In January, Joe Lordan, the most influential coach in my life, passed away at age 88. Because of COVID-19 restrictions, his memorial service could not be held until July 24. My wife and I are making the journey from Utah to Fairfax, California, to join with Joe’s family members and friends to remember and honor him.

Joe Lordan was one of those good men who quietly protected and served his community as a cop and a coach. His obituary mentions that for three decades he coached baseball and basketball and served as a San Francisco police officer. Joe influenced hundreds, perhaps thousands, of boys and young men for good.

Since his passing, I have been thinking about him and his wife Joan and my experience on our Fairfax Shell team during the summer of 1971 when I was 12. I would like to honor him publicly by reflecting on ways that he and the two men who coached with him, Tony Damato and Manny Berretta, made a difference in the lives of the boys they coached. I connect my personal experiences with broader ideas around how coaches can establish and nourish a meaningful community, what I call a close community.

(1971 Fairfax Shell team. L-R back row, coaches, Tony Damato, Joe Lordan, and Manny Barretta)

Coaches as Creators of Close Communities

When we speak of communities, we often refer to bigger, broader entities such as towns and cities or communities based on shared religious, ethnic, linguistic, or cultural connections. In this essay, I am speaking more here about smaller, closer communities such as teams, families, congregations, or coworkers.

For some time, concerns have been expressed that Americans are less likely to be engaged in their local communities and that this negatively affects children, youth, and adults. Americans have become cynical about a wide range of social and political institutions.

The great sociologist, Robert Putnam, in his classic book Bowling Alone, demonstrates the trend toward individualism and in his new book, The Upswing, argues that we may be on the way back to building stronger communities and institutions. Yuval Levin’s The Fractured Republic argues that Americans should emphasize the middle levels of society such as families and communities. In his new book, A Time to Build, he argues that we are in a social crisis that can only be addressed if Americans move forward together in building up and strengthening families, communities, and schools. Concerns have been expressed that Americans are less likely to be engaged in their local communities.

Based on my experience with Coach Joe Lordan, here are some thoughts about how coaches can create a meaningful close community: encouraging others, helping each person feel they belong, the power of place, and being consistently present.

Encouraging Others

“Can of corn, Dave. Can of corn.”

Joe said those words to me many times during the two years he was my Little League baseball coach (1970-1971). My abiding memory of Coach Joe is of him, standing by the dugout, speaking these and other encouraging and calming words as I stepped up to the plate in a pressure situation or as I stepped up to the pitcher’s mound to face a good hitter with the game on the line.

Hearing a respected man calmly speak encouraging words in a pressure situation was a blessing. In traditional baseball parlance, “can of corn” means something that is easy. It is like saying, “No problem” or “You got this.” The phrase comes from the early 20th century when grocers used a long-hooked stick to pull cans of corn off a high shelf and catch them in their aprons. When Coach said, “Can of corn,” it meant he believed in me. Because I believed in him, I could believe in myself. When Coach Joe would say this to me it had a calming effect. It reduced some of the anxiety of the game situation I was facing.

I don’t know how many times he used that phrase. Many dozens I expect. It was often enough, and it meant enough, that I still can hear him saying it 50 years later. When I face some personal or professional challenge, I can gain perspective and confidence by thinking, “Can of corn, Dave. Can of corn.”

Help Each Person Feel They Belong

In my childhood, I often felt like an outsider. I was an Episcopalian in the midst of mostly Catholic classmates and friends. I felt like an outsider on the St. Rita team on the Catholic Youth Organization. I even wore a St. Christopher medal to try to fit in.

I grew up living in downtown Fairfax but in 5th grade, we moved to the apartments in the Oak Manor neighborhood. My parents later rented a home across the street from the Oak Manor School baseball field for a year or so. As a result, I felt like we really didn’t belong in Oak Manor. We were just renters.

So, it was no small thing for me that Joe and Joan Lordan worked hard to make all of us on the team feel welcome and to enjoy a strong sense of identity. They welcomed us to their home for swimming parties. They treated each player like we really mattered to them and to the team.

A cool uniform helps the team have a sense of personal identity and a broader identity as a team member. Our coaches painted our helmets purple and gold. To help us feel part of something bigger than ourselves and to be united, Joan sewed the letters “FS” (Fairfax Shell) on the front of our hats and sewed the letters of our names on the back of our jerseys.

Long before it was common for parents to bring snacks to sporting events, Joan Lordan brought us homemade brownies, made from scratch, and fresh-squeezed lemonade to every practice and every game. While the rules of the Fairfax Little League said you couldn’t give out special awards or trophies, Joe, Tony, and Manny hosted an end-of-season banquet at their home and gave out personalized trophies.

The Power of Place

It is difficult to create a meaningful close community without a shared place. The film, Field of Dreams, captures the magical—even mystical—power of a baseball field to unite generations, to elicit lasting memories and nostalgic feelings, and to unite communities. The film, The Sandlot, also gives a sense of the power of a ball field to create a close community.

In Fairfax, the place where our close community was established and nurtured was Central Field. In those days, for me, baseball was a religion and Central Field was our cathedral. That field was sacred ground for me and many others back when baseball was king. It takes a village to make a baseball game.

Interestingly, around the same years I played Little League baseball, Central Field also hosted a couple of very interesting softball games. One was a game that my dad played in. In an effort to build goodwill, someone organized a game between the Hippies and The Pigs (Fairfax Police Officers). “Pigs” was the derogatory term used by hippies for police officers. The other was a mid-1960s softball game between the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane (see footage in a video about the Dead’s song “Ripple”).

In my childhood, the two most important men in my life were my dad, Mel Dollahite, and my Little League baseball coach, Joe Lordan. They had important things in common. Both served in the military (Joe in the Air Force, Mel in the Naval Reserves); both were respected police officers (Joe, a deputy chief in San Francisco, Mel, a sergeant in Fairfax); both were churchgoers (Joe at St. Rita Catholic Church in Fairfax, Mel at Holy Innocents Episcopal Church in Larkspur); and both were quiet, calm, humble men.

My abiding childhood memories of them involve their presence at Central Field in Fairfax (aka Contratti Park) during our ball games. Seeing our coaches Joe, Tony, and Manny standing near the fence of the dugout cheering and coaching us was always an uplift. When my dad was on duty, in order to see me play, he drove his squad car onto the hill overlooking the ball field by the Fairfax Pavilion. At some point during the game, often when I was pitching, someone would say, “Dave, your dad’s here,” while pointing to center field. I would turn around and see my dad, in uniform, leaning against the police car smoking his pipe and watching.

As a 12-year-old in the tumultuous early 1970s, it was great to have an angel in the outfield and a few near the dugout. In some ways, a baseball field was the perfect place to teach the importance of boundaries, rules, roles, strategy, tradition, and the importance of journeying out but also coming home.

Coach Joe Heading Home

So beloved were Joe, Joan, Tony, and Manny, and so close the bonds they forged among us kids, that, in 2001, the 30th anniversary of that first championship, our second baseman, Doug MacLean, organized a reunion of that team to honor them. We gathered to reminisce and to share our deep appreciation for the close community they created for us. It was great to see my old coaches and many old teammates and celebrate those wonderful times together.

The last time I was able to spend time with Joe and Joan was in August of 2017 when my wife and I came to Fairfax for my 40th high school reunion. We went with Doug MacLean to visit Joe and Joan and reminisced about our shared passion—baseball. Joan even made her famous brownies and lemonade. On the walls of their home are pictures of all the teams Joe has coached over three decades. Every one of those kids would say they won the coaching lottery.

Knowing the kind of man Joe Lordan was, the kind of life he lived, and the number of people he influenced for good, if I were able to be there when he steps up to the Pearly Gates to face Saint Peter, I would say, “Can of corn, Joe. Can of corn.”

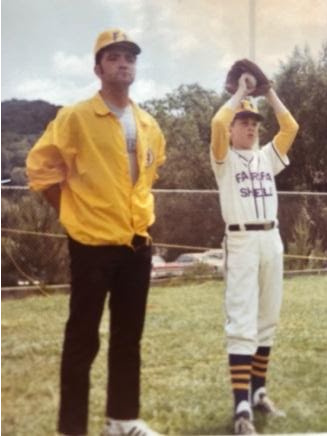

(Dave at bat with coaches Joe, Tony, and Manny standing at 3rd base dugout)

(Dave getting some pitching advice from Coach Tony Damato)

The post Remembering Coach Joe Lordan appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →