For about twelve years I worked information security for a few different software companies. We sold our software to companies and government agencies concerned with making sure those accessing their sensitive systems were (a) who they said they were, and (b) only accessing information they should have access to. The first concern is called authentication (“are you who you say you are?”), and the second one is called access control (“do you have access to the information that you need and are you denied access to the information you shouldn’t have?”). Solving these two problems have always been a challenge. And though their implementation has changed throughout time, the solutions are basically the same.

While the temple has ancient roots, it contains features that are used in the most modern and secure computer systems.

It was only a few days after I’d completed a computer security certification when I went through an endowment session again. It occurred to me that you could look at the endowment though an information security lens and gain some valuable insights. I’ll explore some of them in this post. Some of my discussion will necessarily be oblique, and may only make sense to those who have been through themselves. I take seriously the desire to keep these things sacred, and I hope my post here will be in harmony with that.

Solving the Authentication Problem

What ways can a computer user use to prove she is who she says she is? There are really only four ways, and these pre-date computers though each has been implemented in software and hardware through a variety of means. None of them is perfect, but the more of them you use, the more secure your system is.

Authentication methods come in four types: something you know, something you have, something you are, and someone else vouching for you.

Something you know

Something you know is the most commonly used authentication method; we all know this when we are prompted to pick a password when signing up for a new website. They want this password to be difficult to guess because if someone else can somehow obtain, or guess, this knowledge, then they can gain access to anything you have access to. This knowledge-based authentication is represented in this famous quote from Brigham Young:

Your endowment is, to receive all those ordinances in the house of the Lord, which are necessary for you, after you have departed this life, to enable you to walk back to the presence of the Father, passing the angels who stand as sentinels, being enabled to give them the key words, the signs and tokens, pertaining to the holy priesthood, and gain your eternal exaltation.

-Brigham Young

Something you have

This quote also hints at the second authentication method, which is something you have. This is also known as token-based security. You see this when, after you sign in to your online banking, the bank sends a text message to your phone. They are assuming (not always correctly) that you and only you have access to your phone. A better system is a hardware-based security token that is handed to you, like this one I was issued in order to access my company’s VPN:

When I ended my employment, I surrendered my token to the company, and if I were to lose my token, the company could revoke its access to their internal systems. How does this fit into the temple? I refer you to the above quote from Brigham Young, which says the endowment issues us tokens (along with key words, or passwords) to allow us to attain our exaltation.

Something you are

Something you are uses some essential characteristic of who you are to prove you are who you say you are. Many smartphones these days have fingerprint, face, or iris scanners to unlock the phone once it is confident it’s actually you. If this system is implemented well, no one else but you can unlock it. In the temple, this is implemented a little differently. As we progress through the endowment, we make covenants. As we strive to keep those covenants through our lives, our character changes until we become the sort of people who are worthy of exaltation. A better analogy than information security is something like a diploma or guild membership–you put in the work, and you gain admission. While not foolproof, people who are motivated enough to do the work required for entry are usually also passionate about the area they are entering.

A trusted authority vouches for you.

A fourth security feature in information security is certificate-based authentication. While relatively new to computers, it is as old as time. In this scenario, a trusted authority issues you a certificate certifying you are who you say you are. Presumably, the certificate authority does due diligence to ensure I am who I say I am before issuing me a certificate. Then, when I present my certificate when attempting to gain access, if the system trusts the certificate authority, then it will also trust me. If this system is well implemented, it is considered one of the best ways to ensure proper authentication. If the certificate should somehow become compromised, the certificate authority can revoke the certificate through a certificate revokation list. Certificates also expire after a certain period of time (usually 2-3 years) and then must be reissued. (Much havoc ensues when IT administrators forget to renew these certificates before they expire.) Though uncommon, it is possible to implement a certificate system that is signed by more than one certificate authority.

The temple implements this system in a few ways. First, you must obtain a temple recommend in order to enter the temple. This must be signed by both a member of the Bishopric and a member of the Stake Presidency. Presumably, these people are familiar with your identity, and they also ask you questions to ensure you have the knowledge, experience, and commitment necessary to enter the temple.

Then, once you go to the temple, you are assigned an escort. This person helps you through the temple. Later on, someone vouches for you as worthy to continue to the most sacred part of the ceremony.

Access Control

Once you have gained access to a particular computer system, can you do everything in there? Usually, your access is monitored, controlled, and checked at multiple times. We have probably all seen an “access denied” error when we click on something on a website. We’ve also been annoyed at repeatedly being asked to enter our password. Access control and authentication are repeated at different stages and times to protect the information.

In the temple, access control begins at the recommend desk and continues until we enter the most sacred room. We are given several opportunities to determine if we wish to continue our progress, or stop it. We are warned that we will be accountable for keeping the promises we make, and for ensuring the security of the knowledge we obtain.

Why are these concepts so important to Temple worship?

The temple, it is fair to say, is quite concerned about authentication and access control. But why? I would suggest that they are important in temple worship because they are important to our discipleship.

Authentication in the early church

If we turn to an earlier time, and the teachings of Jesus and his early disciples, we can be reminded of some things that should not have been forgotten. In neglected second half of the parable of the wedding feast, Jesus tells us about a celebrant who is forcibly ejected from the festivities and “cast into outer darkness” for wearing the incorrect wedding garment. A few chapters later in Matthew, the five foolish virgins knock at the door of the wedding feast, only to be told, “I know you not.”

Jesus, Paul, and Peter, among many others all across the standard works warned about false prophets and false Christs. Authentication helps us distinguish between the wheat and the tares, the sheep and the wolves.

Authentication for determining the source of revelation

Equally important is our ability to recognize the source of the revelation we are receiving. We know that the adversary can impersonate an angel of light, and, if it were possible, “deceive the very elect.” We are encouraged to “try the Spirits” and take care that we are not deceived. All this emphasis in temple worship on ensuring that the messengers and messages come from Heavenly Father, and no other source, is a classic authentication problem, one upon which our eternal life depends. Moses is able to tell the difference between Satan and Heavenly Father because the former had no discernible glory, but Moses had something to compare it against.

Hugh Nibley talked about how if you were a feudal lord in service to a king, the king would take a stick and break it in half, sending one half with you back to your lands. If a messenger came claiming to be from the king, he could present the other half of the broken staff. If it matched up to the one you held, you knew the messenger was sent from the king. (This could be considered a key-pair authentication token in modern parlance.)

We have a similar process available to us. We can receive personal revelation, but if that doesn’t match up with what we read in the scriptures, or hear from the Lord’s ordained servants, then we can be assured the message is not from a divine source. Nibley pointed out that the “two sticks” mentioned in Ezekiel, the Bible and the Book of Mormon, perform and similar, mutually-authenticating function.

Sacred, or Secret?

The need for secrecy in some matters is a particularly hard thing for our present age to appreciate, when a torrent of information is available via search engine (though beware of its reliability), where reporters feel free to ask any number of questions of public officials, and where the most private words and actions of celebrities are leaked on the internet. It all seems so unnecessary in our age when just about everything is explained on YouTube, a Google search, or some Podcast.

The first reason why we have this is the Lord ensures that truths are imparted to us “line upon line, precept upon precept, here a little, there a little,” and as we hearken to each precept, the Lord provides us with more. This way He ensures that we are not accountable for knowledge which we are not ready to live by, or may not even be capable of following yet.

And yet each of us understands how intimacies can make a relationship more special. In high security environments, there is an area called a SCIF, or sensitive compartmented information facility. Certain sensitive information is provided only in a SCIF, and only to people allowed into the SCIF, to ensure that no other party may eavesdrop or obtain the information. You are not allowed to remove any information from the SCIF, or, typically, share it outside the SCIF.

In this way, the temple shares many functions with a SCIF, though there is something even richer lurking under the surface here. In his discussion of the white stone in the Book of Revelation, N. T. Wright compares the name written upon it that “no man knoweth save he that receiveth it” to secret shared between lovers:

Jesus is promising to each faithful disciple, to each one who ‘conquers’, an intimate relationship with himself in which Jesus will use the secret name which, as with lovers, remains private to those involved. The challenge to avoid the false intimacy of sexual promiscuity is matched by the offer of a genuine intimacy of spiritual union with Jesus himself.

N. T. Wright, Revelation for Everyone, p. 23.

This idea of the secrecy shared as an intimacy between two lovers is a rich metaphor worth pondering deeply.

Anyone with close friendships knows what a key role private, shared knowledge plays in generating that intimacy. For example, it may spark a memory of a time when someone embraced you and whispered something tender and beautiful in your ear, along with an affectionate pet name known only to that other person, as you were welcomed into some special place. It is not just secret information you are being given; this is not just being admitted to some special club–you are being keenly and warmly welcomed into a place where you are deeply known, and deeply loved. A little like coming home, only more so.

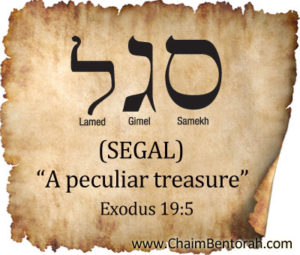

The secrecy reminds us how we are the Lord’s special treasure, and also places a burden upon us to be worthy of that trust and intimacy by respecting these same intimacies.

Conclusion

The temple endowment, as we can see, implements a multi-layered, “defense in depth” authentication and access control schemes in a variety of ways. The best security is multi-layered and multi-faceted.

It’s interesting that while the temple has ancient roots, it contains features that are used in the most modern computer systems. The principles we learn in the temple are timeless. More importantly, they are vital to our spiritual progress. They are not mere sterile, disembodied, abstract principles implemented into a set of ones and zeroes of binary code. In the temple, these ideas are brought to life, and demonstrated physically as well as intellectually. The secrets imparted there are not like some juicy gossip, rather, they are sacred truths imparted in a place of covenant, commitment, unity, in a place which connects us to our past and our future, our ancestors and posterity, and above all, reminds us of the incredible price the One who brings us such rich blessings paid.

Note: A special thanks to my friends Dan Ellsworth, J. Max Wilson, and Benjamin Pacini who each provided some valuable additional insights and references. Any errors or infelicities of phrasing remain my own, of course.

Continue reading at the original source →