added glory will, with true vicariousness, exalt all creatures.

The Grand Staircase in the Rome Italy Temple.

This is what Latter-day Saints are doing in our temples! We aren’t baptizing dead people in order to swell our membership rolls out of some misplaced (and colossally expensive) sense of inadequacy. No, from the bottom of the baptismal font to the top of the sealing room, the work in our temples is a work of repair and restoration. It is, first, putting the fractured human family back together: husband reconciled to wife, child reconciled to parent, one family at a time, all the way back to Adam and Eve. These repaired relationships are extravagantly laden with the literally infinite blessings of Abraham. There is also the sweet promise that these relationships will endure throughout the eternities. And it is the healing and sealing power of the atonement of Jesus Christ that infuses every ordinance and makes it all work.

Like our first parents, we feel our own great pain when our family experience falls short of the ideal—if we have one at all. For a variety of reasons, we may even lack the opportunity, the desire, or feel unable to participate in a divinely appointed marriage. Such a possibility may seem very far off indeed. We may decide this tells us something about our identity. We may go beyond Moses and feel that not merely mankind, but our own self, is nothing. Our deepest desires and longings may seem out of harmony with what we have been taught is the divine design for our destiny. Those feelings may have been with us for as long as we can remember, so it is easy to conclude they will last through this life and maybe even into the next. In such a circumstance, we may either decide we are some kind of mistake, or that the revealed plan is.

But Elder Tad Callister says: “If one does not correctly understand his divine identity, then he will never correctly understand his divine destiny. They are, in truth, inseparable partners.” So it should not be surprising if some of those who have substituted a Romantic identity for a Mimetic one might also feel discomfort with, or even reject, their divine destiny.

Elder Scott Whiting recently added, “You are good enough, you are loved, but that does not mean that you are yet complete. There is work to be done in this life and the next. Only with His divine help can we all progress toward becoming like Him.”

Some Practical Suggestions

In this article, I have at times been sharp in my criticism of certain ideas. I plead with you not to mistake my criticism of these ideas with criticism of the people impacted by them. I am more aware than most of the profound pain, loneliness, alienation, and suffering of people who feel their deepest nature is profoundly at odds with a religious-based identity I have presented here. I have devoted a significant portion of my time, talents, and money to hopefully be a more effective minister to people like this. I know that my ministry and my love have been imperfect. But because of my own background and that of people close to me, I have profound compassion and respect for all who are affected by these issues.

We should seek for change, but a very special kind of change.

For those who think they might be able to help those under the sway of Romantic identity, I plead with you to be compassionate and loving. Their hearts are unlikely to be changed by argumentation or reasoning alone, if at all. So there is no reason to, for example, forward this article along to them. My message is rather aimed at those in the middle, who may sense an unease or tension between these competing concepts of identity but may not know why. Our best approach in countering these popular, prevailing notions is to sketch out as vividly as possible the beauty and promise of our vision of human completeness. Let our intellectual opponents do the same for theirs, and then let people choose which one they find more compelling. I wonder if this is what Joseph Smith meant when he said, “by proving contraries, the truth is made manifest.”

For those of us who want to walk the covenant path, but it somehow feels impossible or incongruent with our identity, what can we do? We should seek for change, but a very special kind of change. In Wendy Watson Nelson’s 1998 devotional address “Change: It’s Always a Possibility!” She tells the story of a caterpillar named Yellow who wanted to know what a butterfly was:

When she heard the word butterfly, her whole insides leapt. “But what is a butterfly?”

The cocooned caterpillar explained: “It’s what you are meant to become.” Yellow was intrigued but a bit defiant. “How can I believe there’s a butterfly inside you or me when all I see is a fuzzy worm?” On further reflection, she pensively asked, “How does one become a butterfly?” And the answer? “You must want to fly so much that you are willing to give up being a caterpillar.”

Much more could be said about how this kind of change may be brought about (as Sister Wendy Nelson herself does), but that is beyond the scope of this article. It does help to understand what may change, and what may not change, at least for now. Sometimes I have found that my focus on what I so badly wanted to change blinded me to other, possibly greater opportunities for change that God is trying to offer me first.

If you resonate with the ideas I’ve presented here, don’t be surprised if your feelings are not widely shared. You are in the minority. This is not the way the world sees things anymore. Some may not even be capable of understanding Mimetic identity; they’ll try to fit it into the Romantic box and assume it is just another inward-directed quest for a deeper, more authentic self. Others will consider it hateful and excluding. Even among fellow believers, you may find espousing these ideas invites a frosty reception or awkward silences in certain quarters.

Countenances Shining with the Love of Jesus

The Rome Italy Temple Visitor’s Center.

All of us have things we must surrender and change in order to dwell in everlasting burnings. In C. S. Lewis’s The Great Divorce, a guide takes our protagonist to a sort of heavenly anteroom where spirits from a higher realm come to persuade those from the lower realm to let go of their damning beliefs and behaviors in order to partake of a greater fullness. (This is close to how I imagine missionary work operating in the Spirit World). The narrator asks his guide what parts of ourselves can ascend to heaven (i.e., be resurrected):

Nothing, not even the best and noblest, can go on as it now is. Nothing, not even what is lowest and most bestial, will not be raised again if it submits to death. It is sown a natural body, it is raised a spiritual body. [Mortal] flesh and blood cannot come to [Heaven]. Not because they are too rank, but because they are too weak… Lust is a poor, weak, whimpering, whispering thing compared with that richness and energy of desire which will arise when lust has been killed… Ye must ask, if the risen body even of appetite is as grand… as ye saw, what would the risen body of maternal love or friendship be?

If we are willing to renounce the poisoned chalice of divisive intersectional group identity, we can accept Paul’s invitation to “come in the unity of faith, and of the knowledge of the Son of God, unto a perfect man, unto the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ.” Instead of the disunity intrinsic in measuring our oppression against another’s, may we all unitedly measure ourselves against the perfection and fullness of our Redeemer. Any victory in intersectionality’s oppression Olympics is tentative and temporary, whereas the perfect victory Christ offers is attainable, even in this life.

The prophets Mormon and John promise us that if we attain perfect love, we will recognize Him because we will have become like Him. Alma said that with a pure heart and clean hands we can engrave Christ’s image into our countenances. This is fitting since we are already engraven upon His palms.

John affirms our divine identity as sons [and daughters] of God, but warns that “it doth not yet appear what we shall be.” This is Mimetic identity: what we are is what we will be, but are not yet (paradoxical as that sounds). And we will recognize it when we see it: “[W]e know that, when he shall appear, we shall be like him; for we shall see him as he is.”

After amplifying this same teaching, Mormon gives us the key to attaining this Christlike identity, and that is love. We must “pray unto the father with all the energy of heart, that ye may be filled with this love.” (Emphasis added.)

Terryl Givens asks and answers:

But how to develop the kind of love that we seek? The love that has fired the hearts of Christ’s most fervent and reliable disciples is not easily acquired. That is why Moroni urges us that we must “pray with all the energy of our souls” to obtain it; why, as President Benson urged, we must “make faithfulness to His counsel a quest”; why, as King Benjamin observed, we cannot “know the master we have not served”; why, as Alma counseled his son, we must learn to “place all the affections of the heart upon Him”; finally, it is why, as the great Cambridge Platonist John Smith wrote, “That which enables us to know and understand aright the things of God must be a living principle of holiness within us.’”

T.S. Eliot said the end of all our exploring would be to arrive at where we started. That may be the end of exploration, but it is not the end of his poem. This is how it ends:

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flames are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.

We yearn for belonging, to see as we are seen and to know as we are known. We yearn for love, but not the cheap and temporary kind the world sings about on the radio. We yearn for the kind of love that will never fail, that is more reliable than prophecy, tongues, and even knowledge itself. We pray for that kind of love that only God can give us and that only through the enabling power of Christ we can give to others. The rest is just endless wandering. As Augustine prayed, “Thou hast made us for thyself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it finds its rest in thee.”

We also know that not all of our desires can and will be realized in this life. Here, too, our Savior is a pattern. What would His life and ministry mean without the resurrection? If His story stopped at His death on the cross, how much would be missing!

Much of our story will also unfold after mortality. Victor Hugo wrote,

The nearer I approach the end, the plainer I hear around me the immortal symphonies of the worlds which invite me. . . . For half a century I have been writing my thoughts in prose and verse; history. . . . I have tried all. But I feel I have not said a thousandth part of what is in me. When I go down to the grave, I can say, like so many others, “I have finished my day’s work,” but I can not say, “I have finished my life.” My day’s work will begin again the next morning. The tomb is not a blind alley; it is a thoroughfare. . . . My work is only beginning. (Emphasis added.)

Some Closing Thoughts

Or as Joseph Smith put it, “All your losses will be made up in the resurrection. By a vision of the Almighty I have seen it!”

We might need to elevate our vision. We might be selling ourselves short and living below our privileges. However unreachable it may feel, Elder Whiting proposes, “The Savior’s admonition to be ‘even as I am’ is far from hyperbole or figurative—even in our mortal condition.” Suggesting that’s “precisely what is meant” by the Lord’s words, he asks, “What level of effort are we willing to give to invite His presence into our lives so that we can change our very nature?”

May we all have this vision! Not just of our losses restored to us, but all that we will be in the resurrection. May we write His name in our hearts, may we pray with all the energy of heart to be filled with His love. May we find His image not only in our own countenances, but in the hungry, the thirsty, the stranger (or immigrant), the naked, the sick, and the imprisoned. The glory of ourselves in that future day is unimaginable, though I have seen glimpses of it: what we can be but are not yet. I pray you will be able to see that for yourself as well.

The post Whose Image Are You Seeking In Your Countenance? appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →