The Know

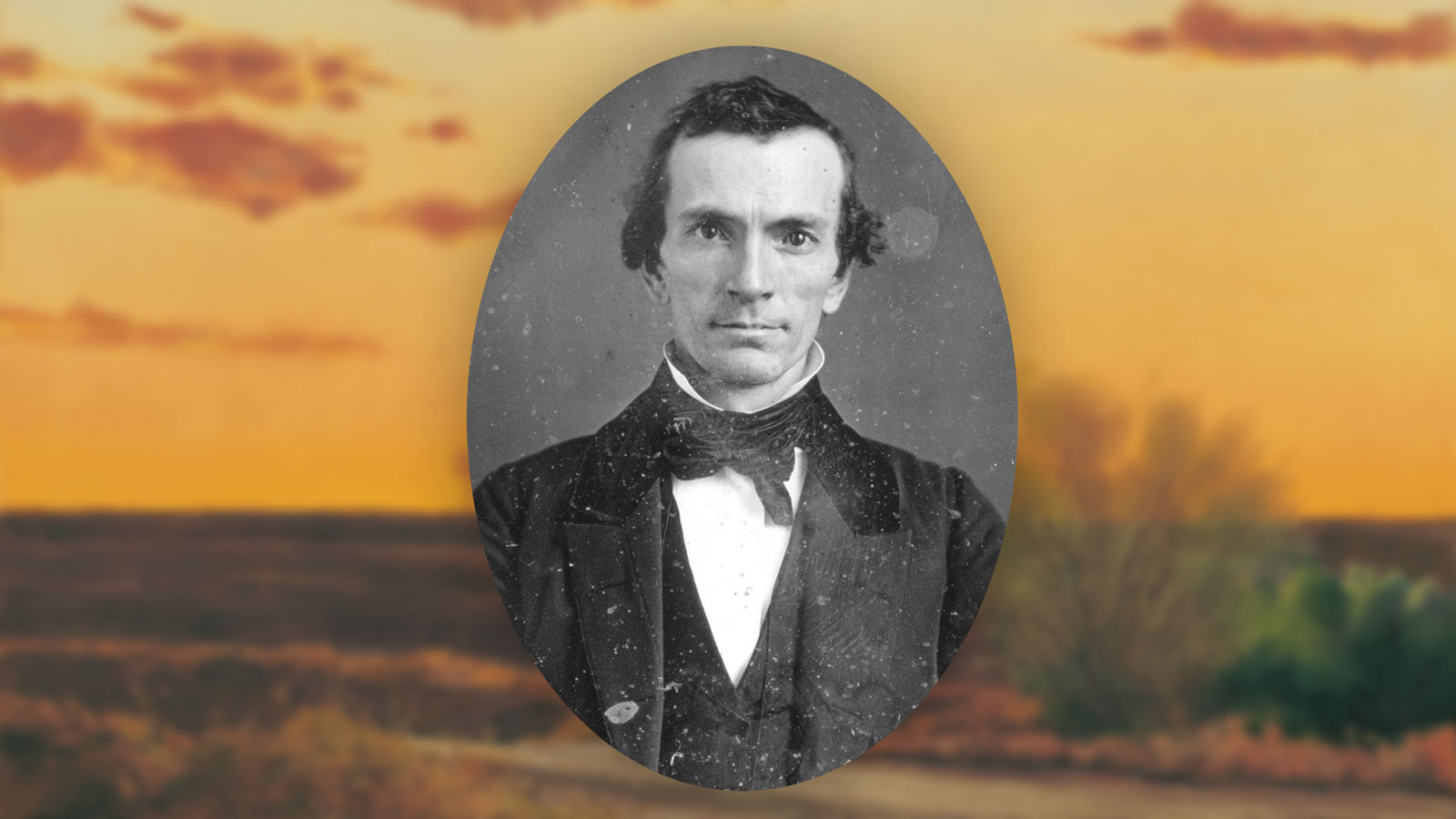

After the Prophet Joseph Smith, there was no more important witness of the early Restoration than Oliver Cowdery. Except Joseph, he was present during more of the translation of the Book of Mormon than any other person, and participated in several extraordinary Restoration events. Yet, despite those remarkable spiritual experiences, in 1837, a rift began to grow between Oliver and Joseph. The “second elder” (D&C 20:3) of the Church would be excommunicated on April 12, 1838, by the High Council in Far West, Missouri. This was a “common council of the Church” (D&C 107:82–84), presided over by Bishop Edward Partridge.1

The factors that resulted in this action are many and complex, and several important facts behind the nine (or ten) charges that were raised against Oliver are obscured from our complete view today. However, none of those charges had anything—directly or indirectly—to do with Oliver’s personal testimony of the Book of Mormon, which remained firm throughout his lifetime.2

It is important to understand that Oliver’s excommunication was not an isolated incident. Nine charges were brought against him, and on the very next day, apostle Lyman E. Johnson and fellow Book of Mormon Witness David Whitmer were both excommunicated on several of the same charges.3 The three cases were effectively bundled together, and all three cases were heard by virtually the same judges,4 none of whom were prominent leaders in the Church. Two of the judges, George Hinkle (who would soon turn traitor to the Saints) and George Harris, also volunteered as witnesses. Inevitably, in such a small community, all of these judges knew the three accused men personally.

Regarding the nine enumerated charges that were preferred against Oliver Cowdery, charges 4, 5 and 6 were eventually retracted by the court. On the remaining six charges, the court heard the testimony of ten witnesses5 upon which the decision of the court was based.6

“1st, For stiring up the enemy to persecute the brethren by urging on vexatious Lawsuits and thus distressing the innocent” and “7th, For leaving the calling, in which God had appointed him, by Revelation, for the sake of filthy lucre, and turning to the practice of the Law.”

When Oliver moved to Missouri in 1837, he sought to alleviate personal debts by starting a legal career.7 Witnesses testified that Oliver had urged people to sue others in court who “fired guns in town,” who broke “the Sabbath day,” he “frequently solicited for business in collecting debts,” and “urge[d] on lawsuits with others.” Ample testimony sustained charges 1 and 7, although Oliver was only acting as lawyers normally would.

“2nd, For seeking to destroying the character of President Joseph Smith jr, by falsly insinuating that he was guilty of adultry &c.”

David Patten reported that Oliver privately told him about an “adultery scrape,” which Joseph had supposedly “confessed to Emma.” Thomas Marsh testified that Oliver was once asked if Joseph “had ever confessed to him that he was guilty of adultery,” to which Oliver had answered “no,” but only after “a considerable winking, &c,” apparently thereby insinuating (incorrectly) that it was actually true. Joseph then asked Marsh “if he [Oliver] ever told him that he [Joseph] confessed to any body,” to which Marsh answered, “no.” Hence, charge 2 was found to be sustained regarding Oliver having made false insinuations.

At that point in the trial, Joseph Smith himself took the witness stand. He “testifie[d] that Oliver Cowdery had been his bosom friend, therefore he intrusted him with many things. He [Joseph] then gave a history respecting the girl business,” which must have satisfied the court, in some credible way, that whatever had gone on between Joseph and Fanny Alger (Emma’s domestic girl, who left Kirtland in 1836)8 was not to be seen as unacceptable. Otherwise, the court would not have found Oliver guilty of charge 2.

“3rd, For treating the Church with contempt by not attending meetings.”

This was supported by John Corrill, who summarily stated that Oliver had “neglected attending meeting,” to which judge and witness George Harris concurred. Oliver had served as the clerk of Church council meetings as recently as March 10, 1838, but apparently had not been attending regular church meetings very often, although he had been terribly ill for six weeks and on assignment in Davies County.

“8th, For disgracing the Church by Lieing being connected in the ‘Bogus’ buisness as common report says” and “9th, For dishonestly Retaining notes after they had been paid and finally for leaving or forsaking the cause of God, and betaking himself to the beggerly elements of the world and neglecting his high and Holy Calling contrary to his profession.”

The remaining charges 8 and 9 were strongly supported by witness statements testifying that: (a) Oliver had been involved with printing counterfeit currency and was almost arrested in Kirtland for making dies to print “bogus money,” but had left to avoid having to stand trial; (b) that he had dishonestly taken with him a printing press and type from Kirtland; (c) and that he had failed to surrender promissory notes extended to him by Joseph and Sidney.

In sum, the council held that Oliver had “forsak[en] the cause of God, and betaking himself to the beggarly elements of the world and neglecting his high and Holy Calling’ contrary to his profession.” After hearing all of the evidence, Bishop Partridge and the council made the determination that six of the charges against Oliver were sustained, justifying their decision that Oliver “was considered no longer a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.” These were all the grounds on which Oliver was excommunicated.

The Why

Why Oliver Cowdery’s excommunication happened is a fraught question—there were many reasons, all of them regrettable. As the minutes of his excommunication hearing reveal, a central feature of Oliver’s dissent was the interference of Church leadership in the temporal concerns of members. This issue had already ripped the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in half in Kirtland in 1836, leading to the departures of William E. McLellin, Luke S. Johnson, John F. Boynton, and Lyman E. Johnson.

By the time that Cowdery’s own trial was held in April 1838, relationships with Church leaders were such that neither he, nor Lyman E. Johnson or David Whitmer attended in person.9 Instead, Oliver chose only to send a letter to Bishop Partridge in response to three of the charges (nos. 4, 5, and 6) laid against him, foreclosing opportunities to reconcile, work out differences, and renew unity of the faith with dear friends and fellow laborers in the Kingdom.

Deeper than mere disputes over property, however, was Oliver’s more fundamental rejection of all Church authority. He refused to be governed by any ecclesiastical authority, and thus admitted that he had sold his lands in Jackson County contrary to the instructions given to him by revelation of those in leadership capacities. This argument was not original with Oliver. It was a common antiestablishment tenet of many Protestant churches that emerged in the wars of the Reformation, which were fought against the political and property controls exercised by the central Roman Catholic Church. It was this principle that led the Pilgrims to flee to America, some of whom Oliver proudly claimed as his venerable ancestors.

Some people have also wondered if Oliver felt rejected when the Church officers were reconstituted at the conference in Far West on November 7, 1837. Joseph Smith Jr. was unanimously chosen. Sidney Rigdon was also unanimously chosen as First Counselor. But when Frederick G. Williams was debated and rejected, Hyrum Smith was elected Second Counselor. Oliver was not even considered.10

In addition, Oliver took another step away from the organized Church. Instead of accepting even a limited form of organizational association and community obligation, he stressed that he would be “influenced, governed, or controlled” only by his “own judgment.”11 Oliver went too far in not recognizing any of his own failings or duties to the community of faithful believers. Instead, he turned to ridicule, insults, accusations, and making the overstated claim that the leaders were attempting “to set up a kind of petty government.”12 He would later regret his loss of association with the Saints, whom he dearly loved; but in the meantime, he and others languished.

Oliver declined to answer any of the other charges, writing, “I shall lay them carefully away, and take such a course with regard to them, as I may feel bound by my honor, to answer to my rising posterity.”13 Instead of dealing promptly with the problem, Oliver ended up being excommunicated because he thought he could ignore the present and sweep the problems aside, to deal with them at some vague time in the future. Obviously, this was not a wise choice, for the future may not afford such an opportunity. As things will turn out, Oliver would have only a dozen more years to live. In the end, he left little by way of “answer to [his] rising posterity” or to his brothers and sisters in the Gospel.

Believing that Church leaders were overstepping their bounds, and were trying “to take from me a portion of my Constitutional privileges and inherent rights,” Oliver decided “to withdraw from a society [for] assuming they have such right.”14 Here, Oliver tried to shift the blame to the Church, rather than at least asking to some extent, “Lord, is it I?” Thus, even if the council had not chosen to excommunicate him, Oliver had already withdrawn from Church membership on his own initiative. In essence, he was not excommunicated; rather, he stepped away.

Although Oliver left the Church for a time—for many reasons, but principally over bureaucratic and ecclesiastical conflict with Church leadership—he never wavered in his testimony of the Book of Mormon or of the divine origins of the Restoration. At a chance meeting later that summer, Thomas B. Marsh, who by that point had also left the Church, asked Oliver Cowdery and David Whitmer if they still held to their testimony of the Book of Mormon. They both answered with an emphatic, “Yes.”15 Ten years after his excommunication, Oliver Cowdery returned to the Church and was rebaptized.16

Further Reading

Scott H. Faulring, “The Return of Oliver Cowdery,” in Oliver Cowdery: Scribe, Elder, Witness, ed. John W. Welch and Larry E. Morris, (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2006), 321–362.

Jeffrey N. Walker, “Oliver Cowdery’s Legal Practice in Tiffin, Ohio,” in Days Never to be Forgotten: Oliver Cowdery, ed. Alexander L. Baugh (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Religious Studies Center, 2009), 295–325.

Richard Lloyd Anderson, “Cowdery, Oliver,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4 vols., ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 1:335–340.

- 1. The other members of the High Council present when Oliver was put on trial were Samuel H. Smith, Jared Carter, Thomas Grover, Isaac Higbee, Levi Jackman, Solomon Hancock, George Morey, Newel Knight, George M. Hinkle, George W. Harris, Elias Higbee, and John Murdock. See Minute Book 2, 12 April 1838, pp. 118.

- 2. For a useful summation of Oliver Cowdery’s life, see Richard Lloyd Anderson, “Cowdery, Oliver,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4 vols., ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 1:335–340.

- 3. Charges that were brought against all three of them included (a) neglecting to attend meetings, (b) writing insulting letters to the high council, (c) injuring the character of Joseph Smith, (d) damaging the reputation of the Church; and charges against two of them were (e) suing or threatening to bring lawsuits, (f) telling falsehoods, (g) aligning with the dissenters in Kirtland, (g) neglecting their high and holy calling, and (h) not keeping the Word of Wisdom. In addition, other particular charges were brought against each of them individually.

- 4. Ten of the twelve judges were the same in all three cases.

- 5. The witnesses were as follows: 4 on charges 1 and 7 (John Corrill, John Anderson, Dimick Huntington, George Hinkle), 4 on charge 2 (George Harris, David Patten, Thomas Marsh, Joseph Smith), 2 on charge 8 (Frederick Williams, Joseph Smith), and 2 on charge 9 (Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon).

- 6. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes are from the Far West Record (Minute Book 2), 12 April 1838, pp. 118–126, online at josephsmithpapers.org.

- 7. Richard Lloyd Anderson, “Oliver Cowdery, Esq.: His Non-Church Decade,” in To the Glory of God: Mormon Essays on the Great Issues—Environment, Commitment, Love, Peace, Youth, Man, ed. Truman G. Madsen and Charles D. Tate (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1972), 200.

- 8. For present purposes, the facts and opinions concerning when any such relationship could have occurred are widely divergent. See Brian C. Hales, “Fanny Alger and Joseph Smith’s Pre-Nauvoo Reputation,” Journal of Mormon History (Fall 2009): 139–177. It would answer many questions if we only knew a little more about what Joseph gave as his side of this history on this early occasion in April 1838. Even before the middle of January, Joseph had said “publickly” in Kirtland that Oliver “had confessed to [Joseph] that [he, Oliver] had willfully lied” about Joseph, for which Oliver hoped for “an explanation,” but until that time Oliver said that he and Joseph would remain “two.” The larger matter of Joseph Smith’s institution of polygamy as a part of the restoration of all things will be discussed in a later KnoWhy, dealing especially with Doctrine and Covenants 132.

- 9. See “Historical Introduction,” Minutes, 12 April 1838, in online on josephsmithpapers.org.

- 10. Far West Record (Minute Book 2), 7 November 1837, pp. 82–83, online at josephsmithpapers.org.

- 11. Far West Record (Minute Book 2), 12 April 1838, pp. 120–121, online at josephsmithpapers.org.

- 12. Far West Record (Minute Book 2), 12 April 1838, pp. 121, online at josephsmithpapers.org.

- 13. Far West Record (Minute Book 2), 12 April 1838, pp. 122, online at josephsmithpapers.org.

- 14. Far West Record (Minute Book 2), 12 April 1838, pp. 121, online at josephsmithpapers.org.

- 15. “History of Thomas Baldwin Marsh,” Deseret News, 24 March 1858, 18.

- 16. See Scott H. Faulring, “The Return of Oliver Cowdery,” in Oliver Cowdery: Scribe, Elder, Witness, ed. John W. Welch and Larry E. Morris, (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2006), 321–362.

Continue reading at the original source →