I just began reading the latest book on the Book of Abraham, Dan Vogel's Book of Abraham Apologetics: A Review and Critique (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 2021). After reading his claim to just be pursuing history "based entirely in a dispassionate, balanced analysis of the relevant historical documents" (p. 13, Kindle edition), I was expecting what would at least appear to be a cautious approach, carefully weighing evidence and not overlooking sources and arguments that weigh against Vogel's well-known critical views of Joseph Smith. Unfortunately, disappointment followed swiftly in several ways, especially when he relies on the ignorance of Joseph and his peers regarding the significance of the famed achievement of Champollion in translating the Rosetta Stone. This alleged ignorance advances Vogel's thesis in two ways: 1) it gives Joseph the courage to do his own translation, believing that there is no risk (at least for his near future) of scholars later exposing his bogus translation, and 2) it allows him to cling to the once popular old notion that Egyptian was a mystical language where one character could require numerous words to translate.

At the core of many modern attacks on the Book of Abraham is the notion that a handful of Egyptian characters in the margins of some Book of Abraham manuscripts written by Joseph's scribes represent the translation work of Joseph Smith. If so, then Joseph apparently thought that a single character could represent complex story details that require as many as 200+ English words to translate. This would seem to require Joseph to have been ignorant of Champollion's famous translation of the Rosetta Stone, where Egyptian symbols (hieroglyphs and demotic script) were not mysteriously linked to large blocks of Greek text, but were found to have a much more reasonable relationship.

While Champollion's achievement is common knowledge now, many people today fail to recognize how significant and well known his achievement was in the 1820s and 1830s. Vogel also makes this oversight early in his book:

At the time Smith worked on his “Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language,” [Vogel repeatedly asserts that the GAEL was Joseph's work, which requires overlooking a great deal of evidence that we will discuss later] he does not appear to be aware of the significance of François Champollion’s contribution to Egyptology, as was the case for most Americans. When Champollion died in 1832, his work on the Rosetta Stone was incomplete and his “decipherment remained a speculative hypothesis to many scholars.” [Here the book is missing a footnote to Parkinson's Cracking Codes, p. 41.] As late as 1854, orientalist Gustavus Seyffarth was still arguing in New York against Champollion’s system. Not until 1858 would a complete translation of the Rosetta Stone come off an American press. LDS scholar Samuel Brown has noted that “Champollion’s phonetic Egyptian was slow to find traction because hieroglyphs had so long been understood to function as secret pictographic codes,” and historian John Irwin has observed that “Champollion’s discoveries did not, however, topple the metaphysical school of interpretation … and the tension between these two kinds of interpretation was to have a significant influence on the literature of the American Renaissance.” After reviewing this subject, Terryl Givens, another LDS intellectual, recently suggested that “Smith or those working to assemble the grammar and alphabet appear to have been operating within the existing cultural assumptions of the time about how hieroglyphs concisely embedded substantial discursive meaning.”

This gave Smith freedom to imagine whatever he wished about Egyptian grammar. His Egyptian-language project began as a relatively simple alphabet and the five-degree amplification of Egyptian meanings came later, which helps to explain evolving definitions. It also provided more flexibility when he later dictated his translation. (pp. 25-26 in Kindle, pp. 6-7 in print)

First, I must object to Vogel's insistence from the beginning that the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language was Joseph's work. This popular theory is challenged by extensive data that we will discuss later, but for now please see two recent publications by John Gee that provide incisive analysis on this and related issues: "Fantasy and Reality in the Translation of the Book of Abraham," Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 42 (2021): 127-170, and "Prolegomena to a Study of the Egyptian Alphabet Documents in the Joseph Smith Papers," Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 42 (2021): 77-98.

Getting back to Champollion, I believe that Vogel misses the significance of Irwin's opening chapter about how widespread knowledge of Champollion had become in the US shortly after his translation, even if those favoring metaphysics misinterpreted his work. The fact that several scholars remained fascinated with the potential metaphysical aspect of hieroglyphics after Champollion's translation does not mean that Champollion's achievement was not well known, nor that the frequently phonetic nature of hieroglyphs was not known in America. There are numerous sources from the United States prior to Joseph's work with the papyri showing that Champollion was a household name and that his decipherment of the Rosetta Stone was well known. I provide some of these sources in "A Precious Resource with Some Gaps," Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 33 (2019): 13-104, which Vogel cites in his book. That source also points out that Joseph's Book of Mormon translation gives us important clues about what he thought about Egyptian or reformed Egyptian, factors that Vogel also seems to have overlooked.

Yes, mystical views of Egyptian may have lingered in the U.S. (and W.W. Phelps may have entertained related notions pertaining to the ideal "pure language"), but it is not reasonable to make the assumption that Joseph and the early Saints remained largely ignorant of Champollion's work and its general significance. For example, consider this from The Atlantic magazine in 1825: "The learned are well acquainted with the important discoveries of Young and Champollion in decyphering the sacred writings of the Egyptians" ("Discovery of Very Ancient Egyptian Archives," vol. 2, p. 399). The Atlantic in 1825 tells us that the learned are well acquainted with Champollion, whose name was so well known that it needed no title, no initials or hint of a given name. In the 1820s in the US he was already simply Champollion.

I suspect that the notion of some critics of the Book of Abraham that Champollion's work was not common knowledge in the U.S. by 1835 may derive from a blunder of Dr. Robert K. Ritner, a critic of Joseph Smith and the Book of Abraham who is widely relied on by Book of Abraham critics. I discuss Ritner's error in my post, "The Making of a Myth: A Possible Explanation for the Mysterious Ignorance of Champollion (Among Scholars)." Ritner is not only heavily cited by critics of the Book of Abraham, but also by the editors of the Joseph Smith Papers' volume on the Book of Abraham, Brian Hauglid and Robin Jensen, who cite him more than any other scholar (while never citing Hugh Nibley). They appear to follow Ritner when they claim that "in America in the 1830s and 1840s, Champollion’s findings were available to only a small group of scholars who either read them in French or gleaned them from a limited number of English translations or summaries" (The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts, eds. Robin Scott Jensen and Brian M. Hauglid [Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2018], p. xvii). While the academic details of Champollion's academic publications were not common knowledge in the U.S., of course, downplaying the widespread awareness of Champollion's achievement and its significance is simply unjustified.

In fact, there is some evidence that the early Saints likely were aware of Champollion. See my recent post, "Is There Direct Evidence that the Early Saints Had Heard of Champollion?" There I point to a widely published article by journalist James Gordon Bennett claiming that when Martin Harris took a copy of some Book of Mormon characters to seek assistance from scholars, Dr. Samuel Mitchill told Martin that the characters resembled those that Champollion had found. Even if Martin had not been told anything about Champollion by Mitchill, the article would surely have stirred curiosity if the Saints were still in the dark.

Regardless of what Joseph knew of Champollion, we can infer more on Joseph’s views by assuming that what he had published in and said about the Book of Mormon regarding reformed Egyptian should not depart wildly from his personal views. For example, Mormon in Mormon 9:32 tells us that

we have written this record according to our knowledge, in the characters which are called among us the reformed Egyptian, being handed down and altered by us, according to our manner of speech.

The reformed Egyptian of the Book of Mormon apparently reflected speech rather than having a single character mystically conveying vast treasures of oracular thought.

Mormon’s statement is not the only vital clue on the nature of Egyptian. King Benjamin in Mosiah 1:4 explains that Lehi taught the language of the Egyptians to his children so they could read the brass plates, and so they could teach that to their children in turn. The implication, of course, is that Egyptian is a language you can teach to your children, one that does not require mystic gifts to draw out mountains of hidden text from a few strokes.

Apart from indications in the Book of Mormon about the nature of the Egyptian on the brass plates and the reformed Egyptian used by Mormon, Joseph Smith also expressed his viewpoint directly. Regarding the title page of the Book of Mormon, which came from the last plate (not the last character!) in the Nephite record, Joseph said:

I would mention here also in order to correct a misunderstanding, which has gone abroad concerning the title page of the Book of Mormon, that it is not a composition of mine or of any other man’s who has lived or does live in this generation, but that it is a literal translation taken from the last leaf of the plates, on the left hand side of the collection of plates, the language running same as all Hebrew writing in general. [Joseph Smith, “History, circa June–October 1839 (Draft 1),” p. 9, Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-circa-june-october-1839-draft-1/9.

It was a running language, with a chunk of language on the last plate corresponding to the chunk of English on our title page, not an utterly mystical language, one where each squiggle could be paragraphs of English. With his experience in reformed Egyptian behind him, does it stand to reason that once he saw the Egyptian scrolls in 1835, he would suddenly reverse course and see it as pure mysticism completely unlike Hebrew, no longer phonetic nor a “running language”?

Further evidence against such a view comes from Joseph’s comments on the meaning of the Facsimiles. The four hieroglyphs for the four sons of Horus in Facsimile 2 (labeled as element 6) become a remarkably concise “the four quarters of the earth,” a statement that is actually quite accurate. Other statements he makes regarding the facsimiles and the characters tend to be equally brief. No sign of magical compactness. That idea died swiftly, though not universally, as news of the translation of the Rosetta Stone spread. It was old news when Joseph saw the scrolls. While it is possible that Joseph and the people of Kirtland had remained in the dark about the Rosetta Stone and Champollion, it seems unlikely. But certainly there was still nothing practical available from Champollion’s work in that day to guide them, even if they had had access to French publications. For that, revelation would be needed, and it seems they then would do their best on their own to follow suit and create their own “Alphabet.” But the revealed translation came first. Indeed, from the very beginning we have Joseph identifying some of the records as having texts about Abraham and also Joseph. This came not by painstakingly creating an impossible "alphabet" out of nothing to identify those names, but came by revelation.

W.W. Phelps, based on his writings in the GAEL, may have continued to entertain the notion that Egyptian characters could have many levels of meaning and might convey a sentence or phrase when translated. But we have no reasonable basis to assign that belief to Joseph.

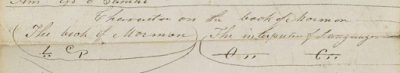

If one's goal is to pursue history "based entirely in a dispassionate, balanced analysis of the relevant historical documents," there are a couple more relevant documents that should be considered but apparently are not discussed (at least not yet in my reading) in Vogel's book. There is a document from Oliver Cowdery which gives us some insight into the "comprehensive" nature of the Egyptian language that Cowdery once spoke of. The document is listed on the Joseph Smith Papers website as "Appendix 2, Document 2a. Characters Copied by Oliver Cowdery, circa 1835–1836." The document, apparently in the handwriting of Oliver Cowdery, gives a few words of English, a transliteration of the purported Hebrew translation, and then shows two pairs of Egyptian-like characters beneath a pair of English phrases: "(The Book of Mormon)" and "(the interpreters of languages)."

|

| Cowdery equates a four characters of reformed Egyptian to eight words of English (four of which are "the" and "of") |

There are two characters for "the Book of Mormon" and two for "the interpreters of languages." Sure, it's compact and concise -- but not ridiculously and impossibly so. And frankly, in my uneducated opinion, those presumably reformed Egyptian characters could easily fit in with the Egyptian script on the Joseph Smith Papyri, another version of reformed Egyptian. "Reformed Egyptian," of course, is not a specific name of a language -- "reformed" is just an adjective describing the evolution and revision that had occurred in the Nephites' Egyptian script for sacred records, just as real Egyptian had variants that evolved into forms of hieratic or demotic. Consider also the document from Frederick G. Williams, listed on the JSP website as "Appendix 2, Document 2b. Writings and Characters Copied by Frederick G. Williams, circa Early to Mid-1830s." It apparently copies part of Cowdery's document, and was written by 1837 or earlier. These men, at least for a while, had a relatively reasonable view about what language could do. Whatever Phelps, Williams, and Warren Parrish thought they were doing when the placed one character to the left of some large chunks of Book of Abraham English text that Joseph had already translated, it simply makes no sense that they and Joseph had lost all sense of proportion and had forgotten what they should have learned from the Book of Mormon and from Joseph's statements, if not their own.

[The following paragraph is an update from April 3, 2021.]

On the other hand, there is a document listed on the Joseph Smith Papers site as "'Valuable Discovery,' circa Early July 1835," where Cowdery places some Egyptian characters in line with an apparent English translation. It begins with several characters and a reasonable block of text, then several more and short block of text, and then follows what looks like just one character followed by 26 words of text, not unlike many of the definitions in the GAEL. So yes, as with the GAEL and most extremely with the Book of Abraham Manuscripts, there were obviously some efforts made to connect individual characters with text. Here we don't know how the text came about--was there a translation first in search of characters to match? The English text is also given in a similar manuscript, "Notebook of Copied Characters, circa Early July 1835" by W.W. Phelps, which Phelps initially wrote was a translation of the characters on the next page. If that were all we had, we would see about 45 English words linked to 37 characters, but latter Phelps, using a graphite pencil, would add the faint phrase "in part" to the side of "translation," suggesting that the translation was only a partial translation. That would be consistent with what we see on the "Valuable Discovery" document, and may have be written in light of what he saw there, where perhaps just 7 characters gave the 45 English words, indicating that there must be more. So do we have what initially Phelps felt was a translation of the characters, which he later felt was only a partial translation after seeing Cowdery's document? It's hard to say, but again, the GAEL likewise shows single characters with surprisingly long English text.

I don't know what Phelps thought he was doing in the GAEL or what any of the Saints thought they were doing in the puzzling documents of the Kirtland Egyptian Papers, but work that was done using an existing translation (and other existing sources like portions of the Doctrine and Covenants) and then quickly abandoned in a totally incomplete state simply does not reflect how Joseph translated the Book of Abraham or the Book of Mormon or any other document. Further, the strangeness of efforts to link single characters to over 200 English words (taken from existing text) in some cases in the Book of Abraham manuscripts should not readily outweigh what we learn from Joseph's views in his work with reformed Egyptian characters in the Book of Mormon.

As Ryan Larsen once pointed out to me, Joseph did not translate the Book of Mormon, the Book of Moses, Section 7 of the Doctrine and Covenants, or any other document by writing characters in one column and text in another, after first trying to fabricate an "alphabet" out of nothing. Alphabets, of course, require some already translated text to create to help one begin to understand a language. Those who witnessed Joseph translate give zero support for the claims of critics regarding how Joseph translated the Book of Abraham. Joseph translated by revelation, not by studying characters and making countless guesses on each one's meaning.

|

| Frederick G. Williams copied the characters and translation from Cowdery |

At least some of the documents I've discussed in related posts and articles, a few of which are mentioned here, are ones that I think Dan has at least briefly seen due to his responses to some of my posts here and articles at Interpreter, which adds to my disappointment of the neglect of the arguments and documents I've mentioned.

I'm only a few pages into Vogel's book, but already I am not convinced that this work really is a dispassionate consideration of the relevant documents, unless relevant means "documents that support one's point of view." But of course, how can one suddenly become dispassionate about something one is already quite passionate about? That passion, of course, can sometimes lead even the best of scholars to overlook conflicting views and evidence.

Related resources:

- "Egyptomania and Ohio: Thoughts on a Lecture from Terryl Givens and a Questionable Statement in the Joseph Smith Papers, Vol. 4"

- "What did Joseph Smith say about the nature of Egyptian hieroglyphs?," from the I Began to Reflect blog

- Pearl of Great Price Central (pearlofgreatpricecentral.org)

Continue reading at the original source →