A common trend in contemporary Western thought is to deny the reality of demonic evil. This trend arises from a combination of dismissal of scriptural accounts of demonic possession; lack of personal experience; and a general tendency in the West to reinterpret supernatural phenomena through a scientist or naturalist worldview. This trend to disbelief was present even among Latter-day Saints from the early days of the restoration; Jedediah M. Grant lamented in an 1854 address in the Salt Lake Tabernacle that “I am aware that even some of the Latter-day Saints are slow to believe in relation to the power of Lucifer, the son of the morning, who was thrust from the heavens to the earth; and they have been slow to believe in relation to the spirits that are associated with him…”

Latter-day Saints have a unique perspective on demonic evil; restoration scripture tells us that in our day, one of Satan’s strategies will be to reason himself out of our consciousness and deny his own existence. But our missionaries sometimes serve in parts of the world where this strategy is not pervasive, where demonic possession and related phenomena are open and observable. For Latter-day Saint missionaries who served in Brazil and neighboring areas, the Netflix series John of God is a reminder of the religion called Espiritismo, or “Spiritism,” that is common in those regions, and which actively welcomes the “receiving of spirits,” a euphemism for possession.

We are wisely counseled to limit our discussions of possession and other demonic phenomena. But having seen the demonic in its more open manifestations, many of us find it hard to view Satan-denial as anything more than wishful thinking.

Modern Western Satan-denial is informed by critical biblical scholarship, which holds that before the Babylonian exile Satan existed in Israelite consciousness more on a conceptual level than as a commonly-known figure of sacred history. Scholars point to, among other things, the animalian serpent figure in Genesis and the obviously literary portrayal of the satan-figure who carries on in dialogue with God in the book of Job, as evidence for this disjointed Satan-concept. Hell is not merely a place where damned souls go after this life to stew in regret; rather, it is a state of heart and mind that is experienced here in the present.

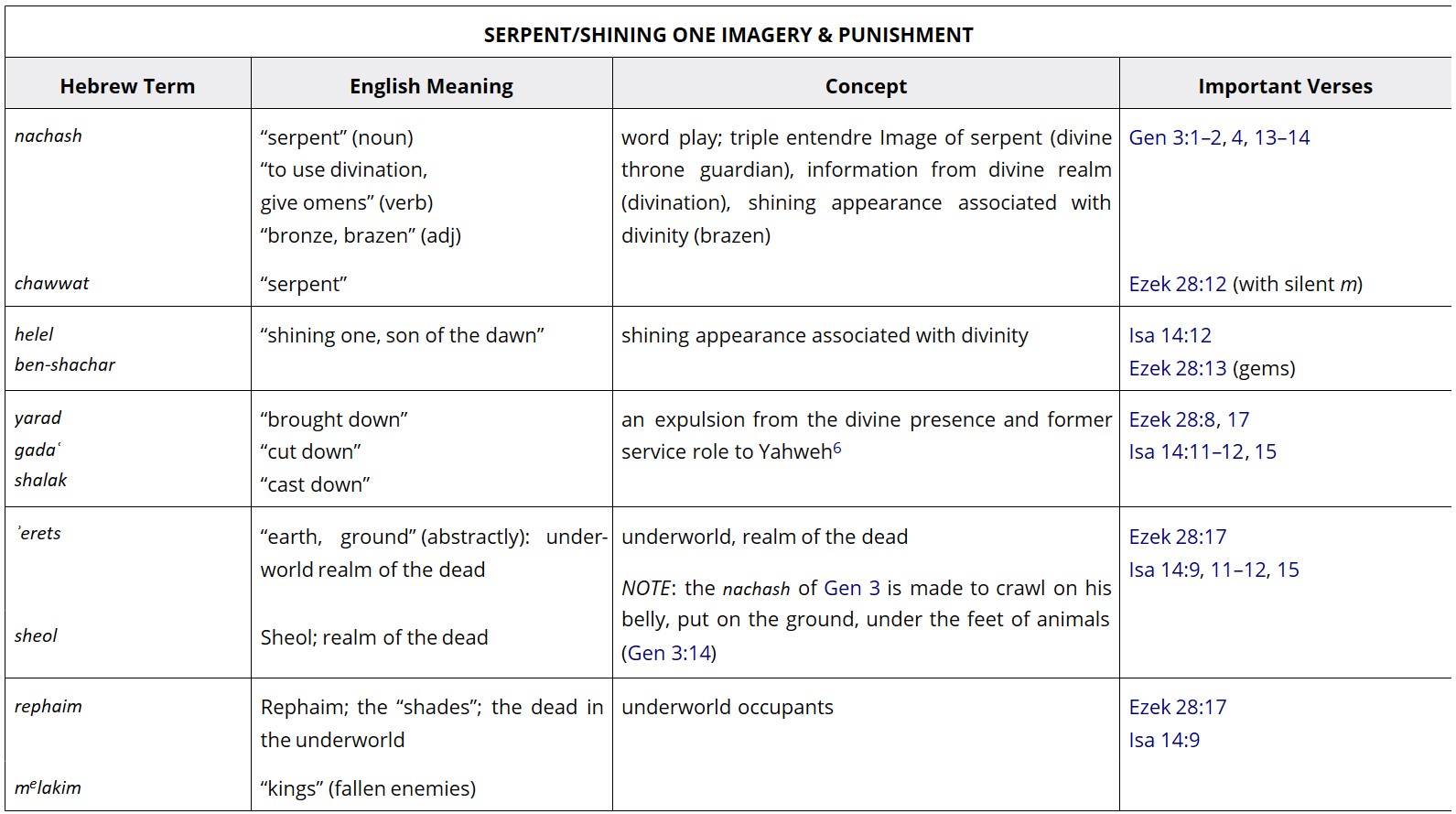

One of the passages that Lehi read was likely Isaiah 14, which is a composite text of a prophetic taunt that mocks the humiliating fall of arrogant powers (How art thou fallen … how art thou cut down to the ground …). Lest we moderns characterize Isaiah’s taunt as purely political in nature, believing scholar Michael Heiser points to the shared genre between Isaiah 14 and Ezekiel 28, where the prince of Tyre is mocked in similar form and language. But in his analysis, Heiser also demonstrates that Ezekiel uses Hebrew terms and imagery found in Genesis 3, alluding to the serpent in Eden, to portray the prince of Tyre as fallen from high status.

Table from Heiser, The Unseen Realm

By the time of the New Testament, Jewish notions of Satan and demonology had congealed into a more developed system that explained the phenomena of possession we see in the gospels. When Jesus claimed, “I beheld Satan as lightning fall from heaven,” His remark was not received with the puzzlement that we see in His disciples’ reactions to His other statements; they likely understood it in the context of the fall-from-on-high narratives of Isaiah 14 and Ezekiel 28. Later, John the Revelator would expound on this story in his portrayal of the accuser-dragon in Revelation 12 who is cast down and strives in vain to overwhelm “our brothers and sisters” and the church by vomiting a flood of accusation.

Joseph Smith taught that if we do not get knowledge, we “… will be brought into captivity by some evil power in the other world, as evil spirits will have more knowledge, and consequently more power than many men who are on the earth.” Brigham Young also famously encouraged the saints to become knowledgeable about evil. In that spirit, Michael Heiser’s scholarship on demonology is an important corrective to ideas about evil that have become common in Christianity over the centuries: most importantly, the simplistic view that Satan’s purposes are to tempt humanity to break commandments and lead us to a post-mortal destination called hell. When Christians refuse to dig any deeper than this, the result is a concept of Satan and evil that is easily outgrown and abandoned. Heiser’s scholarship is well supplemented by the work of C.S. Lewis, whose book The Screwtape Letters offers an imaginary but accurate glimpse into demonic thinking.

Lewis’ book The Great Divorce is likewise an excellent exploration of hell that offers crucial insights: hell is not merely a place where damned souls go after this life to stew in regret; rather, it is a state of heart and mind that is experienced here in the present and into eternity, as long as we desire it.

But many core insights into the nature of demonic evil are in the gospels, and they come straight from the mouths of Satan and his demonic followers themselves. The temptations of Jesus are referenced in three of the gospels, with specificity in Matthew and Luke. There the gospel writers recall Satan’s visit to Jesus in the wilderness and his suggestions that Jesus answer normal human desires and cravings: bread for his physical hunger; a dramatic angelic rescue for recognition and validation; and supreme political power that would allow for him to impose His will upon the world: in a word, control. Satan does not encourage Jesus to sin against the law; his suggestions are for Jesus to answer common longings, and they offer a foundational insight into the nature of hell: hell is needy.

With the three temptations of Christ, we learn the underlying motives of sin. In his suggestions to Jesus, Satan reveals that his own motivations are largely what psychologists call projection: assuming that other people share our thinking and desires. Satan projects onto Jesus his own insatiable appetite for recognition and his fixation on power and control; Jesus then counters each suggestion with a statement of His own real motivation, a love of God. It is important to reiterate that here Satan does not try to entice Jesus to break God’s law—he is confident that if their interaction in the wilderness can leave Jesus craving, insecure, and power-obsessed, then violations of God’s law and exploitation of other people will naturally follow.

My own view is that Jesus’ temptation experience in the wilderness specifically led to much of the material that comprises the Sermon on the Mount. There Jesus counters Satan’s three suggestions with calls for his disciples to embrace a mindset of faith and abundance:

Because of this, I say to you, do not worry about your life, about what to eat and drink, nor for your body and what you wear. Is not life more than food and the body more than clothing? Look at the birds of heaven. They do not sow seeds or reap crops or gather the harvest into storehouses, but your Father in heaven cares for them. Are you not greater than they are? Who is able to add one measure to his height by worrying? And why do you worry about clothing? Think about the lilies of the field, how they grow, but they do not work or spin. But I say to you that Solomon in all his glory was not dressed like one of them. If God so clothes the grass of the field that today is alive and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, how much more will he clothe you of little faith? Do not worry, saying, ‘What will we eat, what will we drink, or what will we wear?’ The Gentiles seek after all these things, but your Father in heaven knows that you need all these things. Seek first the kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you. Do not worry about tomorrow, because tomorrow can worry for itself. Today’s evil is sufficient for today (Wayment translation).

These passages provide the doctrinal basis for the social gospel, the objective of which is not to advance modern visions of utopia, but rather to enable the development of an emotional and spiritual baseline of sufficiency instead of a constant fixation on unmet basic needs. This baseline articulated by Jesus is essential for real human connection; without it, the soul tends to view every other soul not as they really are, but only in terms of their ability to either satisfy or validate our needs and cravings.

The neediness that characterizes hell is further shown in gospel narratives of Jesus’ encounters with demons: as He approaches, they cry out and wail over the clash between their desire to continue exploiting people, and His desire to heal their victims. Their possession of human bodies answers a jealous craving for embodiment, one which the demons cannot satisfy honestly through a legitimate, God-ordained process.

There is a resentful question voiced by the demons, and we should examine it because it is worth understanding. In one of the confrontations, the demons cry out “What have we to do with thee?” and in another, “What have I to do with thee, Jesus, thou Son of God most high? I beseech thee, torment me not.” This is how the demons assert they should be left alone— expressing a demonic sense of entitlement, and insinuating that their possession of humans is harmless. The question what have we to do with thee contains an embedded accusation that God is being unfair.

The Book of Mormon lacks New Testament-style stories of demonic possession, but Samuel the Lamanite’s reference to demons offers a profound insight. In his warning to the wicked Nephites, he prophesies that one day they will awaken and fully recognize the influence of the demonic among them:

Behold, we are surrounded by demons, yea, we are encircled about by the angels of him who hath sought to destroy our souls. Behold, our iniquities are great. O Lord, canst thou not turn away thine anger from us? And this shall be your language in those days. But behold, your days of probation are past; ye have procrastinated the day of your salvation until it is everlastingly too late, and your destruction is made sure; yea, for ye have sought all the days of your lives for that which ye could not obtain; and ye have sought for happiness in doing iniquity, which thing is contrary to the nature of that righteousness which is in our great and Eternal Head.

Here the italicized phrases are related; as we have seen in the gospel possession accounts, the inability to find happiness in doing iniquity is the core, maddening inner conflict that fuels demonic neediness.

A modern profile of this demonic inner turmoil is Karl Marx, who was open in his admiration for demonic figures of literature and religious history. Marx’s poetry contains recurring themes of self-worship, pacts with Satan, suicide, and contempt for God. His Human Pride echoes the language of Isaiah 14 and Ezekiel 28 in its glorification of self against “giant She-Dwarf” God:

And it matters not a whit

Where the veryGod-Thought fares

On its breast will cherish it;

Soul’s own greatness is its lofty Prayer.

Soul its greatness must devour,

In its greatness must go down;

Then volcanoes seethe and roar,

And lamenting Demons gather round.

Soul, succumbing haughtily,

Raises up a throne to giant derision;

Downfall turns to Victory,

Hero’s prize is proud renunciation.

… Then the gauntlet do I fling

Scornful in the World’s wide open face.

Down the giant She-Dwarf, whimpering,

Plunges, cannot crush my happiness.

Like unto a God I dare

Through that ruined realm in triumph roam.

Every word is Deed and Fire,

And my bosom like the Maker’s own.

(italics added)

That last phrase, “my bosom like the Maker’s own,” turns projection into blasphemy, and is a typical expression of Marx’s personal loathing toward God. Marx’s statement that “the criticism of religion is the prerequisite of all criticism” relates to the demonic criticism of Christ; both Marx’s statement and the demonic “what have we to do with thee?” reflect an understanding that the story of divine redemption stands as the primary obstacle to the demonic work of chaos and horror.

More recently, in an article for First Things, Ephraim Radner discussed case studies of atheist artist Francis Bacon and also philosopher Michel Foucault, a tormented pedophile who advanced now-fashionable ideas that language and other aspects of human experience are used primarily to acquire power. Radner describes the similarities in their profiles:

… he was like Foucault, whose inner demons gave rise to an often exquisite jouissance of detailed erudition that seemed to mask the unrealized desire “to be loved.” With Foucault, the dynamic produced an entire philosophy of barely controlled (and hardly believable) “self-care,” the redoubt of those who cannot find or give the love they crave. But note well: There is nothing cynical here, for either Bacon or Foucault. We see only desperate self-protection and naive vulnerability, which Foucault’s own demise seemed to embody and Bacon’s bizarre and violent sexual life enacted.

This craving neediness of hell is contrasted with the inner peace, poise, and abundance of heaven in C.S. Lewis’ The Great Divorce. There, the dynamics of heaven and hell are dramatized as a busload of souls in hell are taken to heaven and ministered to by the heavenly souls there. The narrator is accompanied by a teacher, Scottish preacher George MacDonald, as they witness and discuss the interactions between souls. At one point, the narrator describes the emergence of a heavenly soul, a woman named Sarah Smith, who is surrounded by beings who bask in her radiant presence.

“She is one of the great ones. Ye have heard that fame in this country and fame on Earth are two quite different things.”

… “Every young man or boy that met her became her son—even if it was only the boy that brought the meat to her back door. Every girl that met her was her daughter.”

“… Every beast and bird that came near her had its place in her love. In her they became themselves. And now the abundance of life she has in Christ from the Father flows over into them.”

I looked at my Teacher in amazement.

“Yes,” he said. “It is like when you throw a stone into a pool, and the concentric waves spread out further and further. Who knows where it will end? Redeemed humanity is still young, it has hardly come to its full strength. But already there is joy enough in the little finger of a great saint such as yonder lady to waken all the dead things of the universe into life.”

As the narrator and his teacher observe, Sarah Smith encounters her emotionally needy husband who is visiting from hell. In their conversation, he wails over her acknowledgment that she loves him but does not need him. “She needs me no more—no more. No more … Would to God … I had seen her lying dead at my feet before I heard those words. Lying dead at my feet. Lying dead at my feet.” The damned souls in The Great Divorce frequently invoke love as their yearning, but it is clear that love in hell is a manipulative and needy perversion of the real thing. It is what we usually refer to as codependency, which Latter-day Saint authors Jennifer Roach and Nick Galieti describe as “a type of dysfunctional helping relationship where one person supports or enables another person’s … poor mental health, immaturity, irresponsibility, or under-achievement by removing or fixing the consequences others experience.” As with many souls of the damned in The Great Divorce, Sarah Smith’s codependent husband is looking not to be loved in any mature way; rather he is consumed with a desire to be pitied and eternally enabled (and further tormented by his wife’s refusal to indulge him). The inability to find happiness in doing iniquity is the core, maddening inner conflict that fuels demonic neediness.

The desire of hell to spread itself should be cause for concern among believers: Jesus warned about wolves in sheep’s clothing among the flock of believers, and he described them as “ravening,” which implies craving and neediness. Jesus also famously lamented that the Scribes’ and Pharisees’ misuse of religion was making their adherents into “twice the child of hell” that they were. We can surmise that most of the worst moments of religious history have in common this same departure from the true purpose of religious devotion. Even in church contexts, religion can sometimes be used not as a means of coming to know God, but instead as just another way to feed the three temptations of physical appetites, recognition, and control. Without the authentic, transformational experience of God, churches and church-going people can become just another vector for the spread of hell.

This spreading is thwarted in encounters with the spiritual abundance and poise of heaven. This is why when Jesus’ disciples lamented a failed exorcism, He told them that some demons cannot go out except through prayer and fasting, implying that exorcism is unlikely to be effective if the spiritual baseline of the exorcist matches the craving, delusional energy of the evil spirit. Jesus affirmed that there is a deep power that comes from communion with God through a life of authentic prayer, coupled with the spiritual abundance that comes as we regularly step away from our normal cravings and desires in the process of fasting. Isaiah wonderfully describes the transformative effect of true fasting: “… thou shalt be like a watered garden, and like a spring of water, whose waters fail not.” This imagery is echoed in the gospel of John, where Jesus promises the Samaritan woman at the well that those who drink of the water He offers will lose their thirst, becoming like overflowing springs of water. The gospel possession accounts demonstrate that demons find the physical presence of this quality of soul to be unbearable.

Illustrating the power of personal spiritual energy, President Henry B. Eyring shared a story in 2010, of a time when his father was hospitalized with an illness and was visited by President Spencer W. Kimball:

Once I was at the hospital bedside of my father as he seemed near death. I heard a commotion among the nurses in the hallway. Suddenly, President Spencer W. Kimball walked into the room and sat in a chair on the opposite side of the bed from me. I thought to myself, “Now here is my chance to watch and listen to a master at going to those in pain and suffering.”

President Kimball said a few words of greeting, asked my father if he had received a priesthood blessing, and then, when Dad said that he had, the prophet sat back in his chair.

I waited for a demonstration of the comforting skills I felt I lacked and so much needed. After perhaps five minutes of watching the two of them simply smiling silently at each other, I saw President Kimball rise and say, “Henry, I think I’ll go before we tire you.”

I thought I had missed the lesson, but it came later. In a quiet moment with Dad, after he recovered enough to go home, our conversation turned to the visit by President Kimball. Dad said quietly, “Of all the visits I had, that visit I had from him lifted my spirits the most.”

The ability to recognize and differentiate between people’s spiritual energy is a key to discernment, which is the essential discipline for arresting the spread of hell in our spheres of influence. The need for discernment is illustrated in a shocking moment in Netflix’s John of God where Oprah Winfrey is seen leaving the spiritist compound and commenting on the positive emotional power of her experience with a “spiritual healer” whom the series would later reveal to be an abusive monster. The discipline of discernment has many forms, and one of the most basic forms of discernment is observation. As people advocate ideas and behaviors, is their activism performed loudly and publicly in lieu of private, loving service? Does advocacy emerge from a place of frantic craving and delusion, an insistence that reality be something other than what it is? Or does it emerge from spiritual poise, from spirituality attended by transcendent peace and steady revelation? Is advocacy motivated by charity and a yearning for Christian reconciliation, or by fearful loathing of “enemies” and a fixation on power? For Latter-day Saints in particular, does an idea reflect the will of the Christ who is in communion with His prophet servants and endows them with his own spiritual energy, or does it reflect a fearful, delusional, and violent worldly vision for God’s children? All of these are relevant questions in the process of spiritual discernment. Demons are less frightening than they are pathetic.

The post Understanding Demons appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →