The Know

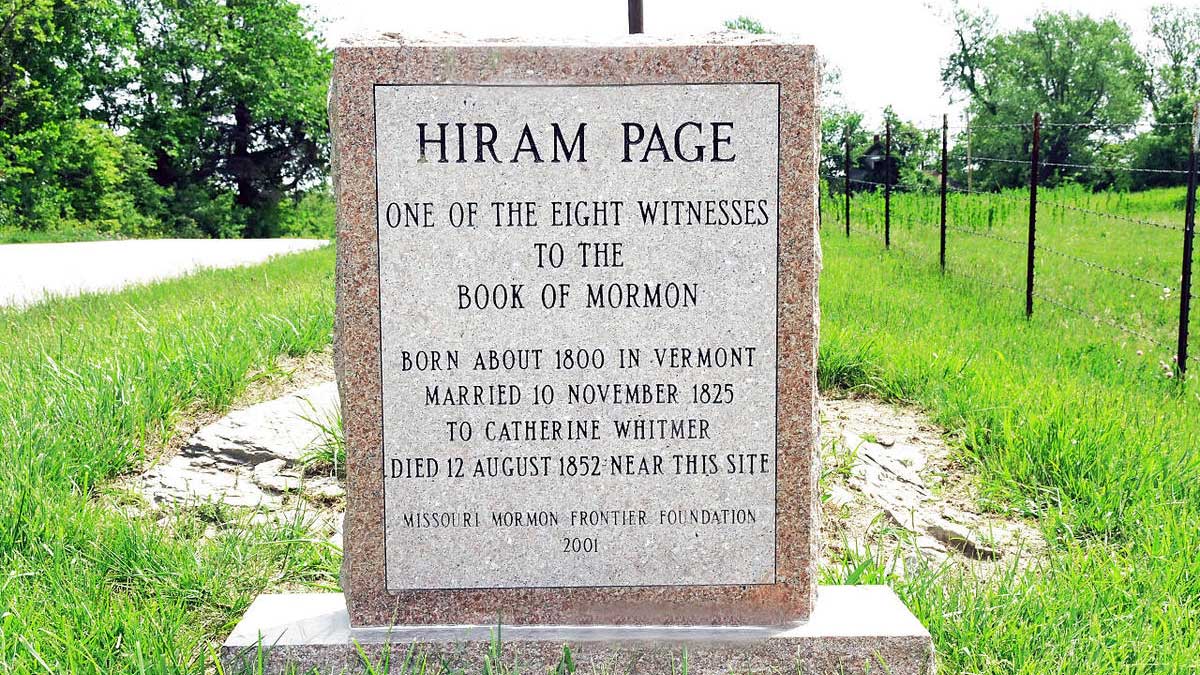

At the beginning of the Book of Mormon, a statement approved by eight named witnesses declares that Joseph Smith “has shown unto us the plates … which have the appearance of gold; and as many of the leaves as the said Smith has translated we did handle with our hands.” They added that they “also saw the engravings thereon, all of which has the appearance of ancient work, and of curious workmanship.”1 Among these eight, the name Hiram Page stands out as the only one who was not named Whitmer or Smith. Nonetheless, he is among the lesser-known witnesses today.

Despite not being named Whitmer, Page was, in fact, part of the Whitmer clan. In 1825, he had married Catherine Whitmer––daughter of Peter and Mary Whitmer.2 They lived near Catherine’s parents farm when Joseph and Oliver were there translating the Book of Mormon and thus became acquainted with the work. In June 1829, as Joseph completed the translation, he selected Page to be among the Eight Witnesses.3

Later, as the Book of Mormon was being printed early in the winter of 1830, Page was commissioned by revelation to travel with two others to Canada to try to secure the copyright there and throughout the British Empire by printing and selling the Book of Mormon.4 Page obediently joined Oliver Cowdery and perhaps others on the trip, the prophesied success of which was dependent upon “if the people harden not their hearts against the enticing of my spirit and my word.”5

Unfortunately, they failed to obtain a copyright to Book of Mormon. Later in life, Page’s brother-in-law and fellow Book of Mormon witness, David Whitmer, expressed cynicism toward this seemingly failed revelation, but Page did not. Instead, Page remembered the conditional nature of the revelation, and felt it was a learning experience on “how a revelation may be received and the person receiving it not be benefitted.”6

In addition, perhaps the best-known event involving Page was his role in the circumstances leading to the revelation now known as Doctrine and Covenants 28. In September 1830, Page obtained a seer stone and began receiving what he believed were revelations concerning the establishment of Zion and matters of church order and hierarchy which many believed including the Whitmers and Oliver Cowdery.

When Joseph learned about the purported revelations, however, he was alarmed; and he sought the Lord directly to know what he should do. The Lord revealed that “those things which [Hiram Page] hath written from that stone are not of me and...Satan deceiveth him” (D&C 28:11). The Lord further instructed Joseph and Oliver in the proper order of revelation in the Church and counseled Oliver to correct Page privately.7 To his credit, Page responded with “loyalty and faith toward Church leaders” and had his seer stone destroyed.8

For the next several years after this incident, Page faithfully followed his Church leaders. Page answered the call to gather in Ohio. When the true location of Zion was revealed to be Independence, Missouri, Page relocated there to help establish Zion.9 Like many other Latter-day Saints who settled in Missouri in the 1830s, Page endured intense persecution. In 1833, accounts indicate that he was attacked and beaten by a mob which intended to kill him.10 Eventually, one of the leaders of the mob proposed, “If you will deny that damned book [of Mormon], we will let you go.” Page responded, “[h]ow can I deny what I know to be true?”11 The beating continued until they realized he would not revoke his testimony, so they let him go.

As Page’s brothers-in-law Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and John Whitmer became disaffected from the Church in 1838, Page also “lost confidence in Joseph Smith and withdrew from the Church.”12 Like all of the Book of Mormon witnesses, however, Page remained faithful to his testimony of the Book of Mormon despite facing economic hardships during his years out of the Church.13 In a letter to former apostle William E. McLellin, who had also become disillusioned with Joseph Smith, Page insisted “[a]s to the book of Mormon, it would be doing injustice to myself, and to the work of God of the last days, to say…that my mind was so treacherous that I had forgotten what I saw.”14

Page passed away a few years later, in August 1852, still relatively young in his early 50s.15 Those who knew him insisted that he was true to his testimony of the Book of Mormon throughout his life. For example, John C. Whitmer, Page’s nephew, said, “I knew him to at all times and under all circumstances to be true to his testimony concerning the divinity of the Book of Mormon.”16 His son, Philander Page, likewise reported:

I knew my father to be true and faithful to his testimony of the divinity of the Book of Mormon until the very last. Whenever he had an opportunity to bear his testimony to this effect, he would always do so, and seemed to rejoice exceedingly in having been privileged to see the plates and thus become one of the Eight Witnesses.17

The Why

In the early months after the Church was first organized in April 1830, the Saints were still learning, line upon line, about the divine order of God’s kingdom here on earth. As such, misunderstandings—such as the incident with Hiram Page’s seer stone—were bound to arise during this early period. Page’s mistake gave Joseph Smith the opportunity to seek important, clarifying revelation that helped the fledging Church better understand that “all things must be done in order, and by common consent in the church” (D&C 28:13), and that revelation for the whole Church could only come through those appointed to the head of the Church (D&C 28:6, 12). Hiram Page was teachable, and this trait blessed him throughout his life.

This incident also makes it evident, that while the Lord can work through instruments like seer stones, this does not mean that all activities and perceived revelations involving a seer stone are approved of the Lord. Satan, too, can imitate the Lord’s revelations through these means (D&C 28:11). For Latter-day Saints today, this episode provides an important reminder that when seeking personal revelation, one must always do so with their proper stewardship in perspective, and not seek revelation that goes beyond their place. Page learned to be sensitive to correct principles and proper leadership.

Furthermore, Page, as all people should be, learned to be cautious of so-called “personal revelation” that runs against the grain of teachings by the current prophets, seers, and revelators leading the Lord’s Church today. The Lord’s council to Oliver Cowdery and Hiram Page, that there shall be nothing “appointed unto any of this church contrary to the church covenants” (D&C 28:12) is just as true now as it was in 1830.

This early misunderstanding is not all that Page should be remembered for, however. He quickly learned his lesson, humbled himself, and repented. Because of that, Hiram Page made important contributions to the Restoration that may not always be as visible and noticeable as those of others. For example, the fact that Page was included among the Book of Mormon witnesses indicates that he was among those who had “assist[ed] to bring forth this work” during the translation process (Ether 5:2). Even though the specific ways he had helped are not clearly documented in the historical record, his spirit of meekness made his testimony of the Book of Mormon that much more unshakeable.

After the translation was complete, as previously mentioned, Page sought to assist in bringing the work forth by traveling to Ontario, Canada with Oliver Cowdery to secure the Canadian copyright of the Book of Mormon. Although they did not succeed, the revelation that had been given made it clear to him that this was through no fault of their own, but rather because the people of Canada were not prepared at this time. He did not jump to a false conclusion by trying to find fault with Joseph or with the revelation.

Hiram Page also faithfully sought to build up Zion for several years, after its true location was revealed through the proper channels of revelation. Like many others, he suffered severe persecution for following the Lord’s directions, but he had seen the Book of Mormon plates, and he could not deny them. Even as he lost faith in other aspects of Joseph Smith’s prophetic calling, he remained true to what he saw and testified of in 1829. As Richard Lloyd Anderson observed, “[c]onflict with religious associates and the fight for economic survival breaks the idealism of many a man, but Hiram Page’s enthusiasm for the Book of Mormon was strong in adverse circumstances.”18

Whenever Page had the opportunity, he gladly bore his testimony of the Book of Mormon, which all the more helped him to endure to the end. Those who cherish the Book of Mormon’s witness of Christ today should likewise value and appreciate Hiram Page’s faithful testimony borne throughout his life.

Further Reading

Susan Easton Black, “Hiram Page (1800–1852),” in Restoration Voices Volume 1: People of the Doctrine and Covenants (Springville, UT: Book of Mormon Central, 2020).

Bruce G. Stewart, “Page, Hiram,” in Doctrine and Covenants Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey and Larry E. Dahl (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2012), 472–473.

Richard L. Anderson, “Personal Writings of the Book of Mormon Witnesses,” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 52–53.

- 1. The Testimony of Eight Witnesses.

- 2. See Susan Easton Black, “Hiram Page (1800–1852),” in Restoration Voices Volume 1: People of the Doctrine and Covenants (Springville, UT: Book of Mormon Central, 2020).

- 3. Scholars agree that the Eight Witnesses likely saw the plates sometime in late June or early July 1829. John W. Welch, “The Miraculous Timing of the Translation of the Book of Mormon,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestations, 2nd edition, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Studies, 2017), 125 suggests the Eight Witnesses saw the plates around June 29, 1830. Patrick A. Bishop, Day After Day: The Translation of the Book of Mormon, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2018), 102 proposes the next day, June 30, 1829. Gale Yancey Anderson, “Eleven Witnesses Behold the Plates,” Journal of Mormon History 38, no. 2 (2012): 152–156 argues it was July 2, 1829.

- 4. For more details on this incident, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Joseph Smith Attempt to Secure the Book of Mormon Copyright in Canada?” KnoWhy 556 (April 7, 2020). The definitive treatment on this is Stephen K. Ehat, “‘Securing’ the Prophet’s Copyright in the Book of Mormon: Historical and Legal Context for the So-called Canadian Copyright Revelation,” BYU Studies 50, no. 2 (2011): 5–70.

- 5. Revelation, circa Early 1830, 31, online at josephsmithpapers.org.

- 6. Letter to William McLellin, February 2, 1848, in Dan Vogel, ed., Early Mormon Documents, 5 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 1996–2003), 5:258–259.

- 7. For additional background and commentary on this revelation, see Stephen C. Harper, “Section 28,” in Doctrine and Covenants Contexts (Springville, UT: Book of Mormon Central, 2021), 58–59.

- 8. Bruce G. Stewart, “Page, Hiram,” in Doctrine and Covenants Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey and Larry E. Dahl (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2012), 473.

- 9. See Stewart, “Page, Hiram,” 473; Black, “Hiram Page (1800–1852).”

- 10. Don Carlos Smith, Journal, September 30, 1838, extracted in Joseph Smith, History, 1838–1856, vol. C-1 Addenda, p. 13, online at josephsmithpapers.org. See also Mitchell K. Schaefer, ed., William E. McLellin’s Lost Manuscript (Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2012), 167.

- 11. Schaefer, William E. McLellin’s Lost Manuscript, 167, capitalization silently altered.

- 12. Stewart, “Page, Hiram,” 473.

- 13. See Richard Lloyd Anderson, Investigating the Book of Mormon Witnesses (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1981), 129.

- 14. Hiram Page to William E. McLellin, May 30, 1847, in Larry E. Morris, ed., A Documentary History of the Book of Mormon (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019), 428. See also Richard L. Anderson, “Personal Writings of the Book of Mormon Witnesses,” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 52–53.

- 15. Stewart, “Page, Hiram,” 472.

- 16. Andrew Jenson, Edward Stevenson, and Joseph S. Black, Report of an Interview with John C. Whitmer, September 12, 1888, in Morris, Documentary History, 445.

- 17. Andrew Jenson, Edward Stevenson, and Joseph S. Black, Report of an Interview with Philander Page, September 1888, in Morris, Documentary History, 446.

- 18. Anderson, Investigating, 129.

Continue reading at the original source →