Post 1 | Post 2 | Post 3 | Post 4 | Post 5 | Post 6 | Post 7 | Post 8 | Post 9

(Post 9 of 9)

by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw

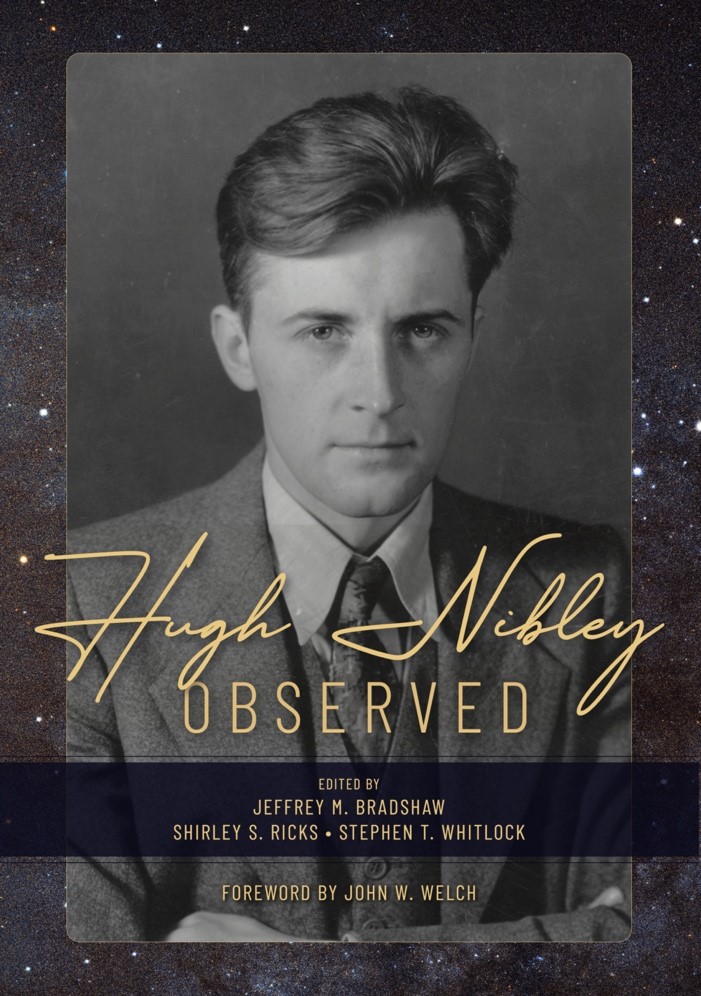

This is the ninth and last blog post published in honor of the life and work of Hugh Nibley (1910–2005). The series is in honor of the new, landmark book, Hugh Nibley Observed, available in softcover, hardback, digital, and audio editions. As in previous weeks, our post is accompanied by interviews and insights in pdf, audio, and video formats. (See the links at the end of this post.)

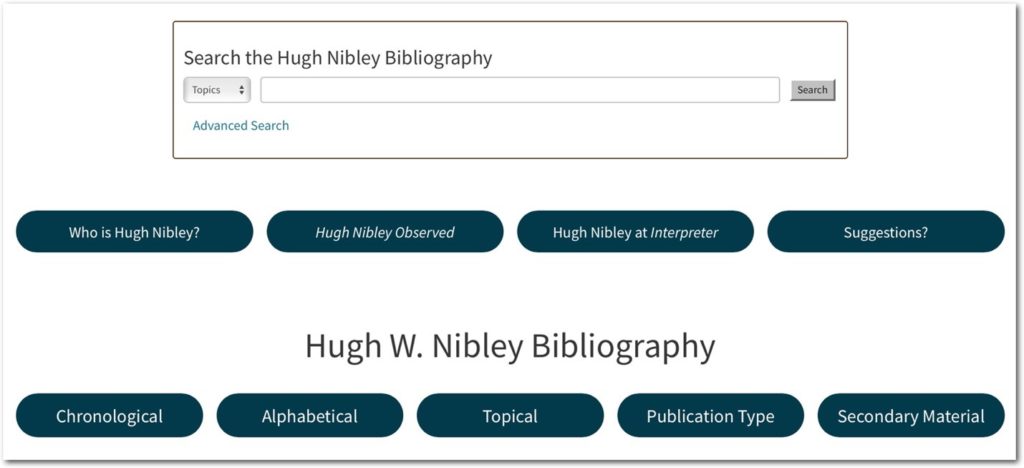

The “Complete Bibliography of Hugh Nibley” (CBHN)

The occasion for this final post is the public launch of the “Complete Bibliography of Hugh Nibley,” or CBHN, a collaboration of the Interpreter Foundation and Book of Mormon Central. The name is an evident play on the “Collected Works of Hugh Nibley” (CWHN), the magnificent corpus of nineteen published volumes of Nibley’s writings.

This online resource is freely accessible at https://interpreterfoundation.org/bibliographies/hugh-w-nibley/.

The use of the word “complete” is, of course, aspirational rather than a reality—it will be yet a while before we will be in a position to declare that the collection is as complete as we can make it. However, as of the first week in August 2021, the scope contents of the bibliography is already impressive: it contains over 1400 different references to published and unpublished writings by Hugh Nibley and others, many with freely downloadable content and others with links to bookstores where physical items can be purchased. As of this writing, we already have hundreds of additional references with pdf, video, and audio files that will be added in the near future. Please excuse our growing pains as the software and content are gradually improved.

In addition to the bibliography, a variety of resources (blogs, videos, podcasts) designed as an easy introduction to the life and works of Hugh Nibley, along with details on the “Hugh Nibley Observed” book (e.g., descriptions, reviews, purchase information), are available at the link shown above.

What Would You Do with a Thousand Years To Do Whatever You Wanted?

I asked them … to assume that they had been guaranteed a thousand uninterrupted years of life here on earth, with all their wants and needs adequately funded: How would you plan to spend the rest of your lives here? I explained that this is not a hypothetical proposition, since this is the very situation the Gospel puts us in. Whether we want to or not, we are doomed to live forever — even the wicked — for “they cannot die.”[3] In accepting the Gospel, we are already launched into our eternal program. … We are taught to think of ourselves here and now as living in eternity, and how can it be otherwise, since the contracts we make and the rules we live by are expressly “for time and eternity”?

So I asked them, “How are you going to get started on that thousand-year introduction to a timeless existence?” … Here are some typical answers:

Overwhelmed by the proposition … [I] would have to refuse it. …

First I would go crazy, … then I would be bored after 100 years. …

I would not want to live here that long. I would make long-term investments in the money markets, … would complete my education in business, get an MBA, would find a part-time job and teach my children the value of work. …

It’s not a nice question, the pressure would be too great from people who would like money from me. How should I pay tithing on it? How would I use all that money? [For this person[, notes Nibley,] the whole question is an economic one.]

I would spend my time in recreation with some serious moments. For a sense of success, I might build or write something.

I don’t know if I would want a thousand years. … Travel, study, and teach.

Could be a blessing or a cursing; I would excel in athletics and general education, would procrastinate a good deal, live in the style of the well-to-do, … shopping, camping, dancing. …

I could do nearly everything there was to do several times over. Perform service and drive a Porsche 911. …

I would turn it down. This life is okay, but I am anxious to get on with my progression in the hereafter. [Doing what, I might ask? This is your progression into the hereafter!]

And so it goes. No wonder [Shakespeare’s] Hamlet finds a world of such people “weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable.”[4] “What is a man” he asks, “if his chief good and market of his time be but to sleep and feed? A beast, no more.”[5] …

President Harold B. Lee once … told us how at a meeting of [a stake] high council the question of the hereafter came up. One of the group, an undertaker, humorously noted that he would have to change his profession. Upon this, a dentist chimed in and confessed that he was in the same case; next an insurance man … admitted that there would not be much call for his talents, and then a used car salesman saw only limited prospects for his own business, as did the … real estate [agent] in the group, and so it went. If these men were not to dedicate themselves to making money, what would they do? A thousand years of guaranteed livelihood rule out the necessity of almost all the professions, businesses, and industries that thrive on the defects of our bodies and the insecurity of our minds.[9]

What would I do with a thousand years of uninterrupted time? Well, among other things, I would certainly start to explore the rich library of Hugh Nibley’s writings more thoroughly, especially now that they have been made so much more easily available through the CBHN. I would be able to spend more time learning about the things of eternity.

But what should I be doing in the meantime? Mustn’t we instead fully live in the world of the present? In answer to this question, Nibley’s response is short and direct:[10]

Must we? Most people in the past have got along without the institutions which we think, for the moment, indispensable. And we are expressly commanded to get out of that business, says Brigham Young:[11]

No one supposes for one moment that in heaven the adding railroads and factories, taking advantage one of another, gathering up the substance there is in heaven to aggrandize themselves, and that they live on the same principle that we are in the habit of doing. … No sectarian Christian in the world believes this; they believe that the inhabitants of heaven live as a family, that their faith, interests, and pursuits have one end to view—the glory of God and their own salvation, that they may receive more and more. … We all believe this, and suppose we get to work and imitate them as far as we can?

It is not too soon to begin right now. What are the things of eternity that we should consider even now?

***

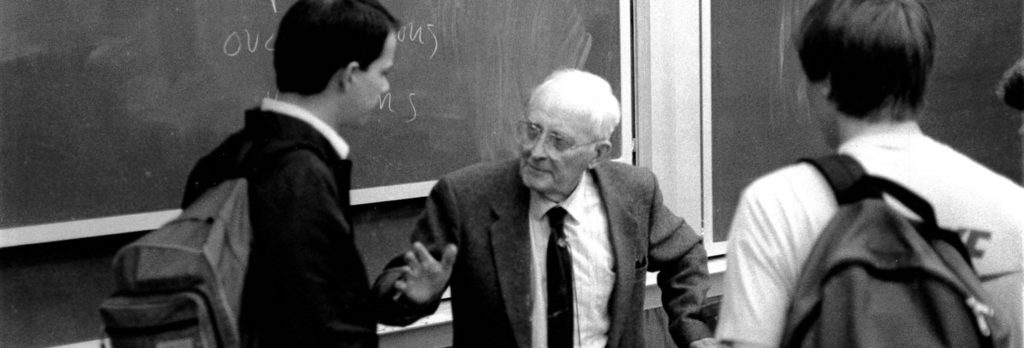

This week, we are pleased to include a video remembrance about Hugh Nibley, recounted by Rebecca Nibley, his daughter. In “Swimming with My Dad,” we learn important things about the character and family life of Hugh Nibley, including the answer to his daughter’s question, “Daddy, do you ever pray when you are alone?”

References

Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. Liverpool and London, England: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1853-1886. Reprint, Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Maxwell, Neal A. 1981. “Grounded, rooted, established, settled (Ephesians 3:17, 1 Peter 5:10) (BYU Address, 15 September 1981).” In The Inexhaustible Gospel: A Retrospective of Twenty-One Firesides and Devotionals at Brigham Young University 1974-2004, 109-21. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 2004.

Nibley, Hugh W. “The Roman games as a survival of an archaic year-cult.” Doctoral Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 1939.

———. “But what kind of work?” In Approaching Zion, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 9, 252-89. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

———. 1951. “Sparsiones.” In The Ancient State, edited by Donald W. Parry and Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 10, 148-94. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1991.

———. 1956. “Victoriosa Loquacitas: The Rise of Rhetoric and the Decline of Everything Else.” In The Ancient State: The Rulers and the Ruled, edited by Donald W. Parry and Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 10, 243-86. Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1991. Reprint, Western Speech 20 (Spring 1956), 47-82.

———. 1975. “Zeal without knowledge.” In Approaching Zion, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 9, 63-84. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

Shakespeare, William. 1600. “The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark.” In The Riverside Shakespeare, edited by G. Blakemore Evans, 1135-97. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin Company, 1974.

Notes

[1] http://mi.byu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Nibley-1.jpg.

[2] H. W. Nibley, But What Kind, pp. 257-260.

[3] Alma 12:18.

[4] W. Shakespeare, Hamlet, 1:2:133, p. 1145.

[5] Ibid., 4:4:33-35, p. 1172.

[6] Licensed from Shutterstock, still image from v7983493.mov.

[7] Regarding theatromania, see H. W. Nibley, Victoriosa Loquacitas; H. W. Nibley, Sparsiones; H. W. Nibley, Roman Games.

[8] http://www.peoplenotary.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/06/running-businessman.jpg (accessed 3 January 2016).

[9] Elder Neal A. Maxwell perceptively commented on this topic (N. A. Maxwell, Grounded, pp. 111-112, 118-119):

It is especially helpful to remember also that the temptations and challenges we face are common to man (see 1 Corinthians 10:13), yet we must respond uncommonly. It is also useful to ponder the fact that, along with even the Savior himself, we are to experience certain things “according to the flesh” (Alma 7:12) and to learn “in process of time” (Moses 7:21). Built, therefore, into the seemingly ordinary experiences of life are opportunities for us to acquire such eternal attributes as love, mercy, meekness, patience, and submissiveness and to develop and sharpen such skills as how to communicate, motivate, delegate, and manage our time and talents and our thoughts in accordance with eternal priorities. These attributes and skills are portable; they are never obsolete and will be much needed in the next world.

How often have you and I really pondered just what it is, therefore, that will rise with us in the resurrection? Our intelligence will rise with us, meaning not simply our I.Q., but our capacity to receive and to apply truth. Our talents, attributes, and skills will rise with us, certainly also our capacity to learn, our degree of self-discipline, and our capacity to work. Note that I said “our capacity to work” because the precise form of our work here may have no counterpart there, but the capacity to work will never be obsolete. To be sure, we cannot, while here, entirely avoid contact with the obsolescent and the irrelevant. It is all around us. But one can be around irrelevancy without becoming attached to it, and certainly we should not become preoccupied with obsolete things.

By these remarks I do not intend to create discontent with the paraphernalia of this probationary estate, but it is a grave error to mistake the scenery and the props for the real drama which is underway. Nor do I wish to bear down too much on the fact that certain mortal vocations will be irrelevant in the next world. A mortician does useful work here, especially if it is done with excellence, compassion, and reverence for life. Whatever our vocation, we should be sweetened, not hardened. Keeping our sense of proportion whatever we do, keeping our precious perspective wherever we are, and keeping the commandments however we are tested reflect being settled, rooted, and grounded in our discipleship. …

[H]ow we utilize the seemingly ordinary experiences of our life and how well we keep the commandments are true tests of our performance in this second estate. One can, while in the employ of a railroad company, learn something of patience while struggling to keep the train schedule meticulously up to date. But the patience will long outlast the printed train schedule. A discovering scientist may augment his awe and meekness before his Creator because of the breathtaking order in the universe even if his new discoveries erelong are swallowed up in even more immense discoveries.

But it is also true that routine may cause a gravedigger to become indifferent to the sorrows of the bereaved gathered about those fresh mounds of earth. The gravedigger may even become cynical about the resurrection which one day will empty all those graves. A marriage counselor can become encrusted with a protective layer of clinical indifference brought on by the routine and incessant nature of his chores. If so, his techniques will never compensate for his lack of caring. A civil servant who has forgotten how to be civil may have some sway now in the procurement division of a vast governmental direction, but he is headed in just the opposite developmental direction needed for sway in the next world.

On the other hand, one who listens more and more effectively to others with a genuine desire to understand and to help, if not always to agree, will have no regrets later on. Such an individual may occasionally run out of time here, but he is fitting himself for eternity. Love and patience are never wasted; they only appear to be. The devoted wife and mother who is a quiet but effective neighbor but whose obituary is noticed by a comparative few may well have laid up precious little here in the current coin-of-the-realm, recognition, yet rising with her in the resurrection will be relevant attributes and skills honed and refined in family and neighborhood life. Contrariwise, the civic leader whose thirst for recognition causes him to do things to be seen of men has his reward. He too will receive the gift of immortality during which expanse he can work on meekness and humility.

[10] H. W. Nibley, Zeal, p. 79.

[11] Brigham Young, in JD, JD, 17:117–18.

Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (PhD, cognitive science, University of Washington) is a senior research scientist at the Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition (IHMC) in Pensacola, Florida (www.ihmc.us/groups/jbradshaw; en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeffrey_M._Bradshaw). His professional writings have explored a wide range of topics in human and machine intelligence (www.jeffreymbradshaw.net). Jeff has written studies on temple themes in the scriptures and the ancient Near East as well as commentaries on the Book of Moses and Genesis 1–11 (www.TempleThemes.net). Jeff was a missionary in France and Belgium from 1975 to 1977, and his family has returned twice to live in France. He is currently a vice president of the Interpreter Foundation, a service missionary for the Department of Church History with a focus on Africa, and a temple ordinance worker in the Meridian Idaho Temple. Jeff and his wife, Kathleen, are the parents of four children and fifteen grandchildren. From 2016 to 2019, they served missions in the Democratic Republic of Congo Kinshasa Mission office and the Kinshasa Democratic Republic of the Congo Temple. They now live in Nampa, Idaho.

Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (PhD, cognitive science, University of Washington) is a senior research scientist at the Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition (IHMC) in Pensacola, Florida (www.ihmc.us/groups/jbradshaw; en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeffrey_M._Bradshaw). His professional writings have explored a wide range of topics in human and machine intelligence (www.jeffreymbradshaw.net). Jeff has written studies on temple themes in the scriptures and the ancient Near East as well as commentaries on the Book of Moses and Genesis 1–11 (www.TempleThemes.net). Jeff was a missionary in France and Belgium from 1975 to 1977, and his family has returned twice to live in France. He is currently a vice president of the Interpreter Foundation, a service missionary for the Department of Church History with a focus on Africa, and a temple ordinance worker in the Meridian Idaho Temple. Jeff and his wife, Kathleen, are the parents of four children and fifteen grandchildren. From 2016 to 2019, they served missions in the Democratic Republic of Congo Kinshasa Mission office and the Kinshasa Democratic Republic of the Congo Temple. They now live in Nampa, Idaho.

The post “What Would You Do with a Thousand Years To Do Whatever You Wanted?”: Contemplating the “Complete Bibliography of Hugh Nibley” (CBHN) appeared first on FAIR.

Continue reading at the original source →