In our Introduction to this series, we made the case that Latter-day Saint psychologists should take up Elder Neal Maxwell’s invitation to build bridges between the Restored Gospel and the secular discipline while keeping our citizenship in the kingdom and maintain our loyalty to core truths of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. We suggested what we believe are thirteen non-negotiables, or perhaps thirteen foundations, of a genuinely Latter-day Saint perspective. In the rest of this series, we will endeavor to expound upon each. The first foundation is thus:

Revelation from God is a vital source of wisdom and knowledge.

Revelation from God is a lynchpin of the restored gospel of Christ. The Ninth Article of Faith in the Church of Jesus Christ reads, “We believe all that God has revealed, all that He does now reveal, and we believe that He will yet reveal many great and important things pertaining to the Kingdom of God.” Furthermore, Latter-day Saints believe that ordained servants of God— prophets and apostles, and other assigned leaders—have a divine stewardship to receive spiritual guidance and warn us of spiritual dangers. These ordained leaders have ecclesiastical authority to set forth a vision of the good life and human flourishing, and the sorts of things that we should do to pursue it.

If disciples-scholars seek to be faithful to their covenant to stand as witnesses of Christ and His restored gospel in all they do (Mosiah 18:9), they must be willing to pursue their research in a way that does not foreclose turning to revealed truth for insight. As S.D. Gaede put it: “Christians should allow their Christianity to permeate their entire lives, and not just pre-selected portions of it.” If we quarantine our scholarship from our faith—for fear of our faith “contaminating” our scholarship—we are missing out on a tremendous wealth of possibilities.

At the same time, we should also not engage in sloppy scholarship whose sole intention is to score quick or easy theological points. Many instinctively take the “two hats” approach to faith and scholarship—where they embrace theistic assumptions at church and at home, but secular assumptions when doing research and scholarship—perhaps because they have too frequently seen faith and scholarship blended in problematic ways. Our worldviews inevitably create, shape, inform, and otherwise provide substance and texture to what we observe.

Assumptions to challenge—Scientism. A Latter-day Saint perspective in psychology will challenge the assumptions and excesses of scientism. We should note that science and scientism are not the same thing. Scientists the world over do rigorous science without embracing scientism. In contrast, scientism elevates the norms and presumptions of scientific exploration to the realm of an ideology. It presumes that the methods and approaches that were fruitful in the natural sciences can be employed with similar success when studying human experience. C. Stephen Evans has described scientism as “the belief that all truth is scientific truth and that the sciences give us our best shot for ‘knowing things as they really are,’” including human behavior and the social world.

Brian J. Walsh and J. Richard Middleton explain, “Foundational to the modern world view is the deeply religious belief that human reason, especially in the form of the scientific method, can provide exhaustive knowledge of the world of nature and of mankind.” It is that last part especially—and of mankind—that moves the project from mere science to scientism. An example of scientism can be found in the work of neuroscientist Sam Harris, who wrote, “The moment we admit that questions of right and wrong, and good and evil, are actually questions about human and animal well-being, we see that science can, in principle, answer such questions.”

While Harris’s approach is extreme, others have made more modest claims that nonetheless illustrate scientism at work. For example, the famous philosopher A. J. Ayer, a staunch advocate of scientism, asserted that “there is no field of experience which cannot, in principle, be brought under some form of scientific law, and no type of speculative knowledge about the world which it is, in principle, beyond the power of science to give.” For our purposes here, we can think of scientism in three distinct (but overlapping and complementary) ways:

1. A worldview that treats scientific methods as the only (or most) important source of truth. For example, many assert that—when it comes to understanding human experience and behavior—we should rely solely upon the methods familiar to the natural sciences. From this view, any reference to divine revelation, religious texts, or moral tradition is treated as categorically out-of-bounds for psychological researchers. This is because the scientific method is seen as reliable in precisely the ways that religious beliefs and experiences are not. Scientism hands us a story in which the religious superstitions of yesteryear are rooted out in favor of evidence-based theories and practices of today.

2. The assumption that the scientific method allows social science research to achieve objective, value-neutral results. Many further assume that, unlike philosophy or religion, the scientific method allows people to arrive at conclusions that are not filtered through or influenced by ideological, political, or moral worldviews. “It is often pointed out,” S. D. Gaede explains, “that although scientists come from a wide variety of backgrounds, holding different values, beliefs, and attitudes, they nevertheless reach remarkably similar conclusions when they enter their scientific laboratories.” In short, the methods and conclusions of the social sciences are often assumed to be value-free, occupying a privileged space where the superstitions and biases of religion, tradition, and culture can be bracketed and set aside in favor of systematic analysis of raw, empirical evidence. Alister McGrath put it this way:

One of the most influential myths of the modern period has been the belief that it is possible to locate and occupy a non-ideological vantage point, from which reality may be surveyed and interpreted. The social sciences have been among the chief and most strident claimants to such space, arguing that they offer a neutral and objective reading of reality.

3. A worldview that treats scientific and technological advancement as the primary way to address human suffering. Many assume that social scientists can and should become the pre-eminent voice of authority when it comes to improving the human condition. As Steve Wilkins and Mark Sanford put it, “[T]he therapist has replaced the pastor or priest as the professional person to look to for relational or behavioral assistance.” Psychologists are increasingly seen not only as the primary experts on how we can address human suffering but as engineers of human happiness and well-being. As Walsh and Middleton explain:

Science becomes the source of revelation. Instead of the priest of the medieval period, the scientist clad in authoritative white dispenses “knowledge unto salvation.” The original sin is no longer disobedience to God; it is ignorance, irrationality, or misinformation.

Our deference to the social sciences for answering questions about the good life and human flourishing becomes scientism when we do so to the exclusion of divine and revelatory sources.

All three of these assumptions—(1) that scientific methods should be privileged as the primary source of truth in the social world, (2) that properly-conducted scientific investigations are unbiased and value-free, and (3) that through the application of these methods, the social sciences will unlock the keys to human flourishing—are simultaneously features and examples of scientism. We argue that none of these assumptions are essential to engaging in a rigorous, scholarly (and even scientific) study of human experience and behavior.

One example of scientism is the presumption that if a researcher draws on religious conviction for insight while conducting scholarly research, he undermines his credibility as a researcher. Scientism can prime us to see religious conviction as a “contamination” of our scholarship in a way that introduces bias into the research process. Some even cite a long-standing narrative that religion has historically been an anchor that has curtailed scientific progress, and that the history of science is one in which the triumphs of scientists help overcome the superstitions of religion. The narrative is greatly exaggerated—scientists throughout history have made valuable scientific discoveries that were facilitated by deeply held religious convictions.

Social science research is a value-laden process.

Those who embrace scientism presume that there is a privileged philosophical worldview that does not introduce bias. They assume that the scientific method allows researchers to pursue value-neutral results. This is what BYU researchers Brent D. Slife, Jeffrey S. Reber, and G. Tyler Lefevor have termed “the myth of neutrality.” Many researchers, they note, tend to “think of this [scientific] neutrality as if their methods are transparent and unbiased windows to the real objective world.” Unfortunately, as they also note, this represents “naïve views of science and the scientific method, views that must ignore a large philosophy of science literature to maintain their naivete.”

Contrary to the claims of scientism, by rejecting religious influences on our worldviews, we are not occupying a privileged, value-free territory. Rather, we are simply supplanting theistic assumptions with naturalistic assumptions (or expressive individualism, and so on). None of these presumptions can be verified by empirical evidence since they are philosophical frameworks that are pre-empirical. As Slife, Reber, and Lefevor further point out, our research methods are “not revealers of an uninterpreted or assumption-less world; all methods, and thus all findings, are informed and shaped by assumptions that interpret the world.”

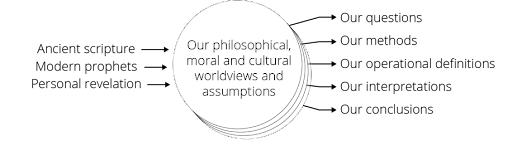

The term pre-empirical assumptions refers to philosophical perspectives and value systems that precede scientific investigation and which cannot themselves be empirically verified. However, these assumptions inform the questions we ask, the methods we use, and how we interpret our findings. They include worldviews like naturalism (the assumption that only the natural world exists or can be known), determinism (the assumption that there is no such thing as freedom because everything that happens is caused), and expressive individualism (the assumption that self-expression is a paramount human virtue). Daniel Dennett observed:

Scientists sometimes deceive themselves into thinking that philosophical ideas are only, at best, decorations or parasitic commentaries on the hard objective triumphs of science, and that they themselves are immune to the confusions that philosophers devote their lives to dissolving. But there is no such thing as philosophy-free science; there is only science whose philosophical baggage is taken on without examination.

Brigham Young University (BYU) professors Brent D. Slife and Richard N. Williams explained, “All theories in the behavioral sciences make assumptions about people, and those assumptions are most often not explicit.” Walsh and Middleton put it this way: “All theoretical analysis, whether in the natural sciences, humanities or social sciences, occurs within the context of a philosophical framework or paradigm.” Many other thinkers have made similar arguments. In this regard, Paul Moes and Donald Tellinghuisen claim;

Most psychologists rarely raise deep questions about human nature in their research or practice, but typically have unspoken assumptions about our ‘essence’ and how this influences the way we act. In fact, psychologist Noel Smith suggested that ‘psychology may be the sorriest of all disciplines from the point of view of hidden biases,’ because psychologists rarely state or even acknowledge their presuppositions.

In short, research in the social sciences is not value-free or value-neutral. It is saturated with these sorts of pre-empirical worldviews and assumptions. For just one example, determinism is a philosophical assumption that assumes that all human behavior can be explained in terms of cause and effect—and this assumption informs the questions we ask, how we define the variables of our study, the methods we use to find the answers, and the conclusions we draw from the data. However, determinism is (and always will be) a philosophical assumption that cannot itself be verified empirically. (More on this, and many other examples, in future chapters.) “Like the naturalist, the Christian has the legitimate right to approach science from the vantage point of a specific world-and-life view.”

If social science research is shot through and through with pre-empirical moral and philosophical presumptions, we can see why Neil Postman stated that the “social sciences are merely subdivisions of moral theology.” Postman’s rhetoric might seem like hyperbole, but his point was simple: social scientists are first and foremost storytellers, weaving compelling narratives about human experience that are often replete with moral and religious consequence. In fact, as sociologist Jason Blakely has compellingly shown, “social science rarely simply neutrally describes the world, but rather plays a role in constructing and shaping it.”

Even though social scientists make use of many methods that are employed in the natural sciences, the social sciences have not achieved the same sort of consensus we often find in the natural sciences. Rather than a monolithic discipline, psychology is full of different franchises (behaviorism, psychodynamics, humanistic psychology, neuropsych-ology, and cognitive psychology, to name a few). These franchises all make fundamentally different assumptions about the kind of universe we live in (metaphysics), how to best study the universe (epistemology), who we are as people (anthropology), and what constitutes the flourishing life (ethics). And within each franchise are many competing perspectives and voices, with diverging views on each of the above questions.

Each of these competing franchises tells fundamentally different stories about human experience. Behaviorists describe human experience in terms of environmental stimulus and response. Cognitivists describe human experience in terms of innate categories and processes of the mind. Humanistic psychologists describe human experience in terms of aspirations, goals, needs, and identity. Neuropsychologists describe human experience in terms of brain chemistry and neuroanatomy. All of these perspectives complement their stories with empirical analyses. All of these perspectives make diverging assumptions about the sorts of questions that are interesting, the best approaches for rigorously studying human experience (quantitative vs. qualitative, for example), and the sorts of answers that are admissible.

Certainly, in this buzzing, vibrant disciplinary discourse there is room for storytelling that centers on (or at the very least includes) agency, moral accountability, compassion, and divine engagement with mankind. To argue that a wide array of pre-empirical worldviews are permissible in the discipline—ranging from behaviorist to humanistic, from cognitivist to neuroscientific—while singling out theistic perspectives as uniquely and categorically impermissible, is to nurture a secular disciplinary dogma and ideology that has no foundation in empirical evidence.

We can evaluate pre-empirical assumptions in light of revealed truth.

Our philosophical, moral, and cultural worldviews can be compared to flashlights of varying color that illuminate our investigations, or lenses through which we view the world. Lighting a room with a colored flashlight—or wearing a colored lens—reveals the room in a way that is inflected by the color of the light (or the lens). In the same way, our worldviews inevitably create, shape, inform, and otherwise provide substance and texture to what we observe. This is inescapable and universal. As Moes and Tellinghuisen explain, “Worldviews inform morality by shaping what will be studied, how people will interpret the findings, and even how they will implement the findings.”

Given that all research endeavors are embarked from the perspective of pre-empirical worldviews and philosophical assumptions, it is perfectly legitimate to engage in scholarly pursuits using different assumptions as a starting point. Gaede explains it this way:

[A Christian perspective in the social sciences] is proper because assumptions about the ultimate nature of reality are unavoidable. They must be made, and are made, in the social sciences just as elsewhere. Like the naturalist, the Christian has the legitimate right to approach science from the vantage point of a specific world-and-life view.

President Dallin H. Oaks, speaking to Church Education System instructors and leaders, taught that a religion that claims to be grounded in revealed truth may very well find itself at significant odds with the prevailing teachings of the world—and not just in terms of its conclusions, but also in terms of its premises. Elder Oaks noted that “on many important subjects involving religion, Latter-day Saints think differently than many others.” He continued:

When I say that Latter-day Saints “think differently,” I do not suggest that we have a different way of reasoning in the sense of how we think. I am referring to the fact that on many important subjects our assumptions—our starting points or major premises—are different from many of our friends and associates.

It is because of this tendency to “think differently” that we believe Latter-day Saints need to learn how to think more critically about the precepts that are taught and accepted in modern psychology. Thinking critically, in this context, does not merely mean thinking skeptically or even rigorously (though rigorous thinking is important). Rather, it means identifying basic philosophical assumptions, and carefully comparing and contrasting those assumptions with their alternatives. It means taking those assumptions seriously by exploring their logical and practical implications. An Evangelical colleague of ours, David N. Entwistle, persuasively argues:

Because all observation is affected by ideology, integration [of scholarship and divine truth] must begin with the construction of a Christian worldview … As a corollary, this necessitates that Christians not merely compare the results of psychology and theology, but that they also explore the underlying influence of assumptions and worldviews on our reasoning and conclusions.

In a similar way, BYU professor Stephen Yanchar argues that, from a Latter-day Saint perspective, “the revealed truth can provide a comparative basis for evaluating the veracity and utility of various assumptions and values that inform research and theorizing in the scholarly disciplines.” Elder Merrill J. Bateman, a former president of BYU, once promised, “We will be more productive and enjoy more freedom if we examine and test secular assumptions under the lamp of gospel truth.” In short, Christianity can become the framework by which we evaluate our other worldview assumptions. We are reminded of C.S. Lewis’s pronouncement when he said, “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen: not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.”

We are not inviting Latter-day Saint social scientists to engage in sloppy or ideologically driven research, in order to shore up particular theological claims, moral worldviews, or religious beliefs. As disciple-scholars, we can engage in rigorous theorizing and empirical investigation even as we evaluate our philosophical presumptions in the light of revealed truth. In fact, our research and theorizing can be even more careful and rigorous because of our willingness to articulate and investigate our pre-empirical assumptions. Walsh and Middleton explain:

Indeed, the fact that many (if not most) scholars are actually unaware of their point of view is one of the main causes of academic superficiality. With this superficiality (“I just look at the facts”) comes the inability to be self-critical (“This is just the way things are”) because such scholars never explicitly consider their starting points.

In other words, we can reduce the superficialness of our research and theorizing by considering our philosophical starting points. When researchers uncritically default to secular or naturalistic worldviews, their research and theorizing are not inherently more rigorous simply because they resort to unexamined, disciplinary defaults. Another way to put it is that there is nothing unempirical about interrogating our pre-empirical worldviews, nor is there anything less rigorous about being more articulate about our foundational assumptions. “If we do not approach scholarship on the basis of Christian assumptions about the nature of reality, then we are getting our assumptions somewhere else.”

By contrast, when we can articulate the philosophical premises of a Latter-day Saint perspective in psychology, we can begin to see the social sciences anew. Our point here is not that we should blithely reject anything and everything we disagree with. Our point is simply that there is room enough in the discourse for more competitors in the marketplace of perspectives within psychology. We can and should carve out a corner in the discipline for stories about ourselves told from within a universe that assumes that we are moral agents, that we live and act in a morally-inflected world, and that human flourishing centers on repentance, forgiveness, compassion, and participating in covenant communities. Gaede continues further:

For the Christian … such a perspective is not only legitimate, it is also necessary. It is necessary, first, because integrity demands it. To call oneself Christian is to affirm that Jesus Christ is Lord. And from His Lordship no area of life can be safely excluded. It is necessary, second, because the social sciences are in need of Christian thinking. Without it, these disciplines will be less than they should be and the world will be deprived of a source of understanding it both needs and deserves.

We echo Elder Maxwell’s statement: “[Latter-day Saint] behavioral scientists must extract both the obvious and hidden wisdom embedded in the value system of the gospel of Jesus Christ.” He stated further that within prophetic teachings “are certain important clues concerning that human behavior which produces lasting growth and happiness and that which produces misery.” Even more powerfully, Elder Maxwell also taught, “the deep problems individuals have can only be solved by learning about ‘the deep things of God,’ by confronting the reality of ‘things as they really are and things as they really will be.’”

For example, ancient scripture and modern prophets might have nothing to say about what specific therapeutic intervention increases desired patient outcomes. But it can help inform whether determinism should be our primary framework for theorizing about human action, or the extent to which expressive individualism should be our primary paradigm for understanding human nature and flourishing. The Gospel of Jesus Christ may have little to offer on which functions of the brain are most closely connected with the amygdala, but it can help inform whether radical materialism should be the exclusive or primary lens for understanding human experience. (More on each of these philosophical perspectives in later chapters.)

And as we will explore throughout the rest of this book, the teachings of ancient scripture and modern prophets can serve as a foundation for a set of values that influences the sorts of questions we ask. Moes and Tellinghuisen explain, “Scientists’ interests and research agendas flow from what they value, and values arise from many sources, including … religious worldview.” We will suggest at various points throughout this book that our interests as Latter-day Saints—that is, the sorts of questions we find pressing and important—may at times be different from those of our secular counterparts. In these ways, revelatory sources can play a vital role in keeping our research and theorizing anchored in divine truth.

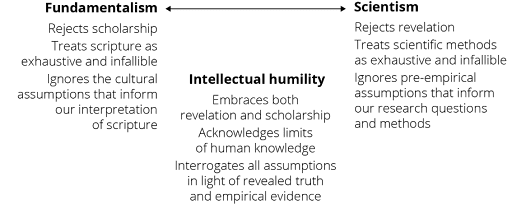

Pitfalls to avoid—Fundamentalism. While scientism forecloses revelation as an important approach to truth, fundamentalism forecloses on scholarship (and science) as an important approach to truth. We are invited not merely to be disciples, but to be disciple-scholars. This means we can and should take high-quality research seriously (even as we interrogate the assumptions of the research through the lens of the Restored Gospel). Indeed, as Elder Maxwell also taught, “For a disciple of Jesus Christ, academic scholarship is a form of worship … another dimension of consecration.”

A fundamentalist approach, however, might lead us to adopt a stridently adversarial approach to secular theories in psychology, in a way that alienates rather than builds bridges. Elder Maxwell argues that it is possible to build bridges between the social sciences and revealed truth “without compromising the concepts contained in the revelations of God and without being so eager that our scholarship becomes sloppy.” He further asserts that we should become bilingual, proficient in the language of research and scholarship as well as the language of faith.

With respect to the social sciences, fundamentalism is sometimes manifested as an un-nuanced, absolutist understanding of human experience. An example of this sort of thinking is related by Entwistle:

I once met a pastor who was amused to find that I taught psychology at a Christian college. His eyes twinkled as he said, “I’ve heard it said that psychology is just sinful human beings sinfully thinking about sinful human beings.” His comment seemed to imply the belief that he had just tumbled the house of cards on which my profession was built.

Similarly, some have come to believe—perhaps because they are sensitive to the dangers of scientism—that biology and physiology play no role in our emotional lives. They regard all forms of depression, anxiety, and other emotional disorders as spiritual matters to be resolved entirely through prayer, and righteous living. In so doing, however, they ignore very persuasive scholarship that demonstrates that our physiology can play a significant role in our emotional experiences. Denying important insights and understandings just because they happen to come from secular sources is an example of fundamentalism in action.

Another example might include those who believe that therapists and counselors should play no role in helping struggling individuals and that the problems that normally lead people to seek help from therapists should instead be addressed solely by ecclesiastical mentors and leaders. When we do this, we make the error of scientism in precisely the other direction: rather than assuming that scientific and technological advancement in the social sciences are the primary way to address human suffering (scientism), we assume they play no appropriate role whatsoever (fundamentalism).

Furthermore, a fundamentalist approach rejects the importance of good scholarship and might instinctively object to the findings of good researchers whenever those findings contradict their assumptions. Moes and Tellinghuisen ask, “What is a Christian to do if a research finding goes against her Christian beliefs?” They continue:

Christian research psychologist Scott VanderStoep writes that the first, gut response that you might have—to simply reject it, saying ‘I don’t believe it’—is unacceptable if we are to take any psychological research seriously. Research needs to be critiqued on its scientific merit. … First, this means that when Christians are evaluating research, we must do so respecting science’s rules. Assessing research quality begins with examining whether the research methodology in the study allows for the conclusions that were made by the experimenters.

In other words, we can and must take research seriously, and if and when we critique it, we should not do so solely on the grounds that the conclusions of the research contradict our religious dogmas or assumptions. “All people,” Moes and Tellinghuisen continue, “scientists, Christians, and Christians who are scientists, are living in a broken world. This means that humans can make errors in doing and interpreting science, as well as in their interpretations of scriptures.” When faced with apparent contradictions, in addition to examining the research methods and assumptions of the offending research, we should also explore whether our religious assumptions should be re-examined.

Intellectual humility is the antidote to both scientism and fundamentalism.

Intellectual humility entails a third path between (and apart from) the extremes of both scientism and fundamentalism, and it is key to becoming a disciple-scholar. With respect to scientism, intellectual humility involves recognizing the limits of rational and empirical methods, avoiding excesses and dogmas of scientism, and acknowledging our dependence on God for divine wisdom. With respect to fundamentalism, intellectual humility involves recognizing that (by divine design) all revelation entails human actors who bring their own personalities and biases to the table—and that high-quality empirical research can be a vital resource. In this way, intellectual humility is a contrast to the subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) arrogance undergirding both scientism and fundamentalism.

Let us look at an example: If scientists claim that the earth appears to be billions of years old, fundamentalists will reject this because they (mistakenly) believe that a literal interpretation of the Bible requires us to believe that the earth is much younger than that. However, faithful Latter-day Saint scholars have argued that the Old Testament was never intended to be a science textbook—its purpose is to teach us about our relationship with God as our Creator. It doesn’t require us to believe anything in particular about how God created the earth, or even how long it took. As Galileo once quipped: “The intention of the Holy Spirit is to teach how one goes to heaven, not how the heavens go.”

By contrast, if prophets teach that God was involved in the creation of the earth, those who embrace scientism might reject this because it cannot be empirically verified by the naturalistic methods of science. Indeed, they might argue that science has definitively demonstrated that life arose through spontaneous and unguided processes, without the involvement of any Divine Being. However, this goes far beyond what science can actually claim or prove. Scientific methods can help us detect patterns in the natural world (and in human experience), but they cannot tell us anything about whether there is or is not a Divine Being who is responsible for creation and to whom we are accountable. Both groups are making assumptions they do not recognize as assumptions.

Let’s look at an additional example from psychology to demonstrate further. In 2014, John Dehlin and his colleagues published a study on the experiences and outcomes of 1,612 same-sex attracted former and current members of the Church. One of the questions asked in the study was, “What are the mental health implications of both religious disaffiliation and entering into committed same-sex relationships for LGBT+ individuals?” In the study, they conclude that affiliating with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints led to poorer mental health outcomes for LGBT+ populations (note, this conclusion is contested in other research). In their conclusion, they state:

Those who are in a position to provide counseling to conservatively religious LGBT+ individuals … should consider … disaffiliation from non-LGBT+-affirming churches, and legal, same-sex committed relationships for LGBT+ religious individuals.

This conclusion is a fundamentally moral assertion, and yet it is presented as if it were the only and obvious implication of the empirical evidence. By not articulating or examining their assumptions, the authors imply that their conclusions are simply the products of a strictly empirical examination (“just the facts”). This is why we argue that their article is a great example of scientism in action. The authors leave unstated and unexamined a host of philosophical assumptions and moral worldviews that influence the questions they investigated, the methods they used, and their interpretations of the results.

For example, their research questions were not asked in a vacuum, but in the context of ongoing ideological and philosophical tensions between religious and secular views of same-sex attraction and behavior. The singular look at the mental health outcomes of LGBT+ individuals —rather than including spiritual outcomes in their array of measures of personal well-being— reveals hidden assumptions about the nature of human flourishing. It was neither interesting nor important to the authors that LGBT+ individuals who disaffiliated with the Church continued in spiritual devotion or still found themselves believing in or connected to God —which is an expression of values and priorities that are fundamentally pre-empirical.

In short, their research questions—what they looked at (and thus, what they saw)—were influenced by their prior moral and philosophical biases (such as expressive individualism, which we will explore more later in this book). And the way they interpreted the evidence was informed by the same worldviews. From the exact same empirical evidence (but from a different starting point), they could have just as easily suggested the need for more institutional support from the Church for single and celibate members, or better mental health resources and more spiritual help for those striving to live the law of chastity under unique circumstances.

While the pre-empirical assumptions of the above study are easy to identify (this was an egregious example), the assumptions of other psychological research are often more subtle and harder to detect—but they nonetheless always exist. Of course, the answer is not to lean more towards a fundamentalist approach. A fundamentalist approach might reject the need for any social scientific research into this topic at all, or rely solely upon tradition to understand the needs of LGBT+ individuals within the Church. In contrast, we suggest that a better path forward is to embrace intellectual humility.

Intellectual humility involves a willingness to articulate and interrogate the otherwise hidden assumptions behind both our religious traditions and our scientific explorations—and to do so using the light of both revealed truth and careful research. This helps us thread the needle between fundamentalism and scientism, and we think it is one of the paramount virtues of being a disciple-scholar. Intellectual humility (within the context of a Latter-day Saint perspective) involves respecting both the ecclesiastical authority of prophets and apostles and the epistemological authority of scholars and scientists (in the right contexts).

Note: intellectual humility does not in any way foreclose conviction. Some writers describe intellectual humility as a lingering “tentativeness” in all of our perspectives, but that is not how we use the term. As psychologist Justin L. Barrett puts it, intellectual humility reflects “a tendency to accurately track whether or not one should hold certain beliefs to be knowledge: not overconfident in one’s beliefs, but also not holding them too loosely when one should hold them firmly.”

In short, intellectual humility means that we acknowledge our assumptions as assumptions. Gaede argues that a genuinely Christian approach to the social sciences will eschew all forms of dogmatism. He explains:

[A Christian social science] assumes that science will best be served by a genuine pluralism that allows all scientists to build freely upon their chosen assumptions. Unlike [scientistic approaches], which argue that every scientist must conform to its assumptions to assure impartiality, a Christian social science assumes that scientific integrity will be best served by philosophical candor and a clear explanation of assumptions.

We, for example, have a deep and unmoving conviction that human beings are moral agents (this is not something we take as tentative or provisional), and in subsequent chapters, we will assert that this should be a guiding assumption of all of our research. Intellectual humility does not require us to constantly question that assumption—it simply requires that we acknowledge this as a pre-empirical assumption and a philosophical commitment, and thus open to critical analysis and reflection, rather than an indubitable fact handed to us by empirical evidence. Further, as Gaede explains, this “philosophical candor” means that “authors should not play cat and mouse games with their readers, disguising presuppositions in the vain hope of producing value-free science.”

And lastly, intellectual humility means (for Christians and Latter-day Saints) recognizing the inherent incompleteness of any mortal attempt to get at the fundamental truths of the universe. It involves recognizing, as Gaede explains, “that we are not God and we will not, as finite beings, ever attain an understanding as complete or total as His”—at least, in this life. This is where we depart from Gaede, as unique Latter-day Saint doctrines do not posit the same unbridgeable, metaphysical gulf between God and man. Unlike Gaede, we believe that this metaphysical and epistemological gulf can and will be bridged as we eventually step into the full stature of our station as joint-heirs with Christ. These differences do not affect Gaede’s ultimate point, however—a point on which we strongly agree. Gaede continues:

In a sense, while we are to pursue truth with all our strength, we are never to forget that God is the author of truth and that we are dependent upon Him for our understanding and knowledge. Once again, this beckons the scientist to a posture of humility regarding any truth claims made on the basis of scientific research. I might add parenthetically that it calls the theologian and all other human sojourners to precisely the same position.

Intellectual humility helps protect us from the pride that so often accompanies scholarly pursuits. The prophet Jacob warned, “When they are learned they think they are wise, and they hearken not unto the counsel of God, for they set it aside, supposing they know of themselves … But to be learned is good if they hearken unto the counsels of God.” With the sort of humility that places God’s wisdom before our own, we can pursue discipleship in a way that avoids the pitfalls described by Jacob. Elder Neal A. Maxwell wrote, “Though I have spoken of the disciple-scholar, in the end, all the hyphenated words come off. We are finally disciples—men and women of Christ.”

______________________________________________________________

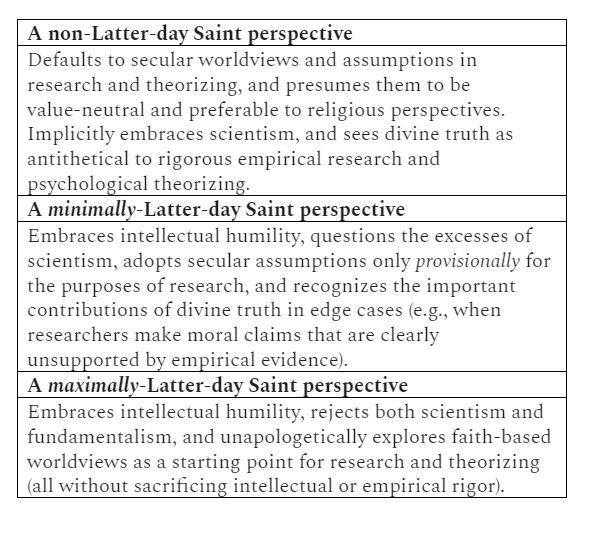

The purpose of this project is not to set forth a definitive or authoritative Latter-day Saint perspective in psychology. Instead, we would argue that there are many different perspectives and directions to go, even while taking seriously the thirteen “foundations” we set forth in this project. With each chapter, we will identify what we consider to be the minimal and maximal approaches to embracing these foundations.

The post Encouraging Disciple-Scholars in the Social Sciences appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →