After a very long and extremely ugly history, antisemitism in America has been increasing tragically as Jewish people are experiencing greater levels of assaults, harassment, and vandalism. Indeed, according to the FBI, nearly 60% of hate crimes in 2020 targeted Jews. And, Bari Weiss has identified antisemitism as the result of various political and societal ideologies.

While anti-Mormonism is real, Latter-day Saints have experienced only a tiny fraction of the persecution our Jewish friends have been subjected to over their three-millennia-long history. But as members of a misunderstood minority faith, it behooves us to join in solidarity with our Jewish friends however and whenever we are able.

In times like these, I believe it is important to highlight commonalities across faith communities and respect for those of other faiths, particularly as we help each other cope with the pandemic and its aftermath, including mourning our many losses together. In both personal and professional contexts, I have been fortunate to enjoy a number of sacred experiences with Jewish friends.

In this essay, I share a few experiences my family and I have enjoyed with our Jewish friends in their worship services and holy days in California and in New England. Although these stories are spread across my life, several experiences occurred during visits to synagogues as part of research I conducted on families of various faiths (including 30 Jewish families) for the American Families of Faith project. I begin with my longest and closest relationship with a beloved Jewish person–Ann Scinski.

A Jewish Godmother

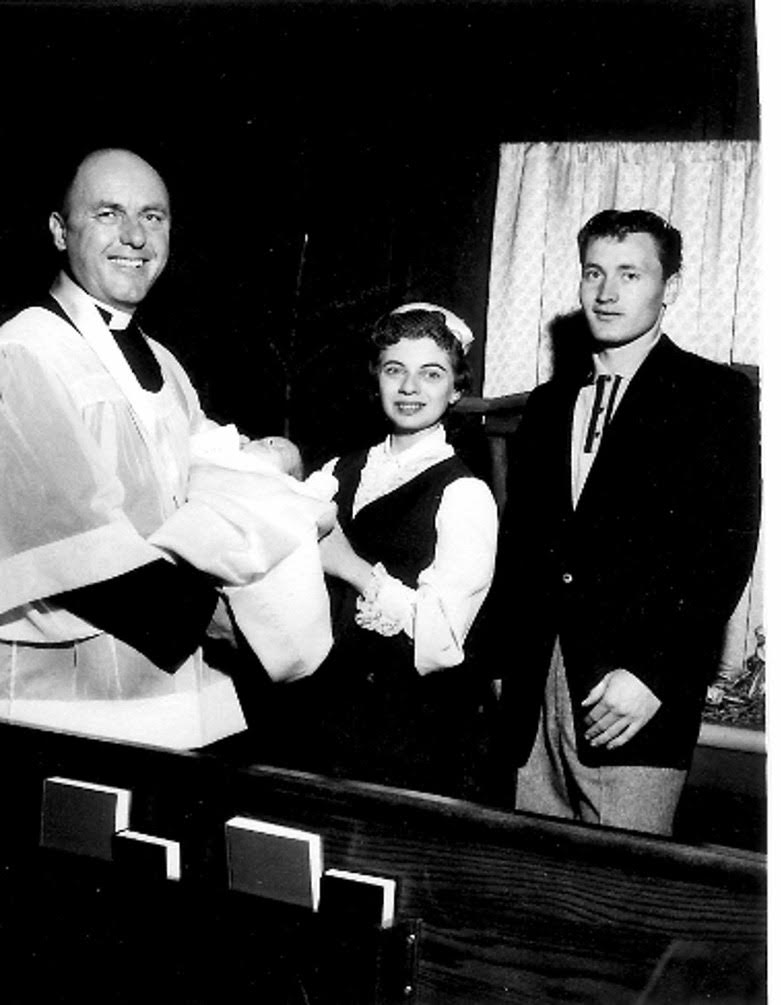

I was 19 days old when I had my Christian baptism. In attendance was my Jewish godmother, Ann. While I don’t remember this gathering, the photograph below, taken by my dad, documents it. My parents’ Episcopal priest, Father Todd Ewald, is holding me along with my godmother, Ann, and my godfather, Gene. So how did a Jewish woman come to be the godmother at my Christian baptism?

Episcopal infant baptism of David Dollahite held by Father Todd Ewald, accompanied by my Jewish Godmother Ann Scinski and Godfather Gene Dollahite

Father Ewald asked my mother who would be my godfather. She said my Uncle Gene. Father Ewald knew Gene well and was like a father to him. Gene served as a Deacon at the church and later became an Episcopal Priest. Father Ewald completely approved of Gene as my godfather.

When Father Ewald asked my mom who my godmother would be—she said her lifelong best friend, Ann. When Father Ewald asked about Ann’s religion, my mom told him she was Jewish. Father Ewald said that a Jewish woman cannot be the godmother for a Christian baptism.

Part of what it means to be a godparent is to ensure a Christian upbringing for a child in case the parents die, and my mom told Father Ewald that Ann was committed to this and if anything happened to my parents, Ann would be sure I was raised as a Christian.

Father Ewald said that Ann could not be my godmother since godparents must be baptized and confirmed Christians. Mom said that if Ann could not be my godmother, then I would not be baptized at all. Father Ewald said that perhaps in this case an exception could be made. Thus, I have a Jewish godmother.

The photo of Ann and my mom, Elizabeth, captures their lifelong friendship and attests that Ann was there for both joyous times as well as painful times.

As I grew up, my mother often expressed her profound respect for Jews and Judaism and support for Israel. When I was 19-years-old, I experienced a profound spiritual conversion to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which has only deepened the strong connection I have always felt with Judaism and the Jewish people.

Ann stayed close with my mom throughout her life, and Ann and I exchanged Christmas and Hannukah greetings. Mom told me that the day after I received my Ph.D. in family studies, she called Ann and made sure to work in the famous phrase so many Jewish mothers love to say, “My son, the doctor.” (Throughout history a disproportionate number of physicians have been Jewish since, for Jews, practicing medicine is considered a kind of religious duty.)

Ann was not only part of a sacred gathering at the beginning of my life, but she was also present with us as our family gathered at the end of Mom’s life. Ann made the journey from her home in Massachusetts to Seattle to be with my mom Elizabeth as she was in the last weeks of her battle with cancer.

Because of my mom’s relationship with Ann, I have admired Judaism and felt close to the Jewish people. This was manifest most profoundly during a sabbatical in New England along with my wife and four daughters, where I enjoyed many experiences with Jewish friends, some of which I share below.

Seven Sacred Educational Experiences with Jewish Friends

In both the Jewish and Latter-day Saint communities, religious education is considered a sacred activity. Here, I briefly touch on seven educational experiences I have enjoyed with Jewish friends.

First, in the early 1990s, when I was a new professor of family studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, I attended Friday worship services at Beth David Synagogue, a Conservative Jewish community in Greensboro. There, I took a Hebrew class.

For the next year I spent a couple of hours a week in class with our marvelous instructor, Cookie Cohen. Cookie was enthusiastic about teaching the sacred language of the Jewish people. While most of the students were Jewish adults who wanted to strengthen their command of Hebrew, Cookie warmly welcomed three Christians to the class: two Baptist older women and me, a young Latter-day Saint man.

We had a wonderful time together, and I cherish the hundreds of hours I spent studying Hebrew. I attended worship services regularly to practice what we were learning in class, and I will never forget Cookie’s kindness with us as we tried—in what I’m sure was butchered Hebrew—to learn those sacred prayers. I will also never forget the way Cookie tried to hide her smile when one of the Baptist women, in her deep Southern accent, tried to speak a Jewish blessing.

Tragically, as I recall during that year, Cookie’s son died while he was in Africa on a humanitarian mission raising money to help fight AIDS. To this day, I cannot hear the mourner’s kaddish recited without thinking of Cookie and her son.

Second, in the Spring of 2002, I enjoyed a six-month sabbatical as a visiting scholar at the Center for Research on Families at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst (UMass Amherst). While there, I sat in on two classes about Jewish family life taught by Jay Berkovitz, a Modern Orthodox professor of Judaic and Near Eastern Studies at UMass Amherst. I also spent a number of hours in conversation with Jay about Jewish family life in his office. Jay invited me to come with him to New York to visit three bastions of Jewish culture: The Jewish Theological Seminary, Union Theological Seminary, and Yeshiva University. This last university is where students take their Orthodox faith seriously and, like my own faith at BYU, boasts a capella groups that garner attention on YouTube (The Maccabeats at Yeshiva and Vocal Point and Noteworthy at BYU).

Third, during my sabbatical at UMass Amherst, Rabbi Saul Perlmutter at the UMass Amherst Hillel, the Jewish Student association on campus, heard that I was a visiting scholar at the university. He invited me to speak to his students. When the evening arrived, there were about 30 students gathered in a circle at the Hillel House to hear what a Latter-day Saint social scientist had to say about religion and family life. Since religious education and learning are important matters for Jews, I considered this a sacred opportunity.

Rabbi Perlmutter said I could speak about any topic I wished. I chose to talk about the power of Jewish traditions in strengthening marriage and family life. I spoke about my experiences with Jewish families I had interviewed and how much I admired their family-centered faith traditions. I mentioned research on the benefits to families and youth that come from daily, weekly, and seasonal family rituals that give family members a strong sense of identity and a deep sense of security, especially in changing and challenging times for a family.

I spoke about my love of the Passover celebration and how I enjoyed the times I had been invited to celebrate Passover with my Jewish friends. I strongly encouraged the students to make regular Jewish ritual a meaningful part of their marriage and family life, and I promised that they and their future children would be grateful for their efforts to live Judaism to the fullest.

After the talk, Rabbi Perlmutter said he was both surprised and pleased that a Christian social scientist made such a persuasive case for the value of Jewish observance. He mentioned that he often said similar things to his Jewish students, but since he was a rabbi, they expected him to say those things. He said he was glad to have a non-Jewish social scientist say similar things that might even be more persuasive to his students. I was happy to assist a rabbi in his efforts to teach the power of Jewish tradition in strengthening families.

Fourth, while on sabbatical for a few months, I had the great pleasure of studying Torah and Talmud twice a week with Rabbi Chaim Adelman of the Chabad House at UMass Amherst. Rabbi Adelman is an Emissary of the Lubavitch Rebbe Menachem Schneerson (now deceased). Like hundreds of other Chabad rabbis across the globe, Rabbi Adelman was called to teach Jewish belief and encourage greater observance to Jewish law and tradition, but only to those already in the Jewish faith (there is no attempt to proselyte non-Jews). I enjoyed the fascinating hours spent studying with Rabbi Adelman. Chabad Judaism teaches the Kabbalah—the Jewish mystical texts such as the Zohar. I loved the combination of profound depth and prosaic practicality found in Chabad teachings. I also enjoyed several wonderful Jewish holidays with the Chabad community in Amherst.

Fifth, on the evening of the Jewish holy day Shavuot, which celebrates the reception of the Torah at Sinai, many observant Jews stay up the entire night studying Torah. This is done to make up for the fact that the Israelites at Sinai “slept in” on the day G-d1 revealed the Torah. I spent the entire evening studying Torah with a Reform congregation.

Sixth, when the Reformed congregation finished up at about 1:00 a.m., I went to the Chabad House where I stayed till 4:30 a.m. continuing to study Torah with Rabbi Adelman and other Hasidic Jews. That night, I was impressed by the deep commitment to study and to celebrate Torah, which was manifested by members in both congregations. Then on the day of Shavuot, I attended services at the Chabad House.

Seventh, I invited Rabbi Avrami Zippel of Chabad of Utah to lecture to a class I teach at BYU called Family in World Religions. In the class we study the way marriage and family life are addressed in various world faiths including Judaism. Rabbi Zippel generously shared2 a Hasidic perspective on several Jewish teachings and practices with my students.

Bar and Bat Mitzvahs, Torah and Talmud, and Holy Days

One of my favorite sacred gatherings to attend are Jewish bar and bat mitzvah celebrations.

The first time I attended one of these joyful gatherings, I was at the festive meal following the service (the seudat mitzvah). I was enjoying some chocolates when a woman came up and kindly introduced herself. As we chatted, I raved about the chocolates, and she said, “Oh, yes, those are Mrs. Greenblatt’s famous homemade rum toffees.” I asked, “Are they made with actual rum?” She responded, “Of course, that’s why they’re so good!” I said, “Whoops, I’m Latter-day Saint, and I don’t drink alcohol.” She smiled and said, “Ah, then nothing at this table is kosher for you. Let me bring you to the table with non-alcoholic chocolates.” One of the many things I appreciate about my observant Jewish friends is their shared understanding of religiously based dietary observances.

My four daughters and I celebrated Passover (Pesach) at the Chabad House—five of the most interesting and enjoyable hours of my life. For this wonderful home- and family-centered night we ate matzah flown in from Israel, and my daughters and I drank non-alcoholic wine as our Jewish friends became increasingly “joyful” drinking the four overflowing cups of real wine. Near the end of the evening, the rabbi, in fulfillment of a Chabad tradition, opened up the front door to “preach repentance to the Gentiles” (in a friendly Jewish way) to a large group of UMass Amherst students in the parking lot across the street.

On another occasion, I also celebrated Purim at the Chabad House. This fun—I might even say raucous—celebration involves everyone dressing up, often in outlandish costumes, drinking a lot of alcohol (of which I did not partake); one Talmudic teaching says you should get drunk enough that you cannot tell the difference between Haman (the bad guy) and Mordechai (the good guy). Each time the name of Haman is mentioned, everyone makes a wild ruckus to “wipe out his name” from memory.

An image emblazoned in my mind is the Rabbi Adelman standing before his congregation reading the Esther Scroll while dressed in drag with an ample bosom, a neon clown wig, and a red plastic clown nose. Rabbi Adelman typified the wonderful Jewish ability to combine profound scholarship and deep devotion with great warmth, humor, and friendliness.

Priestly Blessing

On one occasion, I was fortunate enough to be present with my Jewish friends when the Priestly Blessing was performed. It was one of the most sacred experiences I have enjoyed in which the name of God was invoked.

In Orthodox synagogues on certain special occasions, the Kohanim perform the sacred rite of the Priestly Blessing. The men who are direct descendants of Aaron (the brother of Moses and first hereditary priest of Israel) through the male line perform this rite in a solemn and sacred manner. They remove their shoes, cover their heads and arms in their prayer shawls (tallitot), and stand before the congregation.

While holding their hands outstretched toward the congregation, they chant the blessing3 given by G-d in Numbers 6:23: “The Lord bless you and keep you; the Lord make his face to shine upon you and be gracious to you; the Lord lift up his countenance upon you and give you peace.” The Cantor chants the blessing, and the Priests recite the blessing word by word so that it is done correctly. During the blessing, the Priests hold their hands in a special way so that their fingers form the Hebrew letter Shin (S), which stands for Shaddai (Lord Almighty).

The way the priests hold their hands was brought into public awareness when Leonard Nimoy, the actor who played Mr. Spock in the original Star Trek TV series, made this posture famous with his “Vulcan Salute.” As a boy, Nimoy had observed the Priestly Blessing when he attended services with his orthodox grandfather.

Because of the awe, holiness, and sense of G-d’s presence during the blessing, men cover their heads and faces with their prayer shawls and gather their children (even adult children) under their prayer shawls.

About the Priestly Blessing, G-d said in Numbers 6:27: “So shall they put my name upon the people of Israel, and I will bless them.” That day, during that Shavuot blessing, I learned that God continues to honor this promise that He made anciently.

When the Priestly Blessing was performed, I felt the power and peace of God coursing through me. There was a clear and unmistakable sense of sacredness. I felt that God—a true and living God—this was in fact blessing us. This experience is what our Jewish friends refer to as the Shekinah (the settling or dwelling of the divine presence of God), and what our faith calls the Holy Spirit.

Indeed, I felt the same way I had felt on those rare occasions when I had received an “Apostolic Blessing” given by an Apostle of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The Jewish Mikvah and Latter-day Saint Baptism

The interfaith journey I have shared so far began with a Jewish godmother at an Episcopalian baptism, and it now ends with Jewish mikvah symbolism at a Latter-day Saint baptism.

The photo shows us gathered in front of the baptismal font just before my daughter Rachel’s eight-year-old daughter Eliza was baptized by her father, Collin, on her eighth birthday. (L-R David, Collin, Eliza, Rachel, Mary).

In Jewish practice, the body of water in which men and women are immersed is called a mikvah. Mikvah means “collected waters” and a mikvah must be connected to “living waters” (e.g., ocean, natural spring, rivers, lakes, rainwater) so that it symbolizes the primal creative waters from God and not touched by human hands.

The mikvah is a profoundly meaningful and spiritually rejuvenating practice for women. Many observant Jewish women attend a mikvah before they are married. In Orthodox Judaism married women must attend mikvah each month after menstruation before renewing sexual relations with their husbands. The Mikvah Lady supervises the process and supports the women who come to the mikvah.

For Eliza’s baptism, Rachel was the main “mikvah lady” in that she helped Eliza prepare practically and spiritually for her baptism in various ways. Eliza’s two grandmothers, my wife Mary (Rachel’s mom), and Collin’s mom Jeralyn served as the two witnesses required at an LDS baptism to assure the prayer is said correctly and the person is fully immersed. Given that Mary and Jeralyn will watch over and support Eliza’s spiritual growth, you could say they are her god grandmothers.

If the baptismal prayer is not said correctly or a part of the person (e.g., hair, feet) is not completely covered by water, the prayer and immersion are repeated. In this case, the prayer and immersion were performed three times (often Jewish women immerse three times).

Those of us who were present at Eliza’s baptism felt connected across generations of faith and family life. We also felt the spiritual presence of the Lord, what our Jewish friends call the Shekinah. While my Jewish godmother was not physically present at Eliza’s baptism, I like to think that Ann also was there in spirit.

Ann Scinski chose to participate in a Christian baptism out of love and devotion to her Christian friend, my mother. My mother chose friendship over faith in that she would have forgone my baptism if Father Ewald had not allowed a Jewish woman to be my godmother.

My mom chose to have me baptized into her faith when I was not able to make a choice about that. This is consistent with the practice with all faiths that practice infant baptism, with Judaism that practices infant circumcision for boys and naming for girls, and, to some extent, even with my faith that practices naming and blessing of infants, so they are placed on the records of the Church. Indeed all major faiths except Buddhism, have some kind of religious ritual for infants.

In a full-circle action, about one year after my mother died of cancer, I returned the favor and baptized Mom into my faith. I did so at the Provo Utah Temple when I baptized my wife, Mary, vicariously “for and in behalf of” my mom, Elizabeth. So, I immersed my wife acting in the stead of my mother to provide the opportunity for her to make a choice in the next life.

I will not, however, be doing the same for my Jewish godmother. One of the things I am most gratified about my faith is that it does genealogy and builds temples in order to provide every human being who ever lived an opportunity to choose whether or not to accept that offering.

However, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints specifically prohibits its members from doing vicarious baptisms for Jewish persons unless that person is a direct ancestor of the member. Judaism is the only faith for which the Church makes this exception. Thus, although she was never really observant and married a Christian man and participated in my Christian baptism, I will honor her life by not having someone baptized for and in behalf of my dear Jewish godmother, Ann Scinski.

Gratitude for the Gift of Sacred Gatherings

Members of our family have been welcomed to sacred gatherings in many places and among many peoples, especially Jewish places and people. All of us are grateful to our many Jewish friends who have welcomed us with warmth and kindness. We have learned much from our Jewish friends about how to worship God, how to celebrate life, how to make the Sabbath Day holy, how to celebrate sacred occasions, and how to make our homes places of sacred family gatherings.

Our Jewish friends have given us gifts we cannot repay: the great blessings that flow from joining in regular sacred gatherings with friends and loved ones to honor God and the eternal truths that flow from God.

To all our Jewish friends, in whatever conditions and challenges you face, May the Lord bless you, and keep you; may the Lord shine His face upon you, and be gracious to you, and may He give you peace.

1. Orthodox Jewish writings usually omit the middle letter in the divine name and write “G-d” to show respect to the Lord (who they also often call Hashem which means “The Name”).↩

2. If you are interested in what Rabbi Zippel said to my students, you can watch the lecture here.↩

3. Parents also speak this blessing over their children on Friday evenings [Shabbat], and many Rabbis and Christian ministers do so during various religious services.↩

For additional reading:

Evangelical Christian Families: “God Wants Us … To Be Strong”

Latter-day Saint Families: Eternal Perspectives

Jewish Families: How Teachings and Traditions Strengthen Marriage and Family Life

Strengths in Diverse American Families of Faith

The post Sacred Experiences with Jewish Friends appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →