The Know

Martin Harris was among the very earliest supporters of Joseph Smith.1 He assisted early on with the translation of the Book of Mormon, and against the advice and social pressure of friends and neighbors he provided financially for the printing of the Book of Mormon.2 Martin was there on April 6, 1830, when the Church was organized, and was baptized by fellow Book of Mormon witness Oliver Cowdery shortly after the meeting.3

Over the next several years, Martin moved to Kirtland and played an active part in the Restoration. He continued to contribute financially to the building up of Zion, marched to Missouri and back in Zion’s Camp, and was called as a member of the Kirtland High Council. He participated in ordaining the initial quorum of the Twelve Apostles in 1835, and in the divine endowments associated with the Kirtland Temple in March 1836. Through all these various activities, Martin regularly bore testimony of the Book of Mormon as one of the Three Witnesses.4

By the end of the tumultuous economic year of 1837, however, Martin stood apart from Joseph Smith and the mainstream Church. In a letter written by John Smith, at the time an assistant counselor in the First Presidency, Martin was listed alongside Joseph Coe, Luke Johnson, John Boynton, and Warren Parrish as one of the leaders of an splinter group. John Smith called a high council to consider the case of these and other men, and reported that they had been “cut off … from the Church.”5 Based on this letter, it seems that Martin was either excommunicated or disfellowshipped in late December 1837, though no official record of the disciplinary action survives today and it is unclear whether he was even present at that meeting.6

Due to this lack of direct documentation for the disciplinary council, the exact charges raised against Martin are unknown. It is clear, however, that over the course of 1837, Martin became increasingly aligned with dissenters who sought to replace Joseph Smith and others as leaders of the Church in Kirkland.

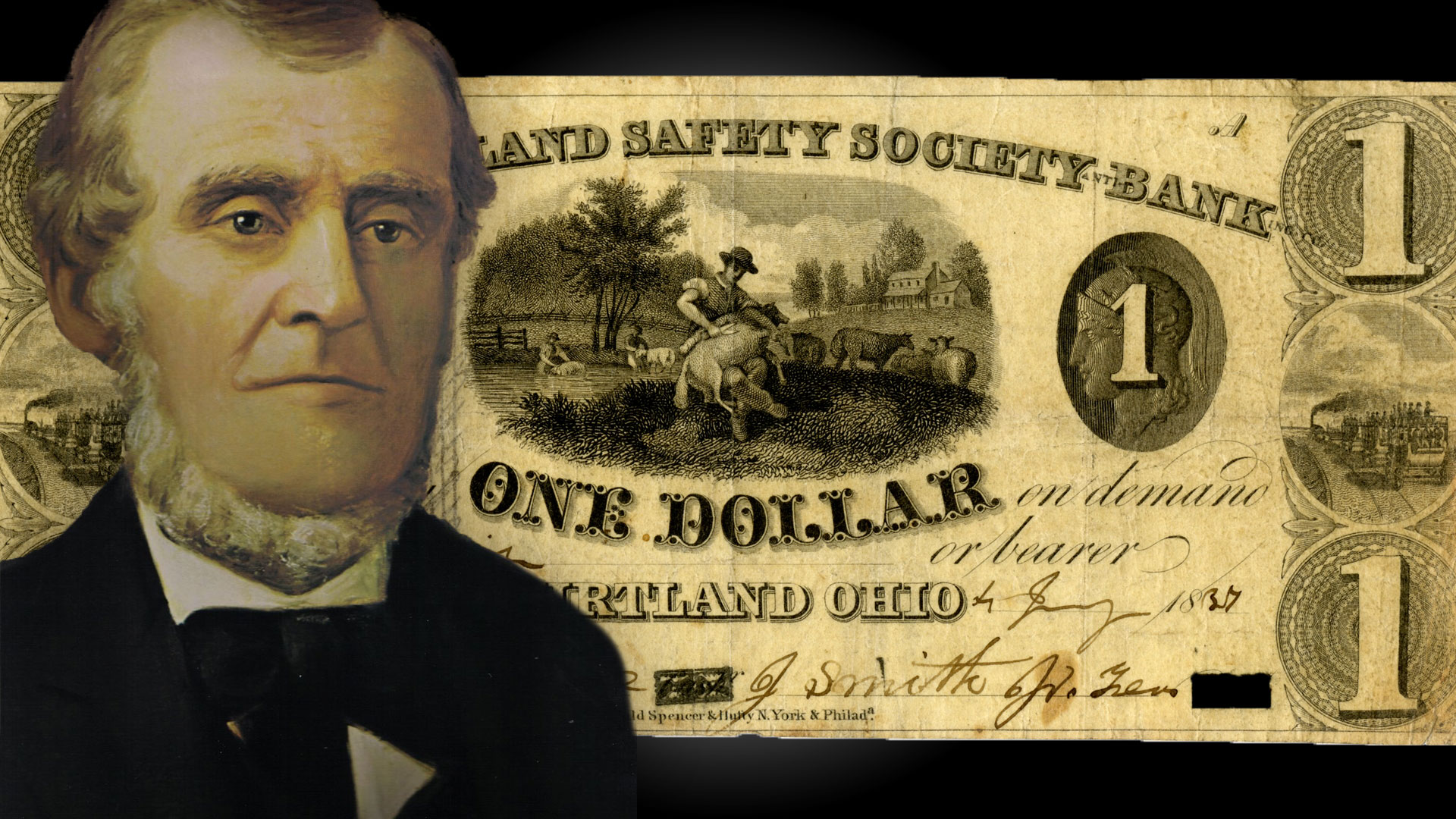

By 1837, the Church had accrued significant debts and the Kirtland economy had begun to stagnate. To alleviate these problems, Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, Oliver Cowdery and others started a private bank called the Kirtland Safety Society, which officially opened in January 1837.7 The Saints were encouraged to invest in the bank and circulate its bank notes, but Martin Harris—whose substantial financial resources could have greatly aided the banking endeavor—is completely absent from the list of investors.8

Instead of assisting Joseph and others in building up Kirtland’s economy, Martin left for an extended stay in Palmyra in the early part of 1837. Martin still remained on good personal terms with Church leaders at this time—he provided lodging to Brigham Young and Willard Richards when they passed through the Palmyra area fund-raising for the Kirtland Safety Society in March 1837. He also gave Joseph and Sidney Rigdon a safe haven in New York when they had to leave Kirtland for their own safety in April. On neither occasion, however, did Martin use his financial means to alleviate the situation in Kirtland, although he was almost certainly asked to do so.9

As the Kirtland banking venture struggled, Martin purchased land in Palmyra for $900, and when he returned to Kirtland in May, he spent more than $5,000 on a 250-acre farm there.10 Why Martin withheld of his financial means at this time and instead made substantial purchases for his own ends is unclear. Martin may have held anti-banking sentiments, and reportedly clashed with Sidney Rigdon over it.11 This may have led to him distrusting the paper money distributed by the Safety Society and refusing to invest. Whatever the reason, the Martin clearly acted in opposition to the council of Church leaders by refusing to aid the Church’s economic needs in Kirtland.

By the fall of 1837, the Kirtland Safety Society collapsed and disappointment and dissent swept through Kirtland. At a conference held in early September, Martin Harris and several other individuals holding high callings were not sustained by the unanimous vote of the congregation.12 The reasons for the objection to Martin’s standing on the Kirtland High Council are not stated, but he was removed from that office and began associating with others who had also been objected to at that conference.

Martin thus aligned with a group led by Warren Parrish that believed Joseph had become a fallen prophet and sought to restore the “old standard” in the Church. When Joseph left Kirtland in November 1837, Parrish and his followers attempted to seize control of the temple and establish a new “Church of Christ.”13 Martin’s involvement in these events is not clear, but he was considered a leader among the dissenters by John Smith, and these events no doubt led directly to the “mighty pruning” that resulted in Martin and many others being “cut off … from the Church.”14

The Why

After having sacrificed so much—financially and otherwise—over the previous decade,15 Martin evidently had become frustrated with the monetary policy propagated in Kirtland. As a financially savvy member of the Church, Martin perhaps resented that he had not been consulted on how to address Kirtland’s economic problems. Brigham Young retrospectively recalled that Martin “felt greatly disappointed” at not being called to higher leadership positions.16 Martin allowed these frustrations and disagreements to fester and drive a wedge between himself and his long-time friend and prophet Joseph Smith and other leaders.

In this light, it seems likely that what attracted him to the dissidents’ cause was their willingness to give him a prominent leadership role within their new organization.17 As Parrish and his followers continued to reformulate their doctrines, however, Martin quickly found himself at odds with them over the Book of Mormon. After claiming control of the Kirtland temple, the dissenters held a meeting there in March 1838. Some of them “renounced the Book of Mormon” on top of their previous complaints about the leadership of by Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon.18

For Martin, this was a bridge too far. After those renouncing the Book of Mormon had spoken at that watershed meeting, “M[artin] Harris arose & said he was sorry for any man who rejected the Book of Mormon for he knew it was true.”19 Martin thus parted ways with the “Parrish Party” and spent the next several decades largely isolated from fellow Book of Mormon believers, though his testimony never diminished. In May 1838, for example, Caroline Barnes Crosby remembered Martin being “at variance with Joseph,” but, “Notwithstanding he bore his testimony to the book of Mormon in the strongest terms.”20

Given Martin’s deep feelings of frustration and resentment at this time, his refusal to abandon the Book of Mormon proves particularly significant. As Richard Lloyd Anderson has concluded:

Martin Harris also felt strong resentment against Church leaders, in large part stemming from the blow to his ego in never being given a major office. If such thinking is obviously immature, it was nevertheless real to the man who had sacrificed domestic peace, fortune, and reputation to bring about the printing of the Book of Mormon and the founding of the Church. Real or supposed rejection breeds hostility and, at its worst, retaliation. Though such feelings were clearly held, in the face of them Martin Harris insisted that the Mormon cause was founded on objective truth as he had experienced it in his vision of 1829.21

Most recently, historians Susan Easton Black and Larry C. Porter have thoroughly documented how Martin Harris remained a persistent and “uncompromising witness” of the Book of Mormon throughout his long life.22

Further Reading

Susan Easton Black and Larry C. Porter, Martin Harris: Uncompromising Witness of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2018), 255–300.

Rhett Stephen James, “Harris, Martin,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4 vols., ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1993), 2:574–576.

Richard Lloyd Anderson, Investigating the Book of Mormon Witnesses (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1981), 95–120.

- 1. Ronald W. Walker, “Martin Harris: Mormonism’s Early Convert,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 19, no. 4 (Winter 1986): 29–43.

- 2. Book of Mormon Central, “Why Was Martin Harris Needed to Pay for the Printing of the Book of Mormon? (D&C 19:26),” KnoWhy 597 (February 25, 2021).

- 3. Susan Easton Black and Larry C. Porter, Martin Harris: Uncompromising Witness of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2018), 184–188.

- 4. Black and Porter, Martin Harris, 219–277.

- 5. John and Clarissa Smith to George A. Smith, January 1, 1838, in Journal History of the Church, 1838, 2, Church History Library.

- 6. Due to this, it is ambiguous whether he actually excommunicated or not. For discussion of the different opinions and the evidence, see Black and Porter, Martin Harris, 298, 298–299 n.112.

- 7. Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did the Kirtland Safety Society Fail? (Doctrine and Covenants 64:21),” KnoWhy 604 (May 18, 2021).

- 8. Black and Porter, Martin Harris, 288.

- 9. Black and Porter, Martin Harris, 289–291.

- 10. Black and Porter, Martin Harris, 289–291.

- 11. See Rhett S. James and David H. James, “Martin Harris: The Witness,” Mormon Heritage 2 (July/August 1995): 33; Rhett Stephens James, The Man Who Knew: Dramatic Biography on Martin Harris (Cache Valley, UT: Martin Harris Pageant Committee, 1983), 167 nn.309–311.

- 12. Black and Porter, Martin Harris, 294–295.

- 13. Black and Porter, Martin Harris, 295.

- 14. John and Clarissa Smith to George A. Smith, January 1, 1838.

- 15. Martin began supporting Joseph Smith in late 1827.

- 16. William Harrison Homer, “The Passing of Martin Harris,” Improvement Era 29, no. 5 (March 1926): 471.

- 17. Martin’s standing in the off-shoot group is evident in his appointment as one of the “trustees” of the new Church. See Black and Porter, Martin Harris, 302–303.

- 18. Stephen Burnett to Lyman E. Johnson, 15 April 1838. Burnett’s justification for renouncing the Book of Mormon was that Martin Harris allegedly claimed he had not seen the plates, except “in vision or imagination.” Critics today frequently latch onto Burnett’s claim uncritically, failing to recognize that the real significance in these events is seen in the fact that Martin felt compelled to break away from this faction once they first began renouncing the Book of Mormon—undercutting any claim that it was on the grounds of his testimony that they had done so. Thus, Burnett and others had evidently misunderstood Martin’s words. See Black and Porter, Martin Harris, 308–310. See also Richard Lloyd Anderson, Investigating the Book of Mormon Witnesses (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1981), 155–157; Steven C. Harper, “The Eleven Witnesses,” in The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Religious Studies Center, 2015), 124–126.

- 19. Burnett to Johnson. See also George A. Smith to Josiah Flemming, March 30, 1838, “Last Sabbath a division arose among the Parrish party about the Book of Mormon, John F. Boyington, Warren Parrish, Luke S. Johnson and others said it was nonsense. Martin Harris then bore testimony of its truth and said all would be damned, if they rejected it.”

- 20. Caroline Barnes Crosby, Journal, 1807–1857, in Edward Leo Lyman, Susan Ward Payne, and S. George Ellsworth, eds., No Place to Call Home: The 1807–1857 Life Writings of Caroline Barnes Crosby (Logan, UT: Utah State University, 2005), 50.

- 21. Richard Lloyd Anderson, Investigating the Book of Mormon Witnesses (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1981), 111.

- 22. See Black and Porter, Martin Harris. For a collection of 25 testimonies borne by Martin Harris, see John W. Welch, ed., Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestations, 1820 to 1844, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Studies, 2017), 132–141.

Continue reading at the original source →