The Know

In a revelation given to the elders of the Church through the Prophet Joseph Smith on September 11, 1831, the Lord promised to preserve Kirtland as “a strong hold … for the space of five years” (D&C 64:21).1 In those years, the Church in Kirtland grew and flourished, culminating with the dedication of the Kirtland temple in March 1836, an event that was accompanied with many divine manifestations and profound spiritual experiences.2

By this time, the Church had accrued significant debts both from the construction of the Kirtland temple as well as various business endeavors. After the dedication of the temple in the spring, Joseph and other Church leaders turned their attention to both alleviating these debts and also building up Kirtland’s economy. Compounding these challenges, many Saints who migrated to Kirtland were poor and in desperate need of economic opportunities. Church leaders were looking to provide for these Saints and pay-off debts at the same time.3

Over the summer, Joseph and other Church leaders engaged in various efforts designed to grease the wheels of Kirtland’s economy and also resolve the Church’s debts. However, these efforts were often complicated by other prominent members and leaders who established competing businesses and bought up land, driving up real estate prices and then seeking to turn a profit.

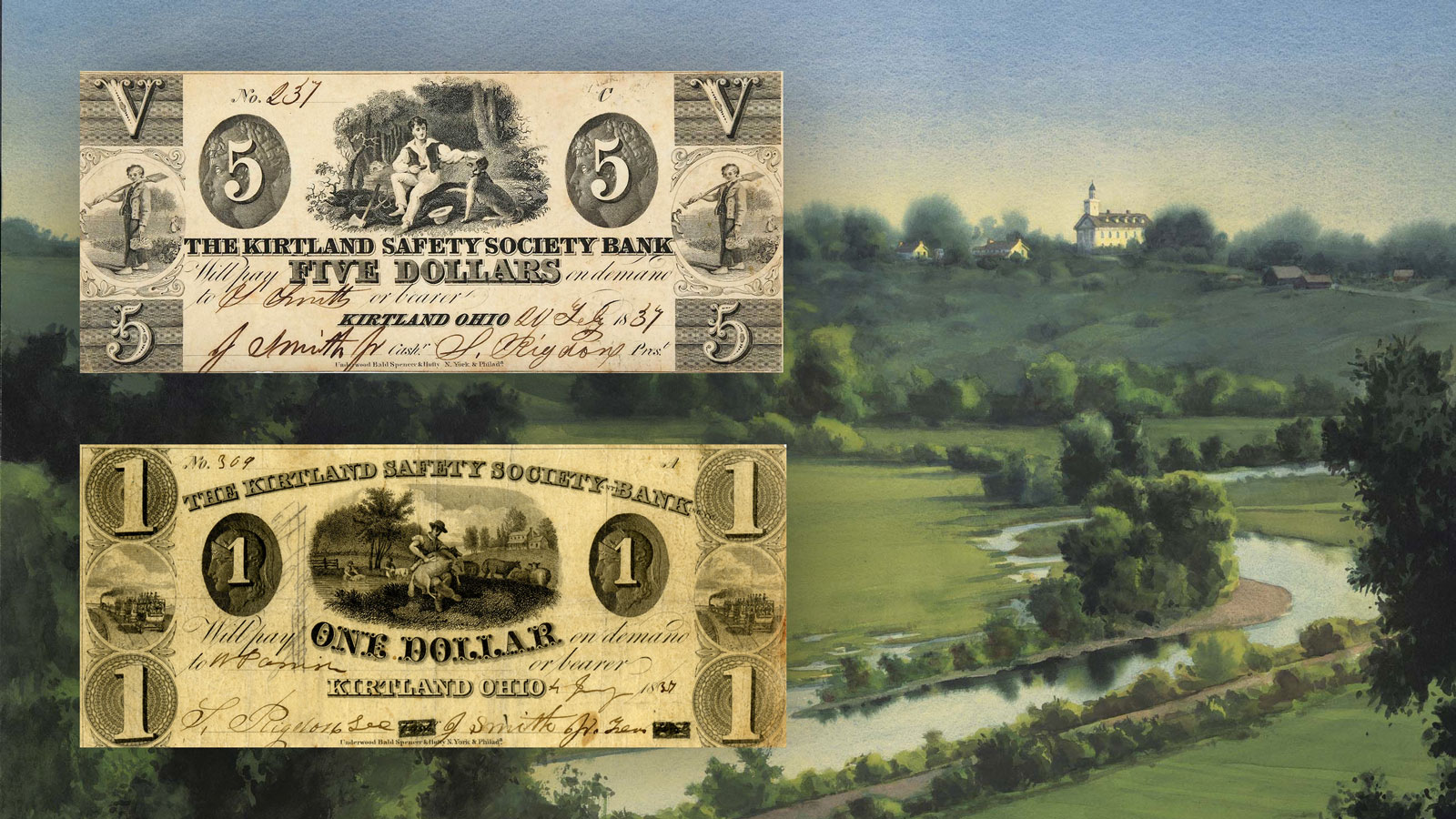

On September 12 or 13, 1836, Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, Hyrum Smith, and Oliver Cowdery returned from a trip to Salam, Massachusetts “with a clear sense of direction” to “establish a bank and acquire land” as a solution to the Church’s economic problems.4 In the 1830s, banks could acquire capital in the form of hard currency (gold and silver coin), land deeds, and other assets; they then issued short-term loans in the form of “bank notes,” which were essentially debts that could be exchanged at the bank for hard money. If the institution issuing the banknotes was trusted and respected in the community, their notes could be exchanged between individuals as actual currency. Thus, banks enabled frontier economies like Kirtland’s to transform non-liquid assets (such as land) into liquid assets (bank notes).5

By September 14, 1836 the firm of Smith, Rigdon, & Cowdery was already acquiring property and other assets intended to be used in their banking endeavor.6 About a month later, people were purchasing stock in the yet-to-be-formed bank.7 Then on November 2, 1836, some of the “brethren of Kirtland” came together to officially organize a banking institution, which they called the Kirtland Safety Society.8 They named six people as a “committee of directors”: Sidney Rigdon, Joseph Smith Jr., Frederick G. Williams, Reynolds Cahoon, David Whitmer, and Oliver Cowdery.9

The next two months were spent addressing logistical issues, such as procuring plates for printing bank notes, constructing a building from which they would operate, and trying to obtain a banking charter from the Ohio legislator.10 State issued bank charters provided assurance that an institution was legitimate and provided some backing should it fail; but it was not uncommon at the time for many financial institutions to operate without a charter.11 Laws relating to unchartered banks were relatively new, and were not yet tested in court.12

As first constituted, the Kirtland Safety Society intended to operate as an officially state-chartered bank. Due to a variety of circumstances, including the political maneuvering of the Saints’ enemies, they were unable to obtain a charter from the Ohio legislature before they opened in January 1837. So instead of being a chartered corporation, they reorganized as a “joint stock company”—what one would called today a “general partnership”—and began issuing bank notes January 9, 1837.13

It was not uncommon for new banking institutions to operate for a brief period before obtaining a charter, in order to demonstrate the institution’s viability to the state legislators. This seems to have been the intent of the Kirtland Safety Society, as they continued to pursue two different avenues to procuring a charter after opening. First, they made a second attempt with the state legislature, which got voted down on February 10, 1837.14 This is unsurprising, since only one bank’s application was accepted by the state of Ohio that year.15

That same day, Joseph Smith and others were meeting with officials of the Bank of Monroe, in Michigan, to initiate their second strategy for gaining a charter. Ohio recognized the legitimacy of banking charters from other states, which allowed out of state banks to establish branches in Ohio. Joseph and officers of the Kirtland Safety Society were essentially seeking a merger—their business association would purchase a controlling interest in the stock of Bank of Monroe, and the Kirtland operation would thus become a branch of the Michigan-chartered bank.16 To accomplish this legally, independent lawyers drafted a new partnership agreement, which was signed and published. As part of the deal, Oliver Cowdery was made director and vice president of the Bank of Monroe, and was authorized to sign bank notes that were used as currency on the credit of that bank.17

Thus, with its charter issues—and the accompanying rumors of its illegitimacy—legally and effectively resolved, the Kirtland Safety Society seemed poised to bring the much-needed economic relief to members of the Church in Kirtland. Unfortunately, outside factors instead led to its demise, and the Kirtland bank officially closed its doors in September 1837, leaving its thirty-two18 partners and directors each individually and jointly liable for all of that branch’s financial obligations.

The Why

Several factors contributed to this eventual closure. “Within a week of opening,” according to the recent analysis of legal historian Jeffrey Walker, “initial efforts generated the exact result hoped for—increased economic activity.”19 Shortly after this initial success, however, “concerted attacks on the venture” began, led by an unscrupulous competitor named Grandison Newell.20

Newell lived in nearby Painesville, a neighboring town with aggressively competing economic interests and a hotbed for anti-Mormon activity and publications. Newell was directly involved in various business interests that would have been negatively impacted by any success of the Kirtland Safety Society. So, he took it upon himself to ensure its failure. Newell bragged that he personally bought up as many of the Kirtland bank notes as he could (probably paying less than face value), and then sought to redeem them for hard currency, thus depleting the Kirtland Safety Society’s liquid capital reserves.21

In connection with this “organized mobbing and run on the bank” by Newell, rumors were started that Kirtland Safety Society vaults were empty, and that its officers were refusing to exchange banknotes for gold and silver coin, which was scarce.22 Although the rumors were likely unfounded, since “the validity of paper money of any kind has always been an act of faith,” the mere accusation was enough to undermine people’s trust in the Kirtland banknotes, not allowing the principals behind the Society even a week or two to liquidate their assets in order to cover the issued notes that were now being surrendered.23

Then, in February 1837, Newell used Samuel Rounds as a front for a lawsuit against Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and others as leading officers of the Kirtland Safety Society. The charges were brought on the basis of an 1816 Ohio law which originally imposed a $1000 penalty against any officers of an unincorporated bank. Half of that penalty could be collected by any “informer” who brought cases of such to the attention of the state.24

This 1816 law, however, had actually been superseded by an 1824 statute which did not stipulate penalties for unincorporated bankers, but instead simply made the banknotes from such banks unenforceable in a court of the law. This clear effect of the 1824 statute was confirmed by an Ohio Supreme Court ruling in 1840.25 Joseph and Sidney’s 1837 trial, however, preceded that ruling, and thus in 1837, there appears to have been some uncertainty about how the 1824 statue related to the earlier 1816 law.

Joseph and Sidney’s defense attorney brought up the suspension of the 1816 act, as well as other important legal distinctions—such as the reorganization of the Kirtland Safety Society as a “joint stock company”—but a jury ultimately ruled in Rounds’ (and Newell’s) favor. A $1000 penalty was assessed to both Joseph and Sidney, half of which was rewarded to Newell, and the other half was to go to the state. The legal proceedings of this action unfolded over the course of most of that year, but by November 1837, Newell had collected more than what was owed, and he never forwarded half of the recovered amount to the state, thereby defrauding the state of Ohio.26

In the meantime, other events transpired to seal the fate of the Kirtland Safety Society. The country’s 1837 banking crisis hit Ohio and Michigan in February and March, and many banks were forced to close their doors—including the Bank of Monroe.27 This unforeseeable national crisis could not have been more unfortunate for the fragile Kirtland economy. The merger between the Kirtland and Monroe financial institutions had briefly buoyed up the Safety Society, but when the Bank of Monroe closed, that financial relationship was severed, and Oliver returned to Kirtland.28

Understandably, disagreement and disaffection took its toll in many parts of the country, and some of the principal investors in the Kirtland Safety Society left the Church and illegally withdrew their assets from that Society. In June 1837, Joseph and Sidney resigned as officers of the financial institution, and its assets and business affairs were left in the hands of Warren Parrish and Frederick G. Williams, who had both disaffected for a time from the Church. Accusations of forgery and embezzlement were directed at Parrish and others.29 In a letter published in the August issue of the Messenger and Advocate, Joseph Smith gave notice to the Saints and the public in general about the risks of doing business with the Kirtland Safety Society going forward.30

Given all this surrounding economic, personal, and legal turmoil, it is no wonder that this banking endeavor ultimately closed its doors.31 Despite these challenges, however, virtually all of the deposits documented in 27 collection cases were ultimately returned to Kirtland Safety Society investors.32

For some living in Kirtland at the time, however, this development was seen as evidence of the Prophet Joseph Smith’s moral failings and a lack of prophetic foresight. They misunderstood the conditional nature of prophetic promises, and thought the success of the venture had been assured. In reality, Joseph had only ever promised that “if we would give heed to the Commandments” of the Lord, “all would be well.”33 As Mark Staker noted, “Clearly, Joseph had not told his fellow believers that their efforts were failure-proof.”34

Amidst all the chaos, the dissenters had apparently overlooked the impressive fulfillment of a prophetic utterance. When plans for starting a bank had been set in motion in mid-September 1836, it was nearly five years to the day after the Lord had promised, through Joseph Smith, that Kirtland would remain “a strong hold … for the space of five years” (D&C 64:21).35 This five-year prophecy was not only a promise, but came with an express warning. The Lord admonished “that ye ought to forgive one another” and not seek “occasion against [Joseph] without cause” (D&C 64:9, 6). With the five-year stronghold period expired, the events involving the Kirtland Safety Society ultimately led to the temporary relocation of the leadership of the Church to Far West, Missouri and the end of the Kirtland era of Church history.

Further Reading

Jeffrey N. Walker, “Looking Legally at the Kirtland Safety Society,” in Sustaining the Law: Joseph Smith’s Legal Encounters, ed. Gordon A. Madsen, Jeffrey N. Walker, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2014), 179–226. Revised and expanded as “The Kirtland Safety Society and the Fraud of Grandison Newell: A Legal Examination,” BYU Studies Quarterly 54, no. 3 (2015): 33–148.

Gordon A. Madsen, “Tabulating the Impact of Litigation on the Kirtland Economy,” in Sustaining the Law: Joseph Smith’s Legal Encounters, ed. Gordon A. Madsen, Jeffrey N. Walker, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2014), 227–246.

Mark L. Staker, “Raising Money in Righteousness: Oliver Cowdery as Banker,” in Days Never to be Forgotten: Oliver Cowdery, ed. Alexander L. Baugh (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Religious Studies Center, 2009), 143–253.

Mark Lyman Staker, Hearken, O Ye People: The Historical Setting for Joseph Smith’s Ohio Revelations (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2009), 391–558.

- 1. The earliest extant copy of this revelation was copied into Revelation Book 1 by John Whitmer, ca. September 1831. In that version, this passage reads, “for I the Lord willeth to retain a strong hold in the Land of Kirtland for the space of five years.” See Revelation, 11 September 1831, online at josephsmithpapers.org.

- 2. On these early Kirtland years in the Church, see Milton V. Backman, “Kirtland, Ohio,” in Doctrine and Covenants Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey and Larry E. Dahl (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2012), 344–346; Karl Ricks Anderson, “Kirtland, Holy Ground of our Dispensation,” Book of Mormon Central Fireside, April 11, 2021, online at youtube.com. On the spiritual events related to the dedication of the Kirtland temple, see Milton V. Backman, “Kirtland Temple Dedication,” in Doctrine and Covenants Reference Companion, 347–348; Steven C. Harper, “‘A Pentecostal Endowment Indeed’: Six Eyewitness Accounts of the Kirtland Temple Experience,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestations, 1820–1844, 2nd ed., ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Press, 2017), 351–393; Steven C. Harper, “Joseph Smith and the Kirtland Temple, 1836,” in Raising the Standard of Truth: Exploring the History of the Teachings of the Early Restoration, ed. Scott C. Esplin (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Religious Studies Center, 2020), 211–230.

- 3. See Mark Lyman Staker, Hearken, O Ye People: The Historical Setting for Joseph Smith’s Ohio Revelations (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2009), 435–462. For a detailed look at Kirtland’s economy in the 1830s, see Marvin S. Hill, C. Keith Rooker, and Larry T. Wimmer, “The Kirtland Economy Revisited: A Market Critique of Sectarian Economics,” BYU Studies 17, no. 4 (1977): 391–472.

- 4. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 452, 463. Joseph Young to Lewis Harvey, November 6, 1880, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City stated, “The prophet had conceived a plan of instituting a Bank, with a view of relieving their financial embarrassment”. This decision may be hinted at by Oliver Cowdery’s mention of the firm of Draper, Underwood, which Cowdery noted was “ready to help incorporated bodies to plates and dyes” to print banknotes. “Dear Brother,” Messenger and Advocate 2 (September 1836): 375.

- 5. See Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 447. The ability to issue bank notes was not actually limited to banks, and many businesses on the 1830s, including real estate associations, railroad companies, and libraries were issuing bank notes in Ohio at the time. See Dale W. Adams, “Chartering the Kirtland Bank,” BYU Studies 23, no. 4 (1983): 470–471.

- 6. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 453.

- 7. Paul Sampson and Larry T. Wimmer, “The Kirtland Safety Society: The Stock Ledger Book and the Bank Failure,” BYU Studies 12, no. 4 (1972): 427-429; Howard Bodenhorn, State Banking in Early America: A New Economic History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 19, “Early bank shares typically had a par value of $400 or $500.” Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 463–464 notes that stocks for the Kirtland Safety Society were deliberately made more affordable than was typical for most banking institutions, to allow ordinary citizens (and not just the wealthy) to be able to invest in the bank.

- 8. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 464–465.

- 9. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 465.

- 10. See Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 467–480.

- 11. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 447.

- 12. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 448.

- 13. Jeffrey N. Walker, “Looking Legally at the Kirtland Safety Society,” in Sustaining the Law: Joseph Smith’s Legal Encounters, ed. Gordon A. Madsen, Jeffrey N. Walker, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2014), 180–188. See also Jeffrey N. Walker, “The Kirtland Safety Society and the Fraud of Grandison Newell: A Legal Examination,” BYU Studies Quarterly 54, no. 3 (2015): 35–48.

- 14. See Adams, “Chartering the Kirtland Bank,” 477–479.

- 15. This was no doubt due to the collapse of local banks all over the country, due largely to the closing of the United States national bank when Andrew Jackson’s party lost the White House in the November 1836 election.

- 16. For the legal details of this arrangement, see Walker, “Looking Legally,” 189–190; Walker, “Fraud of Grandison Newell,” 50–54.

- 17. See Mark L. Staker, “Raising Money in Righteousness: Oliver Cowdery as Banker,” in Days Never to be Forgotten: Oliver Cowdery, ed. Alexander L. Baugh (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Religious Studies Center, 2009), 176–177.

- 18. Staker, “Raising Money in Righteousness,” 205–206 n. 47.

- 19. Walker, “Looking Legally,” 188; Walker, “Fraud of Grandison Newell,” 48.

- 20. Walker, “Looking Legally,” 188–189.

- 21. Walker, “Looking Legally,” 189; Walker, “Fraud of Grandison Newell,” 49.

- 22. Paper money did not yet exist as “legal tender” yet. That step would not be taken in the nation’s economic history until Abraham Lincoln would be forced to begin issuing paper currency, backed by the full faith and credit of the United States, in order to finance the Civil War in the 1860s.

- 23. Staker, “Raising Money in Righteousness,” 171–172.

- 24. See Walker, “Looking Legally,” 197; Walker, “Fraud of Grandison Newell,” 61–63.

- 25. Walker, “Looking Legally,” 197–201; Walker, “Fraud of Grandison Newell,” 63–66.

- 26. For detailed review, see Walker, “Looking Legally,” 196–226; Walker, “Fraud of Grandison Newell,” 66–98. Twenty years later, Newell would claim this case was never settled, and through a series of deceptions convinced the Ohio legislator to pass the “Relief of Newell Act” in 1859, permitting him to collect on the case again, and thus defrauding the state a second time. See Walker, “Fraud of Grandison Newell,” 98–139.

- 27. See Scott H. Partridge, “The Failure of the Kirtland Safety Society,” BYU Studies 12, no. 4 (1972): 437–454.

- 28. Staker, “Raising Money in Righteousness,” 177–193.

- 29. Oliver Cowdery may have been among these, as during his excommunication trial in April 1838, Oliver was implicated in plans to forge paper money. It is unclear if this was related in anyway to the Kirtland Safety Society or not. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Was Oliver Cowdery Excommunicated from the Church? (D&C 20:3),” KnoWhy 603 (May 11, 2021).

- 30. Walker, “Looking Legally,” 193–195; Walker, “Fraud of Grandison Newell,” 54–59.

- 31. As part of the larger national context, it is significant that the first bankruptcy laws in the nation would be adopted by Congress on August 19, 1841, in the wake of the nationwide depression that began with this panic of 1837. See Joseph I. Bentley, “Suffering Shipwreck and Bankruptcy in 1842 and Beyond,” in Sustaining the Law, 315–319.

- 32. See Gordon A. Madsen, “Tabulating the Impact of Litigation on the Kirtland Economy,” in Sustaining the Law, 227–246.

- 33. As cited in Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 481.

- 34. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 481.

- 35. Published as Section 65:27 of the 1833 Book of Commandments, and as Section 21:4 of the 1835 first edition of the Doctrine and Covenants.

Continue reading at the original source →