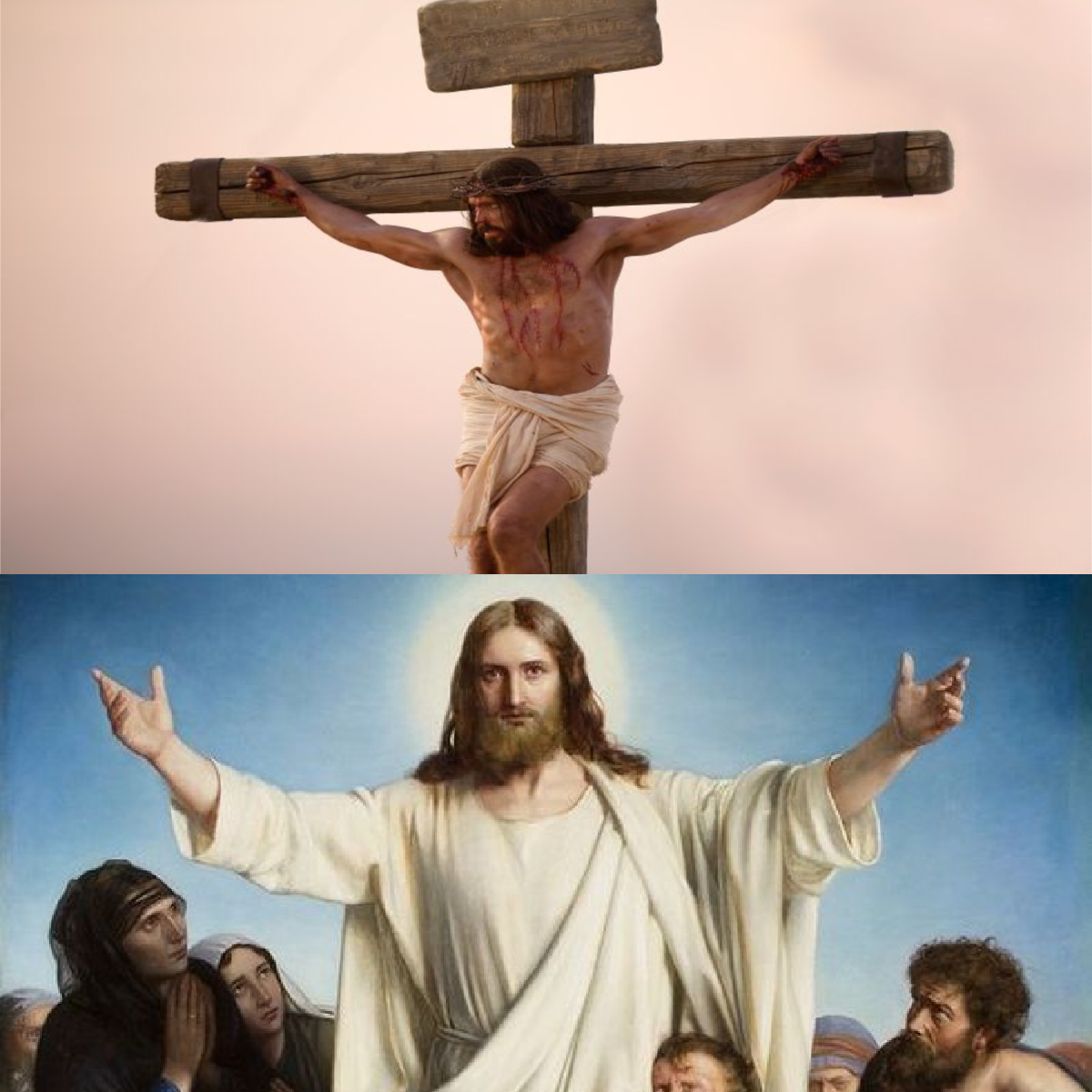

A long-held question that I have considered is “why was Christ crucified?” More than just “why did He need to suffer and die to fulfill His mission?” I’ve wanted to understand why his death was by crucifixion, and whether there was a larger message in the method of crucifixion itself.

The sheer pain of this manner of death is significant. Crucifixion was once said by President J. Reuben Clark Jr. “to have been the most painful [death] that the ancients could devise.” As Tad Callister elaborated:

It held the victim for hours at the brink of life, never quite releasing him, yet all the while inflicting upon the nerves and senses all he could painfully and consciously endure. It took [a] man to his threshold of pain, but not beyond. Throbbing, pulsating pain was felt by a victim who would welcome death, but could find no such early relief.

On a social level, the Pharisees also considered crucifixion such a low death that it disqualified its victim from ever being resurrected—with a person suffering such a fate considered accursed and often left to decompose on their cross (giving even more poignant meaning to the fact that Jesus’s friends begged to take His body for a decent burial). And in his book, “The Day the Revolution Began: Reconsidering the Meaning of Jesus’s Crucifixion,” Christian scholar N.T. Wright also points to social and political meanings of the crucifixion that “would have been deeply intuited and understood” by all involved —namely, a message from the Romans that: “We are superior, and you are vastly inferior” and “We’re in charge here, and you and your nation count for nothing.” On this basis, Wright explains that only crucifixion—being killed in the one way that was meant to show Rome controls utterly everything and can do whatever it wants to you—would allow the resurrection to mean what it did, demonstrating that Rome (and all earthly powers) really had no power.

B.J. Spurlock also highlights potential significance in the crossing horizontal and vertical lines of the cross itself, as a “symbol the Lord chose because it invokes his intentions to bring to earth that which is in heaven and then have it spread on all directions horizontally” (referencing a similar analysis of the Latin word “templum”).

All this is valuable. Yet is there more to understand? The words of the resurrected Christ found in the Book of Mormon point to even deeper answers for me, beginning where He states, “I have given unto you my gospel, and this is the gospel that I have given unto you—that I came into the world to do the will of my Father, because my father sent me. And my Father sent me that I might be lifted up upon the cross” (emphasis my own here and below).

Notice Jesus’s word choice, highlighting how central the crucifixion was to His mission —why His Father sent Him—to be “lifted up” upon the cross. While believers attest to the larger atoning reason for this death, why does the Lord Himself give much emphasis to the cross in explaining His gospel? What he said next opened my mind and eyes to some surprisingly beautiful illustrations found just beneath the darkness of His tortured suffering.

Jesus continues: “… and after that I had been lifted up upon the cross, that I might draw all men unto me, that as I have been lifted up by men even so should men be lifted up by the Father, to stand before me, to be judged of their works whether they be good or whether they be evil.”

He then says in summary, “… and for this cause have I been lifted up,” in other words, “this is why I was crucified.”

This is where I saw what I had not seen before: a beautiful message conveyed in a stunning inversion, hidden by the ugliness and barbaric nature of his suffering—a symbolic lesson that says something profound about everything that transpired. Being raised unto death after man’s judgment would provide the juxtaposed inversion of what would follow—perfect judgment and the supernal gift of being raised unto eternal life.

I don’t believe this powerful lesson could have been found in another method of death typically used in that era.

Deeper meaning in all things. There are symbolic messages, of course, in many elements of Jesus’ life. For instance, in the final miracle before His atonement, Jesus lifts Lazarus from the dead. This would be a fitting capstone to His many personal miracles, and it would also foreshadow His own death and resurrection; a hope-affirming, life-restoring miracle performed for all whoever had and ever would live.

In the days that follow Lazarus being lifted up, we find other profound symbolism. His triumphal Passover entry into Jerusalem is filled with deep meaning. The gate was believed by the Jews to be the place the Savior would enter the holy city and the returning Messiah would likewise be presented. The garments or cloaks placed upon the ground were not simply garments—but tallits, or prayer shawls worn by the Jews that were framed by commandments and the words King of Kings and Lord of Lords. Palm fronds were also used in times of celebration and victory and hearken back to David’s royalty.

The Last Supper likewise has deep metaphorical meaning. What then of the agonizing suffering that would follow? While the nature of Christ’s atoning weeks is incomprehensible on some level to mortal minds, there are important lessons God would have His children understand.

To be clear, Satan, who has always sought to disrupt the mind, will, and plan of God, surely influenced those who sought to bring suffering, betrayal, and improper judgment upon Jesus. Yet despite this, Father considered and accounted for the impact of this very malevolence much as He did in the garden with our first parents. In great irony, Satan would thus become an important key to unlocking the plan that he had worked so hard to disrupt from the very beginning.

A sacred contrast. Here are the contrasts that I believe offer an important message about not only that passion week—but about everything else that follows it, for all of us. Compare the following lists:

What was done to Him

Scarlet robe

Crown of thorns

Imperfect Judgment

Arms forcibly outstretched

King of the Jews placard to mock

Lifted unto death

What He does for us

Clothed with robes of power

Crowned with glory

Perfect Judgment

Arms Freely Outstretched

Prophesied messiah and king

Lifted unto everlasting life

In contrast to this lifting up on the cross, Jesus, in the words of Paul, would soon after be “raised up from the dead by the glory of the  Father,” or “raised up the third day, and showed him openly” in the words of Luke, who also contrasted this subsequent lifting with his death, “The God of our fathers raised up Jesus, whom ye slew and hanged on a tree.” All this was prophesied by Jesus as well, who told his apostles earlier in his ministry that after “The Son of man must suffer many things … and be slain” He would be “raised the third day.” Those who betrayed, captured, tortured, mocked, or killed the Savior would not have known the immense significance to be found in any of their actions.

Father,” or “raised up the third day, and showed him openly” in the words of Luke, who also contrasted this subsequent lifting with his death, “The God of our fathers raised up Jesus, whom ye slew and hanged on a tree.” All this was prophesied by Jesus as well, who told his apostles earlier in his ministry that after “The Son of man must suffer many things … and be slain” He would be “raised the third day.” Those who betrayed, captured, tortured, mocked, or killed the Savior would not have known the immense significance to be found in any of their actions.

Earlier echoes of the same metaphor. If we look even deeper, we can find this visual association predating Jesus. John recounts: “And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so, must the Son of man be lifted up: That whosoever believeth in him should not perish but have everlasting life.”

In the Book of Helaman, we read Nephi’s entreaty to his agitated people:

Yea, did he not bear record that the Son of God should come? And as he lifted up the brazen serpent in the wilderness, even so shall he be lifted who should come. And as many as should look upon that serpent should live, even so as many as should look upon the Son of God with faith, having a contrite spirit, might live, even unto that life which is eternal.

In both instances, the Lord transformed a symbol of death into a symbol of life by renewing its purpose. For the Savior to be raised up and to raise or lift us up in our own resultant “newness of life,” He first had to descend “below all things in order to rise above all things,” in the words of President Russell M. Nelson.

Of course, the use of symbolism is found in nearly all scripture and is common throughout all forms of worship and learning. As Latter-day Saints, we are accustomed to rich symbols in our church and temple worship—with ordinances that involve gestures or illustrations to help us understand who we worship and the rich purposes behind what we do or covenant to do. For instance, when we partake of the sacrament we remember what and who the emblems represent. We observe an altar with linens that are analogous to the tomb and burial cloth of the Savior. In baptism, we also appreciate the rich symbol of the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus—recognizing our own death of sorts, putting off our former natural self, and becoming a saint through His atonement. After we are thus reborn, we receive His name, His inherited likeness, and the metaphoric journey continues in the temple.

As appreciated as so many of these symbols are to Latter-day Saints—and indeed, to many other Christian believers around the world—I still find it remarkable how much I have yet to learn in my study of the Savior. Elder Ulisses Soares’ friend said it right, “… there is always something wonderful and fascinating to learn about Jesus Christ and His gospel.”

Blessed by the deeper symbolic significance of the Passion itself. This basic series of events leading up to the crucifixion of Jesus is familiar to most Christians. The New Testament details that the Roman centurions placed a purple or scarlet robe upon Jesus, followed by a crown of thorns. This was done to openly mock Him, exactly at the moment of His undeserved humiliation and disadvantage. Yet, despite the mocking of His kingship with their sense of Roman superiority, Christ was, in reality, the one true King.

Before them was the King of the Jews who had willingly come, with outstretched arms, to bless, redeem and finally gather them. His true desire was to clothe them in His power and crown them with His glory. Yet even though He appeared with open arms, instead of recognizing and accepting His gesture and supernal gifts, centurions would nail and fix these same open arms to a tree—but not before he was paraded in front of His people to be mocked again.

In all this, the “King of heaven” and “King of kings” willingly submitted to the servants of the king of the great Roman army. After His garden betrayal, Jesus would remind Peter that He had the authority to call upon legions of Heaven, but would not.

Soon after Jesus enters Jerusalem triumphantly, He is forced to lament, “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, thou that killest the prophets, and stonest them which are sent unto thee, how often would I have gathered thy children together, even as a hen gathereth her chickens under her wings, and ye would not!”

Those who for so long had foretold of their coming Messiah could not recognize that same Messiah standing before them in the flesh. They knew not who He was and therefore, to a lesser degree, knew not what they did. He had been betrayed by His own, once again. Then, in the imperfect and nearsighted court of public opinion, His fate was sealed. He was condemned by man’s judgment and sentenced to be lifted up.

Here, in the most dramatic and ironic fashion, His perfectly outstretched hands were, for a moment, compelled to remain extended, long enough for Him to complete His mission. In being so lifted up, He descended below the brutality of the one person who had opposed Him from the beginning and who was the author of His staggering suffering.

enough for Him to complete His mission. In being so lifted up, He descended below the brutality of the one person who had opposed Him from the beginning and who was the author of His staggering suffering.

We can be thankful this spring, and always, that the story doesn’t end there, as Jesus is the author and fortunately also the finisher of our faith. As the true Light and Life of the world, His specialty and His authority are taking dark stories and revealing the light in them. As the words of Isaiah reflect, despite the wickedness of man, “His hand is stretched out still” (a phrase which the Book of Mormon makes clear refers to an arm of mercy and not just punishment).

As the Lord taught Adam anciently, according to Latter-day Saint scripture, “all things bear record of me.” Strikingly, that even includes his method of torture and death.

Referring to this same earth-changing week of his death and resurrection, Rob Gardner says in his work The Lamb of God, “Hope did not die here, but hope was given. Here is hope.”

Elder Jeffery R. Holland, an apostle in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints elaborated:

This Easter I thank Him and the Father, who gave Him to us, that Jesus still stands triumphant over death, although He stands on wounded feet. This Easter I thank Him and the Father, who gave Him to us, that He still extends unending grace, although He extends it with pierced palms and scarred wrists. This Easter I thank Him and the Father, who gave Him to us, that we can sing before a sweat-stained garden, a nail-driven cross, and a gloriously empty tomb.

Then he quoted these lyrics of the sacramental hymn, “How Great the Wisdom and the Love.”

How great, how glorious, how complete

Redemption’s grand design,

Where justice, love, and mercy meet

In harmony divine!

Prophesying before the Chosen one’s mortal ministry, Malachi attested, “the Sun of righteousness [shall] arise with healing in His wings; and ye shall grow up as calves of the stall.”

I bear my own joyful witness that He who is the perfect Sun and the Son shall rise with healing in His wings to judge us perfectly and lift us up. And why? Because this was His cause.

The post For This Cause Have I Been Lifted Up appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →